View

A Vocabulary for Worship

Dan Sheffler on Taking Seriously Gravitas, Dignitas & Pietas

If any people in history knew it, the Romans knew how to be serious about serious things. Next to the cultured poets and philosophers of Athens, the Romans saw themselves as a race of soldiers and farmers. The religious rites that Numa instituted early in Rome’s history cultivated a deep reverence for ancestry and custom, for bonds between neighbors, and for those boundaries that designate and hallow sacred ground. Roman law reflected a concern for those spaces that must not be violated, whether they be in a temple, a city, a house, or a man’s soul. This gravity, admittedly, came along with an almost unbelievable degree of cruelty, and when the Romans did violate that which they knew to be sacred, they were capable of a kind of blasphemy that Anton LaVey only childishly imitates.

As Rome turned to the light of the gospel, however, that old Roman spirit with its old Roman language bequeathed to the rising Christian civilization a vocabulary of religion. Indeed, the word religio can scarcely be translated anymore, because what it signified to the Latin mind—a whole nexus of ritual and feeling that binds a community together—will strike modern secular society as nothing but a silly costume party. Today’s society knows how to be flippant about serious things, but where it sees its flippancy as characteristic of enlightenment, its Roman forebears would have seen it as characteristic of barbarism.

Listen, for example, to the disdain and hatred with which Livy describes the impiety of Hannibal—right after he praises the general’s martial virtues:

Has tantas viri virtutes ingentia vitia aequabant: inhumana crudelitas, perfidia plus quam Punica, nihil veri, nihil sancti, nullus deum metus, nullum ius iurandum, nulla religio.

But these great merits were matched by great vices—inhuman cruelty, a perfidy worse than Punic, an utter absence of truthfulness, reverence, fear of the gods, respect for oaths, sense of religion. (Ab Urbe Condita 21.4, trans. Benjamin Oliver Foster)

The modern, urbane, secular man has become just such a person, only without the martial virtues. His limp-wristed relativism contains no sense of truth (nihil veri); his scoffing attitude holds nothing sacred (nihil sancti); his foul mouth and moral carelessness betray nothing of that fear which is the beginning of wisdom (nullus deum metus); his three divorces demonstrate an utter disregard for oath and covenant (nullum ius iurandum); and of course, forty years have gone by since he last went to church (nulla religio).

Coat-hooks for Ideas

Classical schools do many things at once to combat this slide into degeneracy; thus, the classical school movement represents one major point of hope for the future. At these schools, children will of course learn Latin, and as they dutifully drill their flashcards and painstakingly translate passages from Cicero and Virgil, they will encounter a whole array of words that cannot easily be translated into the language of flippancy.

So, at one level, simply learning Latin vocabulary will do them good, because a word acts like a designated coat-hook in the mind, on which they can hang ideas. Without the hook, the ideas tend to flop down into a sloppy pile—in the mind but indistinct.

At a deeper level, however, struggling to translate these words in the context of classical culture will bring students into a world of thought with an altogether different tenor from their own. Three words in particular capture the Roman spirit well and prove helpfully tricky for students to translate: gravitas, dignitas, and pietas. Like such students, and like those Roman Christians who converted the language of an empire into a language for the kingdom of God, Christians today can renew their vocabulary of worship through reflection on these words.

•Gravitas

Gravitas originally comes from the adjective gravis, which in its most literal sense means “heavy.” The Romans extended this original, physical sense of weight into the psychological and spiritual realms, so that gravis came to mean “serious,” “important,” or, when English picked it up, “grave.” Gravitas thus denotes the presence of weightiness in something or someone; it conveys an aura of momentousness, which surrounds things that matter. Gravitas is the quality that makes things sink decisively in the scales, and its opposite is all that is trivial or frivolous, what someone might today call “fluff.”

The Romans knew as well as we that this weightiness could have its negative, even comic, side, and frequently when they spoke of someone’s gravitas, they meant that he was harsh or self-important. The error and comedy come in, however, not because everything deserves to be treated with casual wit but because some old Roman men were so habituated to the posture and tone of weightiness that they carried their expressions inflexibly into contexts that warranted a smile.

Although he wrote in Greek rather than Latin, the Apostle Paul likewise felt the natural connection between weightiness and that which matters when he wrote, “For our light affliction, which is but for a moment, worketh for us a far more exceeding and eternal weight of glory (baros doxes)” (2 Cor. 4:17). Paul likely made this connection because he had in mind the Hebrew word for glory (kabod), which comes from a root signifying heaviness. C. S. Lewis used Paul’s phrase as the title of his justly famous sermon, “The Weight of Glory,” whose magisterial final paragraph connects the idea of weightiness to that of a burden: “The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbor’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken.”

Here one finds the fully Christian conversion of that Roman gravitas which tends so easily toward stony-faced self-importance. The Christian does not seek to locate the heaviness of import in himself but in his neighbor. This neighbor may be counted insignificant by the world, but the Christian knows what truly carries weight: that the man before him is a person made in the image of God, a person for whom Christ died.

• Dignitas

Dignitas comes from the adjective dignus, which means “worthy.” Like gravitas, it signifies the presence of an intangible quality conveying a sense of great value. From the columns of their temples to the pomp of their triumphal processions, the Romans sought to bestow grandeur, majesty, authority, and eminence upon their empire. As with gravitas, the quality of dignitas can, of course, be misapplied and become a vice. The Romans exalted much that should be despised, and an emperor such as Nero became the very picture of insane human pride. The answer to this sin, however, is not to become casual about everything but rather to reserve dignitas for that which deserves it, for that which is truly worthy.

Modern culture may know abstractly that something is worthy, but it preserves few institutions or practices that seek to surround these worthy things with the sense of their worth. Instead, it surrounds marriage with the sentimentality of Hallmark, and it surrounds fictional heroes with enough explosions and dramatic music to make them feel “epic.” Worst of all, I fear that these sentiments have come to dominate the aesthetics in our churches as well. At its best, Christian worship has always been able to incorporate these easier feelings where they were appropriate while keeping the gaze of the saints firmly fixed in serious wonder at a worthy God.

Perhaps this age’s inability to dress what is worthy in royal robes comes from its democratic impulses and its repugnance at the pretensions of monarchy. Admittedly, former ages have erred toward a ridiculous pomposity and have dressed arrogance and imbecility in aristocratic finery. In cases of such folly, mockery may be in order lest the rich young ruler take himself too seriously and lest he forget the poor. The democratic impulse is to bring such men down a few pegs and teach them to dress, talk, and carry themselves like everyone else. The hope is that, if the proud are brought down, everyone else will be raised up to the dignity of universal brotherhood.

But bringing everything down to the aesthetic of the common man does not ennoble the poor, as innumerable strip malls, gas stations, and slums will readily attest. Rather, it is Christ who ennobles the poor man, by freely inviting him to the King’s banquet. Such an invitation teaches a man to stand up straight, to lift his chin, and to walk like a man and not like a beast—to walk, in other words, with dignitas.

• Pietas

Pietas takes us even farther than gravitas and dignitas from the familiar world of contemporary life—and even from much contemporary religious life—because pietas combines into a single sensibility the domains of worship, family loyalty, and patriotism. Or better (as Owen Barfield would no doubt remind us): pietas signifies what was once a single unified feeling, which successive generations have broken apart into separate pieces through the inevitable analytic processes of language.

This feeling lives within a man as a trembling awareness of those claims placed upon his life by God, by his family, by his clan, and by his native soil—claims that require responsibility and sacrifice, and perhaps even martyrdom. On the one hand, this awareness contains a note of dread because it is an awareness of duty that a man must attend to all the way to death. On the other hand, however, this awareness brings a deep joy because it roots a man in those bonds that make possible a fully human life.

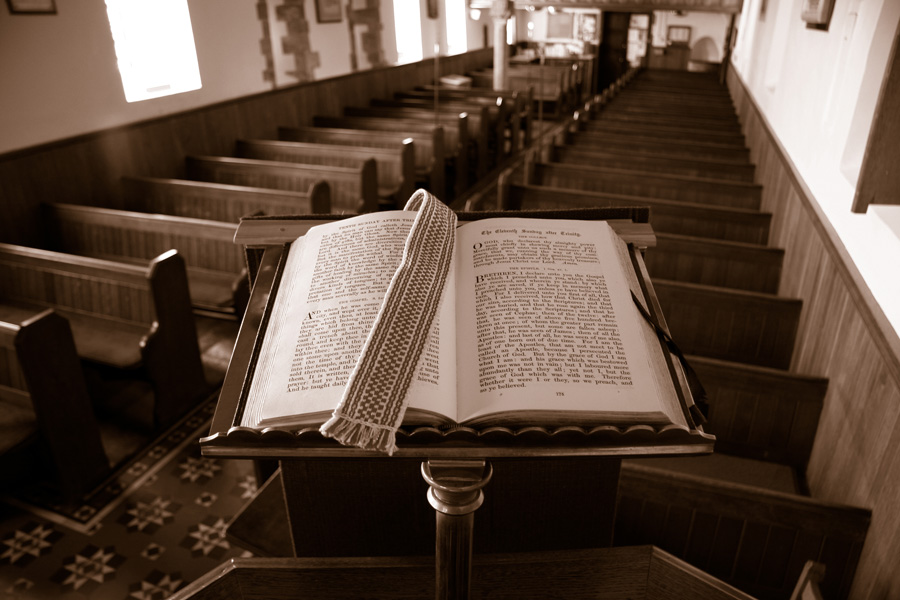

People nowadays tend to restrict “piety” to the religious sphere, and even in Latin the religious aspect remains always at the forefront. (The root, piare means “to atone for” or “to purify through sacred rites.”) Understanding the complexity of pietas, however, helps the Latin student to see that the proper religious attitude is connected to the proper attitude toward other spheres of life. The disposition that evokes an attitude of hushed reverence when one enters a church sanctuary is the same disposition that teaches him to feel the thunderclap of irrevocable commitment when he makes his marriage vows or to sense the sober shroud of honor cast over Arlington National Cemetery. I wonder how a Roman would have regarded the modern fad of placing cute cafés in the crypts of churches like St. Paul’s or St. Martin-in-the-Fields.

Getting Serious

One will readily notice that these three words have to do with feelings. Gravitas and dignitas apply to the object of feeling, while pietas applies to the subject. They all, however, turn one’s attention toward the affective dimension of experience and away from the cognitive.

In our day, it sometimes seems as if those serious about their faith have turned almost entirely toward the life of the mind and thereby left the affective aspects of worship to the most frivolous tastes. More likely, the slow acids of an increasingly mass culture have eaten away at the modern worshiper’s very capacity for deeper feeling. This seems especially to be the case in large, trendy Evangelical churches, but whole swathes of the Catholic landscape seem to be infected with the same malady. One should not think, therefore, that the issue boils down to Reformation disputes about the place of art in the churches or the celibacy of the priesthood. Indeed, some country Pentecostals seem to know the awful presence best of all.

Whatever the cause of our malady, the path to recovery lies through books—old books, in dead languages. But of course, the Romans themselves might simply suggest a vigorous, manly effort toward the serious treatment of serious things.

Dan Sheffler (Ph.D., University of Kentucky) teaches philosophy at Georgetown College in Kentucky. With his wife and three children, he is a member of Lexington Christian Fellowship.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

8.4—Fall 1995

The Demise of Biblical Preaching

Distortions of the Gospel and its Recovery by Donald G. Bloesch

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor