2017 Conference Talk

The Garland of Immortality

A Theology of Martyrdom in the Early Church

by Bryan A. Stewart

Around the year a.d. 155, the 86-year-old bishop of Smyrna, named Polycarp, was arrested by Roman authorities. The charge leveled against him was that he was a Christian. On his way to the arena, some individuals tried to persuade the aged Polycarp to save his life by recanting his faith and making sacrifice to the pagan gods. “What harm is there,” the police captain argued, “for you to say, ‘Caesar is Lord,’ to perform the sacrifices . . . and thus save your life?” Polycarp refused.

Later, having arrived in the arena, the proconsul took a different approach to persuade the bishop to recant. “Have respect for your age,” he argued; “swear by the genius [spirit] of Caesar and recant. . . . Swear [the oath of allegiance] and I will let you go. Curse Christ!” Again, Polycarp refused, this time with the famous words, “For eighty-six years I have been his servant, and he has done me no wrong. How can I blaspheme my King who saved me?” Polycarp would stand upon the simple, but clear, confession: “I am a Christian.”

That trial ended with Polycarp being first burned and then stabbed to death before a crowd of onlookers. The document that recounts his death, The Martyrdom of Polycarp (hereafter MP, contained in The Acts of the Christian Martyrs [hereafter ACM], ed. Herbert Musurillo [Clarendon Press, 1972]), is one of the earliest martyrdom accounts we have from the first three centuries of the Church. It would by no means be the last. Because of their consistent refusal to offer pagan sacrifice—an act Christians understood as idolatry—thousands of Christians in the Roman Empire would come to know the fate of Polycarp only too well. Until the peace of Constantine in the early fourth century, arrest, mistreatment, persecution, and execution for being a Christian was a true possibility, and many thousands would come to know it as a reality. This was, in the words of scholar William H. C. Frend, “the heroic age of the church” (Martyrdom and Persecution in the Early Church [New York Univ. Press, 1967], ix).

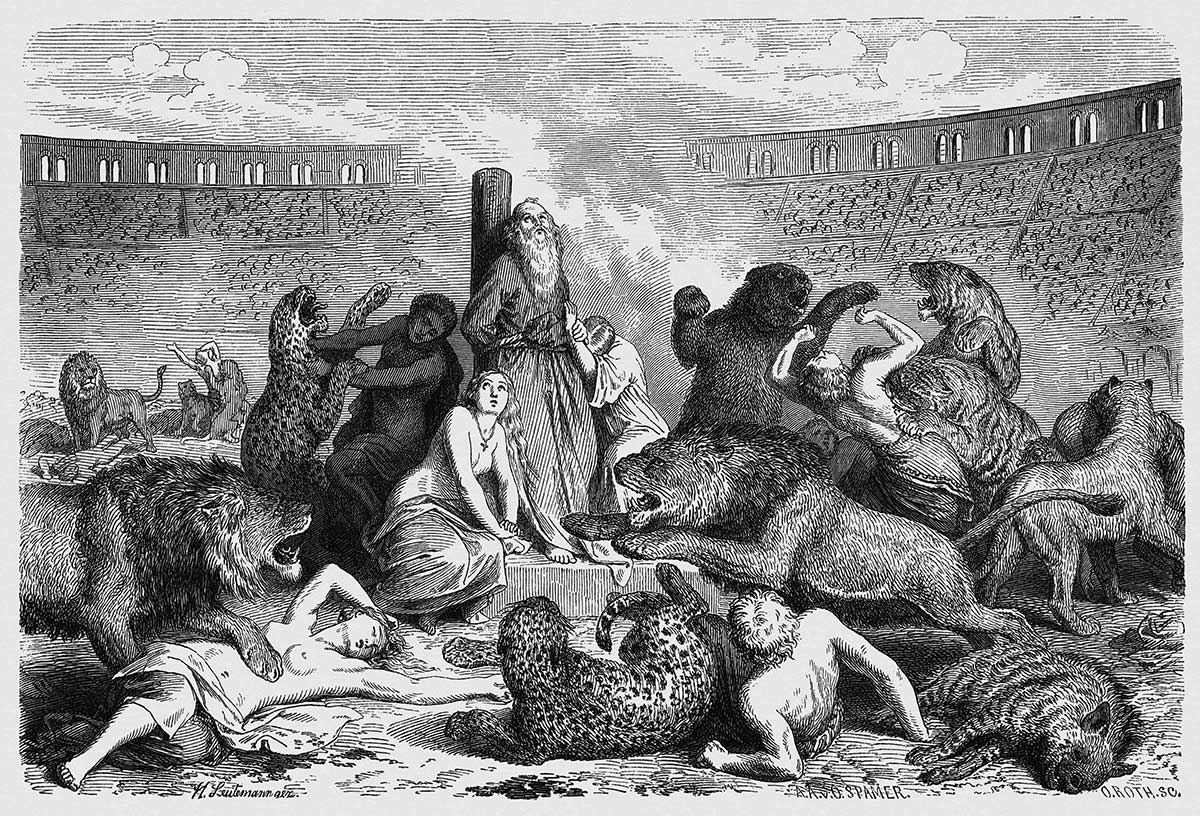

These persecutions gave rise to a new kind of Christian literature: trial records and passion narratives recounting the episodes of persecution. Such documents often contained graphic details of the cruelties and tortures Christians endured at the harsh hands of Roman soldiers and magistrates, which included being burned alive, stabbed, and thrown to wild beasts to be torn apart by tooth and claw. Eusebius of Caesarea, a fourth-century bishop and historian, describes Christians being subjected to hot iron placed on sensitive parts of their bodies, boiling water and molten lead being poured upon their naked flesh, their limbs being ripped apart, and their skin being flayed with sharp instruments of clay and metal (Eusebius, Church History VIII.9, 12).

The early Christian martyrdom accounts are no sweet bedtime stories. Yet for all their gruesome details, we know that they were intended to give encouragement and inspiration to living Christians; indeed, they were often circulated among churches and read aloud in public liturgies. Moreover, these Christian deaths were considered to be nothing short of—in the words of the account of Polycarp—“martyrdoms in accord with the pattern of the gospel of Christ” (MP 19.1).

What, we might ask, did it mean for Christians of the time to write and circulate records of the trials, persecution, and (often brutal) deaths of their fellow brothers and sisters, and in what way did they consider them to be “in accord with the pattern of the gospel”? Or, to put the question more simply: What was the theology of martyrdom in the early Church?

We might begin to answer that question by looking into what the word “martyr” means. Ask people today and most of them will say something like: “A martyr is someone who dies for his faith or who is killed for what he believes in.” While this is true, of course, of the early Christian martyrs, it does not capture the full meaning of the ancient texts, because it leaves out the original meaning of the Greek word martyr, which is “witness.”

When early Christians reflected on the deaths of their fellow believers at the hands of the Romans, and when they began to write about them, the word they intentionally (and consistently) chose for them was martyr, “witness.” In their deaths, these Christians became witnesses to other believers and to the world; in particular, they became “witnesses” of the pattern of the gospel itself. I would like to highlight four distinct yet related aspects of the theology of martyrdom as “witness” in the early Church.

A Spiritual Battle

First, martyrdom was understood as witnessing to the real spiritual and cosmic battle taking place in the hidden realms. Early Christian literature repeatedly refers to Christian martyrs as “noble athletes” who are fighting, not against Roman soldiers or wild beasts, but against the dark forces of Satan. This theme of spiritual battle is not subtle. One account describes a martyrdom in second-century Gaul as “the Adversary swooping down with full force” (The Martyrs of Lyons [hereafter ML] 1.5, in ACM). A third-century text from North Africa explains that “the onslaughts of persecution surged like the waves of this world, and the fury of the ravening Devil gaped with hungry jaws to weaken the faith of the just” (The Martyrdom of Saints Marian and James 2, in ACM).

The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity is perhaps the most vivid and elaborate depiction of martyrdom as a spiritual battle against Satan. It took place in a.d. 203 in North Africa. Perpetua, a 22-year-old noblewoman, new mother, and Christian, had been arrested, along with four others, for her faith. While in prison awaiting her fate, Perpetua kept a diary, and several lengthy excerpts from it are included in the account of her martyrdom. In one of these excerpts, Perpetua describes a vision she had about her impending death:

I saw a ladder of tremendous height made of bronze, reaching all the way to the heavens, but it was so narrow that only one person could climb up at a time. To the sides of the ladder were attached all sorts of metal weapons: there were swords, spears, hooks, daggers, and spikes; so that if anyone tried to climb up carelessly or without paying attention, he would be mangled and his flesh would adhere to the weapons.

At the foot of the ladder lay a dragon of enormous size, and it would attack those who tried to climb up and try to terrify them from doing so.

Saturus was the first to go up. . . . He arrived at the top of the staircase and he looked back and said to me: “Perpetua, I am waiting for you. But take care; do not let the dragon bite you.”

“He will not harm me,” I said, “in the name of Christ Jesus.”

Slowly, as though he were afraid of me, the dragon stuck his head out from underneath the ladder. Then, using it as my first step, I trod upon his head and went up. (The Martyrdom of Saints Perpetua and Felicity [hereafter MPF] 4, in ACM)

The meaning of the vision is clear enough. Martyrdom is a kind of battle that involves running the gauntlet of a variety of weapons of death. But the most formidable opponent is the dragon lying in wait at the foot of the ladder. Drawing on imagery from Revelation 12, where Satan is depicted as a dragon, Perpetua sees that she needs to face and defeat this evil force if she is to ascend through martyrdom to heaven. In the vision, she succeeds by using the head of the dragon as her first step, thus echoing the promise of Genesis 3:15: that one day the Messianic offspring of Eve would come to crush the head of the serpent. Just as Christ conquered the power of the devil through his death and Resurrection, so, too, Perpetua must fight a spiritual battle against the devil before gaining the victory.

Later, Perpetua had another vision in which she faced a mighty Egyptian gladiator. After joining in battle with him for a time, she managed to force the Egyptian’s face to the ground and then stepped on his head. The Egyptian symbolized a dark spiritual force, for upon waking from her vision, Perpetua declared: “I realized that it was not with wild animals that I would fight but with the Devil” (MPF 10).

For early Christians, martyrdom was, as Robin Darling Young puts it, nothing short of a “public liturgy of combat” (In Procession Before the World: Martyrdom as Public Liturgy in Early Christianity [Marquette Univ. Press, 2001],9). Indeed, drawing on the language of Paul in 1 Corinthians 4:9, early Christians saw martyrdom as a “spectacle (théatron) to the world, to angels, and to humankind.” Those who observed martyrs being led to their deaths were in fact witnessing a spiritual battle between the forces of Satan and those who belonged to Christ. It was the ultimate battle, and the onlookers included more than the frenzied crowds in the arena. As Origen of Alexandria wrote in the third century, the entire cosmic order stood in attendance at every martyrdom:

The whole world and all the angels of the right and the left, and all men, those from God’s portion and those from the other portions, will attend to us when we contest for Christianity. Indeed, either the angels in heaven will cheer us on, and the floods will clap their hands together, and the mountains will leap for joy . . . or, may it not happen, the powers from below, which rejoice in evil, will cheer. (Exhortation to Martyrdom [hereafter EM] 18, in Origen: An Exhortation to Martyrdom, Prayer and Selected Works, trans. Rowan A. Greer [Paulist Press, 1979], 53–54)

Either way, behind the physical experience of swords, fire, and wild beasts, there lay a spiritual reality, seen only by those who truly understood what was happening. For early Christians, martyrdom gave witness to this spiritual battle.

Reward & Joy

Of course, spiritual battle brings with it the hope and promise of a reward for persevering. This is the second prominent aspect of the theology of martyrdom. In Perpetua’s vision of the ladder, the reward for completing the ascent was reaching heaven, and in her diary she continues that theme by describing her vision after reaching the top:

Then I saw an immense garden, and in it a grey-haired man sat in shepherd’s garb; tall he was, and milking sheep. And standing around him were many thousand people clad in white garments. He raised his head, looked at me, and said, “I am glad you have come, my child!” He called me over to him and gave me, as it were, a mouthful of the milk he was drawing; and I took it in my cupped hand and consumed it. And all those who stood around said: “Amen!” At the sound of this word I came awake, with the taste of something sweet still in my mouth. (MPF 12)

Later, according to the same Passion narrative, Saturus, a companion of Perpetua, had a similar vision, in which he and others, having died in martyrdom, were carried by angels to heaven. Saturus writes: “A great open space appeared which seemed to be a garden, with rose bushes and all manner of flowers.” Then, in a depiction clearly evoking the heavenly scene of Revelation, he sees another angel bidding them to come and meet the Lord:

Then we came to a place whose walls seemed to be constructed of light. We also entered and we heard the sound of voices in unison chanting endlessly: “Holy, holy, holy!” In the same place we seemed to see an aged man with white hair and a youthful face, though we did not see his feet. On his right and left were four elders, and behind them stood other aged men. Surprised, we entered and stood before a throne: four angels lifted us up and we kissed the aged man and he touched our faces with his hand.

The scene ends with the declaration, “Thanks be to God that I am happier here now than I was in the flesh” (MPF 12).

For early Christians, death in martyrdom was not the end, but was a gateway to something far greater, variously described as an “incontestable prize” (MP 17), an “eternal fellowship with the living God” (ML 1.41), and as being “crowned with a garland of immortality” (MP 17). One text even describes martyrdom as the “medicine” of life (Cyprian, On the Glory of Martyrdom 23). Soon-to-be martyrs themselves are routinely described as “joyful” in anticipation of their death. This attitude was not, as some have suggested, due to a morbid fascination with the macabre; rather, it was a faithful anticipation of the reward and glory to come, echoing the words of Paul in Romans: “I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worth comparing with the glory that is to be revealed to us” (8:18).

Understanding this perspective on martyrdom also helps explain the Christian custom, common from the second century on, of celebrating martyrs’ deaths, especially on the anniversary of their martyrdom, by such practices as visiting their burial sites and reading their martyrdom accounts out loud in public liturgies. It was not the martyrs’ death that was being celebrated, however, but their life—their eternal life in the presence of God. So strong was this understanding that early Christians went so far as to call such days birthday celebrations! As St. Augustine says in a sermon commemorating the martyrdom of St. Cyprian:

I’m going to say something, you see, in praise of the most glorious martyr, Cyprian, whose birthday, as you know, we are celebrating today. . . . Why is this, brothers and sisters? What date he was born on, we don’t know. But because he suffered today, it’s today that we celebrate his birthday. We wouldn’t celebrate that other day, even if we knew when it was. . . . On this day he went away from the deep darkness of nature’s womb to that light, which sheds such blessing and good fortunes upon the mind. (Augustine, Sermon 310.1, in The Works of Saint Augustine III/9, trans. Edmund Hill, O.P., ed. John E. Rotelle, O.S.A. [New City Press, 1994], 68)

The notion of martyrdom as bringing the reward of new life led many Christians to call it a “second baptism.” As St. Cyprian himself put it: “In the baptism of water is received the remission of sins, in the baptism of blood [i.e., martyrdom] is received the crown of virtues” (Exhortation to Martyrdom, Preface 4, Ante-Nicene Fathers 5:497). Death by martyrdom, then, was not something to be feared; it was something to be received with joy because it led to life with God in its fullest form. Martyrdom became a witness to that final glorious end.

Imitation of Christ

Of all the theological themes presented in early Christian martyrdom texts, perhaps the strongest and most pervasive is that of martyrdom as the definitive form of the imitation of Christ. All Christians in the first centuries knew they were called to follow Christ and imitate him in their lives. Early martyrdom texts demonstrate the full extent of such discipleship, and speak explicitly of martyrdom as imitative of the Lord.

One of the earliest Christian martyrs outside of the New Testament was a bishop of Antioch named Ignatius. Arrested in Syria for his faith sometime in the early 100s, Ignatius was escorted by a group of cruel soldiers to Rome, where he was to meet his death. Along the way, the bishop wrote a series of letters to the churches in Asia Minor that had supported him, and he also sent a letter to the Christians in Rome, to be delivered ahead of his arrival. In that letter, in which Ignatius expresses his eagerness to face martyrdom and his prayers for the strength to do so, we begin to see a glimpse of his theological understanding of martyrdom.

Anticipating that his Roman brethren would be tempted to pull some strings to get him released, Ignatius pleads that they refrain from doing so. Drawing upon the imagery of sacrifice, he writes, “Grant me nothing more than that I be poured out to God while an altar is still ready” (Epistle to the Romans [hereafter ER] 5.3, in The Apostolic Fathers, vol. 1, trans. Kirsopp Lake [Loeb Classical Library, Harvard Univ. Press, 1998], 233). Later, he asks the Roman Christians to pray that he would become “a sacrifice through the instruments” of wild beasts.

His plea reaches its climax when he explains his understanding of martyrdom precisely in terms of imitation: “Allow me to receive the pure light; when I have come there, I will be a true man. Allow me to imitate the sufferings of my God” (ER 6.2–3). For Ignatius, full discipleship entailed being willing to suffer and die even as Christ did. Just as Christ died a sacrificial death on the Cross, so, too, Ignatius desired to offer up his own life as a sacrifice to God. As scholar Candida Moss puts it, for Ignatius, “discipleship and imitation were intertwined” (The Other Christs: Imitating Jesus in Ancient Christian Ideologies of Martyrdom [Oxford Univ. Press, 2010], 42), and martyrdom became the ultimate expression of both.

Indeed, for early Christians, martyrdom was the fulfillment of Christ’s own command about discipleship and imitation when he said, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me” (Matt. 16:24). A third-century martyrdom account from North Africa draws upon this idea, stating, “This is what it means to suffer for Christ, to imitate Christ even in his words, and to give the greatest proof of one’s faith” (The Martyrdom of Saints Montanus and Lucius 14, in ACM).

Origen of Alexandria also knew persecution and martyrdom first-hand. As a teenager, he witnessed his own father’s arrest and martyrdom, and he was spared the same experience only because his mother hid all his clothes, preventing him from going out. As an old man, he was imprisoned and tortured in the Decian persecution, dying afterwards from the wounds he received. Twenty years before that, however, in a.d. 235, he wrote An Exhortation of Martyrdom to encourage two of his fellow Christians to stand firm in the face of impending death for their faith. In that text, he quotes the words of Christ in the Gospels about taking up one’s cross, reminding them of the costly and imitative call of discipleship. Later in the same treatise, he describes the coming of martyrdom as “going in procession bearing the cross of Jesus and following Him.”

Martyrdom as the ultimate imitation of Christ is famously depicted in an account of multiple martyrdoms in Lyons in a.d. 177. In an outburst of sudden and violent persecution, roughly fifty Christians (many of whom hailed from Asia Minor) were arrested, tortured, and killed. Afterwards, a letter recounting the persecution was sent from Lyons to sister churches in Asia Minor, which explicitly stated that the Christians went to their deaths with “intense eagerness to imitate and emulate Christ” (Martyrs of Lyons [hereafter ML] 2.1, in ACM). One particularly moving passage depicts the death of a Christian slave named Blandina and her companions:

Though their spirits endured much throughout the long contest, they were in the end sacrificed, after being made all the day long a spectacle to the world to replace the varied entertainment of the gladiatorial combat. Blandina was hung on a post and exposed as bait for the wild animals that were let loose on her. She seemed to hang there in the form of a cross, and by her fervent prayer she aroused intense enthusiasm in those who were undergoing their ordeal, for in their torment with their physical eyes they saw in the person of their sister, him who was crucified for them. (ML 40–42)

In this passage we are given not only a verbal assertion that martyrdom is an imitation of Christ, but a visual depiction as well. Blandina hung on the post “in the form of a cross,” a direct reminder of “him who was crucified for them.” She imitated Christ even in the physical form of her martyrdom.

The most shining example of martyrdom as imitation of Christ, however, is the one we began with, the second-century martyrdom of Polycarp. The aged bishop of Smyrna followed a course clearly echoing the passion and suffering of Christ himself. Just as Christ predicted his coming death to his disciples, so Polycarp was given a vision, after which he prophesied his coming martyrdom. As Christ was betrayed by one of his own disciples, so Polycarp was betrayed to the authorities by a member of his own household. As Christ had the Last Supper with his disciples on the eve of his betrayal, so Polycarp had one last meal with his disciples as the soldiers drew near to arrest him. As Christ prayed “Thy will be done” in Gethsemane (Matt. 26:42), so Polycarp said, “May the will of God be done,” in refusing to try to escape. And as Christ triumphantly entered Jerusalem on a donkey six days before his Passion, so Polycarp was transported into the city on a donkey.

Moreover, the account of the death of Polycarp is replete with images of sacrifice. We are told that he “was bound like a noble ram chosen for an oblation from a great flock, a burnt-offering prepared and made acceptable to God” (MP 14). When the pyre was lit and the flames engulfed him, his body was “not as burning flesh but rather as bread being baked . . . and we perceived such a delightful fragrance as though it were smoking incense” (MP 15). Here we have a clear echo of Paul’s words in Ephesians describing Christ as “a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph. 5:2).

Recounted in this manner, the meaning of Polycarp’s death is obvious. It was a martyrdom, a “witness,” precisely in that it reminded those who beheld it (and those who later read about it) of the death of Christ. In this way, martyrs are declared “disciples and imitators of the Lord,” and “sharers with Christ” (MP 17, 6). As Bryan Litfin put it, the martyrs suffered “little passions of their own” (Early Christian Martyr Stories: An Evangelical Introduction with New Translations [Baker, 2014], 14), pointing to the decisive passion and sacrifice of Christ himself. Martyrdom thus witnessed to the possibility of a full imitation of Christ.

Participation with Christ

This brings us to the fourth and final strand of the early Church’s theology of martyrdom: participation with Christ. We have already heard that theme hinted at in the Martyrdom of Polycarp, which describes martyrs as “sharers with Christ.” Later in that account, Polycarp offers thanks to God for being considered “worthy to have a share . . . in the cup of Christ” (MP 14). This theme of sharing in the passion of Christ goes beyond mere imitation. As Paul Middleton explains, “The theme of sharing intimacy with Christ through mimetic suffering develops into the idea that Christ actually suffers within the martyrs” (Martyrdom: A Guide for the Perplexed [T&T Clark, 2011], 67).

We find this theme throughout early Christian martyrdom literature. Those who died at the hands of the Romans are said to have “put on Christ” and to have “intimacy with Christ” (ML 1.42, 1.56). In their suffering and death, they are said to have “Christ suffering in them” (ML 1.23) and to have “become one with the Son” (EM 39).

The language of union and participation with Christ is found on the lips of martyrs themselves in two particularly moving accounts. One is the trial record of the martyrdom of the deacon Papylus in Asia Minor. After a brief interrogation, Papylus was ordered to be scraped with claws for his refusal to recant and sacrifice to the gods. After three rounds of this brutal treatment, Papylus “had uttered no cry of pain (but like a brave athlete he beheld the fury of the adversary in great silence).” In response, the presiding proconsul admitted to the cruelty of the punishment and then offered the deacon a chance to speak. Papylus’s reply underscores our fourth theme of martyrdom: “These torments are nothing. I feel no pain because I have someone to comfort me; one whom you do not see suffers within me” (The Martyrdom of Saints Carpus, Papylus and Agathonice 3, in ACM).

According to Papylus, the experience of martyrdom itself had its own consolation; there was not simply the anticipation of the reward to come afterward, but also the consciousness of Christ’s immediate presence at the time. The deacon’s persecutors may not have been able to see Christ, but for Papylus he was there, suffering within him. His experience of suffering was alleviated not just by the knowledge that he was imitating Christ in taking up his own cross, but also by a mystical participation and union with Christ in the suffering itself.

That same theology is found yet again in the Martyrdom of Perpetua and Felicity. The scene takes place in a jail cell, where Felicity, a young slave-girl now eight months pregnant, fears “that her martyrdom would be postponed because of her pregnancy” (it being against Roman law to execute a woman with child). Her companions in prison, also distressed that she might be left behind when they are called to the arena, begin to pray. Immediately afterward, Felicity goes into labor and begins crying out in pain. Seeing this, one of the Roman soldiers begins to mock the young girl, saying, “You suffer so much now—what will you do when you are tossed to the beasts? Little did you think of them when you refused to sacrifice.” Felicity’s response is both immediate and profound: “What I am suffering now, I suffer by myself. But then [in the arena] another will be inside me who will suffer for me, just as I shall be suffering for him” (MPF 15).

Like Papylus, Felicity understood martyrdom to hold a consolation in itself precisely because of Christ’s participatory presence in her suffering. Indeed, for Felicity, there was a marked difference between the suffering of labor and the suffering of martyrdom. The first she suffered alone, in her own strength; but the latter brought with it a new grace and strength not her own, namely, the very presence of Christ himself within her.

Martyrdom, then, was for these early Christians a powerful witness to the supernatural grace and strength that came from a deep, intimate union with Christ in suffering. Because of this participation with Christ, martyrdom was not a matter of enduring by a sheer act of the will or by a simple fortitude of the mind resisting an antagonistic world. Rather, it was the pinnacle of intimacy and union with Christ.

Conclusion

Because the Christian martyrs of the first three centuries faced their accusers and refused to recant and deny the name of Christ, their lives (and their deaths) have become living witnesses to something more than simply standing up for what they believed in. They also witness to the cosmic spiritual battle taking place in the hidden realms; to the promise of reward and joy that comes to those who persevere to the end; to the full imitation of Christ exemplified by following in his steps even unto death; and, above all, to the union and intimacy with Christ that comes when one’s suffering is woven together with the suffering of Christ himself.

Because of this manifold witness, the gruesome, bloody details in the accounts of Christians who died at the hands of the Romans are not meant to instill fear and despair; rather, they are intended to encourage all of us living Christians to rejoice in the heavenly call of our brothers and sisters, and to inspire us to follow in their footsteps if called to do so. For they could see martyrdom for what it really was: a witness “in accord with the pattern of the gospel of Christ.”

Bryan A. Stewart is Professor of Religion at McMurry University in Abilene, Texas, where he teaches the history of Christianity. In addition to scholarly articles and essays, he has published a monograph entitled Priests of My People: Levitical Paradigms for Early Christian Ministers (Peter Lang, 2015), and has a volume coming out in March in The Church's Bible series: The Gospel of John: Interpreted by Early Christian and Medieval Commentators (Eerdmans). An ordained Anglican priest in the traditional Diocese of Fort Worth (ACNA), he serves as the vicar of Holy Cross Anglican in Abilene.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on martyrdom from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor