View

Job’s Progress

Peter J. Leithart & Toby Sumpter on Maturity for a Rising Generation

Every generation must wrestle. It is not a question of whether, but of what: What will we wrestle about? Where will we struggle? How will we shed our blood? Sometimes the same struggles continue between generations, while other times the challenges shift with the passing of the guard. Some will face the massive weight of communism; others will set their flank against the encroachments of theological liberalism. One regiment faces the descendents of Pelagianism; another must defend the republic from terrorists.

It is common for a rising generation to tire of the old battles. It is happening today. Many younger Evangelicals today are confused, thinking, “Our fathers wrangled over prayer in public schools, church polity, abortion, worship styles, gay rights, and end-times prophecies. We’ve had enough of that. We’re ready for peace on those fronts. And often, we say we just want peace, period. Do we have to keep fighting? Do we have to keep wrestling? Why all the strife, all the divisions?”

Tired Protestants seek refuge from petty squabbles and increasingly splintered denominations in the perceived fortress of Roman Catholicism or Eastern Orthodoxy. Jaded Evangelicals defect from the Christian Right, and they join ranks with a more ideologically distant candidate, who nevertheless seems alive and hopeful, and exudes a peaceful and calming persona. He’s never served in the military, and for some, that’s to his credit. He’s not a fighter, and thank God for that, they say.

From Priest to Prophet

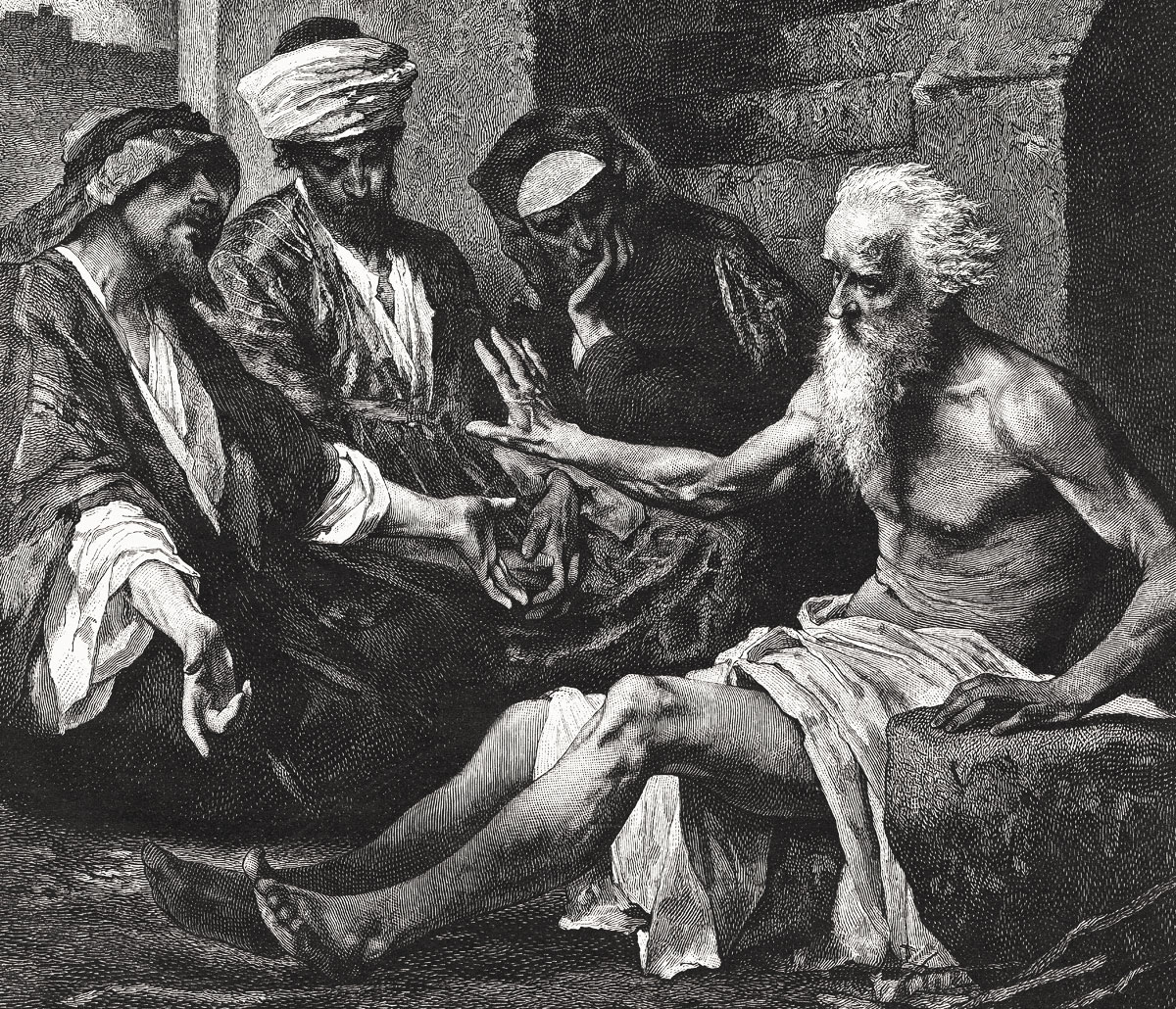

The book of Job issues a serious challenge to those who would avoid conflict. Job has rightly been seen as a biblical locus classicus on the problems of suffering and evil, but the narrative has many other layers. As Rene Girard has suggested in a typically brilliant and infuriating study, Job is a ruler, the three friends are court advisors, and the whole drama is as much a piece of public theology as anything from Aeschylus or Sophocles. To the rising generations who would rather not wrestle, the book of Job argues that they are shrinking back from maturity and ultimately avoiding the way of the Cross, the only way to real peace.

The surface story of wealth–loss–restoration is intersected by another story of progress and maturation. Job begins as a priest who offers sacrifices for his children who may have sinned (Job 1:5). By the end of the story, Job not only offers sacrifices but also prays for his three counselors, and God promises to hear him (42:8). At the beginning, Yahweh is talking with the Accuser, and Job is not among the “sons of God” who appear before Yahweh. By the end, the Accuser is nowhere to be found and Yahweh is speaking with Job. Job has been elevated to one who may speak to God, and he is assured that he will be heard. Job has become like Abraham who intercedes for others (cf. Gen. 20:7).

In becoming like Abraham, Job has become a prophet. Abraham Heschel long ago noted that Israel’s prophets were preeminently members of the divine council, and the story of Job, with its echoes of Genesis, confirms Heschel’s point. According to Genesis, offering prayer is a prophetic privilege (Gen. 20:7), and, like the prophets, Job is identified as the Lord’s “servant” (cf. Jer. 7:25; Ezek. 38:17). Job begins as a priest, but by the end, he has grown to prophetic stature.

Job’s exaltation anticipates Jesus, the greater Servant of the Lord, who learned obedience by what he suffered, who was qualified to intercede before the Father by his incessant debates with hostile opponents, who finally casts the accuser of the brethren from heaven. Job is the story of maturation from priest to prophet, from servant to divine advisor, and the drama shows that the pathway toward maturity is intense debate.

Into the Whirlwind

The question is, How does Job get there? How does he move from “outside” the council of Yahweh to “inside”? He doesn’t get there by rolling over and playing dead. Struck by the mighty hand of Yahweh, Job faces defeat and covers himself in ashes and dust of death. Yet he does not lay down his arms.

He is tempted to. Perhaps his initial response to his wife was a bit too stoic, with shades of pacifism and determinism: “Shall we indeed accept good from God, and shall we not accept adversity?” But Job most certainly does not take what God has given as the last word on the matter. What follows, after a seven-day interlude (Job 2:13), is a plea that comes strikingly close to what his wife suggested. While he does not directly curse God, he begins by cursing the day of his birth, the night he was conceived, and wishing that time could go backward (3:3–8).

The book’s answer is that Job reaches that level of glory and maturity through conflict. The largest part of the Book of Job is an extended dialogue between Job and his three companions, but as we read and listen, we witness a growing storm of words—arguing, debating, and wrestling for the truth. Frequently, the words of the rhetorical combatants are referred to as “wind” (Job 6:26; 8:2; 15:2; 16:3). At the culmination of the story, Yahweh answers “out of the whirlwind” (38:1; 40:6). In other words, the story of Job is a drawing of Job into the whirlwind. The narrative, the argument, the dialogue itself, is Job’s transition into the whirlwind presence of Yahweh.

Job’s Desire

The subject of Job’s speeches is bound up with this very desire. Job, like Orual at the end of C. S. Lewis’s Till We Have Faces, longs to bring his case to God face-to-face. Job’s recurring complaints are that he cannot present his case before Yahweh; he cannot contend with God (9:11). As Job responds to the continued criticisms and accusations of his friends, his repeated desire is to speak with God and receive an answer (12:4; 13:3). Job’s specific hope is that he will be able to “argue my ways before him” (13:15). “Oh that I might find him,” he says elsewhere, for then “I would present my case before him and fill my mouth with arguments” (23:4).

Even Job’s death wish is bound to this desire to have a hearing with the Lord. His plea is to die so that his righteous blood may cry out for justice (16:18). And the full force of his argument finally bursts forth in one of the most famous passages in the book, when he proclaims, “For I know that my Redeemer lives, and he shall stand at last on the earth. And after my skin is destroyed, this I know, that in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself and my eyes shall behold, and not another . . . there is a judgment” (19:25–29).

Job is in the process of searching for wisdom, but he has come to the conclusion that it is not “found in the land of the living” (28:13). “It is hidden from the eyes of all the living” (28:21). Only God has wisdom; only he has searched it out (28:27). This is why Job wants to die: He wants to go before the Almighty and receive an answer; he wants to approach him like a “prince” (31:35–37).

Becoming a Prince

This brings us full circle to Jacob, who is renamed Israel, the “prince of God”; ultimately, Job is granted a similar experience. Early in the book, Job is described as “blameless” or “perfect.” He is a new Adam, set in a good creation. The other characters are reminiscent of Genesis as well: Yahweh; Satan, the Accuser; and even an Eve, Job’s wife.

Job’s “perfection” also reminds us of Jacob, also identified as “perfect” (Gen. 25:27). Like Job, Jacob finds himself persecuted by those closest to him (his brother, his father-in-law); the story of his life is one of struggle and wrestling. And eventually he finds himself wrestling with God himself (Gen. 32:24–30). God tells Jacob that his struggles have all fundamentally been with him (Gen. 32:28). Jacob has learned wisdom through these struggles; his wrestling has made him like a king, which is why God gives him the new name Israel, which means “prince of God.”

After he has borne his cross, and died in dust and ashes, Job receives authorization to speak before God and to intercede for his three foolish accusers. His request has been granted: He may now speak to God assured of a hearing. He may speak to him as a man speaks to his friend. Job is now one of the sons of God, a friend of God, who is granted access to the storm, to plead, to argue, to wrestle. The Book of Job is the record of one man’s growing up to wrestle with God and men and prevail.

The Path for Sons

The book thus narrates a sort of transition between generations, a transition from immaturity to maturity, from spectator to player, a point underlined by the youth of Elihu who appears at the end of the dialogues (32:6). A son watches his dad in action. He watches his father sweat, bleed, and cry. He watches his enthusiasm, his passion; he watches him wrestle and cheer. The son may face different giants, new dragons, but the son must learn obedience through his sufferings.

While the battles may or may not change from one particular generation to the next, younger Christians have no excuse for avoiding battle altogether. Because cultures sometimes change dramatically over time, any given generation may not be required to be militant on the same fronts as Christians of an earlier day. But they cannot renounce militancy as such without renouncing maturity. If Job is the pattern, the fray is the path to maturity, the path of sons and prophets.

Peter J. Leithart is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America and the president of Trinity House Institute for Biblical, Liturgical & Cultural Studies in Birmingham, Alabama. His many books include Defending Constantine (InterVarsity), Between Babel and Beast (Cascade), and, most recently, Gratitude: An Intellectual History (Baylor University Press). His weblog can be found at www.leithart.com. He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor