Column: Contours of Culture

Leisure Suits Us

On Josef Pieper's Leisure, the Basis of Culture

by Ken Myers

At present count, there are 255 books in my library with the word “culture” in the title. The shortest title is Culture, by sociologist Chris Jenks. The longest is Richard Olson’s Science Deified and Science Defied: The Historical Significance of Science in Western Culture, from the Bronze Age to the Beginnings of the Modern Era, ca. 3500 b.c. to ca. a.d. 1640. There are books about Consumer Culture, Convenience Culture, and Corporate Culture. There are several studies of Youth Culture and only one of Grown-Up Culture. There are reflections on the Culture of Technology, the Culture of Displacement, the Culture of Criticism, the Culture of Complaint, the Culture of Cynicism, the Culture of Narcissism, and the Culture of Celebrity (all of which may actually be in the same realm).

Other titles reference Doubting Culture, Therapeutic Culture, Extroverted Culture, Decadent Culture, and Divorce Culture. A book about Amish Culture sits not far from a volume on Rapid-Fire Culture. I didn’t count all the books with the variant “cultural” in the title, but the breadth and variety continues on that list as well.

In compiling this list, I saw a number of titles beckoning me to read them for the first time, a few that I’ve read repeatedly, and some that have profoundly shaped my thinking and writing about culture. Terry Eagleton’s The Idea of Culture does a good job at explaining why the word “culture” is one of the most complicated in the English language (second only to “nature”). I’ve discussed T. S. Eliot’s Christianity and Culture in this column before; consideration of its arguments should be mandatory for any Christian conversation about culture. So should the reading of Josef Pieper’s slender volume Leisure, the Basis of Culture.

Originally published in 1952, the book contains two essays, each written in the form of a lecture and given in Bonn in 1947: the title essay (the original German title was “Musse und Kult,” “Leisure and Worship”) and another piece called “The Philosophical Act.” The first edition of Leisure, the Basis of Culture featured an introduction by T. S. Eliot, in which the poet lamented a certain sickness in philosophy that Pieper’s work might help cure: “his influence should be in the direction of restoring philosophy to a place of importance for every educated person who thinks. . . . He restores to their position in philosophy what common sense obstinately tells us ought to be found there: insight and wisdom.”

Calm & Attentiveness

Pieper was obviously concerned that postwar Western culture was becoming preoccupied with work, guided by a very dehumanizing understanding of the place of work in human life. Communist countries were allegedly workers’ paradises, while capitalists (according to Max Weber) lived in order to work. Pieper acknowledged to his 1947 German audience that the devastation of the previous years meant that there was indeed a lot of work to be done. But he reminded them of the insight of Aristotle—taken up within the Christian contemplative tradition—that “we work in order to have leisure.”

But “leisure” in that older framework was not idleness or the killing of time (a revealing metaphor). Pieper reminds us that the Greek word for leisure is skole, from which (through Latin) we get our word “school.” In the classical and premodern Christian understanding, idleness “is the source of many faults, and among others of that deep-seated lack of calm which makes leisure impossible.”

Leisure requires calm because it is marked by attentiveness: “leisure is a receptive attitude of mind, a contemplative attitude, and it is not only the occasion but also the capacity for steeping oneself in the whole of creation.” In Pieper’s view, the purpose of education is not to prepare us for the world of work, but to enable us to be true people of leisure. If life is more than work, then education is far more than vocational or professional training.

A functionary is trained. Training is defined as being concerned with some one side or aspect of man, with regard to some special subjects. Education concerns the whole man; an educated man is a man with a point of view from which he takes in the whole world. Education concerns the whole man, man capax universi, capable of grasping the totality of existing things.

Rooted in Worship

Leisure involves attentiveness to all things, and education enables some understanding of the whole of things. Culture, for Pieper, is similarly comprehensive:

Culture . . . is the quintessence of all the natural goods of the world, of those gifts and qualities which, while belonging to man, lie beyond the immediate sphere of his needs and wants. All that is good in this sense, all man’s gifts and faculties, are not necessarily useful in a practical way; though there is no denying that they belong to a truly human life, not strictly speaking necessary, even though he could not do without them.

The paradox in that last sentence points to Pieper’s Christian confidence that Man does not live by bread alone, that what makes us fully human is rooted in what St. Paul calls the things that are above, on which our minds are to be set and in light of which our lives are to be lived.

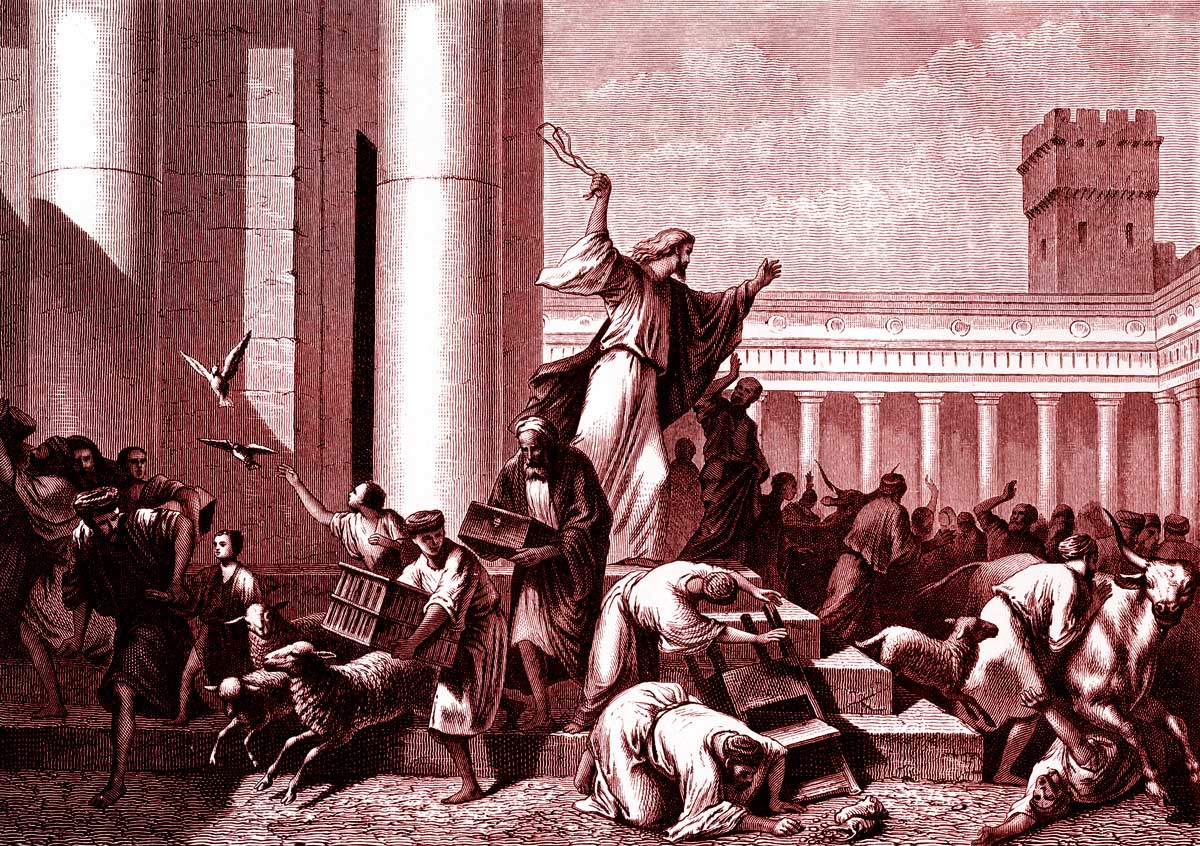

The last section of Pieper’s essay on leisure connects culture with worship. “Cut off from the worship of the divine, leisure becomes laziness and work inhuman.” Holidays are not really experienced except as holy days, just as culture is confused without the cultus of divine worship. Pieper’s remarkable little book suggests that there’s a deep truth in regarding worship as a “leisure activity,” though not in the way that term is now conventionally used. Since liturgy is work, and leisure eschews idleness, the Sabbath rest is surely activating. •

Ken Myers is the host and producer of the Mars Hill Audio Journal. Formerly an arts editor with National Public Radio, he also serves as music director at All Saints Anglican Church in Ivy, Virginia. He is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor