View

The Unforgotten

Casey Chalk on Costly Grace in Breece D'J Pancake's Flyover Country

In a time of heightened interest in America's white working-class culture—long overlooked by the media and meritocratic elites—people are turning to "redneck" representatives like J. D. Vance, whose national bestseller, Hillbilly Elegy, has been trumpeted as a trenchantly poignant survey of Rust Belt and Appalachian life. Such national introspection related to this long-ignored demographic is justified, though much of the public conversation has centered on contemporary voices rather than more historical representatives. The latter, however, can help explain how we have reached this particular socio-cultural moment.

A good place to start would be with West Virginia author and verified hillbilly Breece D'J Pancake, whom Kurt Vonnegut declared "merely the best writer, the most sincere writer I've ever read," and whose writing has been compared to that of James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. Pancake's fiction is hauntingly prescient in its reliance on themes so relevant to contemplating America's "flyover country." Written a decade before Vance was born, his work—comprising only a dozen short stories—touches on the themes he witnessed as a native of rural Appalachia: poverty, isolation, violence, and the ensuing feeling of dispossession that leads so many of its working-class inhabitants to descend into the fleeting tourniquets of alcoholism, drug use, and sexual promiscuity.

Not only is Pancake prophetic, but he is also powerful in his exploration of moral and spiritual themes peculiarly germane to our times. Hidden within the often grim and desolate world of 1970s West Virginia is a persevering, if often unspoken, trust in a God whose grace appears both frustratingly distant and inexplicably imminent. It is a costly grace, felt amid the shipwreck of lives ruined by men's own bad decisions as well as by the inexorable pressure of socio-economic forces beyond their control. These themes are showcased not only in Pancake's puissant prose, but also in his own unfortunately abbreviated life.

Pancake's Life

Breece Dexter John Pancake, born in 1952, was raised in rural West Virginia and attended Marshall University in Huntington, where he completed a degree in English. He briefly taught at a couple of Virginia military academies, and enrolled in a creative writing program at the University of Virginia (UVA). It was there that he wrote most of his published stories, several of which appeared in The Atlantic. It was there also that he received the misspelling of his middle names, "D'J," which he would amusedly adopt. His last name, which is just as arresting, is a literal translation of Pfannkuchen, the German word for "pancake." A likely successful writing career was cut short by his unexpected suicide outside of Charlottesville in 1979.

Pancake was a true—and proud—hick, an identity that he likely over-emphasized at "Mr. Jefferson's university," where southern aristocratic families still send their boys to receive educational and societal grooming. He hiked, hunted, and fished in the Blue Ridge Mountains, and he loved to play pool and drink beer. As author and friend John Casey described him, "he looked like one who'd done some hard work outdoors." He maintained a fairly significant cache of firearms. He was a "good union man," who sought to improve the post-graduate professional opportunities of his fellow graduate students.

Pancake also knew "the bitterness and romantic longing of the wounded, fearful and superfluous man," as a 2014 review in The Guardian observed. His father, an alcoholic, died of complications from multiple sclerosis in 1975. Three weeks later, his closest friend was killed in an automobile accident. And in 1977, his girlfriend bowed to pressure from her well-to-do family and rebuffed Pancake's marriage proposal. Like many of the male characters in his stories, Pancake dated aspirationally, courting women above his own class. "Her parents have decided I'm not good enough for her," he wrote to his mother after the rejection.

Pancake had a zealous, if complicated, relationship with Christianity. He converted to Catholicism in his mid-twenties and became active in UVA's parish church, exhibiting an often off-putting zeal for the faith. John Casey noted that his role as Pancake's godfather soon "turned upside down," with the convert lecturing him on his lackluster commitment to the Mass, the sacrament of confession, and raising his kids Catholic. "He took in his faith with intensity, almost as if he had a different, deeper measure of time," Casey said. "He was soon an older Catholic than I was." One of Pancake's favorite quotations was the notoriously severe language of Revelation 3:15–16: "I know thy works, that thou art neither cold nor hot: I would thou wert cold or hot. So then because thou art lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew thee out of my mouth."

It is thus not surprising that Pancake donated to the church the $750 he received from The Atlantic for his short story "Trilobites." But despite these demonstrations of piety, he wrestled with submitting his flesh to his newfound faith. Friends at UVA remembered his inclination towards violence, exemplified in his bragging about scars he received from fights in lower-class bars outside the more genteel confines of Charlottesville. He was serially promiscuous, a vice made worse by his vocal condemnations of women he viewed as too willing to offer him their bodies. He also wrote to friends of a desire to end his life, telling one that if he weren't such a good Catholic, he would kill himself.

Aspiration & Devotion

The treatment of God and Christianity in Pancake's stories is similarly tempestuous, a fact largely overlooked in reviews of his work that have focused on the themes of societal and economic change and the sense of isolation and powerlessness that inevitably follows. Indeed, the central dilemma in Pancake's small corpus invariably involves male characters struggling in the backwaters of Appalachia, trying to determine how they will respond to the decline of their way of life.

These isolated, discarded men are torn between aspirations for something beyond their meager lot and a firmly rooted cultural devotion to family and community, an identity they might very well forfeit if they leave their ancestral lands. Author Andre Dubus III (House of Sand and Fog) notes that in each story, "there is a gun and whiskey and a craving for a change of almost any kind." Yet grace—in both its obscurity and its surprising interventions—is one of the most consistent and important themes in Pancake's work.

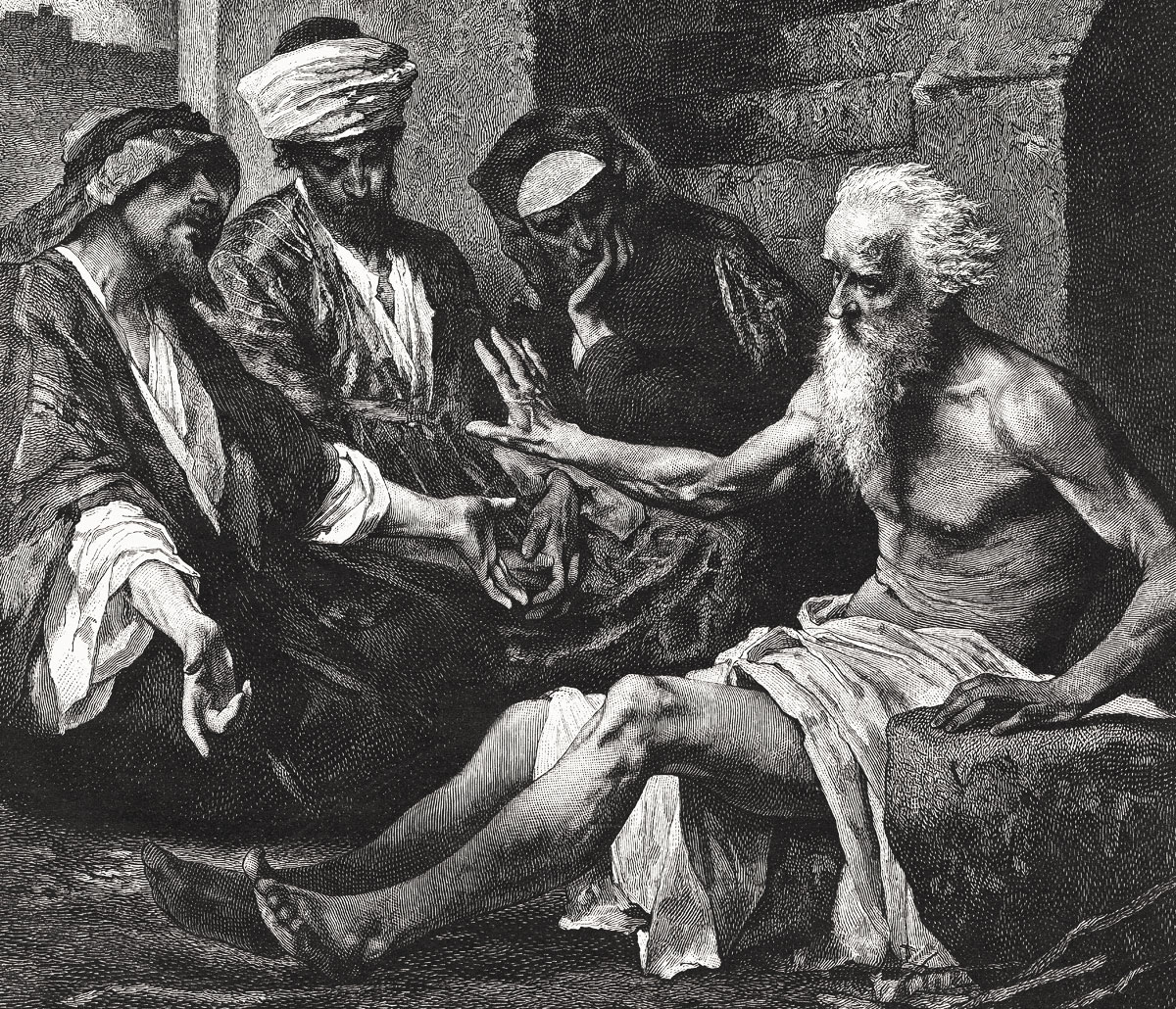

Take "First Day of Winter," the tale of Hollis, a poor West Virginia boy serving as caretaker for his elderly parents while "fighting a losing battle" with the family's unprofitable farm. Hollis is at odds with his more prosperous brother Jake, a pastor in Harpers Ferry, over their parents' future. In an ironic reversal of roles, it is the parson who argues for placing the elderly couple into a home. Hollis answers that he will not have them "put away like furniture," and warns that they will be starved, mistreated, and ultimately "smothered" in a home. On Thanksgiving Day, while out hunting squirrels on behalf of his blind father, a weary Hollis, already tormented by his failing financial fortunes, feels a sudden "darkness" covering him as he finds himself momentarily pondering his parents' deaths. Surprised and terrified by his morbid musings, he hurries back to the house, where a somber mood prevails over the evening. Hollis confesses—much to his father's ire—that he had earlier asked his brother to take them in.

At first glance, God seems quite distant as these sorry figures contemplate a diminishing subsistence. But is he? As a forlorn Hollis sleeps "in the graying light," his mother hums a hymn, while the vale is as quiet "as an hour of prayer." Their prospects may be as "brittle, open, and dead," as this first day of winter, but as the family members rest, they retain a still-tangible quiescent trust in divine providence, and a stubborn, ineradicable moral rectitude even in the most fatal of circumstances, evinced by Hollis's refusal to abandon his parents.

In this, as in all his stories, Pancake exhibits an acute ability to portray each character, as well as the Appalachian landscape, in memorably raw and intimate details that hint that someone—God?—is keenly aware of even the poorest, most forgotten hollow of West Virginia. Grace abides in the void. Dubus characterizes this as a "constant striving for goodness up against the seductive pull of the darkness. . . . [Pancake's] writing reflects the eternal human needs to love and be loved, our unavoidable fallibility, and our eternal yearning for grace."

Impenetrable Workings of Grace

Another story with a potent, if latent, spiritual message is "The Salvation of Me," in which a teenage boy describes a series of unexpected blessings as "weird stuff [that] started happening." His widower father finds religion, stops drinking, and begins attending a Methodist church twice on Sundays. The cynical teen in turn finds an unprecedented inner strength to study harder, improving his grades and eliciting the attention of his boss, who offers to be his college sponsor. He begins attending Catholic catechism classes. He dates the daughter of the town's deputy police chief, and when she becomes pregnant, the two marry.

Then, just as quickly, the girl loses the child, the marriage is annulled, dad is back to drinking, and the protagonist has lost interest in post-secondary education. In a cruel twist of fate, his best friend from high school makes it big on Broadway, returns to town, and pretends not to known him. The story ends with the main character once again alone, all of his aspirations for a better life seemingly fruitless.

In this world, disfavor and depreciation come just as unexpectedly—yet seemingly inevitably—as do the moments of apparent divine favor. There is a gritty and praiseworthy accuracy to Pancake's melancholic portrayal of the impenetrable workings of grace in everyday life. To borrow Dietrich Bonhoeffer's phrase, grace is never cheap, but is commensurate with a broken and contrite heart weary with one's own sins.

A channel of longsuffering faith and an abiding perseverance amid pain runs through Pancake's work. It is the quiet, unspoken piety informed by family, tradition, and duty that seems to enable his protagonists to persevere. Such seemingly intractable qualities characterize generations of Scotch-Irish immigrants in Appalachia and the Rust Belt. Grace and faith are there, amid these shadowlands, though their effects are only fleetingly perceived.

Perseverance & Providence

Something even more powerfully perceived in his dramatic portraits of hard-up men and women is the fact that Pancake himself truly loves these characters, with all their follies and insecurities. Indeed, his prose exhibits a profound and sincere empathy for (and defense of) the workingman's way of life, and his protagonists serve as literary manifestations of the kind of American most marginalized by the forces of globalism and multiculturalism. The more these characters suffer and fail, the more we are drawn to love them.

These stories represent an appreciation for Bonhoeffer's costly grace: "the treasure hidden in the field . . . the pearl of great price to buy which the merchant will sell all his goods. . . . Such grace is costly because it calls us to follow, and it is grace because it calls us to follow Jesus Christ." This grace is hidden amid the grim melancholy of the stories of Breece D'J Pancake, whose characters' most pervasive and appealing quality is their stubborn perseverance as they find ways to survive, to laugh, and even to love in spite of every misfortune. One could credit such tenacity to a certain ineradicable gene in the Scotch-Irish bloodline, or to a working-class ethosthat expects (and even subsists) on hardship and failure.

There is another factor, however, that I think (or hope) to be just as indelible. It is a firmly ingrained trust in providence and God's sovereignty, if only discerned in the still quiet voice heard by Elijah, or the silent yet perceptible calling of Esther. It is in that faint, unspeakable mystical communion of the heart with its source, often felt with the last rays of a cold winter sun, that we are called to return to "our first love" (Rev. 2:4), the one so routinely forgotten and so easily overlooked.

Casey Chalk is a graduate of UVA and a student at the Notre Dame Graduate School of Theology at Christendom College, Front Royal, Virginia. He is also an editor for the ecumenical website Called to Communion (www.calledtocommunion.com)

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor