Feature

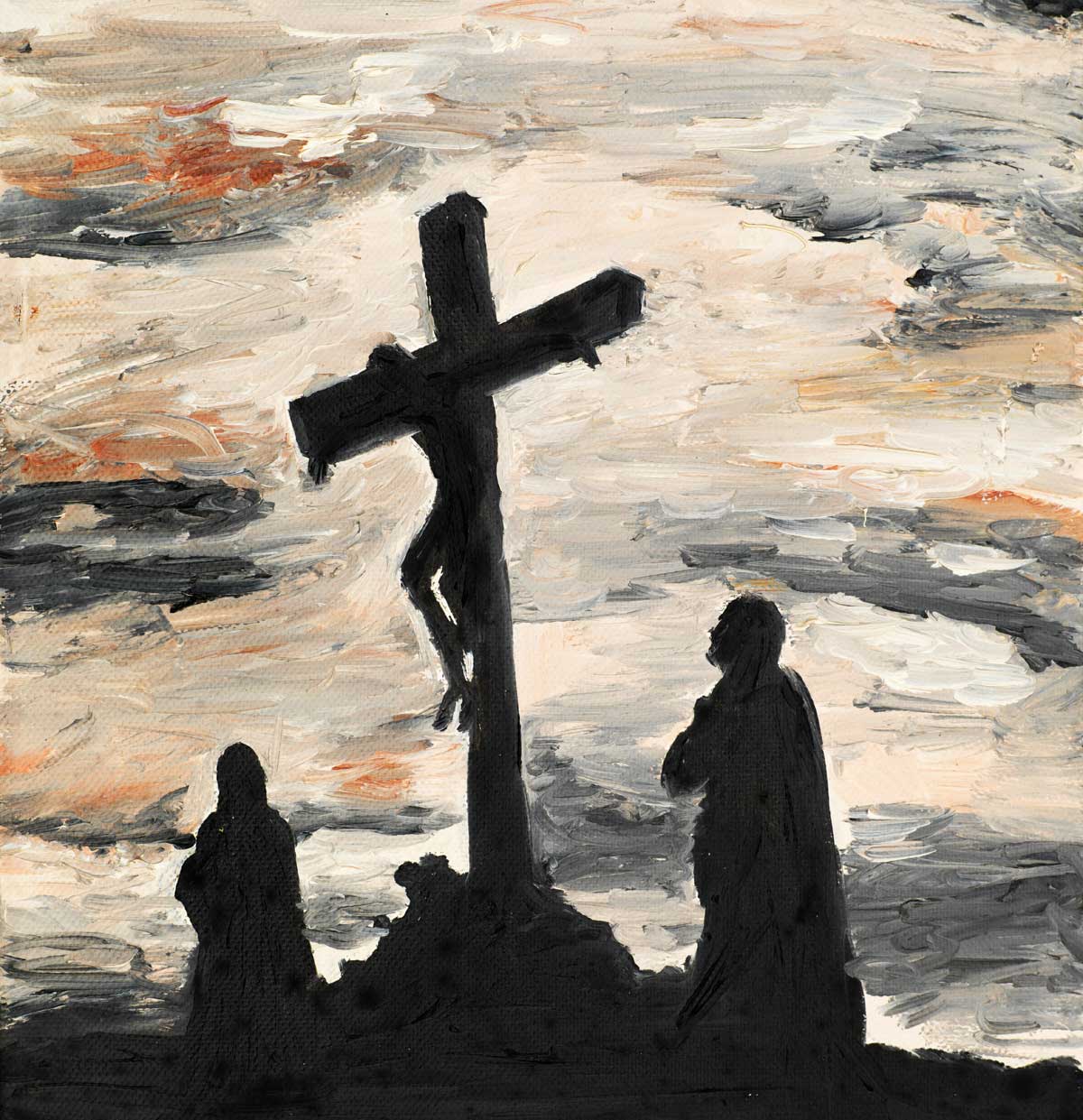

The Cross of Least Resistance

Our Path to Holiness Runs Straight Through Calvary

I think I might stop being a Christian," my friend said, a few minutes after comfortably situating himself in my office.

"Why?" I asked. "Have you stopped believing in God?"

My friend, whom we will call Trevor, pondered silently. A few days before, he had asked to meet me to get some advice about a personal crisis he was facing. But the conversation quickly turned to his more general struggles with Christianity.

I renewed my question: "Is it because you've stopped believing in God that you are considering giving up Christianity?"

"It's not that, Robin. I still believe in God. But I've been at this Christianity thing for over six years now, yet I'm still struggling with the same sins and addictions as when I converted. People keep telling me I need to rely on the Holy Spirit to help me, but however much I pray and ask for help, it never gets any easier. I just can't achieve victory over the sins in my life. Why isn't the Holy Spirit helping me?"

As the conversation went on, I learned that well-meaning Christians had been telling Trevor that he needed to abandon the struggle, to "let go and let God." Moreover, victory over sin was part of the criteria these Christians were using to determine whether Trevor had fully "let go." The fact that he kept sinning, they said, was proof that he was struggling in his own strength. They also told him that a difficult Christian life is a failed Christian life, because a life defined by the indwelling of the Holy Spirit is characterized by rest, not by difficult struggle.

I paused, taking in what Trevor was telling me. Then I said the last thing he expected to hear: "Everything you've just said suggests that the Holy Spirit has been working in you."

"How's that?" he asked, visibly puzzled.

"Well," I explained, "you just shared that for years you've been struggling against the same sins and addictions. This struggle has continued despite frustration, confusion, and increasing difficulty. Have you ever considered that this could be evidence of the Holy Spirit's work in your life? After all, when the Holy Spirit moves in our hearts, the result is that we struggle against the passions that separate us from Christ, exactly as you've been doing. If the Lord were not at work in you, one would expect you to have given up by now. The fact that you've kept struggling in the face of so much difficulty may be evidence of the Lord's work in your life."

After a minute I continued. "Of course, I can't see into your heart and judge your spiritual condition—only God can do that. But I do know that Jesus promised that those who followed him would face constant struggle. The fact that the spiritual life is hard for you is not a reason to give up. On the contrary, the fact that you've persevered this much already—six years struggling against passions despite repeated setbacks—is a reason to be encouraged and to keep pressing on to the high calling."

I then shared with Trevor certain passages of Scripture showing that even the apostles struggled daily against passions and bad habits. One of these is 1 Corinthians 9:27, where Paul declares, "But I discipline my body and bring it into subjection, lest, when I have preached to others, I myself should become disqualified." In the Greek text, Paul is literally saying that he pommels (upopiazo) his body to subdue it. According to the Greek lexicon, "pommel" means "to strike one upon the parts beneath the eye; to beat black and blue, hence to discipline by hardship, coerce." The word Paul uses for "body" is soma, referring to the body itself, rather than the word for the "flesh," or "old man," which is sarx. This shows us that Paul found the spiritual life such a struggle that he had to pommel his rebellious body into submission. Paul spoke about this struggle again in Romans 7:15, where he says, "For what I will to do, that I do not practice; but what I hate, that I do."

I explained to Trevor that although Jesus lightens our load and promises us rest in the life to come, he still calls the life of faith a burden (Matt. 11:28–30), and he corrects those who suppose that following him leads only to peace (Matt. 10:34). Even in the famous passage in John 10 where Jesus promises abundant life to his followers and explains what that life looks like, he makes clear that it involves sacrificing himself for his sheep (10:7–18). And when he prepares to do this, he finds it an agonizing struggle (Luke 22:41–44).

If Christ himself struggled to be obedient to his Father's will (Matt. 26:36–44), why should we as his followers expect anything less? On the contrary, if we want to be Christ's disciples and experience abundant life, there is only one way: we must embrace the struggle, take up our cross, and follow him.

As Trevor listened, it was like a burden was being lifted from his shoulders. By the time he left my office, the terms "struggle" and "difficulty" and "trying hard" were no longer dirty words. Rather, he was able to reframe the challenges in his life as opportunities to grow spiritually. He had a new enthusiasm for carrying on as a Christian, whatever the cost and however difficult.

Struggling Against Struggle

The above account is a composite of conversations I've had and heard about over the years. Their underlying theme is the erroneous notion that when the Holy Spirit moves in a person's heart, he always enables the individual to achieve complete victory over sin—where "victory" is taken to mean the end of protracted struggle, especially struggle involving frustration, confusion, and occasional setbacks. According to this line of thinking, the presence of difficulty is a sign that God's life-giving power is not operative in a person.

In its most extreme form, this teaching asserts that once a person has fully surrendered to Christ, he reaches a state of perfection; he no longer has to struggle against sin because his sanctification is complete. Milder versions include the notion that difficult struggle is a red flag alerting us that something is wrong in our Christian life—perhaps we are walking in the flesh rather than the Spirit, or maybe we have a wrong idea about sanctification, or perhaps we are denying our salvation through trying to reform the old man.

Of course, I'm painting with a broad brush here. It's hard to generalize about the struggle-is-bad crowd since it includes believers at all points on the spectrum. Some are antinomian Christians who, wanting to steer clear of the specter of legalism, end up embracing a form of Christianity that makes few demands on their lifestyle. There is no place in their lives for struggle because the Christian life is made out to be something like a birthday party. Others are perfectionist Christians who believe they should reach a point where their sanctification is so thorough, and the work of the Holy Spirit in their hearts so pervasive, that they no longer have to struggle with the old man. For both types, spiritual struggle is out of place, a sign that something is amiss.

I recently received an email from a longtime friend who seemed to hold some of these views. He was responding to an article I had published with the Colson Center, in which I made the following claim (which, at the time, I did not think particularly controversial):

[W]ithin the context of a Spirit-filled life, struggle can play a positive role, as we literally exercise ourselves toward godliness (1 Tim. 4:7) and follow Christ's example of running the race with endurance.

When . . . we fail, we may be tempted to give in to a sense of discouragement and defeat. . . . However, by keeping our eyes fixed on Jesus our goal, and the joy that is set before us at the end when we are fully united with Him, we can find the energy we need to get right back up and keep struggling. Before our spiritual muscles are fully developed (and even afterwards), we may stumble and fall more times than we can count, but what do we do? We get up and keep struggling, fixing our gaze on Christ.

My friend was skeptical. "Are you indeed able to struggle yourself into a more sanctified life?" he asked. Significantly, the criterion he was using for whether struggle worked was the absence of "continued failure as you struggle." He seemed to assume that failure would be a reason to stop struggling and find a different approach to spiritual growth. He cited his own experience, claiming that his sanctification was "utterly complete" and that there was "nothing left to be accomplished" with regard to either his salvation or his sanctification. But is "continued failure as you struggle" a legitimate reason to stop trying? Is it really an indication that a different approach is required? Not according to St. Paisios (1924–1994). Here's what he had to say about struggle and failure:

The person that is struggling to the best of his abilities, who has no desire to live a disorderly life, but who—in the course of the struggle for faith and life—falls and rises again and again, God will never abandon. And if he has the slightest will not to grieve God, he will go to Paradise with his shoes on. The Benevolent God will, surprisingly, push him into Paradise. God will insure that he takes him at his best, in repentance. He may have to struggle all his life, but God will not abandon him; He will take him at the best possible time.

Normal Is Not Comfortable

The struggle-less approach to Christianity is at odds with the most ancient expressions of the faith, which saw comfort as a danger and put a high premium on spiritual struggle. In the earliest days of the Church, no one needed to be reminded that being a Christian was difficult, since Christians were hounded and killed. But after Constantine ended persecution in a.d. 313, and especially after Theodosius made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire in 380, it became to be easy to be a Christian. As much a blessing as this was, many viewed the new ease as spiritually unhelpful. After all, hadn't Jesus said that the way to the kingdom of heaven was through poverty of spirit (Matt. 5:3), mourning (5:4), and persecution (5:11–12)?

As a way of compensating for the newfound ease, Christians began exploring various forms of self-imposed sufferings, such as fasting, voluntary poverty, living in isolation, staying up all night to pray, and other ascetic disciplines. As St. John Chrysostom (347–407) said in one of his sermons, "Mortify your body; crucify it, and you will receive the martyr's crown. What the sword did for the martyrs, let your own will do for you." Early Christians did not do these things because they believed God wants us to be miserable but because they believed that "we must through much tribulation enter into the kingdom of God" (Acts 14:22).

Although many centuries have elapsed since then, our faith hasn't changed. Christians are still called to embrace a life of spiritual struggle. I will go so far as to say that if our spiritual life is comfortable, if we find it restful rather than difficult, then we should seriously question whether we are fully following Christ. There will be a time to rest, but it isn't yet. Rest awaits us on the other side of the grave, when we are with the Lord in paradise; right now we are called to struggle.

Those of us so blessed as not to be faced with persecution, or with weighty and significant problems on a day-to-day basis, would do well to heed John Chrysostom and seek out ways to introduce a little struggle and discomfort into our spiritual lives.

This might mean giving money to the poor—and giving more than is comfortable. One might, for instance, consider foregoing something he really wants but does not actually need (a new car perhaps, or a vacation, or a dinner out) and using the money to help a struggling family in his church. Or, where such is feasible, one might consider moving into a smaller house and using the money saved to help a poorer family give their children a Christian education.

Another good way to embrace a little discomfort is to volunteer one's time. Some of the hours normally spent watching sports or other TV, or in recreation, could be used instead to help another family in one's church—perhaps a family with lots of children, that could use help with childcare, housework, homeschooling, or running errands. One might even consider doing this regularly, as part of the weekly routine.

Other ways to embrace spiritual struggle include making an effort to discipline your mind and develop a habit of constant interior prayer, or working to overcome seemingly innocuous habits like complaining, wasting food, or spending too much time online. If you know of a fellow Christian who is suffering, you might commit yourself to getting up in the middle of the night to pray for him or her. Or, if getting up in the wee hours is too much, you could sacrifice movie-watching or pleasure-shopping time to pray for that person—and do it not just once or twice, but regularly.

For the average American Christian, the response to all these suggestions is likely to be yes in theory but no in practice. Generally, we are not willing to impose this level of discomfort on ourselves even for those we love. When we give our time or money, we give out of our abundance and stop short of giving where it hurts. Nevertheless, we like to think that if we were called to face martyrdom for the gospel we would faithfully do so. But if we are not willing to embrace struggle and discomfort to ease the burdens of those Christ has placed in our midst, how can we suppose we would have the spiritual fortitude to endure martyrdom? How can we say we love Christ if we are not willing to sacrifice for the sake of those he has given us to serve (1 John 4:20; Matt. 25:42–45)?

Educated for Comfort

Still, for most Americans, the idea of voluntarily seeking out tribulation seems crazy. Even if we Christians acknowledge that following Jesus comes with a cost, we rarely choose to go out of our way to suffer for the gospel. Our resistance to struggle may partly be attributable to the culture of comfort that stamped itself on our unconscious during our earliest educational formation.

In the 1990s James Stigler, a psychology professor at UCLA, teamed up with James Hiebert from the University of Delaware to study pedagogical trends in elementary schools. They analyzed hundreds of hours' worth of video footage from eighth-grade mathematics classrooms throughout the United States and published their findings in The Teaching Gap: Best Ideas from the World's Teachers for Improving Education in the Classroom (The Free Press, 1999).

One prominent trend that emerged from their study was American teachers' tendency to minimize struggle in their students whenever possible. Teachers strove to make math as easy as they could and to eradicate confusion and frustration. One way they did this was by offering tricks to help children get the right answers even when they didn't understand the underlying concept.

The assumption that struggle is bad is not limited to eighth-grade math teachers. Most of us have been conditioned to think that learning comes easily to smart kids—that they can fly through their homework and achieve straight A's with very little effort. That's how we distinguish them from the poor or merely average students, who find schoolwork confusing and frustrating and have to struggle to get good grades. It is just this confusion and frustration, Stigler and Hiebert observed, that American teachers think "should be minimized":

Teachers act as if confusion and frustration are signs that they have not done their job. When they notice confusion, they quickly assist students by providing whatever information it takes to get the students back on track. Teachers in the United States try hard to reduce confusion by presenting full information about how to solve problems.

The researchers also analyzed footage from classrooms in Japan and noticed a stark contrast: Japanese teachers believe that struggle is an integral part of the learning process. They will intentionally set their students math problems that are too hard for them and that the teachers know will result in mistakes. But they do this anyway to force the students to struggle. According to the mindset in Japan (and much of East Asia), the successful student is not the one who gets his work done with ease, but the one who persists in his work despite frustration and failure.

Thus, the same behaviors that Americans regard as failing, the Japanese think of as learning. To many Asians, the students who show they can persevere through repeated setbacks are the ones who are preparing themselves for great things later in life.

Wider research in cross-cultural psychology shows that these contrasting orientations towards educational struggle are rooted in the different ways Asians and Westerners perceive the development of character, intelligence, and skill. Most East Asians believe that these qualities result from what one researcher called "dull and determined effort" over long periods of time. But a majority of Westerners (particularly in the English-speaking nations) tend to view character, intelligence, and skill as resulting from innate ability or sudden flashes of insight. Accordingly, Americans are prone to take the lack of prompt success in some endeavor as a sign that the person just doesn't have what it takes, instead of as a reason to engage in further struggle.

Our classrooms are just one area where these assumptions about struggle have been incarnated. A cursory glance at our approach to music, art, farming, economics, even meal preparation, reveals a bias towards quick-fix solutions over slow and steady achievement through hard effort. Even our sense of self is often tinctured with the assumption that our identity and personality traits are authentic to the degree that they come naturally to us, where "natural" refers to raw experience untouched by struggle, effort, and difficult habituation.

For example, under the rubric of "being true to yourself," people are discouraged from working to develop attitudes and behaviors that don't come easily, as if virtues attained after protracted struggle are somehow contrived and artificial. It is often supposed that one's highest calling is to be like Elsa in the Disney film Frozen, who had to learn to stop trying to be the good girl everyone expected her to be, and instead to simply "let it go" and be herself—that's how she would realize the authentic person she was inside.

Being "authentic" is thus correlated to following the path of least resistance. The implication is that spending years to develop habits and dispositions that do not come naturally is repressive, hypocritical, less "true to yourself," and less genuine than "letting go" and following the impulses that come naturally, without effort.

Towards a Theology of Struggle

The Church has been infiltrated by these worldly assumptions. Indeed, many Christian pastors routinely teach that there can be a shortcut to sanctification that bypasses effort and struggle. Andy Naselli gives a helpful survey of this teaching in his book Let Go and Let God? (Lexham Press, 2010), where he traces the history and dissemination of the idea of "monergistic sanctification," the notion that holiness comes from God doing everything and the believer doing nothing.

One of the teachers Naselli cites is Evan Henry Hopkins (1837–1918), who reflected a widespread belief when he answered the question, "What then is needed on the part of the believer in order that his life may be a life of triumph?" by averring, "Not struggles with the flesh to overcome it. . . . It is not by straining and struggling that this blessed condition is brought about." Similarly, Charles G. Trumbull, editor of the Sunday School Times and a co-founder of America's Keswick convention, asserts in his book Victory in Christ (CLC Publications, 1980):

If any of you are making the mistake of trying to live the victorious life, you are cheating yourself out of it, for the victory you get by trying for it is a counterfeit victory. . . . Trying is what we do, and trusting is what we let the Lord do. . . . The counterfeit victory means a struggle.

The notion that trying to follow God is useless does have an intuitive grammar about it. After all, how many of us have struggled with an issue in our lives to no avail, and then, all of a sudden, God helps us in a way we never could have managed on our own? Deep down, most of us know how inadequate and helpless we are; hence, it often feels right to say that God does everything and man does nothing. Moreover, many of us worrythat if our own struggling efforts were instrumental to spiritual growth, we would have a basis for pride. Given these instincts, it is natural to view the spiritual life as a zero-sum game: God can only get full glory when human agency is eradicated or denied. This zero-sum approach creates a web of rigid dichotomies in which trying becomes antithetical to trusting, struggle becomes antithetical to grace, and faith becomes antithetical to works.

Certainly it would be a mistake to think that we can do anything profitable—much less overcome sin—without the enabling power of the Holy Spirit. But it is equally mistaken to deny that God works through creaturely means. In his providence, he has seen fit to structure the world so that certain things—the sacraments, prayer, other people, and yes, our own feeble efforts and struggles against temptations—are means by which he accomplishes his plan for us and works holiness in our lives. There is no room for pride, since even our ability to struggle against temptation comes from the Holy Spirit's working in our hearts.

Paradoxically, it is those who deny that struggle plays any role in the Christian life who end up robbing glory from God, since they deny that God is powerful enough to work in and through our struggles. When we come face-to-face with the full extent of our fallen condition and have constant reminders of our spiritual inadequacy and helplessness, it's easy to believe that the only solution is for God to do everything while we do nothing—for the Holy Spirit to wipe out our problems with a silver bullet that zings past the cycle of struggle, failure, frustration, more struggle, and so on, that characterizes our lives. It takes a lot of childlike faith to believe the Holy Spirit is powerful enough to use our puny struggles to bring us closer to him.

Falling Forward

When we see struggle as alien to the spiritual life, we often don't know what to do with suffering, and we have trouble coming to terms theologically with human weakness, failure, disappointment, confusion, and frustration. Instinctively we tend to assume that experiencing suffering means that God is displeased with us.

This is not a universal mindset, however. Russian Christians frequently emphasize the concept of spiritual struggle, as encapsulated in their word podvig. There is no English equivalent for podvig, but the term conveys the idea of a good hardship or spiritual struggle, a God-ordained difficulty.

Podvig is part of a larger understanding in Russian Christianity that painful struggle can be a good thing. In the ancient Russian translation of the Bible, the word appears in Colossians 2:1, where Paul describes his agonizing struggles on behalf of the Christians in Colossae and Laodicea. It also appears in Hebrews 10:32, where the author calls to mind the days when believers endured a great conflict of suffering for the gospel.

When I first learned about podvig, it ran contrary to my American sensibilities, for I had been told countless times that a Spirit-led life should not be a struggle, but should come easily. One teacher told me it should be as easy as a boy rolling down a hill, while others said that frustration, confusion, and struggle were signs of living in the flesh rather than the Spirit. The concept of podvig challenges us to go back to the Bible and reassess matters. When we do, we find that the Christian life is actually very difficult, and that we are in a constant state of war against our fleshly lusts (1 Peter 2:11).

Indeed, Scripture shows that love is a battlefield. To love is to be at war, for love can only be preserved through struggle and painful commitment, by taking one difficult baby step after another. As we struggle forward towards him who is Love, we grow holy not by never falling down, but by getting back up and resuming the struggle.

In The Secret Thoughts of an Unlikely Convert, Rosaria Butterfield, a former lesbian, chronicles her struggle to put Christ's teaching into practice in her own life. She has found that the journey to Christ involves constant struggle and failure, but most importantly, it requires perseverance:

Winners have always seemed to me people who know how to fall on their face, pick themselves up, and recover well. It has always seemed to me that without the proper response to failure, we don't grow, we only age. So I was and am willing to take the risk of being wrong for the hope of growing in truth. It seems to me that if we fall, we need to fall forward and not backward, because at least then we are moving in the right direction.

Of course, this does not mean struggling in our own strength or trying to earn favor with God through works-righteousness. Even the ability to struggle towards holiness comes entirely from God's grace, for apart from Christ we can do nothing (John 15:5).

Yet, because Christ's love forms the context for our struggle, there can be a lightness in the midst of suffering, a joy in the midst of toil, and a peace in the midst of pain. Think of the saints who were tortured for their faith—in them we see peace, joy, and hope running parallel with incredible torment and pain. Christ's burden is truly light (Matt. 11:28–30), not because he takes away our struggles, but because he gives us supernatural grace and peace in the midst of them.

If we look into the faces of people whose lives revolve around the pursuit of sinful lusts, we often see how severe is the toll exacted by their lifestyle. In many respects, sin is hard work, but its fruits are things like heaviness, anxiety, hopelessness, and despair. Those who strive to live for others and who strain after virtues like humility, gratitude, compassion, and charity also find life hard work, but the fruits they reap are things like serenity, inner well-being, and joy. It is in this sense that we should understand Christ's promise to lighten our burdens and give us perfect peace.

Robin Phillips has a Master’s in Historical Theology from King’s College London and a Master’s in Library Science through the University of Oklahoma. He is the blog and media managing editor for the Fellowship of St. James and a regular contributor to Touchstone and Salvo. He has worked as a ghost-writer, in addition to writing for a variety of publications, including the Colson Center, World Magazine, and The Symbolic World. Phillips is the author of Gratitude in Life's Trenches (Ancient Faith, 2020), and Rediscovering the Goodness of Creation (Ancient Faith, 2023). He operates a blog at www.robinmarkphillips.com.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

8.4—Fall 1995

The Demise of Biblical Preaching

Distortions of the Gospel and its Recovery by Donald G. Bloesch

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor