View

Letter to My Students

Preston Jones on a Charge to Keep Before It's Too Late

Dear Students: I will tell you about two key moments in my life. They came close together. I think I was seventeen. I'm not sure which came first.

One came during a time of prayer in my room at home. I don't know what I was praying about, but I do know that I walked out of my room with a powerful sense of life's brevity—a strong sense that time was slipping away and that if I were to accomplish anything in life, then I would need to get busy. That feeling has never left me.

The second moment came during the first day of a high-school class taught by Mr. Charles Grande. The class came in a season when I regularly went to school. Periodically since the eighth grade I had attended classes only when I felt like it, sometimes skipping school for multiple days. School seemed like a vast waste of time, and the neighborhood I had to walk through to get there was dangerous. So I often stayed home and read books, though I had no one to talk with about them.

Mr. Grande was serious in a way no other teacher was. I didn't know the Latin word gravitas at the time, but he embodied it. On the first day of class, his vocabulary was more suited for students at a selective college than for the apathetic herd then facing him. Yet he wasn't trying to impress anyone. He was saying, I think we can do better than we're doing.

It was obvious that he believed in what he was doing. This wasn't related so much to the class's subject matter as it was to a clear, deep commitment to the cause of learning. Perhaps most impressive of all, he said that he wanted to learn from us, and we believed him. He made no attempt to be any student's special friend; he didn't bother much about being liked. But we all knew that he cared about what he was doing. For the first time, I felt that my mind might have a purpose. Before the year was up, I learned that Mr. Grande was a Christian.

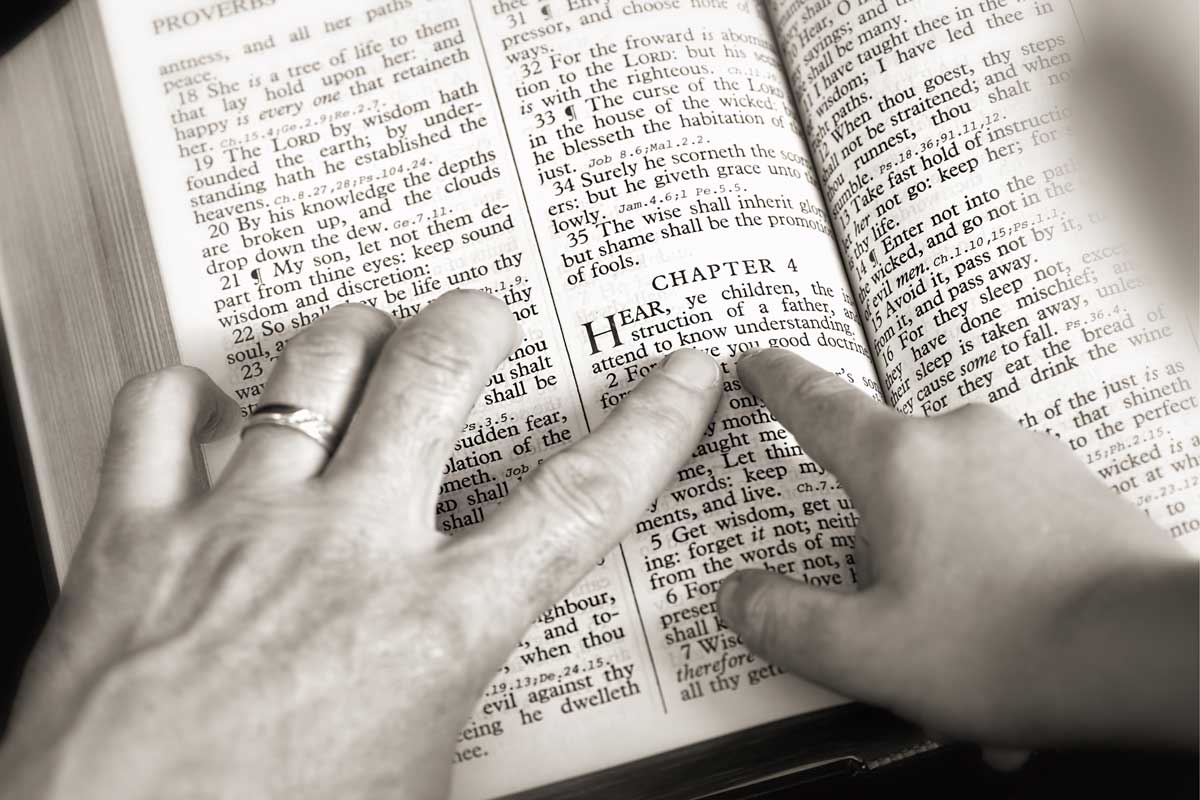

The effects of these two moments converged. I was now preoccupied with the never-ending, always--pressing passage of time, and Mr. Grande showed me how to channel that energy. His commitment became my commitment. The kid who sat slumped and uninvolved in the back of the class (when he actually went to class) was now reading Tolstoy, Shakespeare, Martin Luther King, Albert Camus, and books by the Christian philosopher Francis Schaeffer. I didn't understand much at the time, but when I flip through the pages of the books I read back then, as I sometimes do, and see the notes I wrote in the margins, I remember a kid who was, as Mr. Grande would say, "working on it."

Most people will have no difficulty understanding why meeting Mr. Grande was important. A kid's potential was tapped. A teacher had not only done his job but had left a lifelong mark. I go further. As I once said to a waitress at a restaurant where I took Mr. Grande, then in his eighties, for lunch: This is Mr. Charles Grande. He was a teacher of mine, and he saved my life.

But the constant, powerful sense of time's passage and of life's brevity—this is not something many would consider a gift. A culture that so often rehearses nonsense like "It's never too late" simply doesn't want to acknowledge some of the precepts that Western civilization's most enduring philosophers, as well as the New Testament, have offered for consideration: that time is always running out, that a person's life is an always diminishing resource, and that, in this life, it is constantly too late. Stupid things said can't be unsaid; it's too late. The voluntary degradation of oneself and others can't be undone; it's too late. The character I have created as a result of myriad small decisions cannot easily be exchanged for another.

One doesn't have to be a great sociologist to notice that American society is not much informed by a sense that time is short and that the squandering of a precious, ever-diminishing resource—one's own life—is calamitous folly. Certainly Mr. Grande understood this. He talked about having "only" ten years left to teach, as if the end of his career were just around the corner. He ended up teaching another fifteen years, but I'm sure the time flew.

I will mention another moment. This one came about thirty years after the other two. I was at a funeral for someone who had died unexpectedly. A young woman rose to give a eulogy. It was clear that she wanted to say something important, something befitting the heavy occasion. But as she spoke, it became clear that she had nothing to say, less for sorrow than for a simple lack of resources. The library shelves of her soul were empty. She cobbled together a string of clichés and catchphrases and ended with a quotation from a TV show. The sadness of the event was compounded by the need for profundity going unmet.

Preston Jones teaches history at John Brown University.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor