View

Young Adult Friction

Kristine Wallace Palmer on Novel Superheroes versus the Human Adventure

My daughter is a reading omnivore. A typical 13-year-old, she is old enough to have free rein in the library, but too young to have developed actual taste. She reads science encyclopedias, Westerns, joke books, parenting manuals, classics like

A Tale of Two Cities, and, of course, young adult novels.

The only part of this joyfully haphazard program that I do not recognize from my own childhood is the young adult novel. These have changed significantly since the 1980s and 1990s. Never fear, there is a still a "YA" section in the local library, and it is still populated by musty beanbag chairs and paperbacks with cheesy cover art. Some of what's behind those covers is still familiar, too. The Fault in Our Stars, one of the best-selling YA books of the last decade, is about two teenagers who fall in love, both of whom have cancer. That particular theme—doomed romance—has been well-represented in teen literature down through the ages.

A new genre has popped up in the YA category, however. Like an invasive species, it is slowly taking over shelf space from the domestic melodramas, coming-of-age tales, and classic adventure stories that used to predominate. I'm going to call this new genre the superhero adventure story.

Super, but Not Interesting

In the superhero adventure story, the hero or heroine does not want to grow up, leave home, fall in love, or explore any part of the universe whatsoever. Apparently authors think that the wanderlust that characterized the young protagonist of yesterday would feel inauthentic to the teen of today. Frequently, then, the plot is constructed so as to compel the hero to leave home. The fate of the world, it is explained, hangs in the balance.

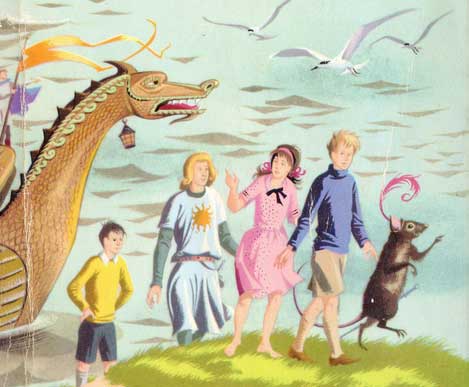

Often this is laid on absurdly thick. Consider the 1952 classic adventure novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. In C. S. Lewis's original novel, Caspian sets sail on a "glorious venture"—that is, for the sheer fun of it, and also to fulfill a vow he made to find the lost Lords of Narnia. He is not trying to save Narnia from any sort of peril. "You don't suppose I'd have left my kingdom and put to sea unless all was well," he says.

Tastes have changed. In the 2010 Walden Media film version, the child protagonists must defeat a sinister green mist. The mist "seeks to corrupt all goodness" and "steal the light from this world."

Having established the existential threat, the recipe calls for the hero to make one last-ditch effort to stay safely cocooned at home. "Why must I be the one to go?" he asks, in tones reminiscent of my ten-year-old's when he asks why he must be the one to sweep the kitchen floor. The answer is that the hero must go because he is in some way singular, super, or "chosen." The reluctant champ-ion—the Achilles model—is the quintessential superhero protagonist.

Achilles' fate is marked out from birth. He is "the chosen one"—or is that Harry Potter? Percy Jackson, hero of the best-selling The Lightning Thief, turns out to be a demi-god. Tris Prior, heroine of the popular Divergent series, is "divergent" from other people and immune to mind-control serum. Mare Barrow, heroine of the smash hit Red Queen, has special blood running through her veins. So does Clary Fray, heroine of The Mortal Instruments books, movie, television show, and graphic novel. Her special blood makes her half angel, which is way better than being a mere "mundane," i.e., a regular, non-special-blood person. Better, maybe, but not more interesting.

When your very blood is special, everyone sees right away where your story is going.

Stories with Real Surprise

American short-story writer O. Henry (1862–1910) created no superhero characters and told of no save-the-world quests. Yet he was a master at achieving the very thing contemporary superhero adventure books lack entirely—real surprise. In "The Green Door," he let slip his secret. "The true adventurer," he wrote, "goes forth aimless and uncalculating to meet and greet an unknown fate. A fine example was the Prodigal Son—when he started back home."

The Prodigal Son really is the ultimate adventurer. He does not want to save the world, only his own skin. He travels from a far country not knowing what end awaits him. When the end does come, it comes as a genuine surprise.

And he is the younger brother. This is an important point in itself. The true adventurer is generally not chosen or fated, because in general he is not special. He is not the heir to the throne or even to the family farm. He is frequently below average, not clever, and not marked out for greatness. His blood is disappointingly ordinary.

Take Gawain. In Tolkien's translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Gawain appeals to be allowed to take a dangerous adventure on the basis of his own insignificance: "I am the weakest, I am aware, and in wit feeblest, and the least loss, if I live not." He subsequently has "one of the wildest adventures in the wonders of Arthur."

Far from being special, the hero of a classic adventure story is in fact especially normal. That is, he is especially attuned to the norms of human behavior. (The norm Gawain is especially attuned to is courtesy.) G. K. Chesterton said that in all fairy tales—he might as well have said adventure stories—"it is assumed that the young man setting out on his travels will have all substantial truths in him; that he will be brave, full of faith, reasonable, that he will respect his parents, keep his word, rescue one kind of people, defy another kind, 'parcere subjectis et debellare [superbos]' [spare the vanquished and subdue the

proud], etc."

Indeed, it is often the hero's making the proper response to whatever befalls him that brings an adventure story to its surprising-but-satisfying ending. He is kind to the old crone. He follows directions to the letter. He does not let curiosity get the better of him. He tells the truth. In short, he observes all the conventional rules of behavior one might emphasize to a six-year-old. He attains the extraordinary through rigorous adherence to the

ordinary.

Learning (or Not) to be Normal

One of the classic purposes of literature is to teach all young people to do likewise. C. S. Lewis thought that literature of this type was undervalued in his day, with potentially disastrous results. An ongoing refrain in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is that what the other children experience as adventure, Eustace experiences as misery. Eustace hasn't read the right books. Consequently, he's constantly doing the wrong thing, and it makes him wretched and unpleasant to be around. Eustace is C. S. Lewis's picture of a young person who has never learned to be a normal human.

"The elementary rectitude of human response," Lewis wrote in his Preface to Paradise Lost, "at which we are so ready to fling the unkind epithets of 'stock,' 'crude,' 'bourgeois,' and 'conventional,' so far from being 'given' is a delicate balance of trained habits, laboriously acquired and easily lost, on the maintenance of which depend both our virtues and our pleasures and even, perhaps, the survival of the species."

It is almost as if America has been running an experiment to test his theory. Let's say that a woman has just written a novel and is about to read a review of it in, say, the New York Review of Books. What is she hoping the reviewers will say? If they call her novel "transgressive," they will have praised it as extensively as she could have wished. She will have succeeded in making her characters avoid all of the "stock responses" that Lewis says are indispensable for human thriving. She'll be able to breathe a sigh of relief and take her place among the smug secular saints who make up the modern literati. Perhaps Christian schools will teach her transgressive book in their literature classes to prove to themselves that they are not stodgy—er, that is, to "foster critical thinking."

Meanwhile, fewer and fewer young people are getting an education in those age-old "stock responses" that prepare them for adventure. This is a pretty big problem because embarking on adult life really is like going forth "to meet and greet an unknown fate."

My husband is a campus pastor at a big state university, and he meets quite a few young people who simply haven't developed a taste for that kind of risk. When he advises students in dating relationships, he frequently suggests that they, ahem, get married. "We aren't ready for that," they say. Never mind that they are two ostensibly mature 22-year-olds. Marriage . . . children . . . these are wild leaps, really tremendous undertakings, for people who don't know they are supposed to be easy and natural.

My husband's students are not unique. Jean Twenge, the author of iGen, a book reporting social science findings about the generation following the Millennials, writes, "Fewer young adults are having sex, fewer are in committed relationships, and fewer prioritize marriage and family." Young adults are "increasingly disconnected from human relationships—except perhaps with their parents."

Lewis's claim that an education in the "stock responses" of being human is necessary "for the survival of the species" doesn't seem overstated in the light of these data.

Young adult books, superhero movie franchises, graphic novels, and public school slogans all combine to create a diabolical cultural catechism, a sort of humanity-crushing educational juggernaut. Their mono-voice says that young people are not supposed to cherish or nurture the merely human. Rather, their onerous job throughout their teens and twenties is to find within themselves unique abilities and passions they can use to positively influence the world. They are supposed to be superheroes, just like the protagonists of all the books they read. If a young person hasn't yet hit on the superhero within, it would be morally wrong for him to devote himself to anything else until he's dug a little deeper and tried a little harder to find it. Until then, to make any commitment that detracts from the project of super self-actualization is a tainted compromise. For example, saying "I love you" to another person is only for the weak of heart.

One twenty-year-old man quoted in iGen has totally absorbed this message and strives to live up to it. "I just feel like that period from twenty to twenty-five is such a learning experience in and of itself. It's difficult to try to learn about yourself when you're with someone else," he says.

Old-fashioned adventure stories often end with a boy and a girl in a fair way to being married. The reader trusts that the wedding will take place and that a year later the newlyweds will welcome a cherry-cheeked baby. But that natural conclusion doesn't really come naturally. It is the result of careful training in being human. Absent such training, normal impulses may never assert themselves and come to fruition.

Reading & Writing the Right Books

As must be clear by now, I think the problem is that young people just haven't read the right books. I'm not talking about Literature with a capital L. I was an English major myself, and I like Shakespeare significantly more than the next person, but I can acknowledge that the stock responses of being human can be taught just as well by pulp fiction—maybe better, insomuch as the norms of human behavior are, by definition, for all human beings and not just for book nerds.

Someone reading this ought to write a better young adult novel. The demographic (and thus economic, political, even religious) future of America might depend on it.

Kristine Wallace Palmer is a homemaker and the mother of nine. She and her family attend Catalina Lutheran Church in Tucson, Arizona, where her husband is assistant pastor and chaplain for the University of Arizona.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

27.3—May/June 2014

Religious Freedom & Why It Matters

Working in the Spirit of John Leland by Robert P. George

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor