Conference Talk

Periodical Crossings

The Intersections of Christ, Creed & Culture

All of us know that Touchstone is a journal of commentary. Its dominant and almost exclusive literary form is the essay. We publish neither poetry nor fiction. Our subject matter is limited to the interests of our writers and, on occasion, we hope, our readers.

Touchstone, we know, began publication 30 years ago, and I became involved with it three years later. I became the first non-Protestant member of the editorial board. Indeed, I gave what I believe were the first three Touchstone lectures, in Chicago, in January of 1989. That was the occasion when I first met senior editors Tom Buchanan and Steve Hutchens.

During that period I was assiduously reading another journal of essays, called The Rambler. I confess today that, from the beginning, I have taken the content and style of the Rambler essays as my personal model for what Touchstone should try to accomplish.

Those of you familiar with the essays of The Rambler may think this an unusual journalistic standard. After all, The Rambler was published in the mid-eighteenth century. Directed to the emerging middle class, it presented essays commenting on literature, philosophy, history, and culture, all of them elevated by disciplined prose and a pronounced moral tone.

Such observations, however, oblige me to remark on the most obvious difference between The Rambler and Touchstone: whereas Touchstone is put together by several editors and many writers, The Rambler was completely produced by the mind and pen of just one man. Here, indeed, the difference between the two journals is immense. My fellow senior editors, I am certain, agree that all of us taken together are hardly to be compared with that one man. Whatever our individual merits, the Touchstone editors recognize, in repentance, that all of us have sinned and fallen short of the glory of Samuel Johnson.

Horizontal & Vertical Lines

A special feature of Touchstone I want to present today is this: our journal is a field of intersections, a place where lines of intellectual and moral inquiry are deliberately crossed at specific and critical points. Indeed, I hope to identify and examine several points that define the very character of Touchstone.

Let us first consider what I will call Touchstone's convergence of horizontal lines. There are many points in our enterprise where various horizontal lines—earthly trajectories—come together. Touchstone is not just a journal of theology. We endeavor to meet the need of what Eric Miller calls "earthy intelligence."

The interests of our journal include philosophy, history, sociology, literature, science, education, law, the arts, and other expressions of culture. Most or all of these disciplines are represented, in fact, in the publications of our senior editors.

Each of these disciplines has its own history; each has its own expected standards and its own methodology. Moreover, each subject has its own areas of controversy. All these things contribute, I believe, to a considerable richness, diversity, and flexibility in the Touchstone mix.

Since each of the Touchstone senior editors is something of a peritus in his particular field, all of us depend on one another for guidance when we are faced with the sundry manuscripts and proposals we receive from outside. If, for instance, we receive a proposed article espousing the notion that the moon is made of green cheese, we expect Dr. Tom Buchanan to mention, for the enlightenment of the rest of us, that such a thesis is not currently in vogue among reputable astrophysicists.

And then there is politics. Although Touchstone tends to avoid politics in a partisan sense, hardly any of these other subjects is unrelated to political considerations. Touchstone is an American journal. I submit, indeed, that a major preoccupation always at work in our writing is how to share the gospel light in a liberal democracy.

The myriad points formed by the convergence of horizontal lines, however, are further crossed by vertical lines. An essential trait of Touchstone is the clear assumption that it looks for—and very much depends on—direction from on high. A vertical reference slants up from our every page. If a submitted essay does not exhibit such a reference, it has no chance of our accepting it.

In this respect Touchstone differs from other contemporary essay journals—even those I regularly read and respect; I am thinking of truly fine publications, such as The New Criterion, Modern Age, and The Claremont Review of Books.

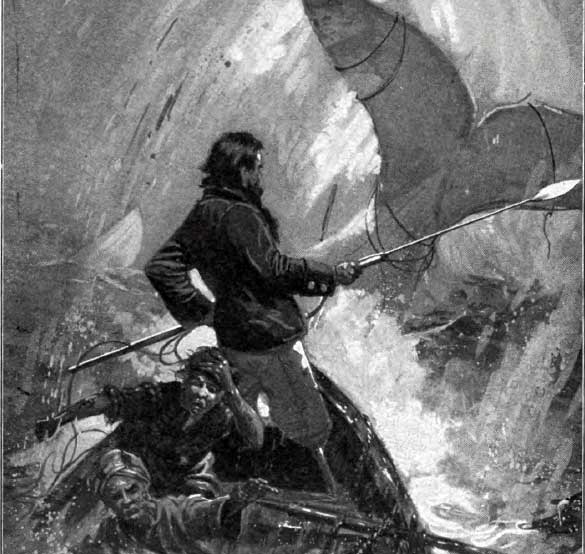

Ahab's Rebellion

Perhaps I should illustrate what I mean when I speak of the crossing of horizontal and vertical lines in Touchstone. Return with me, if you will, to chapter 118 of Moby Dick, to the scene where the whaling vessel Pequod draws near the equator. It is one of the most dramatic parts of the story . . . and arguably the key to the rest of it. Captain Ahab goes into the ship's boat and starts to use his quadrant to help establish his latitude bearing.

Abruptly, however, Ahab is seized with a mighty revulsion; he rebels against what he regards as the arbitrary necessity to ask guidance from on high. Ahab curses his quadrant.

We observe that the captain does not distrust the quadrant. It is not that he thinks the instrument defective. No, what Ahab objects to is the very idea that he must rely on guidance from above. To him, the calibrated markings on the quadrant appear as a form of hieroglyphics. Ahab resists the dominance of this ancient and authoritative code. He resents being bossed around by a vertical reference.

"It was hard upon high noon." Melville tells us, "and Ahab, seated in the bows of his high-hoisted boat, was about taking his wonted daily observation of the sun to determine his latitude."

Ahab is overwhelmed, at this point, by the immensity of the sea and the sky, which embody an irresistible and ineffable sense of the infinite, against which every man is powerless. Melville writes,

Now, in that Japanese sea, the days in summer are as freshets of effulgences. That unblinkingly vivid Japanese sun seems the blazing focus of the glassy ocean's immeasurable burning-glass. The sky looks lacquered; clouds there are none; the horizon floats; and this nakedness of unrelieved radiance is as the insufferable splendors of God's throne.

After Ahab makes his reading with the quadrant, he impulsively revolts against this daily exercise of consulting the heavens. He cries out,

Foolish toy! Babies' plaything of haughty Admirals, and Commodores, and Captains; the world brags of thee, of thy cunning and might; but what after all canst thou do, but tell the poor, pitiful point, where thou thyself happenest to be on this wide planet, and the hand that holds thee: no! not one jot more! . . . Curse thee, thou vain toy; and cursed be all the things that cast man's eyes aloft to that heaven, whose live vividness but scorches him, as these old eyes are even now scorched with thy light, O sun! Level by nature to this earth's horizon are the glances of man's eyes; not shot from the crown of his head, as if God had meant him to gaze on his firmament. Curse thee, thou quadrant!

Captain Ahab resolves at that moment no longer to be guided from on high. He flings his quadrant to the deck. Since he lives on the earth, from birth to death, Ahab resolves to be governed henceforth only by earthly referents. His sole guides will be his compass and his log: "no longer will I guide my earthly way by thee; the level ship's compass, and the level dead reckoning, by log and by line; these shall conduct me, and show me my place on the sea."

When Melville wrote this parable of Ahab and the quadrant, he had in mind the revolutionary Promethean spirit of the nineteenth century, when the minds of many men determined to limit their aspirations to the measurements of this world, with no reference to the insufferable throne of God.

This vertical reference is the "line" of which the Psalmist wrote, "The heavens declare the glory of God. . . . Their line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the end of the world" (Ps. 19:1,4).

Although scholars are not agreed as to the origin of the expression "dead reckoning," the combination of this noun and this adjective intimates something rather frightful. Dead reckoning is reason devoid of life, logic without logos.

The Testimony of Creation

Perhaps the most important of Touchstone's intersections is configured by a vertical line, consisting in the transcendent light from on high. By this we mean more, I submit, than simply the authority of the Bible. I make this point, because the Bible itself testifies to a prior book, the testimony of the created world.

Pope St. Gregory the Great likened "the considered appearance of Creation" (species considerata creaturae) to "a sort of reading for our mind" (quasi quaedam sit lectio menti nostrae). According to this traditional Christian view, the rationality and iconic quality of the universe, the clearly intentional disposition of its parts in relation to one another and to the whole, especially its relationship to man, is the sustaining subtext of the human narrative and the foundational context of poetry. In other words, the world is a text; it is not a scribble.

There is no need for the human being to formulate human meaning out of whole cloth. He is expected to presume, as more or less obvious, that the universe is possessed of a story line, that it is a rational and poetic place, in the sense of possessing a systematic coherence corresponding to the innate aspirations and essential structure of the human mind. The world and the intellect were made for one another.

In the vertical line of divine guidance, consequently, I include the authority of Nature, especially biology. Surely a major malaise of contemporary culture is a sustained revolt against biology. That is certainly "dead reckoning" in an extreme form, the complete divorce of bios from logos.

Prophetic Twin Opposition

And here, I submit, we detect an important place where Touchstone's vertical line crosses a political line. We agree together and contend that the political order is put in peril when it rebels against the structure of created reality, in particular the authority of biology.

We are political descendants of Edmund Burke—at least in this sense: We agree with Burke that the foundation of the political order is the unalterable biological condition of human existence, particularly the mutual relationship of the two sexes and the proper, coherent structure of the family as the source of order and the living channel of tradition.

These are the source, not only of fundamental moral responsibilities, but also of those profound emotional sentiments without which it is impossible to call a society "human." No political entity can long survive, we are persuaded, that ignores, scoffs at, or attempts to alter the human sentiments that bind husband and wife to one another, and parents and children together. The very idea of patriotism, to say nothing of the myriad political responsibilities of human beings in society, begins with the natural affections that bind a family together.

The normal and presupposed unit of the political order is the family, which Vatican II calls the ecclesia domestica. It properly consists of father, mother, and children. The family is "traditional" in the sense that it is the place where truly human existence is handed on.

The most significant aspect of the present political crisis within our liberal democracy is the biological confusion currently at work in the destruction of the American family. In this respect, let me say that Touchstone's role has been nothing short of prophetic. From its very inception, three decades ago, our editors resolved to resist two new phenomena which, to many other people, may have seemed optional, or at least not of great importance.

These phenomena were the growing popularity of women's ordination and the widespread use of artificial birth control. Our opposition to both of these things has been strong and consistent. We at Touchstone sensed very early—and have always acted on the sense—that women's ordination would corrupt the integrity of the Church and that artificial birth control would destroy the family.

I submit that the dreadful events of the past three decades vindicate, at least to our eyes, the correctness of that twin opposition. Those churches that adopted the ordination of women are in full decline, and those couples that adopt artificial birth control move from a two-percent chance of divorce to a fifty-two percent chance of divorce.

Logos & Icon

Let me further say, with respect to our opposition on these two points, that we at Touchstone have been guided, not only by the conviction of a logos, but also by the perception of an icon.

That is to say, we have been directed, in this respect as in all others, by dogmatic considerations of Christology. Just as St. John calls Jesus the Logos of the eternal Father, so St. Paul calls him the "Icon of the invisible God." We at Touchstone endeavor to be the servants of God's iconic Word. •

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on mere christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

28.3—May/June 2015

Of Bicycles, Sex, & Natural Law

Describing Human Ends & Our Limitations Is Neither Futile Nor Unloving by R. V. Young

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor