Feature

The Way of St. James

My 500-Mile Pilgrimage on El Camino de Santiago

Few Americans have heard of the Camino de Santiago, the Way of Saint James, and I have been asked how I found out about it (although perhaps it would be more accurate to say the Camino found me—a common experience). I like to hike, and I especially like to hike from inn to inn over a long distance. It is almost impossible to do that in North America—the towns are too far apart. I also like to hike where I can see a variety of things—scenery, churches, museums—again, difficult in North America.

One website advertised tours of the Camino de Santiago in Spain. I was intrigued, and started reading about it. The more I read, the more interested I became. Two books especially clinched it for me. One, To the Field of Stars, was by a priest, Kevin Codd, who was once the rector of the small American seminary in Louvain, Belgium. The seminary had problems—mostly declining enrollment—and he needed to think and pray, so he decided to walk the principal stretch of the Camino, from the town of St. Jean Pied-de-Port at the foot of the Pyrenees Mountains to Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain. As a priest, he was attuned to the symbols and traditions of the Camino.

The other book was from a different perspective: I’m Off Then: Losing and Finding Myself on the Camino de Santiago, by Hans Peter (Hape) Kerkeling, a gay German comedian. He was a couch potato, but one day the idea entered his head: “I am going to walk the Camino.” So he did. He kept a diary, which he later talked about on a TV show. A publisher heard him, and asked him to write it up into a book, which became a bestseller, and the Camino is now full of Germans, one of whom wrote on an underpass, Sankt Hape, bitte für uns (St. Hape, pray for us). John Brierley’s guidebook, A Pilgrim’s Guide to the Camino de Santiago gives good advice about practical matters and the right attitude.

As I have passed my sixtieth year, I was concerned about whether I could walk 500 miles, the distance from St. Jean to Santiago. Most pilgrims do shorter sections over the years and combine them, but I decided I had best walk the whole 500 miles at one go, since “at my back, I always hear / time’s winged chariot hurrying near.” I read the blog of a 70-year-old retired teacher who completed the Camino, so I decided I could do it.

Most pilgrims carry all their possessions in a backpack, and show up each day at a new refugio, a dormitory run by a church or village or private association. I decided that I was a little too old for a dormitory, and my doctor had warned me that my days of hiking with a full backpack were over. I discovered a service called Follow the Camino, which would make reservations at small hotels at 12- to 20-mile intervals and transport my duffel bag between hotels. This allowed me to take just a daypack. I decided to walk in the fall, to avoid the blistering heat of Spain in the summer. In July 2010, I spent three weeks hiking in Glacier National Park and Yellowstone to get into shape.

Becoming a Pilgrim

On September 14, 2010, the feast of the Triumph of the Holy Cross, I went to Mass, and a friend, Father Rose, blessed me and presented me with my pack (mochila), hiking pole (bastón), and a leather strap with a scallop shell (venera), on which my wife had painted the cross of Santiago. He gave me the Pilgrim’s blessing:

In the name of the Lord Jesus Christ, shoulder this backpack, which will help you during your pilgrimage. May the fatigue of carrying it be expiation for your sins, so that when you have been forgiven you may reach the shrine of St. James full of courage, and when your pilgrimage is over, return home full of joy.

Receive this staff as support for the journey, so that you are able to arrive safely at Saint James’s feet.

Receive this shell as a sign of your pilgrimage. With God’s grace, may you behave as a true pilgrim throughout your entire journey.

O God, you who took up your servant Abraham from the city of Ur of the Chaldeans, watching over him in all his wanderings, you who were the guide of the Hebrew people in the desert, we ask that you deign to take care of this your servant, who, for love of your name, makes a pilgrimage to Compostela.

Be a companion for him along the path,

a guide at crossroads,

strength in his weariness,

defence before dangers,

shelter on the way,

shade against the heat,

light in the darkness,

a comforter in his discouragement,

and firmness in his intention,

in order that, through your guidance, he might arrive unscathed at the end of his journey and, enriched with graces and virtues, he might return safely to his home, filled with salutary and lasting joy.May the Lord always guide your steps and be your inseparable companion throughout your journey.

May the Virgin Mary grant you her maternal protection, defend you in all dangers of soul and body, and may you arrive safely at the end of your pilgrimage under her mantle.

May St. Raphael the Archangel accompany you throughout your journey as he accompanied Tobias, and ward off every contrary or troublesome incident.

Go in the peace of Christ.

The next day I was off to Paris, where I stayed a few days to get over my jet lag, to visit the Musée de Cluny, and to wait for my luggage to catch up with me (I know the ways of airlines). The hiking poles had disappeared in the hold of the plane, and the airline couldn’t find them. Where was I going to find hiking poles in Paris? I was staying on the left bank, near the Sorbonne, and strolling around I discovered a dozen outdoor stores near my hotel. I found excellent poles (better than the ones I had had); it was my first lesson in the truth of the saying, “The Camino provides.”

I took the train to Bayonne, where I changed to a two-car local train full of pilgrims and their backpacks, which took us up a mountain valley to St. Jean Pied-de-Port, the last town in France. There I had my pilgrim’s passport stamped and got a lecture about how difficult the first day was. In the morning I started climbing the mountain, and it wasn’t hard compared to trails in the Rockies—mostly paved or dirt farm roads, and no precipices.

I walked across into Spain and to Roncesvalles, where Roland fought and fell. The abbey church, like most churches on the Camino, is a severe Romanesque structure. I went to the pilgrim’s Mass on the feast of St. Matthew. Five priests in red vestments chanted vespers in Spanish before the Mass. The celebrant gave the pilgrim’s blessing in all the languages of the pilgrims in the congregation—including Japanese, for which he used not the Western but the Japanese gestures of benediction. Then all the lights of the church were turned off except for the ones shining on the Virgin and Child under the baldachino. We sang the Salve Regina in Latin, and my first day had ended. I was a pilgrim.

The Story of the Camino

What is a pilgrim? What is a pilgrimage? Going to a sacred place is an act of natural religion. We all sense that our life is a journey from the mysterious darkness from which we have all come into the mysterious darkness into which we are all going. We also sense that, in some places, the veil between this visible world and the invisible world is thinner than it is elsewhere. And so, through the ages, people have walked to those sacred places. In Celtic and in Roman times, people walked the Camino to Finisterre, the end of the world, to see where the sun disappeared into the Atlantic, as we will all disappear, and they hoped that the rebirth of the sun every morning was a sign that we, too, would somehow be reborn, that death was not the end.

Jews went up to Jerusalem to see the Temple, in which the Glory of the Lord dwelt. Christians went to the Holy Land to see the places where the world was redeemed by the life and death of Jesus. Others went to Rome to visit the tombs of the martyrs Peter and Paul. And starting in the ninth century, pilgrims started going to Compostela.

A legend explained that Anne, the mother of Mary, had been widowed twice and married three times. By her first husband, she was the mother of Mary and the grandmother of Jesus; by her second marriage, she was the grandmother of James the Less, and by her third marriage, she was the grandmother of James the Great, the apostle, who was therefore a half-first cousin of Jesus.

Jesus had commanded his apostles to go to the ends of the earth, so James went to Spain and preached in Galicia, the rainy corner in the northwest, facing the Atlantic. Later, he returned to Jerusalem, became its bishop, and was killed by Herod—the first apostle to be martyred. His followers put his body in a boat, which they then put adrift on the sea. It came ashore in Galicia, and his body was taken and interred in what is now Santiago de Compostela. (There is in fact a first-century Roman cemetery there). The memory of his tomb was lost.

But then, in the ninth century, a Galician shepherd looked up and saw, above a certain field, stars dancing in the sky (a meteor shower?). He told his bishop, who investigated the site and found the tomb of St. James, Santiago, where he built a church. Pilgrims started coming, and churches and refuges were built all along the route to accommodate those who were coming to the campus stellae, the field of stars.

They came, and came, and came: 500,000 pilgrims a year at its height, in the Middle Ages; tens of millions over the centuries, from all over Europe. The Reformation rejected pilgrimages as vain works, and so the Camino then began to falter, and it finally died out in the nineteenth century.

But the Spanish revived it in the 1960s; in the first year, about 300 people received their Compostela, a certificate testifying that they either walked the last 100 or biked the last 200 kilometers. In 2010, a holy year because the feast of St. James fell on a Sunday, over 270,000 pilgrims received the Compostela.

Signs & Memorials

And here I was, walking the same path. My German ancestors came from Regensburg, which is on a branch of the Camino, (Jacobsweg in German), and almost certainly some of them had come this way, walking on the same stones I was walking on, praying for their family, their descendents, for me.

I saw the line of pilgrims on the road in front of me and behind me, and, like everyone else, I sensed I was part of something far greater than I was, something that extended in space and in time, to the ends of the earth, back through the centuries even before James preached, and forward—until when? Perhaps until Christ comes in glory.

The Camino is marked by several signs: mostly by the scallop shell, the venera—because pilgrims would pick them up on the Galician coast and wear them as a badge to show that they had been to Compostela—and by the yellow arrow, la flecha amarilla, which a priest in modern times popularized as a waymark for the Camino. So I followed the shells and arrows through Navarre.

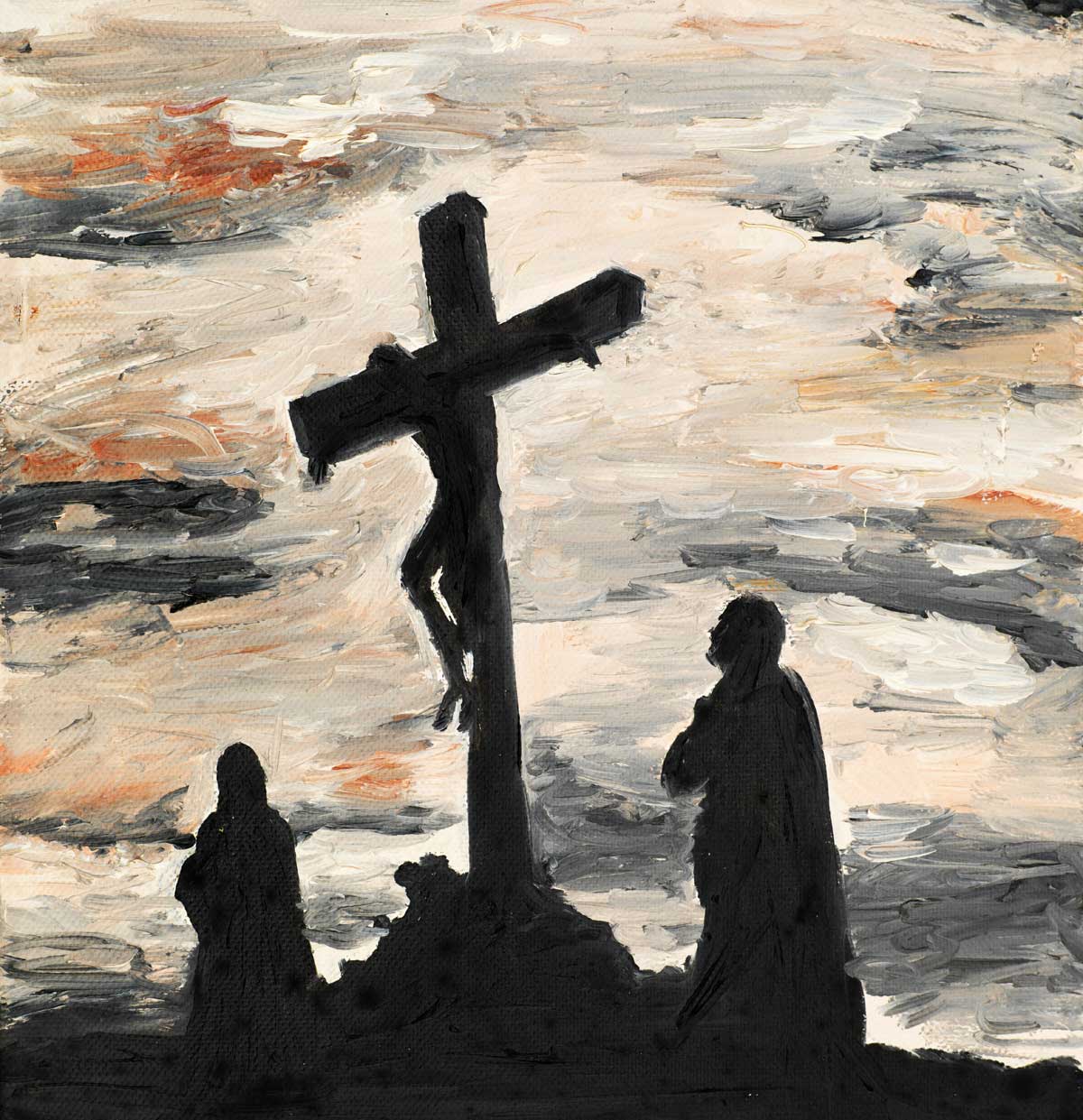

I came to a sign indicating a detour off the Camino to a Romanesque church. It was only a few hundred meters away, so I decided to see it. It turned out to be a few hundred meters up a rocky, barren hill, which I had to scramble up. I entered the church and prayed. As I was leaving, I saw a life-size crucifix on a side wall, placed so that pilgrims could kiss the bleeding feet of Jesus—because by this time most pilgrims knew what it was to have bleeding feet. Someone had found pads of post-it notes shaped like yellow arrows and left them for pilgrims to write their petitions on. Around the crucifix were hundreds of arrows pointing to Jesus with prayers in all languages: “For my dying child”; “For my dead husband”; “For strength to walk the Camino”; “Please heal my wife.” I wrote my petition, “Por mis niños” (“For my children”) and added it, and kissed the feet of Jesus.

My feet were doing quite well. Ecco boots have been my favorite for thirty years, and they and foot cream spared me blisters. I was surprised that the Camino was not grueling. It was hard because it went on day after day after day, but the paths were almost always easy—farm roads, dirt or graveled, and only rare stretches on the shoulders of highways. The robbers have disappeared, and the resurgent Spanish wolf (2,500 in northern Spain) seems to have found something other than pilgrim to dine on, so the main hazard was Spanish drivers. I did not have any close calls, but there were memorials along the way to pilgrims who had died on the Camino—some from natural causes, but one memorial was to a group of pilgrims who had been killed at the same time—I suspected by a car or truck. The Camino is safe, but, I thought, there are worse ways to die than walking to the tomb of an apostle.

I began noticing disturbing reminders of recent history. One church had a cloister paved with dozens of memorial stones—they were all for young men who had died in 1936, in the first months of the Spanish civil war. Village churches had plaques—to their pastors, killed in 1936 or 1937. In the Cathedral in Léon a plaque memorialized the archbishop of Léon and the 37 priests who had been murdered by the Republicans during the civil war.

But the Republicans also had their memorials. In a forest, I came upon a recent pillar, put up by the descendents of the villagers whom Franco’s forces had brought there and machine-gunned because they were suspected of socialist sympathies. Until Franco died, the murdered men could not be mentioned, but now there were fresh flowers where their blood had flowed.

All along the Camino are carved crosses, some medieval, some modern, But I found the informal memorials to be more moving. For a mile or so, the Camino runs along the expressway, and a chain-link fence separates the path and the roadway. On this fence pilgrims have woven tens of thousands of crosses of sticks and twigs and bark. I added mine. In forest roads pilgrims had gathered and arranged stones in the shape of a heart, crowned by a cross enclosing the words Paz and Amor, peace and love. At the beginning of the Camino in France there is a large stone cross with the words Je suis le Chemin. But in Spain people had written in yellow paint on their houses: Yo soy el Camino.

The Pull of the Camino

Yo soy el Camino—I am the Way. Jesus is the way to the Father, but is Jesus ever left behind, or is he forever the Way? Will we always be on that way, always pilgrims, always entering deeper and deeper into God, but always through and with Jesus, never leaving him, the Incarnate Son, and his Body, the Church, behind? A church on the Camino has this meditation: “When you reach Santiago, you have not reached the end of your pilgrimage. You have reached only the beginning of the last stage of your pilgrimage. Your earthly pilgrimage will end when you meet Jesus.” But then the heavenly pilgrimage starts.

The pastor of San Juan de Ortega, near Burgos, has this meditation for pilgrims:

If you have to die tomorrow, on the Camino, tell yourself that your life is completely fulfilled because you will be in a state of absolute search. And if you return home, tell yourself that you are still on the way, and that you will always be on the way, because it is a way that knows no end.

A hymn goes, “Thou art the Way; / To thee alone / From sin and death we flee.” But we do not only flee. We are pulled. On a concrete-block fence around a factory near Nájera is a poem in German and Spanish:

Dust, mud, sun and rain,

Is pilgrims’ road to Santiago.

Thousands of pilgrims

And more than a thousand of years.Pilgrim, who is calling you?

What hidden force is attracting you?

It’s not the field of the stars

Or the grand cathedrals.It’s not the bravery of Navarra

Or the wine of Rioja,

Neither the Galician seafood

Nor the fields of Castile.Pilgrim, who is calling you?

What hidden force is attracting you?

It’s not the people on the Camino

Or the rural customs.It’s not the history and culture

Or the cock in Calzada,

Neither the Gaudí palace,

Nor the castle of Ponferrada.I see them all when passing by,

It is a joy to see it all.

But the voice that is calling me

I feel much deeper.The power that’s pulling me,

The force that’s attracting me,

I can’t explain.

Only he above knows it.

The pull—the pull; everyone feels it. I did the Camino in stages; every six days or so, I stopped for two nights to rest and to do my laundry, but I found myself begrudging the pause. Yes, the Spanish towns were beautiful and interesting, but at the end was Santiago, and I felt like iron drawn by a magnet, day after day, along the road, up the mountains, through the rain, to the end.

Walking in Prayer

I walked and walked and walked, from six to ten hours a day. I decided to follow Father Codd’s practice of saying the rosary in the morning: “Our Father, who art in heaven . . . Hail Mary, full of grace . . . Glory be to the Father . . . O my Jesus, save us from the fires of hell; lead all souls to heaven.” Then for an hour or two I said the Jesus prayer in time to my poles: “Lord Jesus Christ (click), Son of God (click), have mercy on me (click), a sinner (click).” A pilgrim doesn’t just pray when he walks; his walking becomes a prayer—his body prays as it moves and breathes—and suffers.

I asked God what he wanted me to do with my time. I decided to review my life, to thank God for everyone I had known, and to pray for each one. My parents, my family, my childhood playmates, my neighbors, my teachers, my fellow students, my co-workers, people I had had run-ins with (a full day for those), people who are sick, people who had died, a day to each member of my family, thinking of all the good things about them, praying that we would one day be with the Lord forever. That took most of the day.

In the afternoons I was tired and achy; I had brought my iPod and tried music. The best was Celtic harp, soothing but not overwhelming. Part of the Camino is meadows, with sheep and cows and byres and barns and cribs. As I walked through these pastures, I heard a melody on the harp and remembered the words:

The King of love my shepherd is,

Whose goodness faileth never;

I nothing lack if I am his

And he is mine forever.Where streams of living water flow,

My ransomed soul he leadeth

And, where the verdant pastures grow,

With food celestial feedeth.Perverse and foolish oft I strayed,

But yet in love he sought me

And on his shoulder gently laid

And home rejoicing brought me.In death’s dark vale I fear no ill

With thee, dear Lord, beside me,

Thy rod and staff my comfort still,

Thy cross before to guide me.And so through all the length of days

Thy goodness faileth never.

Good Shepherd, may I sing thy praise

Within thy house forever.

I thought of my sins, my perversity, and my folly—a subject for long meditation.

The Camino Provides

A pilgrimage is a living parable of the Christian life. I frequently felt that I was living a Bergman film; everything seemed to have significance: the line of pilgrims walking up a red dirt road on a hill into the blue sky, the wood crosses outlined against the sky, the flocks of sheep led by shepherds and burros, the just-harvested wheat fields, the vineyards ripening in the autumn sun, my shadow with its backpack and poles stretching along the road.

I overheard snatches of conversation: “They say that the pilgrimage doesn’t begin until you return home”; “The important thing is not to get there first, but to get there together”; “The Camino provides.”

The Camino provides. The food was tolerable, but I had problems with Spanish hours. Lunch at 2:00, dinner at 9:00—it was hard when you started hiking at 6:00 a.m. I tried to buy lunch at a store and take it with me, but I had to do it every day, and stores weren’t always open. And all that Spaniards have for breakfast is a roll and coffee with milk (the warming but not sustaining café con leche).

After walking for several hours one morning on a mostly empty stomach, I entered a town hoping for something to eat. I passed a small market, but it was darkened at 9:00 a.m., and I thought bad thoughts about Spanish business practices. I was unsuccessful in my search, but as I left the town, I walked past the darkened store again and noticed people in it—it was open, but they didn’t turn on the lights because electricity is expensive. I went in, and a cheerful sales clerk recommended a wonderful goat cheese, found fresh rolls, and then picked out the ripest peach for me. I left feeling a little ashamed; how had I forgotten that the Camino provides?

And so on, in prayer and quiet and music day after day, for forty days: Pamplona, Burgos, Léon, Astorga, and dozens of small poblaciones and villages and towns passed by. I would leave at first light, and as the sky reddened behind me, I would look back at the rooftops and church towers of the town outlined against the dawn. Then onward, step after step, a million steps to Compostela (500 miles x 1,000 paces per mile x 2 steps per pace).

The Last Day

I called home every day, to report that I had made it to the hotel. I had cards in my daypack and a wallet with my emergency contact information in the U.S., but I knew that my wife would feel better if she heard from me. She would be flying to Compostela a few days before I arrived and staying at the Parador on the cathedral square, originally a hospital for pilgrims built in 1492 by Ferdinand and Isabella. I told her I would be arriving in the afternoon, but if it was raining not to wait in the square, but in the Parador.

The last day it rained on and off; it was raining heavily when I entered Santiago—so heavily that I lost track of the yellow arrows and wandered down the wrong avenue. A helpful Spaniard put me on the right track. The Spanish were amazing. I was the 250,000th person that year to tromp through their towns, but at each one, someone would always greet me with a cheery Buen Camino.

I entered the old city through the medieval gate and walked the narrow street, following the flow of pilgrims with their ponchos and poles and backpacks. Five hundred miles, and I was arriving. Galicia is Celtic, and its instrument is not the guitar but the bagpipe, the gaita. The Camino as it enters the cathedral square goes through an arch, where a gaitero is always piping away. I heard him through the rain. I didn’t know what, if anything, I would feel as I finished—I didn’t want to be disappointed by expecting a great high and getting nothing.

I entered the cathedral square while it drizzled. I looked up to the baroque façade of the cathedral and saw Santiago Peregrino, St. James the Pilgrim, there, welcoming us—but he had been with us all along, whether we knew it or not. As I stood gazing at him, groups of youthful pilgrims entered the square and broke into song in a dozen languages. Pilgrims would spot fellow pilgrims they had met somewhere along the Camino and embrace them: “Amigo, Peregrino! You made it—how wonderful.” I had made it, as a thousand people a day had done even on October 31.

I am usually not interested in other people’s “religious experiences,” nor do I expect them to be interested in mine. But when many people have had the same type of experience in the same circumstances, the matter becomes more interesting. Something objective is happening, perhaps because of a common human nature, perhaps because of an external reality, or a combination of both. I felt as many pilgrims feel: just one more step and I would be through the veil, into heaven, which was drawing close around me.

I entered the Parador, and asked the receptionist to call my wife in her room. She wasn’t in, but as I turned toward the salon, she spotted me, my hat and poncho dripping wet, and she ran across the room. We embraced, and all eyes (she told me) were on us. Journeys end in lovers’ meeting.

The Call of the Lord

The next day I presented my passport, which had been stamped all along the way, and received my certificate, my Compostela, testifying that I had completed the Camino to honor St. James. I then entered the cathedral. Above the main altar is a life-size statue of Santiago, and behind the altar are stairs to climb to give Santiago an abrazo and to tell him one’s dearest prayer. I hugged him and asked him: “Santiago, please welcome me and my family into Paradise.” I then went to the chamber under the main altar that houses the reliquary that contains his bones. I knelt on the stone floor with other pilgrims, and we prayed, close to one who had walked with Jesus on earth, who had known him as a child, who had gone to the ends of the earth to tell people that Jesus was Lord and had risen from the dead.

That day, the feast of All Saints, Todos los Santos, we went to the pilgrim Mass. We arrived at 11:00 a.m. for the noon Mass, and the pews were already full. The cathedral continued to fill up. Parents brought numerous children, some of whom sat on the bases of the pillars and played cards while waiting for Mass to start. (There is a statue in a Camino church of St. Anthony playing cards with the child Jesus.) Then the Mass began. Men in velvet robes played krumhorns and trumpets in the procession that carried the image of Santiago around the aisles.

Music has always been important on the Camino. The elders of the apocalypse on the tympana of Camino churches are shown playing musical instruments (including the Galician bagpipe). The boys’ choir in the cathedral began singing like angels, and eight men started the botafumeiro, the world’s biggest censer, about six feet across. They set it swinging on a hundred-foot chain. It swooped up to the ceiling over our heads, emitting flames and billows of smoke. Pilgrims who had timed themselves to arrive at noon began circulating through the church in their hiking clothes. The cathedral was full and overfull and still people entered, and they were welcome. It was a foretaste of the liturgy with all the saints that will go on forever.

Albert-Marie Besnard said of the pilgrim:

The day when the Lord calls him, he will be neither disturbed nor surprised. He will have known this departure, he will have loved it—this manner of going and leaving all things, ready to take them up again or never again to find them, as God wills. Renunciation will be familiar to him, he has rehearsed it and drilled it, he is ready. For one day, having taken the pilgrimage seriously, he finds death sweet and promising, and this fatherland which he has searched for on earth in parable, he is ready at last to find in eternity.

Charles Péguy has Jesus say:

Je vous attends. Je ne suis pas loin, juste de l’autre côté du chemin. Vous voyez, tout est bien. “I am waiting for you. I am not far, just on the other side of the road. You will see, all is well.”

Vraiment, tout est bien. Vengo, Señor Jesús. •

Leon J. Podles holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Virginia, has worked as a teacher and a federal investigator, and is president of the Crossland Foundation. He is the author of The Church Impotent (Spence), Sacrilege (Crossland Press), and Losing the Good Portion: Why Men Are Alienated from Christianity (St. Augustine Press). Dr. Podles and his wife have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor