View

What Is Man?

Anthony Esolen on What Raskolnikov Knew & Translators Have Lost

In an otherwise splendid work, the Catholics recently charged with translating the Mass from Latin into English dropped a word of tremendous mystery. On Ash Wednesday, when the priest marks the foreheads of the faithful with ashes, he says, echoing the words of God to Adam after the Fall, “Remember, man, that thou art dust, and unto dust thou shalt return.” At least, that is what the priest said when I was a boy. But in the meantime, the word man, in its inclusive sense, has come to be regarded as offensive to women. So the new translators blinked. The crucial word homo in the Latin has been translated as—null. “Remember that you are dust,” the priest will say, “and to dust you shall return.”

The loss is heavy. Before I discuss the meaning of the word, I should like to recall a scene in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment. It is, I believe, the climax of that tremendous work. The young girl Sonia, in love with the hero Raskolnikov, urges him to confess the murder he has committed. She—who has known sin and suffering and degradation in her own life—says that he must go out into the public square, in broad daylight, and throw himself to the ground, crying out that he, he alone, has sinned against all mankind and the whole earth, and that he alone is responsible for all the wickedness that has ever been done. Raskolnikov does exactly that. “Plastered,” says a bystander.

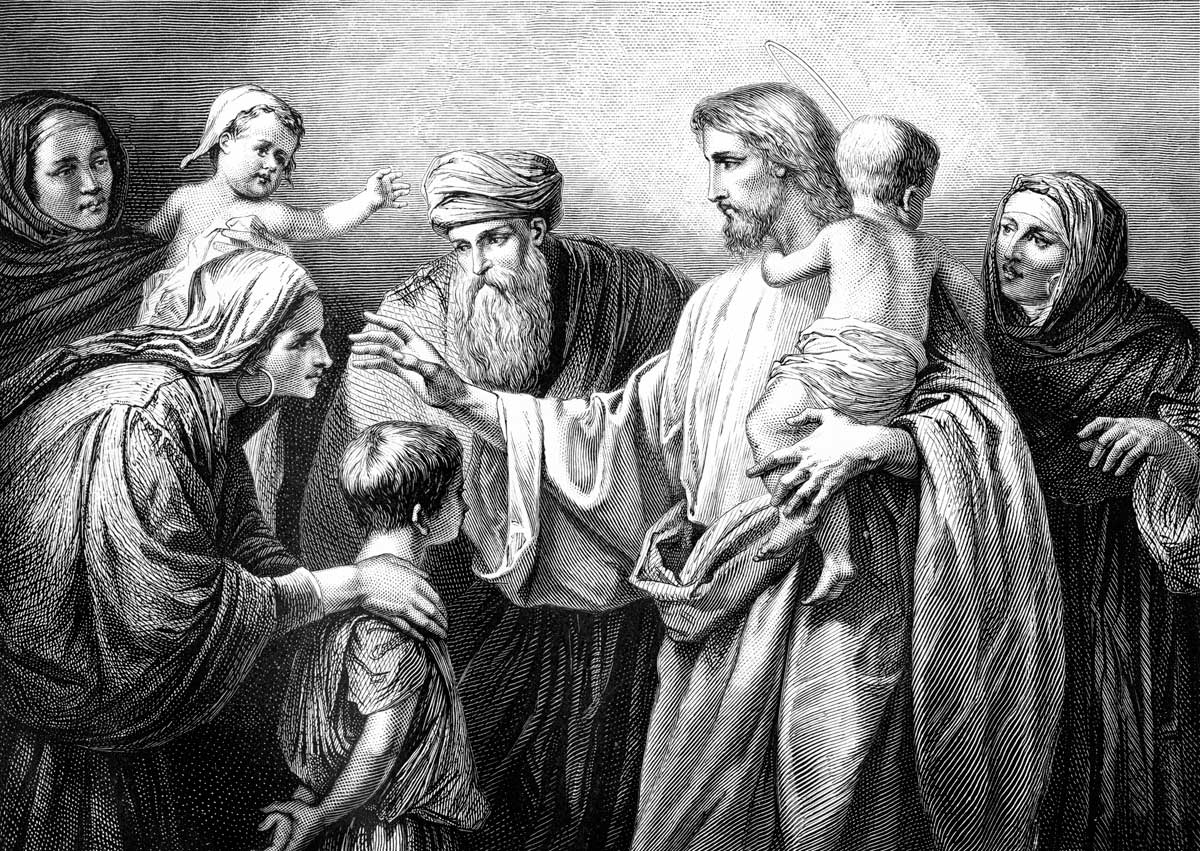

“How can such penance make sense,” we ask, “when each man is responsible only for his own sins?” But in a mystery that we can hardly begin to grasp, we have all been involved in the sin of Adam and Eve, and therefore in the sins of one another. We must not think of Original Sin as simply a thing that happened long ago, as if our own names were not also Adam and Eve. Yes, Adam is the root, and we perhaps are the stalk or the flower, but the plant is the same. That is why we need to be grafted upon a new root; we need to be branches of a new vine. Says St. Paul: “For as by the disobedience of one man, many were made sinners; so also by the obedience of one, many shall be made just” (Rom. 5:19). My sins are not only mine, but the sins of man, and the sins of man are mine.

No Substitute for Man

It is fascinating to consider, then, how the mystery of our involvement in the sins of one another, and then the mystery of our communion in Christ our Redeemer, is intimated by the very word man. For it is not clear, on logical grounds alone, why there should even be such a usage of the word. We do not speak of The Ascent of Dog, or The Meaning of Horse, or The Glory and Shame of Bee. “The proper study of Mankind is Man,” writes Alexander Pope, using that powerful singular term, man, for the being whom he calls “the glory, jest, and riddle of the world.” I am not only a man; I am man, fallen man, man longing for the divine, man in dire need of grace, man wandering in the valley of the shadow of death, man dwelling in time and oriented towards eternity. Homo sum, says the character in Terence; nihil humanum alienum mihi puto—I am a man—or I am man; I consider nothing of man as foreign to me.

That very being-for-one-another, even being-in-one-another, is to be found in the universal, singular, personal sense of man. Every language I know of has such a word: Hebrew adam, Greek anthropos, Latin homo, French homme, Spanish hombre, Italian uomo, German Mensch, Anglo Saxon wer, English man. Sometimes the word is of masculine gender, and means human being irrespective of sex (Hebrew, classical Latin). Sometimes the word’s secondary signification is “adult male,” but with the masculinity not emphasized (later Latin, New Testament Greek). Sometimes the word derives from an older masculine word (German, Anglo Saxon). Sometimes the word’s primary signification is adult male, while its secondary signification is human being irrespective of sex (English, the Romance languages). But each of these languages has a word that names man, the universal, including everyone in one being, and therefore also naming each: a universal, singular, and personal term.

A little consideration shows that there is no substitute in English for man. None of the alternatives do the necessary work. Human being is singular and somewhat personal, but it is not a universal term; we do not conceive of the fall of human being. Humanity is abstract and impersonal, and names a quality rather than a being. People is plural, and not necessarily universal; I am not people, and the sin of people might mean the sin of John and Mary and Agnes and Bill, but not the sin of all people considered as one. Mankind is a universal, but not personal. The priest could never say, “Remember, mankind, that thou art dust,” because he would then seem to be speaking not to the penitent, but to a vast generality. Men and women is not universal—it excludes children!—and introduces an irrelevant distinction of sex. Person is singular but not universal, and is in any case not limited to man; angels, too, have personal being, as do the Persons of the Holy Trinity.

The people who revile this use of man, then, would have us eliminate the very thought which the word signifies. But that is unreasonable. It is as if one were to say, “We shall not use the word tree.” What substitute is there? Why should we not have a word for a thing that is in our common experience? Similarly, why should we not have a word that corresponds to our mysterious sense that each one of us carries the burden of all, and that the good of all is oriented towards the good of each?

The Good of Man

In The Person and the Common Good, Jacques Maritain reminds us of these complementary modes of man’s being. We are weak creatures. We cannot provide, by ourselves, for our most basic needs, not to mention the fulfillment of our beings. We are therefore necessarily social, and must yield to the common good: “By reason of its deficiencies—evidences of its condition as an individual in the species—the human person is present as part of a whole which is greater and better than its parts, and of which the common good is worth more than the good of each part.”

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor