Book Review

Stalled by

An Ox

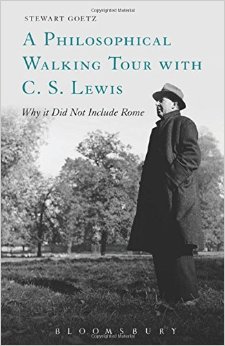

A Philosophical Walking Tour with C. S. Lewis: Why It Did Not Include Rome by Stewart Goetz

Bloomsbury, 2015

(190 pages, $29.95, paperback)

reviewed by S. M. Hutchens

Stewart Goetz's Philosophical Walking Tour with C. S. Lewis, significantly subtitled, Why It Did Not Include Rome, is another contribution, and here a credible one, to the Why-C. S. Lewis-Did-Not-Become-a-Catholic genre. There are many Catholics who have difficulty understanding why Lewis, given the depth of his knowledge and spiritual acuity, did not see or could not accept what they behold in the glory of Rome. Just what were the moral, intellectual, or perceptual defects that made Lewis remain Protestant, particularly curious in someone so highly developed in each sphere?

Catholic Answers

Near the end of the book Goetz reviews the major proposals: Lewis simply thought that "Rome was wrong" (Thomas Howard). Christopher Derrick believes Lewis had not traveled enough—that had his British parochialism been exposed to continental Catholicism, his horizons may have expanded enough to make the claims of the Catholic Church believable to him. Joseph Pearce thinks the recalcitrance came from the anti-Catholic bigotry of Ulster that penetrated to the bone and never left him. James Como postulates that Lewis avoided the truth because his vocational aspirations in the British academy, his popular appeal, and the sales of his books, would have suffered had he converted. John Randolph Willis says the problem was that Lewis "had no sense of, and no interest in history." Knowledge of the broader landscape of human events would have helped show him the significance of the Catholic Church. Goetz adds to this list that Lewis's belief in "mere Christianity," that is, the Church as he, with many Protestants, perceived it manifest among us, foreclosed any particular church's exclusive claim to universality, even Rome's, and made the Anglicanism in which he found himself during his lifetime a comfortable enough home.

The Heart of the Matter

However much there might be to any of these proposals—and Goetz is not impressed with the ones based on character flaws—he believes they have all missed the most significant reason for Lewis's forbearance:

My claim is that while [perennial Catholic-Protestant disagreements] were real issues for Lewis, their intellectual status was secondary in nature. What more deeply troubled Lewis were Aquinas's, and thus the Roman Catholic Church's, positions on the primary philosophical issues of the nature of happiness, pleasure, pain, and the soul, body, and person. These were more fundamental matters for him because they concern ideas that are conceptually presupposed by theological topics of interest to ordinary people before they encounter the Christian gospel. . . . My earlier emphasis on the fact that Lewis was first and foremost a philosopher warrants repeated stress here, particularly for those who are of an evangelical theological persuasion . . . [for] Lewis was not an evangelical of the [sola scriptura] sense. As a philosopher, he believed the mind can know something about the just-mentioned topics by means of the natural light of reason alone as it manifests itself in common sense. . . . Given his philosophical conviction about the fundamental soundness of reason, which is common to all persons prior to any initiation into theological matters, Lewis regarded theological concerns as secondary in nature when it came to assessing his difference with the Roman Catholic Church (11).

A Mildly Irritated Footnote

This would seem a convenient point to insert an excursus of which I need to deliver myself, since I have three times in about as many months encountered in the writings of learned non-Protestants this fascinating creature, the Evangelical Christian, "inclined to hold, if he does not actually believe, that knowledge about good and evil [etc.] can only be had through reading Scripture and having one's mind enlightened via an understanding of it." I must say that in my own going to and fro on the Evangelical earth I have never encountered this beast—although I have not gone everywhere, so cannot say with complete assurance that there is no such thing. Perhaps some bold apologist has actually found one out in the woods and has the head on his trophy wall.

I suspect, however, the animal has been logically but imaginatively hatched on a misunderstanding of what sola scriptura means among those who profess it—that the slogan represents an encompassing epistemological principle referring to Scripture as the sole source of valid knowledge, theological or otherwise, rather than Scripture as the defining head of authority over pope and Tradition so that, as the Articles of Religion explain, "Holy Scripture containeth all things necessary to salvation: so that whatsoever is not read therein, nor may be proved thereby, is not to be required of any man, that it should be believed as an article of the Faith, or be thought requisite or necessary

to salvation."

Note the limitation understood in this important Reformation confession on the scope of scriptural teaching—similar to those the Roman Church places on papal definitions ex cathedra: Scripture applies not to everything, but to "articles of the Faith," just as papal authority is limited to the definition of doctrine and morals. Evangelicals, with historical Protestantism in general, believe in the primacy of knowledge derived from Scripture over all extra-scriptural sources—and among Evangelicals, as among Catholics, there tends to be a rather large penumbra involved in "derivation"—and the necessity of subjecting all other knowledge to its teaching, but not that there is no valid knowledge outside of Scripture, including that concerning good and evil, happiness, and so forth. Here endeth the lesson.

The Intellectual Chasm

These considerations, however, are peripheral to the thesis of the book, which is centered in a professional philosopher's concern to show that the philosophical rather than the theological Lewis is the primary Lewis, and that his disagreements with Thomism, the official philosophy of Roman Catholicism, created "an intellectual chasm . . . that could not be bridged," so that "the Roman Catholic understanding of the Pope and the Virgin Mary merely added to an already existing deeper intellectual disagreement that Lewis had with Rome."

Goetz, with a master's grasp of both the Lewis corpus and the Aristotelian-Thomistic points of difference, illustrates the nature of the great chasm with particular reference to happiness, body and soul, and good and evil. On this last issue he indicates that Lewis agrees with the Augustinian assessment of evil as privatio boni, but adds to this an imported conviction that pain is evil and pleasure, for which we were created and of which pain is the extinction, is good—technically, he is a hedonist—so that even the pleasure a person receives in evil-doing is God's gift. (Lewis has Screwtape say that the object of the devils is as far as possible to encourage evil while removing its pleasure. In this field their largest problem is that they have not, in spite of the intensity of their researches, been able to produce even one real pleasure. All of it must be stolen, and they resent it.)

The body of the treatise is Goetz's exposition of Lewis's differences with Thomism. This is philosophy, and philosophy is difficult, but Goetz has succeeded admirably at making it as comprehensible as such writing can be to the reasonably patient and attentive non-specialist. It is difficult not to agree with him about the disagreements. What this reviewer finds a bit more problematic is something Goetz points out early on: "I can anticipate a chorus of objections from those devotees of Lewis who have read what he wrote about his disagreements with the authority of the Pope and Roman Catholic positions on the Virgin Mary [that is, on doctrinal disputes between Catholics and Protestants]. . . . My claim is that while they were real issues for Lewis, their intellectual status was secondary in nature" (11).

Hmmm . . .

The proof of a claim to the primacy of one reason for an opinion among plausible competitors must necessarily be soft, as satisfactory as a demonstration of the existence of that reason may be—as I believe it is here. The "chorus of objections" Goetz anticipates to typically Protestant theological reasons and Thomas Howard's "because he thought Rome was wrong" join force with statements like this one from Lewis in a letter to Hart Lyman Stebbins, where, emphasizing what is for him the vital importance of the mass of doctrine upon which Scripture, the fathers, the middle ages, modern Roman Catholics, and Protestants agree (one will recognize "mere Christianity" here), he continues with this very typically Protestant doctrinal definition of why he is not a Catholic:

The Roman Church where it differs from this universal tradition and specially from apostolic Xtianity I reject. Thus their theology about the [Blessed Virgin Mary] I reject because it seems utterly foreign to the New Testament. . . . Their papalism seems equally foreign to the attitude of St. Paul towards Peter in the Epistles. The doctrine of Transubstantiation insists in defining in a way [what] the [New Testament] seems to me not to countenance. In a word, the whole set-up of modern Romanism seems to me to be as much a provincial or local variation from the ancient tradition as any particular Protestant sect is. (158–159)

One must admire an author who is willing to include evidence that appears so damaging to his thesis—here that mere Protestantism of a theological more than philosophical tenor is at the foundation of Lewis's inability to convert, that Lewis was first and foremost a theologian, and that his philosophical difficulties with St. Thomas, while not unimportant, should be regarded as secondary when it comes to assessing his differences with the Roman Catholic Church—not least because the major, distinctively Roman, doctrines he could never accept, particularly those of the Marian canon, the nature of the papal office, and the identity of that church with the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church of the Creed, are concerned with disputed questions of fact—with theology—and have no necessary or logical connection to the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas. They appear to have been in Lewis's mind as insuperable bars to conversion however much or little Thomism might have added to their insuperability.

Highly Recommended

This being said, this is the most intellectually satisfying book on C. S. Lewis I have read. Because of Goetz's meticulous and respectful attention to Lewis's thought, as required for accurate treatment of his philosophical opinions, all that he says consequently about his subject bears the mark of this fair and careful reasoning. He is convincing on Lewis's differences with the received Catholic philosophy of his time; nothing in it is careless, facile, or partisan, and he blesses in particular Catholic readers who love Lewis with his conviction that inability to join the Catholic Church was based primarily on honorable difficulties with Thomism—which remains in our own day an important school, but no longer seems to function as "perennial philosophy"—rather than bigotry, provinciality, culpable ignorance, or craven self-interest.

He has not convinced this reviewer on the primacy of philosophy over basic Protestant theology in the intellectual Lewis, but at the end of the day I must say, who knows but that Goetz may be right. At least he has certainly earned his opinion fairly, and written a must-read book among a proliferation of those that aren't. •

S. M. Hutchens is a Touchstone senior editor.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor