Feature

The Augustinian Luther

A Pilgrimage in Search of the Reformer's Spiritual Director

Fifty years ago, in a pastoral theology class, my instructor said that conversion involves God working through personal relationships—in a conversion experience there is another human person involved. I was intrigued and asked who that person was in the case of Martin Luther. He responded immediately, "Johannes von Staupitz."

Thus began my lifelong interest in von Staupitz and his relationship with Luther. Half a century later, in late 2011, I set out on a research trip to explore their relationship. My friend and classmate, Dr. David Jordahl, who now lives in Germany, agreed to be my traveling companion and fellow explorer. We planned to go ad fontes as participants and observers in worship, historical study, and conversation about Luther's roots as an Augustinian friar.

Our pilgrimage would take us to Salzburg, Austria, and Würzburg, Germany, both important Roman Catholic centers with historical significance for Luther scholars. The Augustinian friary in Würzburg is the official center of the German Augustinians today and an outstanding place for research on Luther and von Staupitz as Augustinians. St. Peter's Benedictine Archabbey in Salzburg, the oldest monastery in German-speaking Europe, is the burial site of von Staupitz.

The Augustinians

As an Augustinian, Luther was a friar, not a monk. Monks (Cistercians or Benedictines, for example) live in monasteries and are devoted to contemplative prayer, while friars (Augustinians, Dominicans, Franciscans) combine regular prayer with active service in church and society. When he entered religious life, Luther chose the Augustinian friary from among a great variety of monasteries and friaries in Erfurt, the city where he had attended university. It was the largest friary there, with the best library and many well-educated friars. Since the thirteenth century, the Augustinians had held the professorship of theology at Erfurt University.

Even so, Luther must have stood out, already having a Master of Arts degree when he became an Augustinian. His later writings and hymns indicate that he was gifted in both German and Latin. He came from a family of "money nobility": his father came to the Erfurt friary for Luther's first Mass with 25 horsemen and a generous financial gift.

Luther was a devoted Augustinian, living with the Augustinians during his formative theological years (seminary, graduate school, first professorship). He wore his Augustinian habit daily, right up to his marriage. In their life and work, the Augustinians stressed theological scholarship, Bible study, preaching, and pastoral care. As a young friar, Luther was famously influenced by St. Augustine, but also by St. Bernard of Clairvaux, whose thought was experiencing a renaissance among Augustinians.

Luther's novice master was Johannes von Greffenstein, who would have been at least as influential on Luther as von Staupitz, since he would have overseen Luther's progress in the life of a friar. But von Staupitz was Luther's spiritual director. When a theology faculty was established at Wittenberg, von Staupitz was given the chair, and he was determined that Luther would succeed him in that position.

Luther was ordained in St. Mary's Cathedral in Erfurt. He was not a parish priest as we use the term today, but became a preacher, liturgist, and confessor at St. Mary's Church in Wittenberg, as well as a professor at Wittenberg University.

When the pope ordered the head of the Augustinian order to silence Luther, it fell on von Staupitz to carry out the command. But because von Staupitz was sympathetic toward Luther, he creatively chose instead to release Luther from his vow of obedience.

Not many years later, when the Reformation had decimated German Augustinian friaries, von Staupitz went to Salzburg, where he had once been responsible for the supervision of an Augustinian friary and knew the archbishop. He requested permission from the pope to be released from the Augustinian order to join the Benedictines. The pope granted his request, and von Staupitz became a monk, attached to St. Peter's Archabbey in Salzburg. He was also appointed preacher at Salzburg Cathedral, and eventually became abbot of the monastery.

During this time, he continued to correspond with Luther, and he even invited Luther to come to Salzburg for a visit. Unfortunately, he died before Luther was able to come. He is buried in a side chapel of the abbey church.

Salzburg's Benedictines

On December 31, 2011, Dr. Jordahl and I arrived in the Salzburg Old City, at the abbey square. It was a short walk to the Franziskanerkirche, where von Staupitz sometimes preached. The church is Romanesque, with a large Baroque altar area added. Just around the corner from the Benedictine abbey, there is a Franciscan monastery.

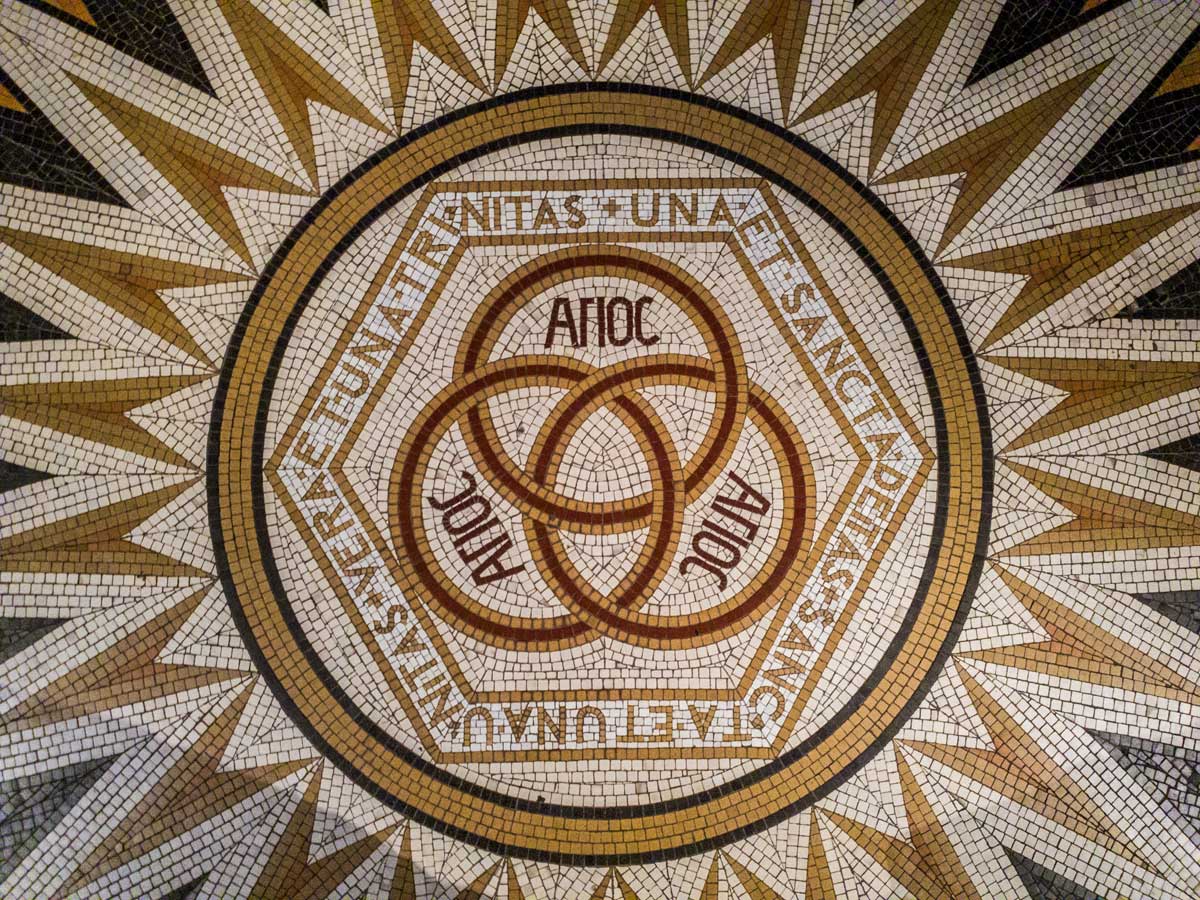

It was only a few more steps to the cathedral and square. Founded by Irish missionaries in the eighth century, the cathedral was first Romanesque, then Gothic, and finally, after its eighth fire, it was razed and rebuilt Baroque. It was once the largest Christian church north of the Alps. At the transept there are four organs positioned high above the aisles, plus a great organ in the rear balcony, so five organists are needed for major feast days, along with choirs.

We were greeted at the archabbey doors by Pater Karl, a permanent deacon. He showed us the complicated route through the monastery to our spacious, spotless guestrooms. Pater Karl pointed out that, though in his forties, he was the youngest monk of the abbey, whose numbers had declined from 33 monks to thirteen. But this monastery has existed for 1,300 years, enduring through various regimes, wars, and upheavals, so they were not too concerned.

Worship began almost immediately after we had located our rooms. We went to the great abbey church, where the abbot himself gave us the liturgical materials for the office of terce. The monks prayed in their stalls, we and the other visitors in the pews.

Afterwards, Pater Michael, the guestmaster, took us to the magnificent grave of "Doctor Johannes von Staupitz." It was right in the middle of the chapel floor, beneath a red marble slab. Pater Michael pointed out that the sanctuary of this chapel is the oldest structure in Salzburg. Von Staupitz deserves this place of honor, it seems, because he is regarded as the greatest of the ninety abbots of this still significant monastery.

We had arrived at an extremely busy time of the church year. The archabbey is famous for its New Year's Eve service. We were advised to come half an hour early, but even then the church was packed. Thanks to Jordahl's persistence, we found two seats in the monks' choir near the altar and lectern.

This Catholic liturgy had a strongly Lutheran character: Bach's music was prominent, a quote from Dietrich Bonhoeffer was printed on the back of the bulletin, and all the hymns sung could be found in the Lutheran Service Book, including "Grosser Gott." This also was the first time I experienced an authentic "Silent Night": an Austrian hymn sung by Austrians and played by an Austrian organist in almost folk-music style—slow and moving. It was snowing outside, just as on that Christmas Eve when it was first sung.

New Year's Day

Considering that the Austrians were celebrating New Year's Eve all night, it seemed a minor miracle that anyone would be at church on New Year's Day. But the Mass was surprisingly well attended. The abbot had preached on New Year's Eve, so on New Year's Day Pater Karl was the preacher; both were outstanding.

After Mass, we were invited to dine with the Benedictines, and I had an opportunity to converse with Pater Karl, who was seated on my right. He made no secret of his respect for Martin Luther—his only critical remark was about differences regarding the Apocrypha. Pater Karl's diploma thesis had dealt with the theme of "community" in Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who maintained that the central orientation of monasticism was not flight from the world but joining a community—better expressed in German by the word Gemeinschaft. Perhaps this had been one of Luther's motivations for joining the Augustinians.

Following the meal, coffee was served in an adjacent room, where we were honored by being placed next to the abbot. In fluent English, he described the recent multi-million-dollar renovation of the monastery. He was also more open than we were about the problems of our respective churches.

After a Latin vespers service, we were served a fine evening meal. Soon the Benedictines had to gather for compline, so we retired to our rooms. We had just enough time to present Pater Michael with a copy of the Lutheran Service Book and to show him its notation of the commemoration of Johannes von Staupitz on November 8 of each year. He said it would receive a place of honor in their library.

The next morning, January 2, both Pater Karl and Pater Michael came to bid us goodbye, exchange calling cards, and present us with some large photographs of the chapel.

To the Library

We then headed by train for Würzburg (but made two stops along the way, at the Lutheran towns of Nuremberg and Neuendettelsau; see page 38). In Würzburg, our final pilgrimage stop, with its strong Roman Catholic tradition, we faced our own Lutheran past from an Augustinian perspective. We walked from our hotel to the Bibliotheca Augustiniana, a center for research on Augustine and the Augustinian order.

Dr. Carolin Oser-Grote greeted us at the door. Glancing behind her, we saw a large poster of Martin Luther as a young Augustinian. Down the corridor we saw more portraits of the youthful Luther, one of them hanging next to a similar portrait of Johannes von Staupitz. These Augustinians have neither let go of Luther nor relinquished von Staupitz to the Benedictines. The latter's mark on church history was primarily as an Augustinian.

We were soon paging through the collected works of von Staupitz, published in volumes with German and Latin on facing pages. Exhibited in a prominent place were Franz Posset's The Real Luther and The Front-Runner of the Catholic Reformation: The Life and Works of Johannes von Staupitz. Dr. Oster-Grote had to remind us eager American Lutherans that the Bibliotheca Augustiniana housed material not only about Luther and his fatherly friend, but also about St. Augustine.

We were faced with row upon row of books in numerous languages comprising the works of St. Augustine and the efforts of his commentators. It is well known that this church father was a wide-ranging thinker, and consequently, the library is utilized not only by theologians but also by historians, psychologists, and linguists. Spacious and secluded desks are available for visiting scholars.

Already a bit dazzled and humbled by the challenge this library presented, we were further impressed by the Zentrum für Augustinusforschung on the next floor, where Dr. Andreas E. J. Grote, Carolin's husband, showed and described to us the massive volumes of the Augustinus Lexikon he is editing. These volumes in German contain the finest scholarship on Augustine's thought.

The combined scholarship of this couple, who spoke to us in conversational English, reminded us of the limits of our own scholarship in the field, so we posed our questions carefully. We were rescued when the church historian and Luther expert Pater Dr. Michael Wernicke appeared to help us make the most of our time.

Confrere Luther

Setting the tone for the following hours of discussion and fellowship, Pater Wernicke greeted us with a hearty reference to his confrere Martin Luther. He used this French term frequently, perhaps because, as an Augustinian, he had a different, more intimate, relationship to Luther than we "secular" pastors and scholars. After all, Luther continued to wear the Augustinian habit for some years even after his break with Rome, and he spent his life in an Augustinian friary, to which he then held the deed.

Recent Roman Catholic scholarship on Luther, particularly that of Franz Posset, maintains the traditional Augustinian emphases on biblical scholarship, preaching, and Seelsorge (pastoral care of souls), which all sounded rather Lutheran to us. Seelsorge, of course, cannot be separated from confession and absolution.

The Augustinian church is at the best address in Würzburg. People attend Mass there all through the week and confessions are regularly heard. The church had just completed a prolonged renovation, including a new counseling and confessional area. As in Luther's day, the Augustinians hear confessions from people coming in off the street, and they are sought-after confessors—sometimes there is a waiting-line. A separate office for counseling is located on the street side of the friary.

We had previously decided to bring up the subject of confession, which Pater Wernicke elaborated on in both a practical and a theological manner. Our Lutheran seminary education had given us no guidance at all on conducting confession—while at the same time recommending it!

Perhaps his most interesting comments regarding confession were those about empathy as the primary thing. The sticklers with scruples (think of Luther) remain a pastoral problem, and it is essential that the father confessor go to confession himself, in part because of the burdens the confessions place upon him.

That evening we shared a come-as-you-wish supper with the friars, and continued visiting. We learned that Pater Michael had spent 16 years in Rome as an Augustinian priest and scholar. He spoke English effortlessly, not hesitating to broach even some controversial themes, but always with empathy. He acknowledged that Luther retained the Catholic doctrine of the Eucharist—"This is my body; this is my blood" is basic to us to Lutherans—but did not accept the authority of the Bishop of Rome or the apostolic succession of bishops. We did not mention that the U.S.based Society of the Holy Trinity (to which more than 200 Lutheran pastors belong) restates a goal of the Augsburg Confession in its Rule: reconciliation with the Bishop and Church of Rome. Perhaps that's because we were also aware that the ELCA and other Lutheran churches are erecting new barriers to ecumenical progress, which we preferred not to broach.

Where He Stood

The next morning, January 4, we shared an informal breakfast with a larger group of friars. Although engrossed in discussion, we soon had to leave for our city tour, which was to take us to the very spot where Luther stood in Würzburg in 1518.

Pater Michael, who likes to relate church history through human stories, told us that when Luther came to Würzburg from Wittenberg, on his way to a disputation in Heidelberg, he was accompanied by a bodyguard. The bishop invited Luther, already a famous man, to his residence—a castle still visible from the streets of the town—and offered Luther a new bodyguard. But it so happened that Augustinians from Erfurt had come by coach with a bodyguard, and Luther proceeded with them on to Heidelberg. Pater Michael was very concerned that we should stand exactly where Luther himself stood that April day in 1518.

Pater Michael had been given a recent Sunday service bulletin from a Lutheran parish in California, causing him to react with surprise, "It is the same Mass we have!" One of us replied, "It is the same church," which Pater Michael repeated thoughtfully, but probably critically. Critique was more apparent when he saw the Eucharistic Prayer for the service, recognizing that it was something someone had written and was not one of the authorized Eucharistic Prayers of the church. We thought back to our seminary days when official Eucharistic Prayers were causing chaos in some quarters of U.S. Lutheranism.

Again we were the guests of the Würzburg Augustinians for the main meal of the day, served around noon. Prior to the meal, there was a reading from the corner lectern. Since most of the friars were present, we were introduced more formally. We talked about their university in the U.S., Villanova, and an Augustinian parish church in Los Angeles. Someone made a mildly critical comment about a pastor being away from his parish at this time in the church year—something they would not allow.

Then it was back to Bibliotheca Augustiniana to say our good-byes, but no one was there. Later we received an email apology with well-wishes for our trip and further studies. One friar guessed that our visit might lead to a book.

The Same Care

Back in a high-speed train, we were quiet, thinking over the things we had learned on our trip, and knowing it would take a long time for us to digest all that we had seen and experienced.

We had asked Pater Dr. Wernicke if Martin Luther regularly celebrated Mass in Wittenberg. Reviewing Protestant sources before our trip, we had been struck that they spoke solely of Luther's preaching. Unquestionably he celebrated Mass, came the quick answer, because he was a friar who had religious fervor. Indeed, Luther composed his own revision of the medieval Latin liturgy (Formula Messae) in 1523, and a German Mass (Deutsche Messe) in 1526.

Today, both St. Mary's Church in Wittenberg and St. Augustine's Church in Würzburg provide the same pastoral care—hearing confession, preaching, and celebrating Mass—for which Martin Luther and Johannes von Staupitz, his spiritual "father in Christ," shared such concern.

Viewing Luther and von Staupitz from a contemporary Augustinian viewpoint had been enlightening for Dr. Jordahl and me. The answer to my question in class fifty years ago now had more meaning. We had been participants and observers in worship, historical study, and conversation in the places where these two men, their confreres, and their descendants, have served the one Lord. •

A Lutheran Side Trip

I am a product of the old American Lutheran Church. I have never been to St. Sebald Lutheran Church, in St. Sebald, Iowa, the Mother Church of the Iowa Synod, but I had the opportunity to see the original St. Sebald Lutheran Church in Nuremberg. Behind the main altar is the huge shrine of St. Sebaldus, the patron saint of Nuremberg. The church is a grand example of "Conservative Reformation."

Another example is Nuremberg's famous St. Laurentius Church. This is a Gothic church undamaged by iconoclasm, with grand Marian art, side altars with linens, and a huge tabernacle. The Reformed citizens of Nuremberg thought it senseless to destroy all the sacred art they had commissioned for it, so it is still there to inspire worship today.

Both churches were streaming with tourists, including families with children, enjoying holidays in the best sense. If all the sacred art had been destroyed during the Reformation, I wondered, how many modern pilgrims would be coming to these churches today?

In Löhe's Village

After a walking tour of Nuremburg, we took a local train to the village of Neuendettelsau. There was not much doubt as to who had brought us here: Wilhelm Löhe. He became pastor here in 1837, at age 29, and never left the village before his death in 1872. The local train station is now also a museum in his honor. He founded two mission schools in America, and was also a founding sponsor of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod.

We were driven to the Hotel Gasthof Sonne, where Löhe founded the deaconess movement in Lutheranism, which a plaque on the building commemorates. The historic hotel remains intact, but it has been expanded into a modern conference hotel.

Across the street stands Löhe's parish church, St. Nikolai, enlarged and altered from its original state. Inspired, we became immersed in the story of Neuendettelsau and could visualize ourselves attending the next International Löhe Society Conference here, scheduled for the summer of 2014.

In the evening we visited Löhe's grave. We also drove by the Augustana-Hochschule, a theological seminary of the Bavarian Lutheran Church. We were told that Löhe's influence is increasing there after a period of neglect which was perhaps due to the predominance of the theology of Karl Barth in postwar Germany.

The Deaconesses

On January 3, we did a walking tour that included the cemetery where the deaconesses are buried. There were 1,300 deaconesses in the 1930s; now there are only 115 (six active and the rest retired). Few women today seem prepared to dedicate themselves to a communal life, which in practice for these deaconesses includes commitment to the spiritual disciplines of celibacy, obedience, and poverty.

We attended the noon office at St. Laurentius Church, the deaconesses' church, where morning and evening prayer and compline are prayed daily. Here we experienced something of the same liturgical and devotional spirit as at St. Peter's Archabbey.

Some ten or more pastors are active in this diakonie center. On occasion, they wear albs and stoles, an innovation certainly in the spirit of Wilhelm Löhe, who dared to insist on the proper care of communion vessels and the covering of the altar with paraments. Löhe was sometimes accused of being "Catholic." Though the word was not intended to be flattering, perhaps he appreciated the deeper meaning of it, and did not mind.

—William R. Hampton