From Modernity To Auschwitz

The Secular & Anti-Christian Origins of the Holocaust

by Joe Keysor

In his lengthy book The Holocaust in Historical Context, Steven Katz of Boston University links biblical Christianity to the crimes of the Nazis. While Katz recognizes the obvious fact that the Nazis were not Christians—that they were, in fact, hostile to Christianity—he still claims that centuries of Christian-inspired hatred of Jews, derived from the Bible, contributed indirectly but significantly to the murder of six million Jews. Christianity is thus blamed for creating a reservoir of hate that the non-Christian Hitler skillfully exploited.

Anti-Semitism is so far removed from all fundamental biblical teaching that we must reject any attempt to use it to impugn the gospel of Christ. While many such accusations arise from hostility to Christianity and a desire to disparage it at every opportunity, there may be a deeper and a subtler motive at work. Zygmunt Bauman describes this motive in his thoughtful book Modernity and the Holocaust as a desire to avoid the fact that the Holocaust was a product of modernism—a troubling thought that calls into question the entire modernist project.

If the secularists can, to a significant extent, blame the brutalities of Nazism on religion, then they do not have to confront Bauman’s claim that “the Holocaust was a characteristically modern phenomenon that cannot be understood out of the context of cultural tendencies and technical achievements of modernity.” Pointing at religion thus becomes (as he says) merely one way “to belittle, misjudge, or shrug off the significance of the Holocaust”—and the dream of modernity as progress guided by independent human reason remains untarnished.

If, however, we are not wedded (or chained?) to the modernist paradigm, if we do not feel obligated to defend our beliefs in the goodness of human nature, in the power of reason to order and improve society, and in the benefits of freedom from divine law—if we do not see Hitler’s crimes as a religiously influenced deviation from an otherwise sound modern secular outlook—then we can consider the horrors of National Socialism in a different light.

A New Anti-Semitism

The eighteenth century saw the emergence of a powerful intellectual movement that denied the need for divine revelation and boasted of the power of unaided human reason to create a better world. Optimistically named “the Enlightenment,” this movement originated primarily in France, but was eagerly received in Germany as well. It was this “Enlightenment” that introduced a new and different way of looking at the Jews—one based on human reason—which became integral to German anti-Semitism in the following generations.

The secular thinkers of the German “Enlightenment” (Aufklaerung), of whom we may take Immanuel Kant as a prime example, were not concerned about God’s wrath on the Jews for their rejection of Christ. Such a concept of God was alien to them. Their concerns were very different, and their increasingly strident objections to Jews were different. To begin with, it was the concept of Judaism itself, as secular thinkers found it in the Torah, that offended them. A God of one nation only, who imposed all sorts of stifling rules and regulations, who rewarded obedience with material blessings and visited severe punishments for various sins, was anathema to those who, like Kant, felt that human civilization had outgrown the need for such divine tutelage. Moreover, verses such as Genesis 28:20–21 were used to show that the main concern of the Jews was selfish advantage and material benefit, not a disinterested love of truth for its own sake.

Related to the charge of selfishness and materialism was Kant’s accusation that the Jews had no real emphasis on the afterlife. Missing clear references in the Jewish Scriptures to an afterlife (such as Isaiah 51:6 or Daniel 12:2–3, to name only two), Kant accused the Jews of being concerned with this life only. As he wrote in Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone, “since no religion can be conceived of which involves no belief in a future life, Judaism, which, when taken in its purity, is seen to lack this belief, is not a religious faith at all.” Thus, when Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf, “he [the Jew] lacks idealism in any form, and hence belief in a hereafter is absolutely foreign to him,” he was not expressing ideas derived from the older, religious anti-Semitism, but from a newer tradition (by Hitler’s time, such arguments were widely diffused throughout the culture).

Furthermore, the obstinacy with which the Jews clung to their outmoded beliefs in defiance of Western civilization’s obvious progress was taken by Kant as evidence that the Jews were an inferior people, isolated from essential aspects of the human experience, and even from basic human feeling. Jewish participants in the “Enlightenment,” such as Moses Mendelssohn, who might have been embraced by Kant, were later accused by more extreme anti-Semites of merely copying, or feeding parasitically off of, the superior Western civilization to which the oriental Jews would forever be outsiders.

Kant’s contribution here is too little appreciated. This dominant figure of secular and enlightened German culture was deeply hostile to the Jews, and his influence during the following century was great. As Paul Lawrence Rose wrote in Wagner: Race and Revolution, “Kant’s basic ideas were elaborated into a historical and philosophical critique of Judaism that until very recently commanded virtually unquestioning support in German culture.”

Kant was not a racial anti-Semite—that twist would emerge later in the nineteenth century—and no doubt he would have vehemently repudiated later excesses; but Michael Mack’s book German Idealism and the Jew: The Inner Anti-Semitism of Philosophy and German Jewish Responses demonstrates Kant’s contribution to a new way of thinking about Jews. This rational, philosophical anti-Semitism was to be carried on, amplified, and intensified by such later thinkers as Fichte, Schopenhauer, Wagner, and H. S. Chamberlain (the last two of these have been consistently linked to Hitler).

Kant’s ethics are also relevant to this topic. His famous Categorical Imperative, which sought a rational rather than a divine basis for ethics, can readily be adapted to different situations. Thus, it could be reasoned: “Jews are a menace to humanity. If everyone did as I did and killed Jews, society would benefit. Therefore, killing Jews is ethical.” This sort of thinking was not Kant’s intention, but once the barriers of divine law and judgment are removed, anything is possible. In the words of Christian apologist John Montgomery, “Kant separated ethics from theology, morals from God: this he believed to be one of his greatest contributions; in fact, it was one of his greatest mistakes” (Tractatus Logico Theologicus).

Parenthetically, Kant was also a racist; he openly declared that “humanity is at its greatest perfection in the race of the whites” (Physical Geography). He first strongly condemned war, but then qualified his condemnation by stating that, at our present level of development, war was a necessary agent of progress and had certain cultural benefits (a vital element of later German militarism). This was in An Answer to the Question: “What Is Enlightenment?”—a book that also disparaged English democracy as a fraud and extolled the greater freedom enjoyed by Germans under the authoritarian Prussian kings. This concept of finding real freedom by obeying the leader readily lent itself to harmful extremes.

Kant dismissed traditional religious faith as “laziness and cowardice” and called on people to have the courage to walk by reason alone. But there were disturbing aspects to Kant’s peculiar brand of “rationality”—aspects that were to be added to and developed in ways he himself could not have imagined.

Jewish Christianity

Kant was outwardly respectful of Christianity, even as he denied its central teachings, but German thinkers were to become increasingly hostile to Christianity’s un-Germanic and unenlightened values as the century progressed. Arthur Schopenhauer, for example, writing mostly in the first half of the nineteenth century, condemned belief in divine revelation as childish (Religion). He also objected to Christianity’s Jewish influence on Europe.

Schopenhauer wrote in The World as Will and Idea that “it is to be regarded generally as a great misfortune that the people whose culture was to be the basis for our own were not the Indians or the Greeks, but these very Jews.” In his view, the arbitrary separation of mankind from the animal world by the myth of a divine creation was especially harmful. “Christianity contains, in fact, a great and essential imperfection in limiting its precepts to man, and in refusing rights to the animal world. . . . Such are the effects of the first chapter of Genesis, and, in fact, of the whole Jewish conception of nature” (Religion).

Raising Kant’s objection that the Jews were materialists incapable of any spiritual life, Schopenhauer also claimed that the Jews had corrupted sound Christian teachings that had first originated in India. Moreover, he described the Jews as “a sneaking dirty race afflicted with filthy diseases,” and saw them as an obstacle to Germany’s moral and cultural development. He thought that Judaism should be eliminated, but this was to be accomplished by assimilation, so he advocated granting civil rights to the Jews, thinking their merging with the larger society would lead over time to their disappearance.

That Christianity was Jewish in origin and character and that it was incompatible with the supposedly stronger and healthier values of pre-Christian German paganism became dual pillars of an increasingly common theme. Paul Lagarde, an influential leader of the racist, imperialistic, and militaristic Völkische Bewegung (the Folkish movement) in pre-WWI Germany, sought to purify an originally Indian “Aryan Christianity” of its later Jewish accretions, and saw traditional Christianity (along with pacifism, democracy, and liberalism) as corrupting the purity of the German soul. Lagarde saw Jewish/Christian influence as totally incompatible with Germany’s spiritual mission to lead the way in the upward progress of mankind, and called for the Jews to be exterminated.

Julius Langbehn, a best-selling author and also a leader in the the Folkish movement, saw the Jews in the same way. He equated them with disease and also advocated that they be exterminated. These views were not mere eccentricities, but became increasingly popular in certain segments of the German intelligentsia. Historian George Mosse, quoting Fritz Stern, writes, “[A] thousand teachers in republican Germany who in their youth had worshipped Lagarde or Langbehn were just as important in the triumph of National Socialism as all the putative millions of marks that Hitler collected from the German tycoons” (The Crisis of German Ideology: Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich).

The most extreme statement of this hostility to Jewish Christianity can be found in Nietzsche’s book The Antichrist. There we read, after a long and bitter blast against the falsehood, dishonesty, cowardice, and corruption of Christianity, that it is essentially a Jewish religion: “the Christian church, put beside the ‘people of God,’ shows a complete lack of any claim to originality” (section 24); “the small insurrectionary movement which took the name of Jesus of Nazareth is simply the Jewish instinct redivivus” (27); “in primitive Christianity one finds only concepts of a Judaeo-Semitic character” (32); “One would as little choose ‘early Christians’ for companions as Polish Jews. . . Neither has a pleasant smell” (46). He dismissed Christians as “little super-Jews, ripe for some sort of madhouse” (44), and added, “The Christian is simply a Jew of the ‘reformed’ confession” (44).

Nietzsche went on to claim that Christianity was a Jewish plot, cooked up by the rabbi Paul as a means of undermining the Roman Empire and enslaving stronger and morally superior people with groundless fears of sin, conscience, the Day of Judgment, God, and other such Jewish tricks. These ideas are found in sections 22, 24, and 43, to name only three of many places where these themes are harped on at length. “To the sort of men who reach out for power under Judaism and Christianity—that is to say, to the priestly class—decadence is no more than a means to an end. Men of this sort have a vital interest in making mankind sick” (24). In this passage Nietzsche calls the Jews master manipulators of decadence. “Precisely for this reason the Jews are the most fateful people in the history of the world: their influence has so falsified the reasoning of mankind” (24).

While Nietzsche disdained religious, conventional, bourgeois anti-Semitism, The Antichrist makes his personal version of anti-Judaism very plain—and it is significant that while Nietzsche and Hitler were obviously different in many ways, their views of Christianity were identical. In his Table Talk, accepted as genuine by historians, Hitler referred to Christianity as a Jewish invention, a rebellion of the weak against the strong that led to the collapse of the Roman Empire, invented by the apostle Paul (who falsified Christ’s teachings). Like Nietzsche, Hitler saw Christianity as against natural law, a force for social disintegration, a religion of failures and losers, contrary to science, and a device for priests to hold power over people (for the sake of brevity quotes from Nietzsche on these and yet other points have been omitted).

Robert Wistrich’s comments in Hitler and the Holocaust: How and Why the Holocaust Happened are insightful here. He writes that Hitler blamed the Jews for unhealthy and unnatural Judeo-Christian ethics, which he saw as the prime source of “contemporary teachings of pacifism, equality before God and the law, human brotherhood and compassion for the weak, which Nazism had to uproot.” Unfortunately, too few people realize that hostility to Christianity was a key element in the concept of Jews as destroyers of culture and deadly enemies of the German people.

Contempt for Human Life

When the biblical teaching of the immortal human soul created by God is lost, the devaluation of human life is inevitable and inescapable. This trend was already evident in German philosophy in the first half of the nineteenth century, and it found clear expression in the philosophy of Hegel (though Fichte, Schopenhauer, and others could also be mentioned in this context).

The introduction of Darwin’s theories greatly accelerated an already existing trend (Schopenhauer asserted in The Horrors and Absurdities of Religion that “man is at bottom a dreadful wild animal . . . man is a beast of prey”) because Darwinism gave scientific approval to the belief that the individual was insignificant, a mere speck in a vast and remorseless progression in which only the survival and advancement of the species mattered.

Many German thinkers went far beyond the acceptance of Darwinism merely as an explanation for life as we know it, and used the revolutionary new theory as a basis for ethical and philosophical speculation as well. The clearest single example of this trend (though many others could be named) is the German biologist Ernst Haeckel. A tireless propagandist for Darwinism, he ridiculed Christianity as outmoded superstition and presented scientific rationalism as the only sure path to truth.

His attempt to follow the logical implications of Darwinism for human ethics led Haeckel into deep and troubled waters. For one thing, he concluded that “the struggle for life” was the iron law of existence (this in his best-selling book The Riddle of the Universe). This struggle was morally blind, indifferent, and knew only survival or extinction. By a swift sleight of hand, Haeckel elevated this struggle from the level of biological species to that of nations and races. Thus, if a stronger country seized territory from a weaker one, or a stronger race replaced a weaker one, or even exterminated it, this was nothing but a manifestation of the survival of the fittest, evolution being worked out in our own day and time.

This fit naturally with the concept of racial purity. As the French thinker Arthur de Gobineau argued in his book Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853–1855), racially pure peoples rose and dominated impure ones. When dominant races became infected with blood from inferior races, they sickened and declined. Gobineau’s book had a significant influence in Germany (he identified the Aryans as the most advanced and superior race), and the purity of German blood became a matter of national survival (a theme elaborated upon by a number of German thinkers).

The individual personality was lost in great evolutionary schemes stretching out over eons, and Haeckel claimed that the human “soul” disappeared at death, being merely an aspect of physical existence. Free will was also denied; there was only the law of nature, to which humans were bound just as much as the animals (humans were animals). Christian ethics were dismissed as based on unscientific mythology, and if animals or people starved or perished miserably, this was merely the natural state of affairs, a necessary aspect of the evolutionary process. To resist this was contrary to nature; as Nietzsche said in The Antichrist, “Pity thwarts the whole law of evolution, which is the law of natural

selection” (7).

Individual human life was of little or no value. As Haeckel wrote in his Riddle of the Universe, human nature “has no more value for the universe at large than the ant, the fly of a summer’s day, the microscopic infusorium, or the smallest bacillus.” Not surprisingly, Haeckel was an early advocate of euthanasia, and felt that useless burdens on society, such as defective infants, the insane, or the incurably ill, should be killed. Surprisingly, and seemingly inconsistently, Haeckel endorsed the Golden Rule, though he derived its validity not from God, but from evolution, which mandated social cooperation for the survival of the group. The rule of love and kindness did not apply to enemies outside the group, however, nor to those within the group who were useless or defective.

Haeckel had a strong sense of hierarchy, and while human life as a whole was worth little, some people were higher on the evolutionary scale and so worth more than others. At the top were the white Europeans, especially the Germanic peoples. European colonialism was thoroughly justified: the stronger and more advanced ruled by the right of evolutionary law, and the lives of primitive and backward Asian and African peoples were worth less than the lives of Europeans.

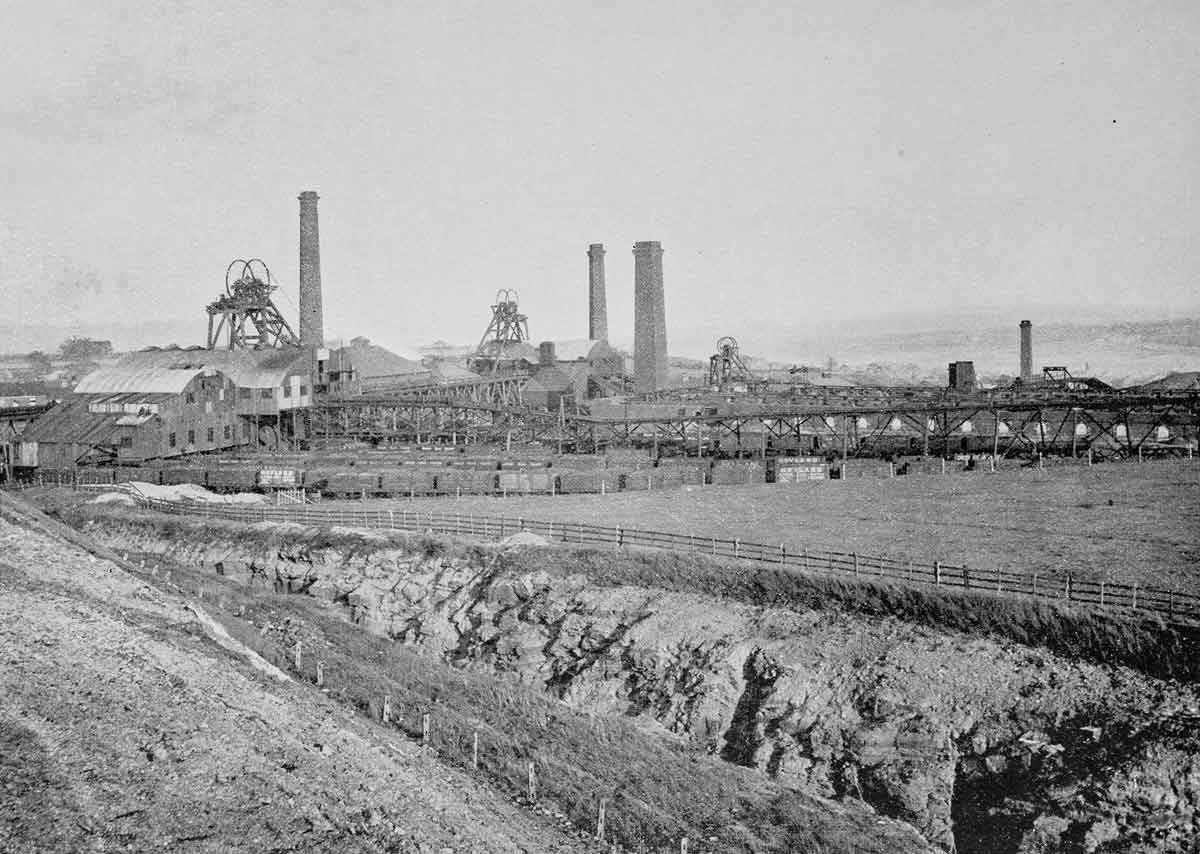

This provided a scientific justification for militarism and imperialism, and Haeckel was not slow to make the connection. He felt that a German victory in World War I, with substantial territorial acquisitions, was the solution to Germany’s shortage of “living space,” and his exhortations to German soldiers to fight and die bravely for the Fatherland provide an interesting example of secular Darwinist militarism. This, combined with his belief in political authoritarianism (nature shows us the rule of the strongest and the best, not parliamentary squabbling), make Haeckel an exemplar of how ideas that seem obviously wrong to us could have been respectable and widespread fifty years and more before Hitler came to power.

Haeckel’s ideas have been presented only briefly here; much more could be said. Richard Weikart’s book From Darwin to Hitler: Evolutionary Ethics, Eugenics, and Racism in Germany describes in detail the impact of Darwin-based philosophizing on the German intelligentsia, and shows how well-established such ideas were. The Scientific Origins of National Socialism by Daniel Gasman focuses specifically on Haeckel. In spite of their different approaches and emphases, both authors make the point that some of Hitler’s ideas sound as if they had been taken verbatim from Haeckel.

The False God of Nationalism

The reliance on human wisdom alone did not only lead to new approaches to “the Jew” and to ethics; it also led, in the German context, to a new concept of the nation. If we do not hold to Christianity, from where do we derive our sense of belonging, of significance, of eternity? Johann Gottlieb Fichte found it in the nation.

It was perhaps inevitable that with the loss of God, the nation should come to be seen as a substitute. Large enough and important enough to appeal to our need for a higher cause, yet real enough to be grasped by the natural mind, the welfare and advancement of the nation was seen more and more as the highest aim and ideal. Fichte is a striking example of this.

In his Addresses to the German Nation, Fichte (writing in the Napoleonic era) saw the nation as “the manifestation of divinity.” The development of the national character was “the highest law in the spiritual world,” “the rule of law and divine order.” The vague “Absolute” or higher spiritual force of German idealist philosophy worked through national groups to achieve the advancement of mankind—and the purest race, the one most in harmony with that higher reality, was the German race.

Destined to lead mankind on its ascent to moral perfection, it was the German People, the Volk, that provided individual Germans with hope, meaning, purpose, and even eternal life. The individual dies, but the Fatherland lives. We need a sense of permanence, and “this permanence is promised to the individual by the continuous and independent existence of his nation” (Addresses). Hitler, too, said, “What is life? Life is the Nation. The individual must die anyway. Beyond the life of the individual is the Nation.” Some of Fichte’s writings survive from Hitler’s personal library, heavily lined in places with his distinctive markings. This way of thinking did not come from the Christian heritage.

Fichte believed that the Germanic peoples of Europe should be united, that arbitrary boundaries dividing the German people should be removed. Hitler’s goal of bringing all Germans “home to the Reich” was not a personal eccentricity but a common theme of nineteenth-century German nationalists. Fichte also felt that the Volk should be purified of unhealthy alien influences. Germany needed to preserve its unique virtues unmixed so that it could continue its mission of “pointing the way to the regeneration of the human race.” This desire for cultural and ethnic purity entailed a deep hatred of Jews as aliens corrupting and contaminating the Volk from within (unlike the French, who contaminated it from without). This concept of cultural pollution was later combined with the concept of racial pollution.

Fichte’s Contribution to the Correct Understanding of the French Revolution (1793) is outspoken in its hostility to Jews—and his reasoning is not primarily that of traditional religious anti-Semitism. Jewish greed, selfishness, materialism, alienation from the lofty spirit of the German people, and hostility to the noble and pure German character—to these Kantian themes he added a nationalistic virulence unknown to the more genuinely cosmopolitan Kant.

It was in reference to such ideas that the nineteenth-century Jewish poet Heinrich Heine uttered his oft-quoted prophecy about the collapse of Christianity before a revived paganism, the “brutal Germanic lust for battle” that Christianity had only tamed but not eliminated. When Heine spoke of a revived Thor smashing the Gothic cathedrals with his giant hammer, he was referring specifically to the repudiation of traditional values he saw in “Kantian criticism, Fichtean transcendental idealism, and even Naturphilosophie” (which stressed union with fundamental powers of nature rather than submission to divine law). Heine’s work On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany shows a much profounder insight into the origins of National Socialism than do most writers who have the advantage of hindsight.

The widening abandonment of traditional Christianity as the nineteenth century progressed left a spiritual void, a deepening moral and cultural vacuum. Nationalism began increasingly to emerge in Germany as a substitute—and from exaltation of the nation, it is a short and simple step to exaltation of the leader of the nation in a manner totally inconceivable in a Christian context.

Into the Void

Racism, militarism, imperialism, euthanasia, political authoritarianism, and new themes of anti-Semitism—such were the fruits of men who rejected the Bible and relied solely on their own intelligence. All of this being so, we can only speculate about the motives of historian Richard Evans, who, in his book The Coming of the Third Reich, tries to link the Nazi policy of euthanasia to “Protestant charities” whose “doctrines of predestination and original sin” led them to embrace Nazi practices, including forced sterilization—as if euthanasia or any other such modern innovations had ever been practiced or even heard of in Luther’s Saxony, Calvin’s Geneva, or Knox’s Scotland. In another book, The Third Reich in Power, Evans clearly recognizes Hitler’s faith in science and its vision of “a world ruled by ineluctable laws of Darwinian competition between races and between individuals,” which was “the sole criterion of morality.”

People viewed essentially as animals locked in a pitiless and amoral struggle; traditional ethics derived from Christianity dismissed as useless fictions; the loss of individual identity leading to membership in the national group as the source of identity and self-worth; the dying of the weak and the sick seen as a natural and healthy means of weeding out the unfit; Aryan supremacy; belief in a scientifically and rationally ordered community; Jews as a threat to a mythical racial purity, plotting to control the world—these and other modern secular ideas combined with various historical and social factors to make the Holocaust not inevitable, but possible.

These ideas did not emerge from Christianity. They emerged from the rejection of Christianity, and they flourished in the intellectual and spiritual void created by modernism. Why shouldn’t we use the hair and skin of dead people, if they are nothing but animals? Why not leave the sick, the weak, and the inferior to perish miserably, if that is just the way things are?

Much more could be said about other German thinkers, especially Richard Wagner and H. S. Chamberlain, whose views were in many ways close to or even identical with Hitler’s. More could be said about such things as the masterful use of modern bureaucracy and technology to achieve detestable ends—but those ends were conceived in the realms of thought, thought based on the wisdom of the world, and on the repudiation of the Christian religion. As Christ said, “If the light that is in thee be darkness, how great is that darkness!”

Joe Keysor has been teaching English overseas since 1995—in China, Oman, and now at Prince Sultan University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He has written two books on the subject of Hitler and Christianity (both published by Athanatos Christian Ministries): A Horror of Great Darkness: Hitler and the Third Reich in the Light of Biblical Teaching (2014) and Hitler, the Holocaust and the Bible: A Scriptural Analysis of Anti-Semitism, National Socialism, and the Churches in Nazi Germany (2010).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor