View

The Messiah's Beauty

Michael Martin De Sapio on Benedict XVI on the Fairest of the Sons of Men

Throughout his life Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI has impressed on us the importance of beauty as a pathway to God—in the liturgy and elsewhere. This side of Benedict is given eloquent expression in "Wounded by the Arrow of Beauty: The Cross and the New 'Aesthetics' of Faith," which was written when he was still Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger; it appears as a chapter in the book On the Way to Jesus Christ. It is a most affecting piece, one that opens windows onto a number of new vistas for the searcher of beauty (of which I will have more to say later).

Benedict takes as his starting point two starkly contrasting texts for the Passion Week liturgy:

"You are the fairest of the children of men and graciousness is poured upon your lips." (Ps. 45:2a)

"He had neither beauty nor majesty, nothing to attract our eyes." (Is. 53:2)

Church tradition has assigned these texts the status of messianic prophecies. The first, from a royal wedding psalm, describes the resplendent beauty of Christ—in particular the inner beauty of his teaching. The second brings before our eyes the bruised and battered Christ of the Passion, whom Pilate presented to the crowd, exclaiming "Ecce homo!"—"Behold the man!"

Benedict attempts to reconcile the seeming contradiction between these two prophecies. He discusses the classical Grecian ideal of beauty and how Christianity brought in its place a new conception of beauty, which included suffering and the Cross. He concludes that in Christ, the Grecian ideal is not destroyed but transcended: Christ is the one who "can risk setting aside his external beauty in order to proclaim, in this very way, the truth of beauty."

Benedict says that the question of whether Christ was beautiful was an important one to the church fathers, although he doesn't go into any more detail on the subject. Perhaps it is not unreasonable to suppose that the Son of God possessed perfect corporeal beauty, much like a Greek hero. But where Christ transcended Apollo was in laying aside his beauty for our sake to meet ugliness and sin head-on, in this very way showing us the truth of beauty. The story does not end there, however, for Christ at last showed us his glorified resurrected body. That we Christians believe in a bodily resurrection, in fact, affirms the imperishable beauty of what God has made.

Tricks of the Devil

Benedict proposes two ways in which the face of beauty can be distorted—two dangers that Christianity must oppose. The first is the "cult of the ugly." Modern man—partly as a response to the brutality or banality of the world around him—comes to doubt whether beauty is the true reality after all and wonders if ugliness is perhaps not the real truth of the universe. The cult of the ugly turns Greek idealism upside down. The depiction of the "cruel, the base and the vulgar" (in Benedict's words) becomes the norm.

It is easy to connect Benedict's "cult of the ugly" with much of the visual art, music, literary fiction, and movies of recent times. Our dominant mode today is a base naturalism, which seeks merely to reflect "the way things are," which is, it is tacitly assumed, without any transcendent purpose. In fiction, the cult of the ugly expresses itself in an unrelentingly cynical or pessimistic worldview, devoid of the redemptive. In music (both serious and popular), there is a flight from concord toward noise. In architecture, we have drab geometrical structures devoid of ornament. Meanwhile, the very search for beauty is scorned by some in the art world as a retreat into escapism and unreality.

On the other side of the "cult of the ugly" lies the cult of false beauty. Here Benedict's argument becomes more subtle: the Christian is not simply to distinguish beauty from ugliness, but must also differentiate between true beauty and deceptive beauty. When beauty's transcendent character—its connection to God and to the Logos—is not recognized, it becomes mere prettiness, superficial and cosmetic. The result is that society becomes strangely indifferent to beauty, relegating it to the status of the trivial and dispensable. Benedict speaks of a "superficial aestheticism and irrationality." One recalls how beauty and art can be debased to the level of a social accessory or simply become the vehicle for an irrational spewing-forth of the artist's subjective feelings. Either way, the serious and God-like character of beauty is not given its due.

True beauty, Benedict reminds us, is ennobling; it leads us outside ourselves to encounter the Other; it is geared toward the contemplation of Being. False beauty, by contrast, functions as seduction, as an incitement to lust and power-seeking, and it closes the beholder in on himself. Benedict traces this false beauty back to Genesis, when Eve grasped the apple proffered her by the serpent, finding it "delightful to the eyes." He also evokes the delusion of eroticism masquerading as beauty, as in advertising billboards that tempt men to selfishly seek satisfaction. Such "beauty" is mere sensual allurement, devoid of transcendence and of the human element that leads us to encounter the Divine Person.

For Benedict, the cult of the ugly and the cult of false beauty are tricks of the devil that blind us to reality. Escaping these delusions leads to the liberating realization that "it is not the lie that is 'true'; rather, it is the truth." And the ultimate truth is found in the image of the Crucified Christ, who overcame ugliness and sin.

A Form of Rhetoric

I mentioned that "Wounded by the Arrow of Beauty" opens up new avenues of thought for the lover of art. As a classical musician, I have come to admire the work of the conductor and musician Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1929–2016), of the same generation as Pope Benedict, who exerted great influence in the early music revival, first in his native Austria and then internationally. In rereading his influential book, Baroque Music Today: Music as Speech,I was intrigued to find that his writing style, in English translation, has a similar ring to Benedict's, even though he is writing about music rather than theology; and that the insights of the two men on the nature of beauty harmonize well. Both would agree that we must "go beyond Apollo" and that, as Benedict says, "a merely harmonious concept of beauty is insufficient."

For Harnoncourt, as for Benedict, beauty and art are indispensable to man. Harnoncourt's thesis is that music nowadays is merely a pleasant ornament to our lives, not an integral part of life, as it was in the age of the great Baroque composers. Music has lost the power to startle and move and change us. Once an adjunct to worship and a mover of the passions, music has become merely decorative, like a floral arrangement. We demand no more of it than to bask in it passively. Accordingly, part of Harnoncourt's project was to rediscover the high purpose that music had in Bach's day as a bearer of meaning and truth—as a form of rhetoric. "Music is a language based on tones," he says, "involving dialogue and dramatic confrontation."

Harnoncourt's conception of music as a form of speech ("sounding rhetoric" is another possible translation of the original German) finds its counterpart in Benedict, who stresses the connection of Christ's beauty with truth and revelation. One might say that the Crucifixion speaks to us; in beholding an icon or other depiction of it, we behold a sermon from God himself. This is why Christian art always contains the human figure, not confining itself to geometric abstractions as does Islamic art; God's Logos or self-revelation is summed up in the fleshly person of Christ, specifically in Christ Crucified.

A Bearer of Truth

For Harnoncourt, beauty and ugliness are necessary counterparts. He speaks at one point of the "pleasurable pain" produced by certain melodic and harmonic combinations in music, the interplay of dissonance and consonance. Benedict points to a similar paradox in speaking of beauty as something that "wounds" us, startles us, and brings us out of ourselves. Indeed, some great artworks have the power to shock.

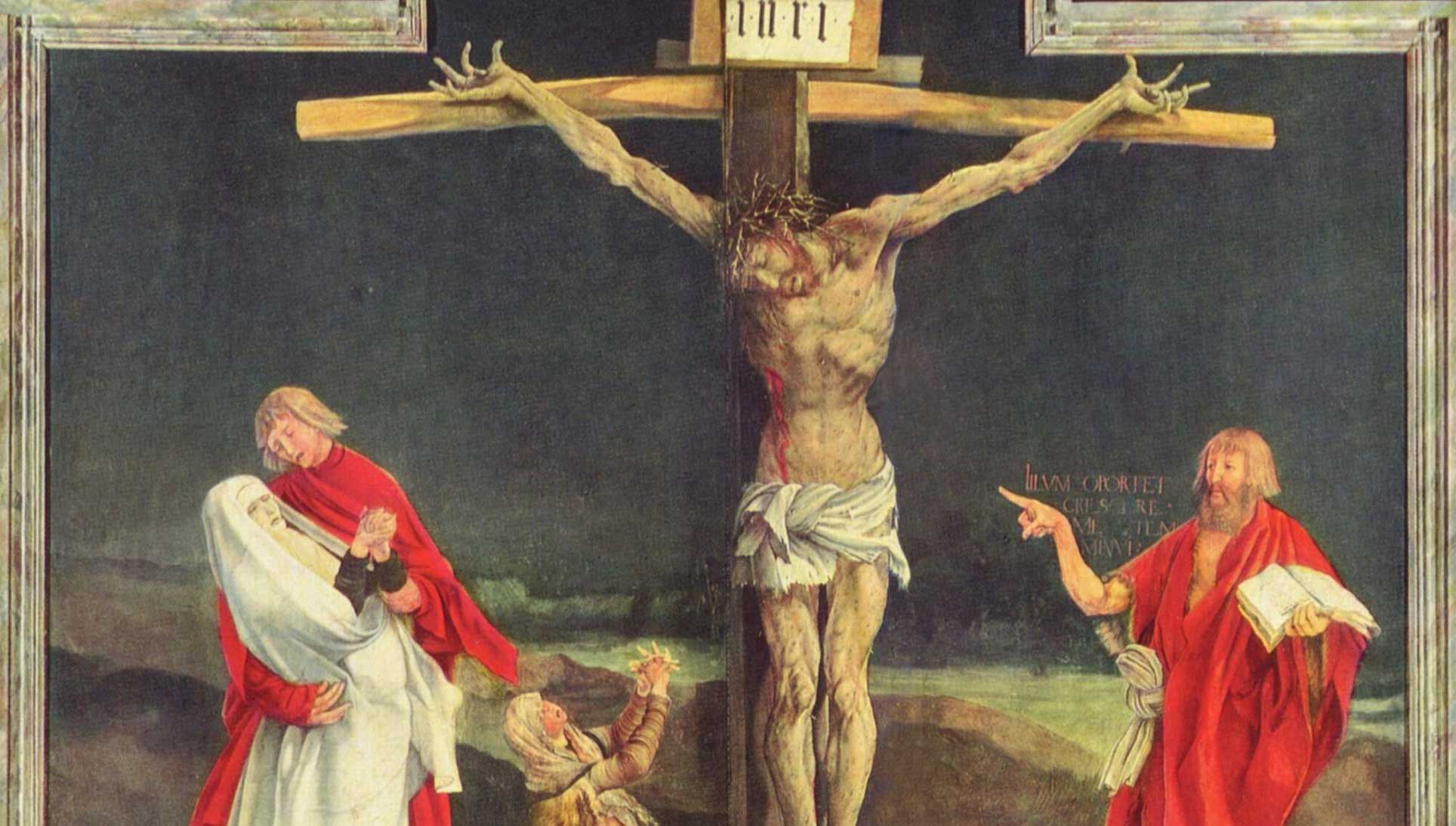

To behold the Isenheim Altarpiece, Matthias Grünewald's gruesome Crucifixion picture, is certainly not to behold an image of ideal beauty in the Grecian tradition based on the idea of bodily health and strength. This Christ, with his twisted and tortured body, is far from an Apollonian prototype. Nevertheless, suffering and ugliness are here transformed into a thing of beauty by the artist, as indeed they were transformed by God himself on the Cross.

Benedict says that in Christ, "the experience of the beautiful has experienced a new depth and a new realism." Harnoncourt, for his part, wants music to be a bearer of truth and realism. Rather than a bubble bath, such beauty is sometimes more like a cold shower. Harnoncourt became famous in part for his startlingly dramatic and rhetorical performances of such works as the Passions of J. S. Bach. And it is a performance of Bach (a cantata conducted by Leonard Bernstein) that Benedict cites as a pivotal personal experience, which brought home for him the feeling of being touched by beauty—touched, he says, by the personal presence of Christ.

Return to Sources

Pope Benedict XVI and Nikolaus Harnoncourt are not dissimilar figures. Each was involved with a movement, Benedict in theology and Harnoncourt in music, that involved a "return to the sources." Benedict's movement was the so-called nouvelle théologie, which aimed at recovering the sources of Christian thought in the church fathers so as to temper the dominant neo-Thomism of the day. Harnoncourt's movement was called Historically Informed Performance, which attempted to reconstruct musical performance styles of the past by consulting original written source material, thus correcting centuries of mistaken habits. The ultimate aim of both movements was to revitalize our cultural and intellectual traditions.

Those cultural traditions can be a powerful means of discovering beauty, as both thinkers recognize. Benedict advocates a sort of "apologetics of beauty," using the classics of Christian art to lead others to the faith. Harnoncourt, for his part, devoted his whole career to bringing the classics of Western music vividly to life for a new generation of audiences, "evangelizing" us to the message of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven.

These are indelible accomplishments, as is the body of writing that each man left. For me, the most exciting thing about their aesthetics is that it calls man to a high vocation as a critic and connoisseur of beauty: a vocation with the capacity—indeed, the obligation—to distinguish beauty from ugliness and true beauty from false. It is in pursuing true beauty in this life that we come, by degrees, to encounter the supreme Beauty of God.

Michael Martin De Sapio is a writer and classical musician from Alexandria, Virginia. He is a frequent contributor to such journals as Crisis, Fanfare, and The Imaginative Conservative on topics ranging from religion to cultural history and music. As a musician, he specializes in the Baroque violin and is also an avid amateur chorister in Roman Catholic churches.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor