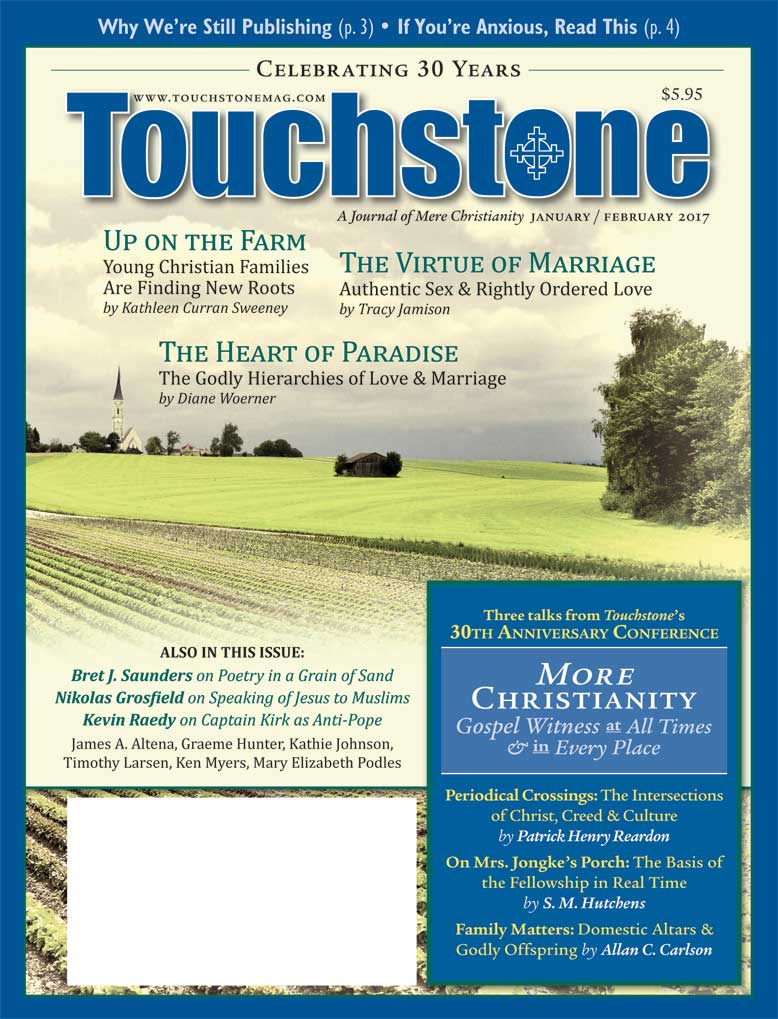

Conference Talk

Family Matters

Domestic Altars & Godly Offspring

Social conservatives and small-o orthodox Christians of sufficient age still tend to look back longingly to the middle decades of the twentieth century as a golden era. From the mid-1940s to the mid-1960s, church construction proceeded at a frenetic pace, with the number of Christian edifices climbing by 80 percent, mostly in the burgeoning suburbs. Young families filled the pews. Sunday schools and parish schools were bursting at the seams. The seminaries were filled with future pastors and priests. In short, Domestic Altars and Godly Offspring seemed to give a fresh iteration to the Righteous

Republic.

Was it real? Early on, as David Dockery noted in his fine talk, sociologist Peter Berger famously said no. His research into the motivation of suburbanites for joining churches showed that they rarely claimed a life crisis, a conversion experience, or deep religious sentiments. Rather, in Berger's words, "for most of these people the decision to join was prompted by the prospect or presence of children in the family." In this view, church membership was simply another step in building the "okay world" of the American middle class, akin to Little League and the PTA.

In her 2013 book, How the West Really Lost God: A New Theory of Secularization, Mary Eberstadt makes the same basic point. She argues that the "religious boom" of the 1940s and 1950s was, in effect, the product of the "marriage" and "baby" booms of that era. The emergence of more and larger families drove up the number of churches and worshipers, not the other way around. Her implication is that religious belief and action are in key ways dependent, secondary forces, unable to make an intentional or real difference.

On this question, though, I must dissent. "Real" things were going on, although they varied by denomination.

Catholic Flowering

Roman Catholics of the 1940–1965 era, for example, were the beneficiaries of a century-long confluence of doctrinal and material construction. Regarding the former, devotion to the Virgin Mary and emphasis on her maternal character received growing papal encouragement, beginning with the proclamation of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception in 1854. Reported appearances of the Virgin in Lourdes and of Mary, Joseph, and John the Evangelist in County Mayo, Ireland, fed this turn. Encyclicals from Pope Leo XIII urged families to say the rosary together, enhanced attention to Joseph, granted special indulgences to those who prayed before the image of the Holy Family, and cast "the natural and primeval right of marriage" and the "society of the household" as the proper foundation for social and economic justice in the new industrial age. Absorbing sentiments from Protestant neighbors, the American Catholic mother became a "home hero" and a "priestess of the domestic shrine."

Occurring in parallel after 1845 was the vast construction of churches, Catholic schools, seminaries, convents, and monasteries: a mighty institutional edifice launched by poor immigrants that reached its pinnacle during the 1940s and 1950s.

I would argue that doctrinal integrity blended with these physical and organizational church structures to produce a "heroic" flowering of Catholic family life in America. While all American Christians experienced an increase in fertility during these years, the baby boom came earlier and was far more pronounced among Catholics. It was especially strong among women who had studied at a Catholic college, and was tightly bound to weekly attendance at Mass. Put another way, doctrinal clarity and institutional strength preceded—or produced—stronger and more prolific families.

Protestant Flowering

Among Evangelicals, too, something more than "suburban socialization" was occurring. If the fundamentalists of the 1920s seemed to have retreated from the public square after the Scopes Trial, it was in part to lick their wounds; but then, to repair and modernize their ministries and begin to re-enter the culture and reach out to the unchurched. A profusion of new Bible institutes, colleges, prophecy conferences, magazines, book publishers, foreign mission groups, and summer Bible camps was supplemented by the new medium of radio, which Evangelical entrepreneurs mobilized brilliantly. By the time Billy Graham burst onto the national scene through his 1949 Los Angeles Crusade, the New Evangelicalism was already in high gear. The harvests of conversions during the 1945–1965 era were, proportionally speaking, at least as impressive as those of the more celebrated Great Awakenings of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. While the effects of the twentieth-century awakening on Evangelical family life has been less well documented than similar developments among Catholics, research has shown a "significant and positive relationship between Evangelicalism and fertility" over the whole of the second half of the twentieth century.

Even the Protestant "mainline" showed evidence of real change in a pro-family direction. It is true that during the 1930s and 1940s the acceptance of birth control for married couples came to characterize most of the mainline denominations. Yet this occurred, at least in part, because the American birth-control movement itself had swung in a relatively conservative direction. By 1942, the radical Margaret Sanger had been pushed out, replaced by male leadership, and the Birth Control Council of America was renamed Planned Parenthood. The new leaders insisted that their work "did not mean smaller families but, rather, planned families—and therefore healthier children." Child spacing, not birth prevention, became the mantra. The voice of the mainline, the Federal Council of Churches, caught the new spirit, arguing in a 1946 policy statement that "for the individual family, there is nothing more satisfying, even though it may involve real sacrifice, than to have at least three or four children."

Fresh doctrinal attention to the Christian family appeared in other ways. Emerging from the relatively liberal United Lutheran Synod, William H. Lazareth devoted his 1958 doctoral dissertation to Luther on the Christian Home. Written in part to refute Roman Catholic contentions that Luther left Rome in order to marry, and in equal part to refute Protestant voices saying that Luther had no consistent theology of marriage and family, Lazareth "confidently" concluded "that Luther married as a public testimony of faith in witness to his restoration of the biblical view of marriage and home life under God." Indeed, Lazareth showed how Luther "dramatically reaffirmed the sacredness of all of God's creation by stressing the ordinary tasks of the common life"; and these were nowhere more apparent and important "than in the God-ordained fortress of our common life, the Christian household."

In short, in refutation of the shared argument of Berger and Eberstadt, the family renewal of the middle decades of the twentieth century is better seen as the consequence, rather than the cause, of religious renewal, a social force resting on doctrinal and institutional integrity.

Church Failures

So what went wrong? Why did all of the indications of family strength—early marriage, nearly universal marriage among adults, a relatively high average family size, a falling divorce rate—why did they all shudder and collapse between 1965 and 1977?

The short answer? It was the failure of the churches. That failure took form in three ways.

The first of these was a broad complacency among religious elites. A healthy family system, and the social benefits that it delivered, was taken for granted. The deliberate, and usually difficult, efforts of persons in earlier generations to build a family-centered order went unappreciated or forgotten. Rather, religious leaders were prone to experiment with aspects of the religiously grounded family order they inherited, oblivious to potential damage and unforeseen consequences.

For example, the return in the mid-1960s of equity feminism, this time with an angry twist, pushed mainline Protestant leaders into a quick embrace of the ordination of women. This break with four hundred—or nineteen hundred—years of practice (depending on how you count) occurred with astonishing speed. Little attention was given to "macro" issues, such as the effect on ecumenical relations with Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox communions, nor to "micro" matters such as the impact of female ordination on the informal, albeit important calling of "pastor's wife." The spirit of the age demanded this radical and secular form of equality. Mainline theologians and leaders delivered.

The Embrace of Dissent

The second failure of the churches that lay behind family collapse was the open embrace of strident dissent, the encouragement of attacks on the common, orthodox Christian understanding of marriage, sexuality, and family. The precursor event here, mentioned earlier, was acceptance of the use of birth control by the Protestant mainline. Accommodation to modernity and the supposed actual practice among the laity were the common arguments used to justify this move. Most advocates for change downplayed its significance. However, the defeated defenders of Christian orthodoxy feared for great and terrible consequences: not a few traditionalist Anglican bishops were seen weeping outside the Lambeth Hall in 1930.

The 1960s brought in voices much darker and more disturbing. In 1961, the National Council of Churches held a conference on "Foundations for Christian Family Policy." Moving well beyond birth control, speakers openly dismissed the historic Christian experience, attacked biblical family norms, and embraced modern sexology and therapeutic psychology in their place. Setting the tone was keynote speaker J. C. Wynn of Colgate Divinity School, who denounced existing Protestant statements and books on the family as "depressingly platitudinous," "comfortably dull," and a regrettable "works righteousness."

Disturbingly, the list of speakers was a veritable who's who of anti-religious intellectual celebrities. Sociologist Lester Kirkendall declared that America had now "entered a sexual economy of abundance," allowing for unrestrained experimentation in sexual delights. Wardell Pomeroy, director of field research for the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research, called for the abandonment of moral judgements of any kind. "The concept of normality and abnormality is worse than useless," he stated. "It gets in the way of our thinking." Psychologist Evelyn Hooker (her real name) praised the healthy, well-adjusted lives of most homosexuals. Mary Calderone, president of a re-radicalizing Planned Parenthood, urged churches to help individuals shape their own private values about sex, while Alan Guttmacher blamed America's existing, "mean-spirited" anti-abortion policy on the antiquated pro-natalism of the Jews (that's a sophisticated, radical form of anti-Semitism).

The conference's final report marked a total collapse of the Christian family ethic among mainline Protestant leadership. It appealed to "the freedom we have been given in Christ" to justify clear antinomian ends. The "outdated moralisms" and "respectable traditions" of the Christian past should be jettisoned, it concluded, while Christian marriage should be unmasked as "idolatry."

Even recent defenders of a healthy Protestant family ethic fell into line. For example, William Lazareth—author of that excellent book, Luther on the Christian Home—had a leadership role on the committee that drafted a 1970 statement on "Sex, Marriage, and Family" for the recently created Lutheran Church in America. Its primary theme was that "the family should not become centered on itself." Instead, the text declared a "right" for adults not to have children, and gave blessings to the practices of contraception and abortion (this coming three years before the Roe v. Wade decision).

Councils & Their Aftermath

When Pope John XXIII convened the Vatican II conclave in October 1962, he appears to have anticipated a kind of ecclesiastical house cleaning, a brushing away of some theological and liturgical cobwebs that had accumulated over the past few centuries. Indeed, the timing seemed right: the Roman Catholic Church appeared to be strong and self-confident, certainly strong enough to survive some modest reforms without rancor or blemish. What the pope failed to perceive, I think, were the radical elements latent within his church, and their external allies, who were waiting for the gates of orthodoxy to be lowered and open debate encouraged.

Sexual issues soon came to the fore. The Catholic physician John Rock was one of the creators of the first oral contraceptive; he called on the church to embrace "the pill" as an acceptable Catholic means of birth control. In these years, the bogus "global population crisis" also grew in intensity. In 1963, Pope John created a commission to study these questions. Its final report, delivered to his successor, Paul VI, in 1966, urged the papacy to approve the use of some forms of contraception by married couples. Numerous Catholic theologians and bishops from Europe and North America added their encouragements. Only Paul VI's unexpected, stunning affirmation of Catholic orthodoxy on these matters in Humanae Vitae (1968) kept Roman Catholicism from following down the Anglican and mainline path.

American Evangelicals held their own parallel consultation in August 1968. Entitled The Control of Human Reproduction, the event was co-sponsored by the journal Christianity Today and the Christian Medical Society. Attendees formed a veritable who's who" of the New Evangelicalism: Walter O. Spitzer (Christian Medical Society), Carl F. H. Henry and Harold Lindsell (CT), Harold J. Ockenga (pastor of the venerable Park Street Congregational Church of Boston), Bruce Waltke (Dallas Theological Seminary), Paul Jewett (Fuller Seminary), John Warwick Montgomery, and so on.

The dark surprise here was the degree to which Evangelicals also embraced the emerging "new" sexual ethic. Again, the year was 1968: a strange and ungenerous spirit hovered over the conclave. For example, Waltke argued that "God does not regard the fetus as a soul, no matter how far gestation has progressed." Jewett agreed that the humanity of the fetus "cannot be demonstrated." Robert Meye of the Northern Baptist Theological Seminary declared that "Neither the Old Testament nor the New speaks of procreation as the end of the sexual union." The sexual act alone—not the bearing of children—had redemptive significance. And so on, through a now familiar list. Relative to theology, sexual radicals could have asked for little more.

The Consultation's consensus statement, "A Protestant Affirmation on the Control of Human Reproduction," is sobering. Statements of agreement by all attendees included:

• "The Bible does not expressly prohibit either contraception or abortion."

• The use of birth control is acceptable "provided the reasons for it are in harmony with the total revelation of God for the individual life."

• Methods of contraception are not a religious matter but rather "a scientific and medical question to be determined in consultation with the physician."

• ". . . about the necessity and permissibility for [abortion] under certain circumstances we are in accord."

• "The legal code" should not interfere with such choices; changes in state laws to allow "therapeutic abortion" should be encouraged.

• "Much human suffering can be alleviated by preventing the birth of children where there is a predictable high risk of genetic disease or abnormality."

• "This Symposium acknowledges the need for Christian involvement in programs of population control at home and abroad."

In these ways, Evangelical leaders also moved over to the dark side (at least for a time).

The Resurgence of Gnosticism

The third failure of the churches came as they let down their guard, allowing for a return of the gnostics. Our conference began with Robby George's talk on this matter. It seems significant that we end on the same question.

As Dr. George indicated, the core of gnosticism is the separation of mind from body: the celebration of spirit and thought and the denigration of creation, materialities of any kind, and nature. In a provocative recent paper, "The Ordination of Women and Ecclesial Endorsement of Homosexuality," Lutheran theologian John T. Pless asks: "Are They Related?" He suggests ten ways in which they are. Some are of practical or political relevance: for example, both practices are pushed as matters of social justice; the opponents of both practices are derided as "fundamentalists and legalists"; and both "are urged on the church for the sake of unity and inclusiveness."

More telling, though, are the gnostic arguments mobilized in their favor. Notably, advocates for the ordination of both women and homosexuals reinterpret Galatians 3:28 ("There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is neither male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus") to sever redemption from creation. Human sexuality—the male and female thing—was part of creation, they say, part of the old order. In Galatians, Paul renders obsolete these sexual distinctions, sending humans instead on a spiritual journey, one broken free from the restraints of nature. Patriarchal structures such as a male-only clergy and heterosexist claims of divine favor from Genesis 1 and 2 thus become irrelevant. Other biblical texts that affirm male headship and a divine blessing on heterosexual marriage are dismissed as either time-specific (that is, applicable only to the ancient Hebrews or the first generation of Christians) or else trumped by a "freedom of the gospel" dedicated to empowerment and change.

These are pure examples of gnosticism at work, where—in Pless's words—"creation is left behind in pursuit of purely spiritual categories and relational qualities." On sexual matters, gnosticism can move in two otherwise incompatible directions: either toward an absolute denial of sex, or toward complete licentiousness, sexual abandon. Neither end has any place for procreative marriage or the generation and tender care of children.

Moreover, once unleashed, the "logic" of gnosticism is difficult to contain. William Lazareth provides an example again. As director of the LCA's Department for Church and Society and later as a bishop of the Metropolitan New York Synod of the again newly merged Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, he helped preside over the integration of ordained women into his denomination, accepting the arguments advanced in the practice's favor. However, in the mid-1990s, he sought to prevent the march toward homosexual marriage. As he wrote: "Clearly, same-sex 'unions' do not qualify as marriages to be blessed for Christians who have been baptized as saints into the body of Christ. The Lutheran church should not condone the sinful acts . . . of an intrinsic disorder . . . in God's heterosexual ordering of creation." A nice phrase, "God's heterosexual ordering of Creation." Alas, his ELCA would do just that in 2009, the year after his death. Once you start down the gnostic path, it becomes impossible to draw lines.

A Time to Heed Malachi

So what should be done? How might mere Christians restore domestic altars in their homes and give to God that which he desires, "godly offspring" (Mal. 2:15)?

The good news here is that religious behavior grounded in fidelity to doctrine is an independent actor in human affairs. Contrary to the sociologists cited earlier, Christian believers can free themselves from the broad social and cultural currents and build anew a family-centered social order. My recent book, Family Cycles, examines such successful episodes in the American past:

• In the seventeenth century, the Puritans of New England saw the faith-grounded family unit as the vehicle through which to regenerate society and build their Christian commonwealth: "the nucleus of moral armament and stability."

• In the eighteenth century, the exemplary Quakers rested their whole religious project on a family system grounded in marriage and focused on intensive childrearing, designed to make home life "fascinating, profound, and sacred."

• In the nineteenth century, American "Victorian" Christians such as Horace Bushnell, Sarah Hale, and Lydia Sigourney crafted "a finely wrought ideology" of the Christian home, resting on what they called "the Eden Laws" of marriage and procreation.

• And in the twentieth century, as discussed earlier, the Roman Catholic hierarchy, the New Evangelicals, and a partially re-energized "mainline" contributed—each in different ways—to the marriage-baby-family boom of the mid-twentieth century.

In each case, measures of family health improved through these efforts: sometimes dramatically so.

It is equally true that each of these episodes ran out of steam after two or three generations, as complacency and the usual temptations, quietly nourished in the lairs of Old Scratch, returned. In this sense, we Americans are no different from the Hebrew people of the Old Testament. Their story is one of decline into disbelief and hedonism, followed by a summoning back to the faith and moral order by a new band of prophets.

The last of these, Malachi, blasted the people of Israel for turning toward divorce and avoiding the birth of children. In the closing verse of the Old Testament, he warned (in a translation from Zondervan's The Amplified Bible): "And Elijah shall turn the hearts of estranged fathers to the ungodly children and the hearts of rebellious children to the piety of their fathers . . . lest I come and smite the land with a curse (Mal. 4:6).

On the one hand, we live in a time of moral collapse: public sexual depravities such as "pride parades" that would awe the Sodomites, a marriage system in shambles, a tumbling fertility rate, girls and young women pressured simultaneously to be sexually promiscuous and sterile, and a lost generation of video-gaming young men and their digital girlfriends.

On the other hand, we may also be on the cusp of a time of moral, social, and familial renewal, driven by new expressions of religious belief and fervor. What forms these expressions would take—or might already be taking—will surely be different in certain particulars, but familiar in the basics: a rebuilding of domestic altars and a welcoming of Godly offspring. •

Allan C. Carlson is the John Howard Distinguished Senior Fellow at the International Organization for the Family. His most recent book is Family Cycles: Strength, Decline & Renewal in American Domestic Life, 1630-2000 (Transaction, 2016). He and his wife have four grown children and nine grandchildren. A "cradle Lutheran," he worships in a congregation of the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod. He is a senior editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

more from the online archives

33.2—March/April 2020

Christian Pro-Family Governments?

Old & New Lessons from Europe by Allan C. Carlson

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor