Feature

The Age of Reformations

The Critical History Before, During & After Martin Luther by James Hitchcock

Part 1: A Troubled Period

Movements once variously designated as the Christian Renaissance, the Protestant Reformation, the Protestant Revolt, the Catholic Reformation, and the Counter-Reformation are, from a historical point of view, perhaps now best understood as part of something that might be called the Age of Reformations—two centuries of both notorious corruption and genuine renewal.

It was one of the Catholic Church's most troubled periods, as the over-reaching papacy of the thirteenth century was brought low and entrapped in its own coils, providing little spiritual leadership.

The movement of the papacy from Rome to Avignon caused the popes to be seen merely as contestants in an international power struggle. But their eventual return to Rome provoked the even greater scandal of the Great Western Schism, when there were first two, then three, rival claimants to the papal office, a schism that was ended by the Council of Constance in 1415. Conciliarism—the claim that ultimate ecclesiastical authority resided in the general councils—was proposed as a guard against a corrupt papacy, but subsequent popes rejected it. After their return to Rome, the popes were obsessed with the Italian wars, and powerful families engaged in cutthroat competition for the papal office.

Demands for reform echoed continuously. The clergy were condemned for greed, lust, laziness, dishonesty, and other real or imagined sins. Monks and nuns were accused of violating their vows by fornication and living in quasi-luxury. Bishops were wealthy and politically powerful. Pluralism—holding more than one benefice at a time—and the absenteeism that necessarily accompanied it, were increasingly tolerated. Nepotism was also rife.

Most lay people did not, however, lose their faith. Traditional piety still had great power, and the invention of printing around 1450 allowed religious books of all kinds to be published.

Devotion to Christ in his Passion and to the Virgin Mary was pervasive, as was devotion to the Eucharist, although communion was received only occasionally. Devotion to the saints continued at the heart of popular piety, along with much credulity about the supernatural. Shrines were visited by large numbers of pilgrims. Preaching was highly valued, sometimes from outdoor pulpits. The deathbed was the crucial moment when the soul was suspended between salvation and damnation. Indulgences—applicable to both the living and the dead—could alleviate the sufferings of Purgatory.

Atmosphere of Anxiety

The Black Death of 1347–1349 was the greatest natural disaster in Western history, and partly because of it an atmosphere of spiritual anxiety, even of dread, hung over the age. Ritual flagellation was practiced by organized groups of lay people, who went in processions from town to town to expiate their sins. (Popes forbade the movement, which was treated by the Inquisition as a heresy.)

Possibly because of this anxiety, witchcraft, which had attracted relatively little attention in the Middle Ages, came under increasingly fanatical scrutiny from the late fifteenth to the late seventeenth centuries, proving to be an area of unhappy ecumenical agreement.

The tension between spontaneous fervor, the demand for reform, and ecclesiastical authority was played out especially by the Spiritual Franciscans, who declared that prelates who did not practice poverty had no authority, since absolute poverty was the mark of a true Christian. These Fraticelli ("little brothers") were condemned as heretics, but with the support of the German emperor their influence continued.

The two "morning stars" of the Reformation—John Wyclif and John Hus—took radical stands, both seeming to claim that a sinful priest could not validly administer the sacraments and denying transubstantiation, confession to a priest, indulgences, clerical celibacy, and the veneration of images and relics. Both were condemned as heretics, but for a time they were protected by powerful nobles. Wyclif died in bed, but Hus was burned at the stake. However, Wyclif's movement survived solely among unlearned people called Lollards ("psalm-singers"), while the Hussite movement permanently divided Bohemia along religious lines.

The fervent piety of the age caused dissatisfaction with what seemed like the oppressive complexity of church life—theology was an academic discipline incomprehensible to most people; Canon Law was a bewildering system of legalisms; the liturgy was celebrated at a distance from the laity; and devotion to the innumerable saints was often competitive.

On the one hand, God seemed inaccessible, requiring the believer to navigate a complex system of doctrines, laws, and practices. But at the same time, he was overly accessible, seemingly obligated to respond to successful navigators.

Thus, much of the religious spirit of the age expressed itself outside formal church structures, although not necessarily in opposition to them. For many, religious experience seemed to be the surest path to God, a liberation from burdensome traditions in order to return to an earlier purity.

Brethren of the Common Life

The origin of much of this was in the Netherlands, notably with the Beguines and Beghards (the origin of the names is uncertain)—semi-monastic but essentially lay movements that were at first condemned but later given cautious approval.

Gerard Groote accepted ordination as a deacon only so that he could preach. Although he was not in favor of monastic life, he attracted followers and formed a community called the Brethren of the Common Life, with houses for both men and women. Members took no vows, were free to leave at any time, and lived a simple life, supported by their own labors. Groote formulated what came to be called the New Devotion, whose novelty lay entirely in its simplicity.

Its greatest expression was The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas à Kempis, which urged readers simply to follow the teaching and example of Jesus in the Gospels—the spirit of humility, charity, and submission to God's will. While not denigrating practices like pilgrimages or devotion to Mary (part of the book was an extended meditation on the Eucharist), Kempis identified stages in the soul's rise, of which a love of suffering for Jesus' sake was the highest.

There was a distinct note of anti-intellectualism in the work. Kempis warned that, in itself, knowledge might be sterile, whereas a heart-felt desire to do God's will was salutary. Actual emotion was a necessary sign of authenticity—the penitent should shed real tears and experience desolation.

Some of Wyclif's followers made a partial translation of the Bible into English, which caused the English hierarchy to set their face against a vernacular Scripture. The Bible had been translated into the Czech language, and Hus cited it as an authority against that of the Church. The Brethren, who taught in schools that stretched across Northern Europe, also placed great emphasis on reading the Bible but in an uncontroversial way—to inculcate piety and morality.

Northern Mysticism

The highest expressions of late medieval piety were mystical, a phenomenon in which the soul transcended all objective manifestations of God—even conscious thoughts—and encountered him directly, amidst overwhelming light. Along with the New Devotion, mysticism was to a disproportionate degree a Northern phenomenon, manifesting a kind of spiritual searching that was less evident in the South.

It necessarily produced ambiguous, sometimes opaque, writings—Meister Eckhart of Hochheim, Henry Suso, Jan Ruysbroeck, Johann Tauler, the anonymous German Theology, and the English mystics Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton, Julian of Norwich (a woman), and the anonymous Cloud of Unknowing.

The searching spirit of piety had significant intellectual parallels. Contrary to Thomas Aquinas, John Duns Scotus held that the mind could only know individual beings, a claim that rendered Aquinas's great synthesis of knowledge—his teaching that the entire universe constitutes an intelligible whole—less credible.

The principal movement of late medieval philosophy came to be called Nominalism. William of Ockham held that the mind did not know real things, only its own ideas, to which it gave names. Like mysticism, Nominalism had an acute sense of the absoluteness of God, far beyond all human categories of understanding, whereas both Thomistic theology and formal religious practices seemed to make God accessible.

This fideism implied a voluntaristic morality—right and wrong were simply decreed by God's inscrutable will and were not open to human understanding in the way that Dante, for example, thought they were. Some late-medieval theologians held a theory of predestination, since otherwise human beings would have the power to force God to grant them salvation.

Nicholas of Cusa, a German cardinal, was the most original mind of the age. He deemphasized rational speculation, positing the Infinite as the ultimate reality, knowable only by semi-mystical intuition. All religions contained some truth (he urged the study of the Qu'ran, which he thought would prove the truth of Christ), but Christ alone embodied the full truth, resolving all contrarieties.

Italian Humanism

The intellectual life of Italy, although also manifesting a spirit of searching, moved in a quite different direction from that of the North. The movement later called the Renaissance was made up of "Humanists" seeking to recover ancient classical civilization.

They began merely with an interest in "humane letters," including grammar, rhetoric, history, and poetry—the "liberal arts." Most of the Humanists remained believing Catholics, but they treated the passions and the imagination as being as important as reason and considered the medieval Scholastic philosophers' arid "logic-chopping" to be remote from human concerns. The Scholastics engaged in sterile attempts at definition, but rhetoric and poetry could move the heart and thereby bring about genuine conversion.

The Greek language had been largely forgotten in the West for centuries, but by the later fourteenth century it was an essential part of Humanist education. Humanists paid attention to the New Testament primarily through literary analysis—the precise meaning of words, metaphors, and other poetic qualities. Several of them made Latin translations of the New Testament, working from old Greek texts in order to offer an alternative to the Vulgate, while Giovanni Manetti learned to read Hebrew and translated parts of the Old Testament. The Humanists also published patristic texts, including those of the Eastern fathers. The Humanists' study of the classics gave them a keener sense of history than their predecessors had and a certain skepticism about historical claims. Lorenzo Valla wrote a commentary on the Greek New Testament that called into question certain passages of the Vulgate.

Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch), the first important Humanist, accused the Scholastics of being more familiar with Aristotle than with Moses and Christ. Aristotle was spiritually deficient, because although he could define virtue, his words lacked the power to motivate men to lead virtuous lives. It was not possible to know God adequately in this life, but it was possible to love him, which made virtue far more important than knowledge. Platonism was an alternative to Aristotelianism, with Augustine's intensely personal Confessions serving as a model of theology.

Perhaps the most important of the Italian Humanists was Marsilio Ficino, who wrote a Platonic Theology based on the Augustinian teaching that the image of God could be discovered in the soul. All significant truth was contained in Plato, but Jesus was the mediator who led men by stages from the earthly to the spiritual realm. Giovanni Pico della Mirandola undertook to show that all systems of belief are ultimately compatible.

Humanism was in many ways a lay phenomenon, but Petrarch was in minor orders and Ficino was a priest. One of the greatest Renaissance artists, Fra ("Friar") Angelico (d.1455), was a Dominican mystic.

But the great ancient writers were pagans, which inevitably raised questions about the significance of the coming of Christ. There was consensus that the pagan poets, having concealed their monotheism behind a fanciful polytheism, at least offered glimpses of the divine. Petrarch grieved that Cicero did not know Christ but took comfort in the thought that at least he had knowledge of the one true God. Like Jerome, Petrarch found Scripture inferior to pagan writings in literary

quality.

Differing Views of Human Nature

The fundamental ambiguity of Humanism was its view of human nature—whether man was good or, left to himself, capable of great evil. Without explicitly denying Original Sin, some Humanists seemed to believe in basic human goodness. Following classical models, they were trustful of the natural virtues and extolled freedom.

Petrarch wrote On Human Dignity, seeing man as lower than the angels in absolute terms but higher by virtue of having been redeemed by Christ and having been given lordship over nature. But he also related how he once climbed a mountain to admire the beauty of the world, but at the summit opened Augustine's Confessions and was stunned to read there a warning that men admire high mountains but neglect their own souls. He saw his "aimless wanderings" as a yearning for salvation and vowed henceforth to concentrate on God.

Pico's "Oration on the Dignity of Man" became the most famous of all Renaissance texts, departing from the idea of a fixed hierarchy and celebrating human subjectivity, which gave man the freedom to aspire to the divine but carried with it the possibility of a great fall.

Valla was unique in being a Christian Epicurean, insisting that there could be no such thing as natural virtue and that supernatural virtues were the means by which men, who were like animals in everything except their immortal souls, curbed their earthly pleasures in order to live for the eternal pleasure of heaven. (Valla thought there was no inherent value in sexual continence, and some Humanists, including the future Pope Pius II, wrote scabrous and even obscene verses.) Valla questioned why the term "religious" should be reserved for those who took vows, since some lay people were exposed to greater perils in the world than were monks in the cloister and therefore deserved greater credit.

Contrary to Christian teaching, classical authors encouraged pride in the achievement of fame and power, and Renaissance Italy also valued the accumulation of wealth. But consciences were not fully at ease, so that merchants and bankers often commissioned works of religious art, even entire churches, as acts of penance for having been too worldly.

Traditional piety still had strong influence, reaching its climax with the Florentine Dominican Girolamo Savanarola, who appeared as a prophet of fire and brimstone, warning the Florentines that their worldly ways would lead to eternal damnation. Many (including Pico) came forward to throw rich tapestries, clothes, jewels, even books and paintings, onto the "bonfire of the vanities" that Savanarola kindled. (Pope Alexander VI arranged for Savanarola to be burnt at the stake on a trumped-up charge of heresy.)

Artistic creativity continued to be devoted primarily to biblical subjects or the lives of the saints. But subjects from pagan lore were also common, as was the new art of portraiture—likenesses of people that showed their individuality and their characters. Every Renaissance pope supported Humanism. Popes were the greatest artistic patrons—they launched a Roman rebuilding program that lasted two hundred years and commissioned Michelangelo and other artists. The Vatican Library became the greatest collection of manuscripts in the West.

Northern Humanists

Northerners were aware of Italian Humanism and often made sojourns in Italy to imbibe it, but some Northerners found Italian Humanism too pagan. Partly because it interacted with the New Devotion, Northern Humanism developed in more consistently Christian ways than in Italy.

Paradoxically, however, this had the consequence that Northern Humanists were sometimes more radical than the Italians. There was a blunt spirit in the North that demanded answers to troublesome questions, in contrast to the easygoing sophistication of Italy.

Wessel Gansfort, a Netherlander educated by the Brethren of the Common Life, insisted that he believed nothing contrary to the Catholic faith, but at various times he seemed to teach the primacy of Scripture over Church, justification by faith, and the priesthood of all believers, and to deny Transubstantiation, indulgences, Purgatory, and the need for confession.

Conrad Celtis was unusual among Northern Humanists in not having been educated by the Brethren and even more unusual in being a kind of pagan in his open embrace of hedonism. He doubted the immortality of the soul and ridiculed Transubstantiation and other Catholic doctrines, although he also had a certain semi-superstitious devotion to the Virgin Mary and the saints.

Johannes Reuchlin learned Hebrew in order to study the Old Testament and the Kaballah. (The Dominicans of Cologne obtained a ban on the reading of Hebrew books, but a few years later, Leo X sponsored the publication of the Talmud in Rome.)

Jacques Lefevre d'Etaples (Faber Stapulensis) was the first great French Humanist. He made a Latin translation of Paul's letters that seemed to express the doctrine of justification by faith, and he later produced the first complete French Bible.

The English priest John Colet, although he studied in Italy, thought that the pagan classics had no relevance to Christianity. He, too, devoted his scholarship to Paul's letters, paying close attention to their words and literary style and largely ignoring centuries of commentaries by theologians in order to expound their meaning with a fresh eye. Colet combined the love of learning with a reforming zeal that was characteristic of some Christian Humanists, denouncing the financial burdens placed on the laity, the abuse of benefices, and legalism and exhorting the clergy to begin to reform the Church by reforming themselves. In a sermon before the court of Henry VIII, he condemned the propensity of Christians to make war on one another.

Colet befriended the Netherlandish Humanist Desiderius Erasmus (Erasmus of Rotterdam) and persuaded him to turn his attentions away from purely literary pursuits and to the Bible itself. In time, Erasmus became the "prince of Humanists" and the most influential intellectual of his age. He also embodied the religious ambiguities of that age. Educated by the Brethren, he imbibed their devotion to biblical piety but found their spirit rigid and narrow. Aspiring to a life of learning, he became a monk but then left because he also found monastic life too constricting.

Erasmus was the rare scholar who was also capable of reaching a general audience. Throughout his career, he questioned, usually through satire, many aspects of traditional Catholicism—the piety of simple people, the hypocrisy of monks and nuns, academic theology, power-hungry prelates. He was deliberately ambiguous about his real thoughts. Especially from his satires, many people inferred conclusions that Erasmus himself did not state forthrightly—that not only was the monastic life corrupt, it was not an authentic Christian vocation; that not only did sacramental ritual foster a credulous magic, it was an obstacle to faith; that not only was the great edifice of formal dogma remote from the spirit of the gospel, it was a distortion of Christ's teaching.

Some of those who drew those conclusions condemned Erasmus as a heretic, while others welcomed him as a liberator from religious tyranny. Erasmianism became a reform program with fluid boundaries, aimed at a simplification of the Christian life made possible by a direct encounter with the gospel. His principal life's work was the recovery of what he considered authentic early Christianity, especially the fathers of the Church, by making use of the tools of learning. Although he favored vernacular translations of the Bible, his greatest achievement was an edition of the Greek New Testament, based on the best manuscripts he could find.

Thomas More was a friend of both Colet and Erasmus, a layman in the service of Henry VIII. But More was unlike Erasmus in his very traditional kind of piety. He, too, championed Humanist learning, but he was powerfully attracted to the monastic life.

A Council & New Communities

Early in the sixteenth century there were visible movements for Church reform. The Spaniard Cardinal Francisco Ximenes de Cisneros was the first great reforming prelate. Personally austere, he warred on clerical corruption, opposed the collection for the new St. Peter's Basilica, founded a new university for the education of the higher clergy, and encouraged the production of a Bible that printed the Hebrew and Greek texts alongside the Vulgate. He also favored forced conversions of Jews and Mulims, probably seeing this as related to reform.

The Fifth Lateran Council (1512–1517) was the first serious official attempt to reform abuses. Its most prominent figure was Giles of Viterbo, who articulated the orthodox Catholic idea that "Religion reforms men; men do not reform religion." Giles recalled the Church of his day to the purity of the primitive Church and was quite blunt in blaming recent popes for most of the abuses, although he professed great hope for Leo X.

The revival of sacred learning and the discovery of the New World marked the beginning of a great new era, Giles predicted, and—ironically, in view of what would soon happen—so, too, did the great project to build a new St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.

Giles was "Evangelical" insofar as he advocated a closer study of Scripture, including the still-controversial use of the Hebrew Old Testament, although he also referred to "obstinate Jews" who willfully ignored the meaning of their own prophecies.

Much of the impetus for reform originated with visionary leaders who founded new religious communities.

The survival of the Fraticelli led to the founding of a new Franciscan group, who were called Capuchins because of the distinctive style of their hoods. Their members wore rough clothes and untrimmed beards, espoused radical poverty, and devoted themselves to works of charity and to preaching in a plain, emotional, popular style.

The Oratory of Divine Love was founded in Venice—in some ways Europe's most worldly city—by a group of priests and laymen who sought to live a fuller Christian life. Three of them became major figures in the Catholic Reformation. Gasparro Contarini served his city as a diplomat. Like many devout people of his time, he was dissatisfied with formal piety, and in 1511 he had a religious experience similar to that which Martin Luther had around the same time—an acute awareness of his own sinfulness, the futility of human effort, and his absolute dependence on God's grace. The fact that Contarini remained a layman was indicative of the uncertainties of the age, in that, traditionally, a conversion experience like his would have led to a monastery. Instead, he entered the papal service and was eventually raised to the cardinalate, accepting ordination only when he was named a bishop.

Reginald Pole was an Englishman of royal blood who imbibed the Humanist spirit in Italy and befriended Contarini. A third founder of the Oratory, Gian Pietro Caraffa, was a bishop and papal diplomat who eventually ascended the papal throne as Paul IV.

Out of the Oratory of Divine Love there developed a new religious community dubbed the Theatines, after the diocese where they were founded. Its members, including Caraffa, departed from custom in that they wore no distinctive habit and did not chant the Divine Office in common, devoting themselves to preaching and to works of charity.

Contarini and Pole were at the center of a loosely unified group that came to be called the "Spirituals," because they identified the principal problem of the Church as the weakness of deep inner faith and they urged spiritual regeneration as the essence of reform. They were attracted to the Pauline doctrine of justification by faith because it demanded inner conversion, and they were wary of the idea of "good works."

Caraffa, although linked with Contarini and Pole by a commitment to the reform of abuses, nonetheless looked on the Spirituals with increasing suspicion and became in effect the head of a rival reform party dubbed the "Zealots" because of their determination to use disciplinary means to correct both heresy and moral disorders.

Ignatius Loyola & the Jesuits

By far the most influential of the new religious communities was the Society (originally Company) of Jesus, whose enemies sarcastically pinned on them a negative epithet that stuck—Jesuits.

Ignatius Loyola was a minor Spanish nobleman and soldier who, during a long convalescence from a wound, underwent a conversion from conventional piety to a burning desire to be a knight for Christ. At first he explored traditional channels—visiting monasteries, living for a time as a hermit, imagining a crusade against the Muslims, and actually visiting the Holy Land. At the University of Paris he attracted a small band of companions, most of them laymen like himself, who sought to live the spiritual life in a deeper way.

Ignatius still hoped to go to the Holy Land to convert the Muslims, but he and his followers were unable to get a ship for the Near East. This failure caused Ignatius to conclude that such was not God's will, and he and his companions went to Rome to place themselves in the hands of the pope, spending their time visiting the sick, aiding the poor, instructing children, preaching, hearing confessions, and offering spiritual direction. Contarini befriended them, and in 1540 Paul III recognized them as a new religious order, allegedly exclaiming as he did so, "I see the finger of God here!"

The rule that Ignatius presented for papal approval was in certain ways revolutionary, in that it departed significantly from the patterns of monastic life. Jesuits, too, wore no distinctive habit and, most controversially, not only did not gather to recite the Divine Office in common, were actually forbidden to chant it. Each priest was to recite it privately. The point of this was to orient the Jesuit towards activity in the world, eliminating those things that might impede apostolic zeal. Against the concern that such a regimen might produce worldly men with no spiritual depth, Ignatius prescribed an unusually long period of training and an intense program of personal prayer and meditation.

All Jesuits took the traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and an elite took a fourth vow of special obedience to the pope. Unlike the quasi-republican structure of the monastic orders, Ignatius created a highly centralized organization, emphasizing obedience in the paradox that free will is most fully exercised by free acts of submission.

Ignatian spirituality could be characterized as a kind of holy pragmatism—discerning what was necessary to fulfill God's will without regard for one's own desires. Jesuits were to judge the most effective way of winning people to Christ in particular situations—sometimes boldly and sternly, sometimes by indirection. They had to have no love of worldly things, but asceticism was to be practiced only in moderation.

Ignatius directed the early Jesuits towards a variety of activities—as theologians and controversialists, advisors to princes, preachers, confessors, pastors, and (above all) missionaries. At the university level, they were orthodox Thomists, but their network of secondary schools incorporated the Humanist study of the classics.

Part 2: Reforms & Divisions

As Lateran V drew to a close, Giles of Viterbo was probably unaware that, as general of the Augustinians, he was the ultimate superior of a man who, within a few months, would eclipse everything the council had done. The possibility of orderly, gradual reform had been overtaken by events.

Martin Luther was in some ways a medieval man, taking for granted that the monastic life was the highest way of living the Christian life and entering a monastery after making an impulsive vow of the kind at which Erasmus would have scoffed. Like so many at the time, he was educated by the Brethren of the Common Life. He translated the New Testament into German using Erasmus's Greek edition, but he was not himself a Humanist and was convinced that Scholastic theology was more Aristotle than Christ. The late medieval religious crisis affected him through his education in Nominalist theology and his reading of Tauler and the German Theology, all of which gave him a sense of the overwhelming greatness of God. He recoiled from a piety that rendered God accessible to human effort.

Struggling to be a good monk, he was nonetheless almost paralyzed by the conviction that, despite his best efforts, he was damned. The crisis was resolved in his "tower experience," when for the first time he understood "The just man lives by faith" to mean salvation by faith alone, by trust in the saving actions of Christ.

Luther's preoccupation with his own salvation had precluded his playing a public role. But his sudden breakthrough in understanding justification convinced him that the Catholic Church had failed in its most basic task—it could not offer a sure road to salvation, because it gave people a false sense of their own merits, based on "good works." Although the Church was viewed by many people as oppressive, Luther in one sense accused it of being too easygoing, of falsely assuring people of salvation and thereby short-circuiting their repentance.

An explosion followed the Ninety-Five Theses because, while indulgences did not rank near the top of any list of Catholic doctrines, many things came together around them—anxiety about personal salvation, the credibility of official teaching, the significance of routine acts, the rapaciousness of some of the clergy, and the apparent sale of a spiritual good. Luther may or may not have posted the Theses on a church door, but he made them public after encountering ordinary people who displayed their indulgence certificates. Without quite saying so, Luther seemed to deny the efficacy of indulgences altogether and even the existence of Purgatory. The Vatican tried both the carrot and the stick to gain a retraction from him.

Luther's decisive break with the Catholic Church occurred at the Leipzig Debate in 1519, when the theologian Johann Eck demonstrated that indulgences were official Catholic teaching, forcing Luther to appeal first from the pope to a general council, then from a council to Scripture, proclaiming that the Bible alone was the locus of authority.

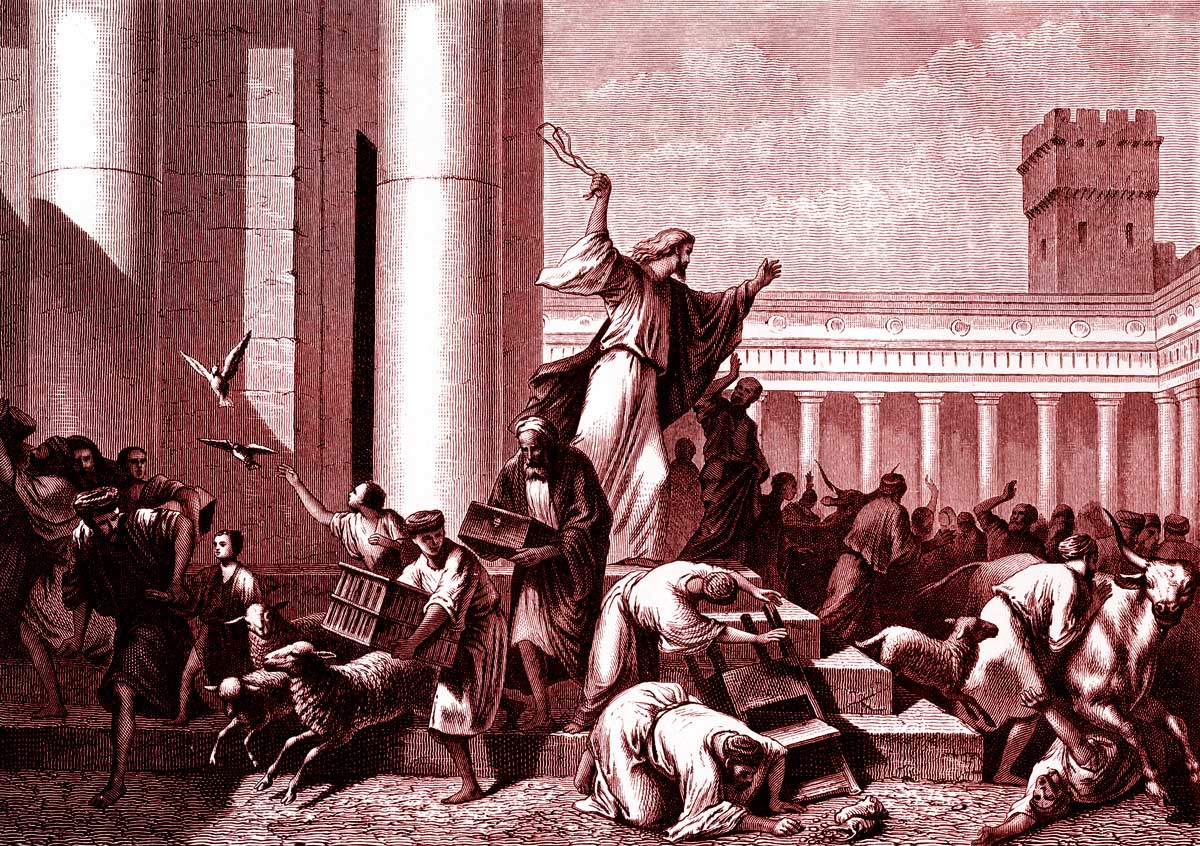

Luther did not set out to be revolutionary. But logically, if the Church had erred on the crucial matter of salvation, none of its doctrines were credible. The stakes were as high as they possibly could be. Leo condemned Luther ("a wild boar is loose in the vineyards of the Church"), and Luther publicly burnt the papal bull and the Code of Canon Law. In a great rush, Luther then began systematically measuring Catholic teachings against the Scripture, rejecting almost the entire Catholic system—the authority of popes and bishops, five of the seven sacraments, the Mass, Purgatory, the invocation of the saints, monastic vows, and many other things.

Other Evangelical Figures

The term "Evangelical" encompassed numerous people who sought the truth in the Scriptures. But as the list of disputed doctrines got longer, some Evangelicals remained Catholics, others broke with the Church, and for a time there was an uncertain middle group who still hoped for a peaceful resolution. The French bishop Guillaume Briconnet briefly made his diocese a center of pastoral Evangelicalism, harboring both Lefevre and several people who became Protestants, including Guillaume Farel, John Calvin's predecessor at Geneva.

Like Lefevre, Erasmus remained a Catholic, seeing peace and charity as the hallmarks of a true Christian and the unity of the Church as paramount. At first he congratulated Luther, because indulgences were an example of what Erasmus considered superstition, but he was increasingly troubled at what he thought was Luther's heedless divisiveness and his dogmatic denial of free will. (To the degree that Humanism implied a positive valuation of human nature, Luther and Calvin represented the final rejection of the Renaissance.)

Whatever Wessel Gansfort himself might have intended, Luther praised him as a precursor. Reuchlin, although most of his students became Protestants, remained a Catholic and was even ordained a priest. The skeptical Conrad Celtis was condemned posthumously by both Catholics and Protestants. Willibald Pirckheimer was a Humanist and a friend of both Erasmus and Luther who demanded that the Mass be said in the vernacular and that communion be given to the laity in both kinds. But he opposed the introduction of the Reformation in Nuremberg, and he defended monasticism.

If the Reformation had not been set off by Luther in 1517, it would have occurred in Zurich a few years later. Ulrich Zwingli was a parish priest some of whose parishioners defied church law by eating sausages on Ash Wednesday. This incident provoked a crisis of authority that, as often happened at the time, was settled by the town government. Zwingli's leadership was officially accepted, so that, in effect, Zurich left the Catholic Church.

Calvin was a Frenchman who, unusual among Reformation leaders, was a layman, trained as a Humanist and a lawyer. In Paris he was involved with an Evangelical group connected to Lefevre, most of whose members fled the city under suspicion of heresy. In a way, Calvin's doctrine of predestination was the culmination of the long-simmering complaint that the Catholic Church had made God too accessible to man.

Slow-Moving Catholics

Catholics were somewhat slow in mounting a defense, partly because Catholic apologists were reluctant to write in the vernacular or use the printing press, lest it seem that doctrine was being submitted to popular judgment. Their formal Scholastic style was also not effective against the very blunt rhetoric of Luther and others.

The doctrine of "sola scriptura" struck at the heart of the Church's authority and forced a clarification of Catholic beliefs. At issue was Christ's promise to be with his Church always and the continued presence of the Holy Spirit, therefore the authority of doctrines and practices not found explicitly in the Bible but unfolding over time. Since the Church itself had determined the canonical text of the Scripture, it was impossible to set the Bible over the Church. Eck, for example, located Revelation in the "living Church," guided by the Holy Spirit, in contrast to a written Scripture that, if divorced from the believing community, was dead.

Henry VIII was at first a militant Catholic who wrote The Defense of the Seven Sacraments to refute Luther, arguing that Scripture was an inadequate guide to truth and defending the sacraments on the basis of papal authority.

Thomas More—who was commissioned by the English bishops to refute William Tyndale—was perhaps the first Erasmian Humanist to recognize clearly what was at stake. He asserted that it was not essential that believers read the Bible, so long as the Church interpreted it for them. (The first Catholic edition of the Bible in English—the Douai-Rheims translation—predated the King James Bible but appeared long after Tyndale's translation.)

Issues Battled Over

The religious battle was fought on the basis of history as well as theology. More was something of a Conciliarist and said little about the papal office. He did not make a strictly theological argument but extolled Catholicism as an entire way of life, including some things (the veneration of relics) of which he and other Humanists had previously been critical. Cardinal Caesar Baronius attempted in his Annals to show that, contrary to the Protestant Magdeburg Centuries, the Catholic Church had preserved an unbroken tradition.

Deep theological issues probably passed over most people's heads in the sixteenth century, while practical matters like indulgences and fast laws were flash points. For most people, faith was understood primarily as piety—Marian devotions, the cults of the saints, prayers for the dead, pilgrimages, the veneration of relics, indulgences. If these things made the Church vulnerable to the charge of superstition, they were also anchors of many people's faith. Thus, the abolition of indulgences, the closing of shrines and monasteries, the destruction of images and relics, and dramatic changes in the liturgy sometimes aroused armed popular resistance. The subtle doctrine of the Real Presence was a major issue, and it had a crucial practical dimension in people's kneeling or refusing to kneel as the sacrament passed in procession.

But the sharpest issues were those, like indulgences, that directly affected eternal salvation. Thus, the saints were no longer to be regarded as intercessors, and their shrines were destroyed. The leading Reformers continued to hold that Mary was the Mother of God and a perpetual virgin, but they were so determined to obliterate every trace of what they considered superstition that the figure of Mary almost disappeared from Protestant consciousness. Images provoked violent passions, as iconoclasts outraged traditionalists by destroying the "idols" that had long been an embodiment of the sacred.

Monasteries served as destinations for pilgrims, hostels for travelers, and centers of charity for the sick and poor; thus, their dissolution excised institutions that had sometimes been an integral part of the local community for over a thousand years.

It was perhaps the denial of Purgatory that affected people most deeply, since it seemed to cut them off from their ancestors, while the doctrine of predestination seemed to offer sinful people no alternative to hell.

Luther and Zwingli's disagreement over the meaning of "This is my body" showed that, contrary to what Luther had thought, sola scriptura would not lead to consensus. From the beginning, the leading Reformers had to invoke some kind of church authority against the free interpretation of Scripture, so that Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, and others came to be called the Magisterial Reformers, because they upheld the historic creeds and the early ecumenical councils. Despite hostility to Scholastic theology, some Protestants began to theologize in the Scholastic mode, as in the Lutheran formula of "consubstantiation," in order to clarify disputed questions.

First Zwingli, then Luther, had to confront "zealots" who among other things denied infant baptism, from which point there was a widening circle of radical ideas. Both Catholics and the Magisterial leaders expelled "Anabaptists" from their cities and often put them to death.

Ties Between Religion & Politics

Except among the radicals, the ties between religion and politics were pulled even tighter throughout the sixteenth century. The papacy had its own territorial interests, and bishops were often secular as well as spiritual lords. Ultimately, the success or failure of the Reformation in particular areas was due almost entirely to its rulers.

The German Emperor Charles V at one point offered Lutherans clerical marriage and communion in both kinds, an offer they rejected as too little, even as Pope Clement VII rejected it as the emperor's unwarranted assumption of ecclesiastical authority.

Luther urged the princes to undertake the forcible reform of the Church, if the clergy would not, charging that its great wealth had been stolen from gullible Germans. Some bishops and abbots accepted his invitation.

But Lutheranism was almost dealt a fatal blow by the massive Peasants' Revolt of 1524–1525, when thousands of poor farmers rose up against their lords. A manifesto issued by the rebels cited Luther's words about Christian freedom as justification for their actions, and when they cited his response as yet further vindication, he condemned them in the strongest terms.

"Anabaptism" manifested a potential for anarchy when a group of sectarians seized control of the city of Munster and acted out an antinomian nightmare, putting their opponents to death, proclaiming their leader to be a divinely ordained king, and requiring promiscuous sexuality.

Although all rulers believed they had a divine obligation to uphold the truth, the right of subjects to rebel, even including the right to assassinate a "tyrant," was asserted by some Calvinists and Jesuits. Luther was uncertain about the right of rebellion.

Charles V avoided as long as possible the inevitable civil war that would erupt if he attempted to move against the Lutherans. (The word "Protestant" was originally applied not to theological dissent but to those who protested Charles V's announced intention of doing so.) When he finally made his move, the war was a stalemate, and the Peace of Augsburg, signed in 1555, was the first official recognition of religious tolerance in European history ("cujus regio ejus religio"—"whose rule, his religion").

From Geneva, Calvin sent clergy back to France, where they made converts among both the aristocracy and the merchant class. (For unknown reasons, the French Calvinists came to be called Huguenots.) After a time, Catholics and Huguenots began committing acts of violence against each other, which escalated into a civil war that lasted for most of the rest of the century and in which it was impossible to separate religion from dynastic rivalries.

Eventually the Huguenot Henry of Bourbon successfully claimed the throne as Henry IV, announcing his conversion to Catholicism but issuing the Edict of Nantes in 1598, which gave the Huguenots limited freedom of worship. (He was assassinated by a Catholic fanatic.)

In England a rapid series of religious changes were almost entirely acts of state. Henry VIII's claim to be head of the Church renewed an old issue—whether the king could be truly supreme in his own kingdom if the Church possessed a higher moral authority. (Thomas More was executed for failing to affirm royal supremacy.) England then went through three rapid religious changes under each of Henry's children—the Protestant Edward VI, the Catholic Mary I, and the Protestant Elizabeth I. Philip II of Spain (Mary's widower) launched his Great Armada against England with the aim of deposing Elizabeth in accord with a papal bull, but the fleet was routed.

As in France, Calvinism in Scotland showed a willingness to oppose royal power in the name of religion. Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots, was driven out and was later executed in England by her cousin Elizabeth.

The Netherlands—a territory that had a majority of Catholics, with significant Lutheran, Anabaptist, Jewish, and Calvinist elements—remained under the rule of Spain. Philip II's attempt to suppress religious dissent galvanized massive resistance, leaving Spain in control of only the southern provinces that would eventually become Belgium. The United Provinces of the North retained a formal policy of religious toleration but were increasingly dominated by Calvinists.

Although Poland is usually thought of as a Catholic country, there was a significant Protestant presence there, it being a place of refuge for sectarians not welcome even in Lutheran and Calvinist lands. Although Hungary, too, is usually thought of as Catholic, part of it was under Muslim rule, and there was a significant Calvinist presence.

Whereas Luther created a territorial church controlled by the princes, Calvin created a semi-autonomous church that had a somewhat uneasy relationship with the city government but in which law was supposed to be in close conformity to the gospel. Calvinism's presbyterian ecclesiastical structure fit well with republican civil governments, but Calvinism also appealed to feudal nobles.

Conversely, although Calvinism had a special appeal to the commercial middle class, the Catholic merchants of Italy saw no need to change religions. Both Calvin and some Catholic moralists offered cautious justification for the profit motive and for usury, although Luther did not. In Protestant countries, the abolition of monasticism implied that poverty no longer had positive value and was to be eliminated by one means or another.

Protestants and Catholics differed little over practical moral questions like divorce and contraception. But Catholics, Anglicans, and Lutherans tended to tolerate prostitution, dancing, gambling, and drunkenness as sins that could be restrained but not suppressed. Calvinists condemned almost all aspects of popular religious culture—its art and music, pious practices, and communal celebrations such as fairs and carnivals.

Lead-Up to Trent

The reform of the papacy was long in coming. The popes in the period from the Council of Constance to Lateran V were among the worst, although in an ironic way Alexander VI testified to the continuing power of faith, in that he was not a cynic but a believer whose conscience was troubled by his sins.

The austere ways of the reformer Adrian VI—a Netherlander who had been the tutor of Charles V and yet another student of the Brethren of the Common Life—made him unpopular with the cardinals during his very brief pontificate. Clement VII, like his cousin Leo X, proved unable to deal with the crisis.

Papal support for the reforming impulse began with Paul III, who had led a scandalous life but underwent a change of heart. Paul named Contarini, Caraffa, Pole, and other reformers to a Commission for the Reform of the Church, the result of which was a blunt diagnosis of evils and how they were to be corrected, not sparing the papacy itself.

But the spread of Protestantism placed the Spirituals in an awkward position, since the doctrine of justification was now considered the principal issue. Contarini met Lutheran theologian Philip Melanchthon at the Regensburg Conference of 1541, where the two agreed on the nature of justification. But there proved to be no meeting of the minds on the ecclesial issues—the priesthood, the Mass, the sacraments, and papal authority. The Spirituals also suffered acute embarrassment when Bernardino Ochino, the third general of the Capuchins and a preacher of reform, fled from Italy and eventually ended up on the left wing of the Reformation. Several other leading Italian prelates did the same.

Cries for another general council began almost as soon as Lateran V ended in 1517. But there were formidable issues: whether Lutherans should participate; whether the council should be fully under papal authority or be semi-independent, in accord with Conciliar theory; the degree to which secular rulers would exert influence. Not until 1545 were the obstacles overcome sufficiently to enable Paul III to summon a council at Trent. For political reasons France boycotted the proceedings, thereby leaving the Italian bishops as the large majority, along with some Spanish and Germans and a smattering of others.

Doctrine & Discipline

The differences between Spirituals and Zealots led the council to consider disciplinary and doctrinal issues simultaneously, both correcting abuses and clarifying doctrine. The root of abuses was bishops' neglect of their dioceses, so Trent required episcopal residence, abolished pluralism, and forbade nepotism. Each diocese was to establish a seminary where candidates for ordination could be properly formed. On the doctrinal side, Trent authorized the first comprehensive catechism of Catholic doctrine, an idea borrowed from Luther. The council condemned heretical propositions but did not attribute them to anyone by name.

The nub of all theological issues was the nature of authority. The council affirmed the authority of the Vulgate and affirmed "unwritten tradition" as a source of truth along with the Bible, the authenticity of Tradition being guaranteed by the Holy Spirit.

As at Regensburg, the issue of justification was recognized as the heart of the theological conflict, the opposing errors being, on the one hand, the denial of good works, and on the other, a Pelagian optimism about human nature. All sides appealed to the authority of Augustine. The definition was subtle. Human beings stood condemned because of Original Sin and were saved only by the sacrifice of Christ. They had to respond freely to the offer of salvation, but that response was made possible only by "predisposing grace," which was offered to all, without any merit on their part. Once accepted, such grace rendered human works meritorious in God's sight. The council reaffirmed indulgences but decreed that their reception should not be tied to any monetary payment.

On disputed disciplinary issues, priestly celibacy was reaffirmed; Christ was declared to be present "whole and entire" under both Eucharistic species, so that it was not necessary to receive communion under both kinds and laymen were not permitted to do so; and the celebration of Mass in the vernacular was forbidden.

Paul IV, who as Cardinal Caraffa had set up the Roman Inquisition, as pope established the Index of Forbidden Books. He enforced clerical good conduct by imprisonment or exile and imposed draconian laws on Rome.

The key to reform at the local level was a zealous bishop, of whom Charles Borromeo of Milan was the model. He led an austere life, visited plague victims, and relentlessly strove to reform his clergy, causing some Franciscans to attempt to assassinate him as he presided at vespers.

Francis Borgia was a Spanish duke who joined the Jesuits and became a saint and Ignatius's second successor as general of the Society. He was the great-grandson of the wicked Alexander VI and the grandson of an archbishop.

Art & Mysticism

For uncertain reasons, as art and architecture experienced some of their greatest flourishings in the Italian Renaissance, the culture of the North found it increasingly difficult to see spiritual meaning in material things. The Modern Devotion, mysticism, and other things all looked inward. (The question of "externals" also divided some of the Reformers, with Lutherans and Anglicans accepting adiaphora, "things indifferent," so long as the Bible did not explicitly forbid them.)

Zwinglians and Calvinists smashed statues and stained-glass windows, whitewashed the walls of churches, and allowed no music except the unaccompanied chanting of Psalms. Biblical scenes were practically the only acceptable form of Protestant art, although even they were not permitted in churches. (In this, as in other things, Luther proved to be the most conservative of the Reformers.)

If part of the Protestant critique of Catholicism was that it fostered mere rote piety, the Church of the Catholic Reformation assiduously cultivated interiority. There was a second flowering of mysticism, this time in fervently Catholic Spain, without suspicion of heresy. Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross were practical reformers as well as mystics, and they insisted on complete adherence to the teachings of the Church. Teresa described how, after passing through many stages, the soul finally achieved the fulfillment of its longing for God, an ecstasy in which she was set on fire by her Bridegroom's all-consuming love. John of the Cross identified The Dark Night of the Soul—the sense of utter abandonment that the soul experienced as it was being led into the highest realms of spiritual union.

Loyola, too, had mystical experiences, but Jesuit spirituality was forged primarily for people in the world. The Spiritual Exercises were rigorous and systematic, embodying a shrewd understanding of human psychology, and proceeding step by step until the individual could assess how he could best promote the greater glory of God.

Catholic sacramentalism inspired a dazzling new artistic style called the Baroque (a term of uncertain origin), which became the preeminent art of the Catholic Reformation, uniting doctrinal orthodoxy with dramatic expression. The Baroque expressed a restless spirit, its palpable tensions suited to manifesting the dramatic struggle to subdue the will. It also expressed the Catholic affirmation of free will and the efficacy of good works, as well as a longing for infinity. The path to heaven was a strenuous one, but glorious rewards were visible to those who struggled. As the Baroque style developed, it became the vehicle of Catholic triumph, celebrating an admittedly partial victory over Protestantism and a successful reassertion of the Church's spiritual authority.

Fruitful Reform, Shattered Christendom

In 1626, Pope Urban VIII officially opened St. Peter's Basilica, almost every detail of which proclaimed a faith that had survived its greatest crisis—the papal throne and the giant statue of St. Peter reaffirming papal authority, the pillars around the high altar serving as huge reliquaries, the wide panoply of intercessory saints overlooking St. Peter's Square. Ironically, the dedication of St. Peter's marked the successful completion of a project whose beginning—the indulgence preached in order to finance it—had triggered an endless series of events that had almost been fatal to the Catholic Church.

The spirit of the Catholic Reformation, forged at Trent, was one of strict orthodoxy and morality, deep personal piety, and obedience to Church authority, a revival that was profoundly successful in giving the Catholic Church a character that would endure for four hundred years. In many ways the essence of Protestant reform was an austere simplicity—the closest possible adherence to Scripture without distraction and, in effect, the forging of a new psychology quite different from that of the Middle Ages.

There were many movements for reform in the period 1300–1600, all of which bore fruit in significant ways. Tragically, in the end, their very successes left Christendom shattered.

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on protestant from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor