View

Thine the Deadly Pain

Michael S. Luckey on How a Presbyterian Pastor Rediscovered the Passion

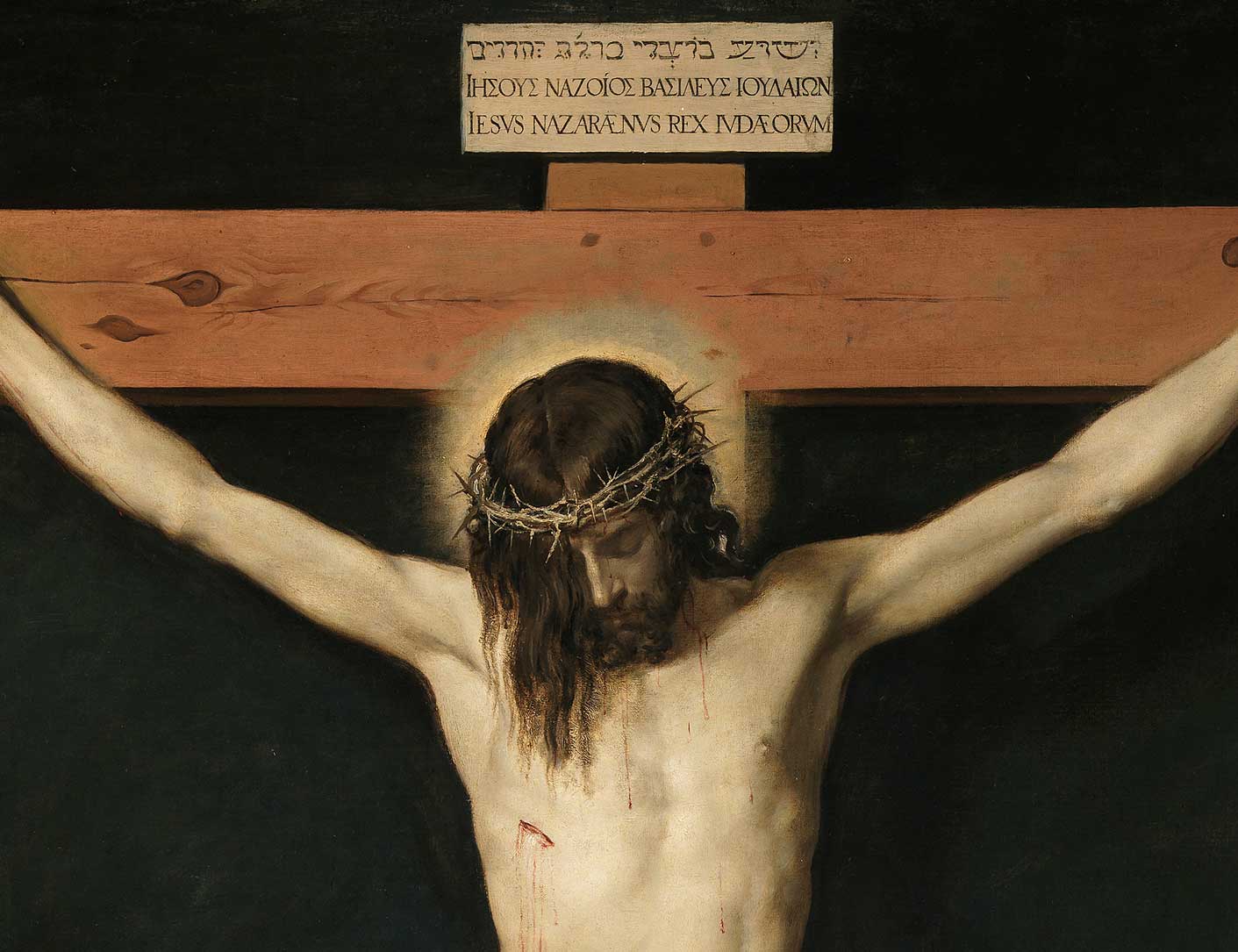

In my office hangs a large picture of the crucified Christ by the seventeenth-century Spanish artist Diego Velázquez. The picture shows a pale Christ held to a cross by four nails. He wears a crown of thorns on his head and a cloth around his waist. Blood runs from his hands, feet, and side.

For most of my twenty-five years of pastoral ministry I would not have displayed any representation of the crucified Christ. I emphasized the empty cross, the empty tomb, and the living Christ. I delighted in telling the story of a friend of mine who is a mission worker in Mexico. He and his mission team labored under the hot sun one summer, building a house for a Mexican woman and her four children. On the final day, as the house neared completion, the woman told her oldest son to go get the crucifix hanging on a wall in their old home. She also told him to bring a pair of pliers. Then, in front of the mission team, she used the pliers to pull the corpus from the cross, as she said with much emotion in her voice, "Aqui no hay Cristo muerto." ("Here there is no dead Christ.")

But in a curious reversal of the Mexican woman's testimony, I find myself taking the pliers, so to speak, and reattaching the corpus to the cross. I have come to see that knowing Jesus as the crucified Savior and as the risen Lord does not have to be an either/or proposition; it can and should be a both/and reality. To fix one's eyes on Jesus means beholding him as the Messianic man of sorrows (vir dolorum) and as the risen, victorious Lord (Christus Victor). In this vein the Apostle Paul said, "I want to know Christ and the power of his resurrection and the fellowship of sharing in his sufferings, becoming like him in his death, and so, somehow, to attain to the resurrection from the dead" (Phil. 3:10–11). Paul references Christ's sufferings and resurrection victory in the same breath.

The personal catalyst for knowing Christ more intimately through his Passion was last year's Lenten journey. My usual practice during Holy Week was to preach one sermon on the crucifixion, but last year I decided to try something different: from Ash Wednesday through Holy Week, I would focus exclusively on the cross of Christ and the suffering he endured there for sinners. I preached six Lenten sermons on different aspects of the cross of Christ. I announced to the congregation that our theme for Lent would be Paul's declaration in 1 Corinthians 2:2: "For I resolved to know nothing while I was with you except Jesus Christ and him crucified."

Catholic Resources

While preparing my sermons, I was surprised by the amount of devotional literature, both Catholic and Protestant, pertaining to the Passion. In the past, I paid little attention to Catholic writings on the Passion; I spurned resources that were non-Reformed.

I knew that Roman Catholics were people of the crucifix and that they placed much emphasis on the suffering of Christ. And I was nominally familiar with a few devotional aids in the Catholic tradition, such as the Stations of the Cross and the medieval prayer to Jesus known as the Anima Christi. I decided to read the Anima Christi slowly and deliberately. Then I reread it, even praying it. I continued the prayer, asking Christ to strengthen me by his passion and to hide me within his wounds.

Another discovery was a medieval Passion poem with Christ as its speaker. The words took deep root within me:

Man and woman, look on me

How much I suffered for you, see!

Look on my back, laid bare with whips:

Look on my side, from which blood drips.

My feet and hands are nailed upon the Rood;

From pricking thorns my temples run with blood.

From side to side, from head to foot,

Turn and turn my body about,

You there shall find, all over, blood.

Five wounds I suffered for you: see!

So turn your heart, your heart, to me.

As I turned my heart anew to Jesus, I began to read Fulton Sheen's Life of Christ. One of his insights was the assertion that Christ's life was the only life ever lived backward. Every other person who ever came into this world did so to live, said Sheen, but Christ came into it to die. "It was not so much that his birth cast a shadow on his life and thus led to his death; it was rather that the Cross was first, and cast its shadow back to his birth."

Protestant Resources

Continuing my Lenten study, I was surprised to learn how much Protestant devotional literature existed on the Passion of Christ. As I perused the internet in search of Passion devotional aids, I found treasure in the doctoral dissertation by Joseph Teller. Titled Members of Christ's Body: Christ's Passion and Community in Early Modern English Poetry, 1595–1646, Teller's work shows how extensive Passion devotion was for both Catholics andProtestants during the post-Reformation period. St. Bernard of Clairvaux, St. Francis of Assisi, and St. Bonaventure were major influences on poets and churchmen such as Robert Southwell, William Alabaster, Richard Crashaw, and John Donne. The latter spoke and wrote profoundly about the Passion; their affective and highly visual words were embraced by both Catholics and Protestants. Donne, for instance, identified with Christ's passion in a very personal manner:

So when my crosses have carried me up to my Saviour's Crosse, I put my hands into his hands, and hang upon his nailes, I put mine eyes upon his, and wash off all my former unchast looks, and receive a soveraigne tincture, and a lively verdure, and a new life into my dead teares, from his teares. I put my mouth upon his mouth, and it is I that say, My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me? And it is I that recover againe, and say, Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit.

Such vivid Passion language was not uncommon in the post-Reformation period, some of it reminding me of the graphic movie The Passion of the Christ.

As I continued to seek out godly Passion literature, I encountered a particularly arresting excerpt from a sermon by William Perkins, a Calvinist. His words are similar to the aforementioned words by Donne:

If thou wouldest be revived to everlasting life thou must by faith as it were set thy selfe upon the crosse of Christ and applie thy hands to his hands, thy feete to his feete, and thy sinnefull heart to his bleeding heart, and content not thy selfe with Thomas to put thy finger into his side, but even dive and plunge thy selfe wholly both bodie and soule into the woundes and bloode of Christ.

Daniel Heinsius, a Dutch Calvinist, prayed, "Oh let us always reflect our eyes upon thee, and let they sufferings take a deepe impression both in our Memories and in our affections." Hyperbolic descriptions such as a "crimson river" of the Savior's blood were certainly making a "deepe impression" in my memory and in my affections.

Spurgeon & Hymns

Yet another transforming Lenten encounter occurred as I read a sermon by the English preacher Charles Spurgeon. Spurgeon, a Calvinist Baptist, preached a sermon on The Wounds of Jesus. He believed that Jesus would bear the crucifixion wounds in his body for all eternity, referring to them as Christ's ornaments, glories, jewels, and trophies. The presence of Christ's wounds in heaven, he said, will stir up holy hearts in praise of the Lord. He concluded his sermon by imploring sinners:

Look at his side, there is easy access to his heart. His side is open, and even your poor prayers may be thrust into that side, and they shall reach his heart, holy though it be. Only do thou look to his wounds, and thou shalt certainly find peace through the blood of Jesus. . . . Thy wounds, oh Jesus! thy wounds; these are my refuge in my trouble. Oh sinner, may you be helped to believe in his wounds! They cannot fail; Christ's wounds must heal those that put their trust in him.

As I read graphic accounts of the Passion of Christ, my theology was undergoing a transformation: it was becoming more affective, not just cerebral. Fixing one's eyes on Jesus, per the exhortation in Hebrews 12, means to behold by faith the Lord in his many facets—as the Lamb slain from the creation of the world, as well as the risen King of kings and Lord of lords.

During my Lenten journey, I also revisited the hymnody of my Protestant tradition. Many of these hymns reference the Passion in quite poignant terms. For instance, "Rock of Ages" speaks of water and blood flowing from the wounded Savior's side; "O Sacred Head Now Wounded" speaks of the Lord's pale visage and thorn-crowned head weighed down with grief and shame; "There Is a Fountain Filled with Blood" has as its primary referent the astonishing image of a fountain filled with blood drawn from the Savior's veins; "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross" draws attention to the head, hands, and feet of the Lord, from which sorrow and love flow; and "Beneath the Cross of Jesus" refers to the "dying form" of the suffering Savior. Numerous other hymns allude to the Passion of Jesus.

Moreover, not a few English and European churches depict the five wounds artistically: the pierced heart of Jesus is set on a cross, surrounded by what look like the severed hands and feet of the Lord. On Orthodox crosses, Christ is depicted with four nails holding him to the cross (with each foot nailed separately), while Catholic crucifixes depict him with three nails (one nail piercing both feet). The five wounds of Christ are represented on the national flag of Portugal, and in the Philippines there is a Catholic shrine dedicated to the five wounds.

Laudable Goal

Embracing the Savior's wounds affected my faith; it was no longer so sanitized and cerebral. For some time past, my faith journey had been primarily a doctrinal exercise, while my first love cooled. But during my Lenten journey I found my heart strangely warmed again, as I discovered in greater depth that the heart of the Christian faith is an incarnate Savior who entered into the realm of flesh-and-blood humanity; a suffering Savior who bled and died in making the atoning sacrifice for sinners; a living, scar-bearing Savior who can be deeply known and loved.

The picture of the crucified Christ in my office remains as a powerful visual reminder, to me and to all who enter, that Christ suffered, bled, and died for sinners. For this Evangelical Calvinist, knowing Jesus Christ and him crucified is profoundly scriptural. The same Lord calls pastor and parishioner alike to lives of mortification and vivification. At the Cross we are invited to pursue the laudable goal (in good Evangelical parlance) of seeing him more clearly, loving him more dearly, and following him more nearly. •

Michael S. Luckey is a Presbyterian minister and Alamo history buff from Texarkana, Texas. Married with two children, he holds a D.Min. from Beeson Divinity School.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on ministry from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor