Kosovo Lost & Found

A Visit to Old Serbia in Search of Its Ultimate Destiny

by Patrick Henry Reardon

For both of us sitting down to coffee that morning—in an outdoor café in Kosovo—the meeting was a “first”: Never before had I spoken with a Muslim Kosovar, nor had Icuf Ukëhaxhaj ever shaken hands with an Orthodox Christian priest. It took a little while for each of us to size up the other.

I was my usual bubbly self, I suppose, but Icuf (Albanian for “Joseph”) needed a few minutes longer to adjust. Although persuaded by a mutual friend to speak with me, he insisted that the meeting take place several miles from his home, so his Muslim neighbors—historically sensitive on the matter of Orthodox Christians—would not get the wrong idea. Less than a decade had elapsed, after all, since Kosovo’s civil war, and bitter memories of that conflict were very fresh. Icuf wanted to make sure none of his neighbors thought he was “selling out” by chatting with an Orthodox priest. An Orthodox priest, in Kosovo, is normally a Serb, and a Serb, to Icuf and his Muslim neighbors, is an enemy.

Kosovo’s civil war, a final stage in the breakup of that strange political amalgam known as Yugoslavia (a modern makeshift union finally dissolved in 2006), had been particularly brutal. Although Kosovo had far more Albanians than Serbs, the government in Yugoslavia—and Serbs generally—regarded Kosovo as an integral part of Serbia. After this government revoked the limited autonomy of Kosovo in 1990, roughly 80,000 Albanian Kosovars lost their government jobs, and Yugoslavia initiated a much tighter economic, political, and cultural control of the region.

The civil war, begun in 1996, arose in response to those developments. Into Kosovo, the Yugoslav government in Belgrade sent an army of Serbs for the undisguised purpose of what we have come to call “ethnic cleansing.” As thousands were killed, tens of thousands were injured, and hundreds of thousands were forced out of Kosovo (mainly to neighboring Albania and Macedonia), the war dragged on until the air forces of NATO compelled Yugoslavia to back down early in 1999.

Everywhere I saw evidence of the war, both in ruined buildings (including numerous mosques) and in many shrines erected to commemorate the dead. These latter included not only the casualties of combat, but also the victims of random murders and systematic atrocities. I had been warned that the Kosovars would want to talk mainly about the war.

Many Meetings

I came to Kosovo, however, not to assess the past, but to gain some perspective of the region’s economic, political, and religious future. In particular, I wanted to put a personal face on the region, by meeting as many different sorts of its citizens as I could, both Albanians (at least 88 percent of the population) and Serbs (generously estimated at only 7 percent since the war).

Orthodox missionaries from America to Albania had arranged for me to interview both Muslims and Christians—the latter including Serbian Orthodox and Roman Catholics—as well as people with not much religion at all (evidently the majority). I was especially interested in learning from professional types and local leaders: businessmen (like Icuf), municipal politicians, doctors, clergy, and such. Besides several individual teachers in various parts of the region, I met the entire faculty of a grammar school in Caralug.

The future of Kosovo was the object of my inquiry. I was not interested in rehearsing the details of the recent hostilities—including myriad recriminations, indictments, and accusations of atrocity from both sides—though this painful subject was still very much on the minds of those I interviewed.

Icuf was typical in this respect. A former officer in the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), he lost a brother and many friends in the conflict and had been a prisoner for six months. I did not interrupt, much less contradict, Icuf’s personal narrative, aware that this was a first opportunity for him to pour out his anguish and grievances to someone who—being an Orthodox priest—might plausibly be taken to represent “the other side.” It was a story of great suffering, and he appreciated my listening respectfully.

Icuf’s assessment of the situation in Kosovo expressed a stern moral tone, not to say moral outrage. He regarded the Serbian claims over Kosovo, and the means adopted by Serbia to enforce those claims, as profoundly immoral. This approach to Kosovo, let me say, did not fit my plans at all; the last thing in the world I wanted to do on this trip was to make a final moral judgment about either side in the conflict. Indeed, I still hope to finish these comments without doing so. Nonetheless, in the course of examining the current situation in Kosovo, it will be impossible not to mention matters that raise grave moral concern.

Commercial Future

Eventually, Icuf was persuaded to talk about Kosovo’s future. I began that discussion by sharing with him my initial impression of the region’s great natural and geographical advantages. Kosovo was clearly a territory of vast potential wealth; anyone could see it. The land is mainly a high plateau, something over 4,200 square miles—about one-tenth the size of Ohio, if my rough calculations were close—ringed about by mountains. The latter are full of mines and quarries, a great source of Kosovo’s potential wealth. In fact, the World Bank estimates the region’s store of coal, iron, lead, and other mineral resources at 13.5 billion euros.

Inside this mountain ring, more than half the plateau is farmland, over half of that under cultivation and the remainder meadows and pastures. Agricultural authorities in Kosovo, working with British and Swiss groups, are endeavoring to improve the region’s dairy herds. In addition to extensive fields of various grains, I saw vineyards and orchards aplenty. Icuf agreed with my initial impression. “In ten years,” he said, “we will have a Balkan California.”

Coming eastward through the mountains that separate Kosovo from Albania, I had been much impressed by the ongoing construction of an immense highway, designed to stretch from the Adriatic Sea all the way to Pristina, Kosovo’s capital and largest city. Up till now, this landlocked region’s most available seaport has been Thessaloniki, far down south in Greece, but it will soon be replaced by Durres in Albania, directly across the Adriatic from the large Italian port of Bari. (I have made the voyage by ferry.)

This new westward road to the sea, which includes two long double-bore tunnels through the mountains and 27 bridges, will cut the travel time between Kosovo and the Adriatic from an all-day journey to a mere two hours. The resulting benefits to commerce and tourism are projected to be considerable. More significantly for Kosovo’s social, cultural, and political future, this new road will tie the area to Italy and Western Europe.

When this project is completed, I am confident Kosovo will also become a strong tourist attraction, especially for skiers. At prices far below the expensive Alps, Kosovo’s Shari National Park, which overlooks the city of Prizren in the southwest, offers some of the best skiing slopes in the world. Rather soon, I predict, this vacation setting, through which I came by car the previous day, will be well known to the rest of Europe.

EU Connections

Indeed, with respect to its economy—and increasingly with respect to its culture—Kosovo is already a sort of colony or outpost of the European Union. Its currency is the euro, and the apparent future of the region depends very much on Western investments and economic ventures.

As Icuf and I spoke on this subject, he mentioned the comparative youth of the population (and the highest per capita birthrate in Europe) as one of the major attractions Kosovo offers for foreign investors. This young, flexible, and abundant workforce, for which the average gross wage is only about 220 euros, covers many skilled professions, such as communications and computers. Relative to the rest of Europe, moreover, taxes are low—another incentive to foreign investment.

Kosovo enjoys a further commercial advantage in the fact that the major languages of Europe are widely spoken there. For example, I had to rely on my German to order breakfast the next morning.

Much of the region’s commerce is with the Balkan states. In 2006 Kosovo signed the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), which gave its exporters duty-free access to a regional market of more than 25 million consumers. This agreement explained, among other things, the trucks I saw carrying lumber and other raw materials south to Macedonia.

Besides this regional commerce, Kosovo has the advantage of non-reciprocal, customs-free access to the immense market based on the European Union’s Autonomous Trade Preference (ATP) regime. Thus, an enthusiastic entrepreneurial spirit of commerce was much in evidence.

There were likewise fresh construction projects on all sides, from the numerous mosques (with Saudi money) in every village to new hotels, restaurants, stores, and municipal buildings. This extensive construction, besides serving as a source of employment, indicates Kosovo’s growing economic ties with the outside world. One of the region’s largest employers is the American firm Bechtel, which joined with the Turkish contractor Enka to construct the new road to the Adriatic.

In fact, the very large workforce in Kosovo is the cause of its most serious economic problem: unemployment. I would later learn how the territory also benefits from exporting much of this labor.

Cultural Future

Commercial contacts with the West were especially on the mind of Isni Kilaj, the mayor of Malisheva, a city slightly southwest of the center of Kosovo. Unlike Icuf, Isni was not preoccupied with memories of the war, even though he had served as a brigade commander in the KLA. I had no trouble persuading him to speak of the future.

As we sat in a fine new restaurant of that city and ate a delicious lunch of several courses, Isni told me his story: Having studied economics in his youth—both socialist and capitalist—he decided the second kind was better. From 1981 to the end of the civil war in 1999, he told me, under the government of Yugoslavia, not a single new building had been constructed in Malisheva, nor a single new road. The economy was moribund and stagnant. Since the war, in contrast, no fewer than 100 kilometers of new road have been laid in the town of Malisheva, and new schools and other buildings have been constructed.

In the mayor’s view, the recent conflict between the Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo had almost everything to do with economics, and relatively little to do with religion. As evidence for this opinion, he pointed to the comparatively peaceful relations between the Muslims and Roman Catholics throughout the region. (I am aware of reasons to doubt the accuracy of this description, since most Roman Catholics in Kosovo live among the Serbs.) Considerations of the economy formed the casus belli in Kosovo, Isni insisted, not religion.

Following up on these comments on religion, I inquired about the territory’s economic and political ties to the Middle East. I mentioned hearing reports that Muslim money would be used to tie Kosovo to Arab politics. The mayor found this idea singularly funny. Nothing, he declared, could be further from the truth. Except for Saudi Arabia’s modest construction of small mosques in all the villages, those alleged financial and political ties to Arab countries were simply non-existent, he insisted. He poured scorn on the idea that Kosovo benefited very much from Muslim money or could be induced to throw in its geopolitical future with Arab causes. “Ha, what would we want from Syria?” he asked. “Syria is friends with Russia, and Russia sides with Serbia.”

Emigration & Westernization

Isni did, however, throw further light on Kosovo’s financial ties to the West by introducing the subject of emigration: The constant problem of unemployment, in a territory with the highest birthrate in Europe, obliges Kosovo to export a large percentage of its work force. From every family in Malisheva, he observed, there was at least one member currently working in Western Europe, mainly in Italy, Switzerland, or Germany. (This accounted for all the German that was about.) Since that discussion with Isni, I have seen figures as high as 25 percent to describe Kosovo’s workforce dispatched to European countries.

These emigrant workers to Western Europe travel on passports issued by Kosovo itself. Inspecting one of them, I noticed that they are printed in Albanian, Serbian, and English.

The constant emigration and return of these workers brings to Kosovo not only a sustained influx of needed capital, but the growing influence of Western ideas and cultural sympathies. Kosovo may be the most westernized region in the Balkans. (I did not venture to mention it at the time, but I wondered if this westernization was entirely a good thing. For instance, a Catholic dentist in Klina told me of a concert last year in neighboring Montenegro, where Kosovar students went and laid down 200 euros to listen to Madonna. This development, I groaned inwardly, was less than encouraging.)

Political Uncertainty

In spite of this evidence of material progress and enthusiasm for Western ideas, the political future of Kosovo is anything but certain. Since its provisional government declared independence from Serbia on February 17, 2008, the international response to that declaration has been mixed. While more that fifty countries now recognize Kosovo as an independent nation, three times as many do not. Moreover, in October of this past year, the UN General Assembly approved Serbia’s proposal to request a judgment on the matter from the International Court of Justice.

Notwithstanding the region’s growing economic ties to Western Europe, five countries of the European Union, including Spain, do not recognize Kosovo’s political independence. One suspects that this circumstance, all by itself, would be an insuperable obstacle to Kosovo’s entrance into the European Union. Meanwhile, Serbia will certainly become a candidate for membership in the EU, perhaps as early as this year. Now, if Serbia—still insisting that Kosovo is part of its territorial integrity—were admitted into the EU, where would that leave Kosovo? With respect to the liberal politics of the EU, on the other hand, I confess to a measured lack of confidence.

Although the new democratic government of Serbia has vowed to deal with the Kosovo problem only through diplomacy, I wonder how many believe it will. So far at least, European governments show no disposition to withdraw from the NATO-led security force (the Kosovo Force, or KFOR) that currently preserves the peace in the region. How long, nonetheless, is Europe prepared to maintain a military presence in Kosovo? On the whole, Europe manifests little sympathy for long-term military commitments.

The Fate of “Old Serbia”

In short, it is not obvious that history is on the side of political independence in Kosovo, notwithstanding the vast numerical superiority of Albanians in that region. Its long history is too complex to rehearse here, but it is important to know that Serbia had long been accustomed to thinking of Kosovo as an essential part of its historical inheritance. Indeed, it is the native homeland of the Serbs, often called “Old Serbia,” a name reflecting a presence on that fertile plateau for more than a thousand years. By comparison, the political removal of Ohio from the United States would be a very small task beside the alienation of Kosovo from Serbia. Or, try to imagine Belgians taking over all of France on the right bank of the Seine. I mean no disrespect, but Serbs can be very tough customers. From my many friendships with them, I suspect that they are prepared to oppose the independence of Kosovo for the next thousand years.

At least the Serbs give that impression. In a lecture delivered in Chicago this past June 10, I heard Serbia’s Consul General, Desko Nikitovic (an engaging and eloquent man, by the way), describe Kosovo’s declaration of independence as an “attempt to hijack history,” and he went on to declare, “Any Serbian leader speaking in favor of the independence of Kosovo would be committing political suicide.” Doubtless he was right.

Notwithstanding such public expressions of political resolve, I must confess a persistent doubt about Serbia’s hopes for the future of Kosovo. I was especially impressed, in this regard, by two marvelous teenagers in a Serbian village near Pristina, a boy and a girl, both of them gifted well beyond the ordinary. They announced—the girl in flawless English—that they had no intention of spending their lives in Kosovo. They would leave upon reaching their legal age, they declared, and settle somewhere else in Europe, maybe France—anywhere but Kosovo. Constantly feeling both despised and unsafe in the midst of an Albanian majority, they were unable to imagine living like that forever.

No matter how often or loudly I hear Serbian leaders declare their resolve never to give up Kosovo, I will recall those two children and suspect them to be typical. Now, if the cream of that Serbian generation is lost to Kosovo, it will make no difference what resolutions are expressed in Belgrade, at the Hague, or in the UN General Assembly. If the children in that generation are lost to the region, the Serbs of Kosovo will follow the Greeks of Asia Minor in the long sad saga of cultural tragedy. I say this sadly and by way of hypothesis, not as prophecy.

Serbian Concerns

Although I started with the Albanian Kosovars in writing these reflections, I actually began and ended the trip by meetings with the Serbs in Kosovo. Among these, I found not the faintest trace of the energetic, adventurous, optimistic, and entrepreneurial outlook that was obvious in the Albanians.

On the other hand, there were deep differences of attitude among the Serbs, covering a range from a piercing defiance to a pervading hopelessness and despondency. Ironically, it was among the defeated Serbs, not the prevailing Albanians, that I discovered the most serious moral probing of the current situation in Kosovo. Indeed, it was from the sorely pressed Serbs, not the enthusiastic Albanians, that I heard the gravest moral questions raised with respect to Serbia’s place in the history of the region.

The Serbian minority in Kosovo, most of them living in enclaves and neighborhoods protected by the KFOR, have a very hard life. It is really not safe for Serbs to wander about in other parts of the region, so they generally don’t. A state of siege is probably the best description of their situation. “It has been hell for the past ten years,” one Serb told me.

Because of American and European foreign policy and military intervention—bitterly resented by the Serbs, of course—this part of the population is much worse off after the recent war. For example, during the years just prior to that conflict, Kosovo had provided refuge for thousands of Serbian exiles who were dispossessed and driven from Croatia, Slovenia, Krajina, Bosnia, and other parts of collapsing Yugoslavia. There were a half-million Serbian refugees just from Croatia. With the coming of the war in Kosovo, however, these same immigrants again lost their homes and were obliged once more to flee. Others were compelled to abandon farms their families had cultivated for many generations.

Deliberate Destruction

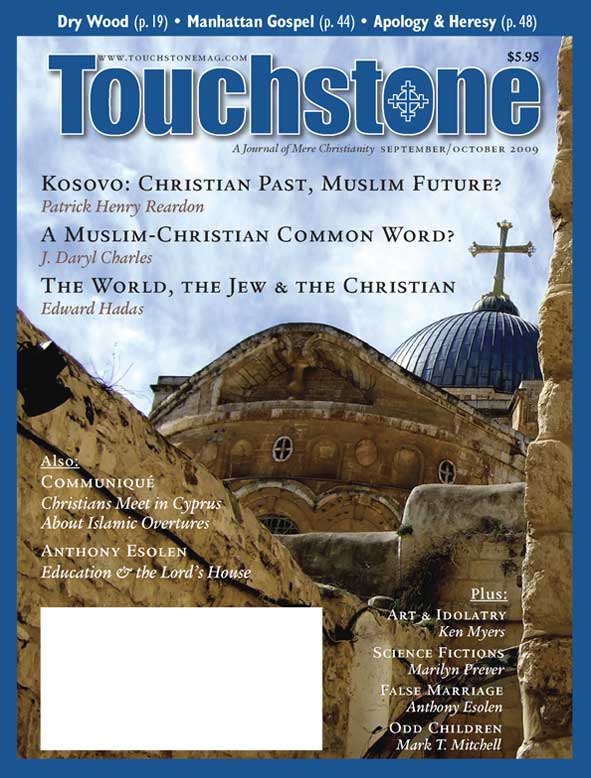

Thousands of churches and hundreds of monasteries dotted the land in strong testimony to Serbian historical claims over the region. The southern part of Kosovo is commonly called Metochia, a name meaning “monasteries.” In fact, among the places in Kosovo I was privileged to visit, the two most special to my heart were the fourteenth-century monasteries of Gracanica, just a few miles south of Pristina in the east, and Decani, near the western border. Now surrounded by disapproving Albanian populations, both monasteries survive under constant military protection—the Italians at Decani and the Danes at Gracanica. The monastics in these communities live in painful isolation, which they feel keenly and were not reluctant to share with me. These monasteries made the deepest impression on my thinking about Kosovo.

The subject of churches and monasteries is particularly smarting to the Serbs, because approximately 135 of those structures—most of them centuries old and regularly the sites of pilgrimage—were destroyed by the Albanian Kosovars. Moreover, this destruction took place, not in the heat and turmoil of combat, but coldly and deliberately, after the war was over. That happened between June and October of 1999, when the sites were already under the supposedly guaranteed protection of American and European security forces. In Crucified Kosovo, a popular published account of this disaster, each story of a destroyed church is marked by the flag of the nation that was supposed to be protecting the site. The American flag appears in this book 21 times.

Why this wanton ruin of Kosovo’s most precious cultural monuments? Very simply, because those churches and monasteries bore too powerful a testimony to Kosovo’s Serbian past and too compelling an argument supporting Serbia’s present claims over the region. The Albanian Kosovars—and here there comes forcefully to mind a long conversation with several Muslims in a home in Tërpezë e Ulët—are quite resolved to break with the Serbian past.

A Divided City

Mitrovica, in the north central part of the region, is arguably the most fascinating city of Kosovo. At least it was for me. It was worth the whole trip. Arriving there somewhat after sundown at the end of an arduous day, I felt certain we had strayed—my two friends and I—onto the set of a Jason Bourne spy thriller.

Never can I forget the mis-en-scène at Mitrovica. The waters of the Ibar River—sluicing eastward toward the Morava and then to the distant drainage system of the Black Sea—slice the city into north and south. Eighty thousand Albanians inhabit the south, half that many Serbs the north. Residing on either side of that wide and shallow stream, two different worlds look across at one another with narrowed gaze and deep distrust.

Arriving in an automobile with Albanian license plates, we prudently parked on the Albanian side, on a shadowy street, before crossing the bridge (one of three) that joins Mitrovica’s two sections. Strolling over the river to the Serbian part, we came to what could have been a different planet: Whereas the Albanian district had seemed quiet and immersed in shadows, there was considerable activity and nightlife in the north. Small groups of people gathered everywhere. Laughter abounded on the streets, outside the numerous restaurants that did a lively business.

Perhaps half the population of Mitrovica’s northern section—twenty thousand or more—was made up of Serbian refugees from elsewhere in Kosovo. They lived in the new and very tall apartment buildings that converted several streets into deep, narrow canyons.

Here to Stay

A high and solemn presence oversaw the whole: Atop the hill dominating the northern landscape, stands the majestic Church of St. Demetrios, named for Mitrovica’s traditional patron saint. (“Mitrovica” is a rigorously compressed derivative of Demetrii Civitas, “the city of Demetrios.”) This church, less than five years old, replaces one destroyed on the other side of the river.

Constructed on a grand scale and adorned with several Byzantine cupolas—the whitish stucco brightly illumined against the dark sky—this shining beacon on the hill announces to all the world, “We Serbs are here to stay!” (I found it easy, gazing at that church, to remember that St. Demetrios was a Roman solider, and that Orthodox iconography generally portrays him gripping a spear. A Serbian friend of mine in Ohio, claiming that “we Serbs prefer saints with attitude,” pointed out that Serbia’s patron saint, the Archangel Michael, is also invariably pictured holding a weapon.) De facto, and no matter how the UN draws the map, the southern border of Serbia still extends well into the territory of Kosovo. Though I cannot predict the future of the rest of Kosovo, it is impossible to imagine the Serbs ever abandoning the land north of the Ibar River.

Along with the monasteries, Mitrovica seems also to be a cultural center of Serbian Kosovo. After the war, the Serbian faculties of the University of Pristina were relocated there. In fact, a member of the medical faculty was our host for the evening.

Dr. Ivan Radic is a big and brawny man in his early thirties. He is also very bright, extremely friendly, and full of life. After guiding us through the grand tour of the northern downtown, he brought us to a small restaurant for a late supper of roasted fish. To rouse our flagging energies for the latter effort, Ivan introduced us to a sharp quince brandy called dunja.

Apparently familiar on a first-name basis with everybody in Mitrovica, and evidently representing just about every soul north of the Ibar, Ivan was robustly defiant in support of Serbia’s claims to Kosovo. Though he manifested not the faintest trace of anger or resentment, he insisted that only the UN had a legitimate mission in the region, and he regarded the presence of NATO forces as completely illegal. He also mentioned a point I should have suspected—namely, that neither the dictates nor the muscle of the Kosovo government are taken seriously in the Serbian enclaves.

Meanwhile, the resources for Serbian schools and other services in Kosovo come from Serbia. Serbian enclaves won’t take a cent from the government in Pristina. Its authority is regarded—with disgust—as only a temporary usurpation. “Most Serbs believe it will last for only a few decades,” said Ivan, “Once America loses interest here, the independence of Kosovo is a thing of the past.” The implication was: America will eventually lose interest here.

Moral Considerations

Because Ivan’s was the most forceful and eloquent voice I heard in support of Serbian political claims over the region, I was obliged to take seriously his single grave reservation regarding Serbia’s moral authority in the current standoff. This reservation had to do with the low birthrate of the Serbian population, and especially the matter of abortion.

Although the Serbian birthrate in Kosovo is higher, Ivan said, than in Serbia, Bosnia, Croatia, and elsewhere, it is still far below that of the Albanians, whether in Albania or in Kosovo. “We lost this war in the bedroom,” he declared. Whereas the Serbs in Kosovo had greatly outnumbered Albanians prior to World War II, the situation was reversed during the second half of the twentieth century. He explained: “While the Albanians were obeying God’s law—and reaping God’s blessing—to increase and multiply, the Serbs were practicing birth control and abortion.”

Although the Serbs’ accusers have often indicted them for genocide against their neighbors, Ivan ventured the startling view that Serbia’s major genocide was carried out against its own population. Serbs murdered far more Serbs than they did Albanians. Since World War II, the Serbian Orthodox Christians of Kosovo have slaughtered much of two generations of their own unborn children, while the Albanians, in that same region and during that same time period, boasted the highest birthrate in Europe. These figures, I believe, represent the most serious challenge to Serbia’s moral claims in Kosovo.

Indeed, long before my coming to Kosovo, the incidence of abortion in modern Serbia had been at the top of my concerns. According to the “Serbia Forum” and other online sources (for example, www.blic.rs/drustvo.php?id=14216), that country still has the highest abortion rate in Europe, followed closely by another Orthodox Christian country, Greece (cf. Alexander Halkias, The Empty Cradle of Democracy: Sex, Abortion and Naturalism in Modern Greece, published by Duke University Press). The frequency of abortion in other countries traditionally Orthodox—Russia, Romania, Bulgaria—is likewise distressing.

The policies of Communist governments are often blamed for the frequency of abortion in Eastern Europe. In my opinion, however, this is not a compelling explanation. For starters, it obviously and emphatically does not apply to Greece. Nor does it explain why two other places in the region—Albania and Yugoslav Kosovo, both of them ruled by brutal Communist regimes until recently—have maintained the highest birthrates in Europe.

No, the blame for the problem of abortion in Eastern Europe cannot be solely, or even mainly, ascribed to liberal politics. This is first and last a spiritual and moral failure of the culture, insufficiently addressed from the pulpit and in pastoral pedagogy. Does not this prodigious failure, prima facie, represent an indictment of the moral authority of the Orthodox Church? A dilemma of this magnitude, I submit—the innocent blood staining the ground and crying out for heaven’s attention—is of vastly greater moral weight than the question of who, in the end, will rule over Kosovo.

The Church

And this consideration brings us to the Orthodox Church in Kosovo.

With respect to healing the wounds of the recent war, the most radical suggestion I heard came from an Orthodox priest in the region. He proposed that the Orthodox hierarchy should invite the Muslim leaders in Kosovo to accompany them around to every site defiled by an atrocity, no matter who committed it. At each of these sites, this priest went on, the Orthodox hierarchs and the Muslim leaders should ask pardon from one another and declare a solemn resolve that such things would never be done again. They should embrace one another in friendship and pledge to work together for the healing of Kosovo.

This proposal sounded fine to me. Why not do exactly that? Because, the priest responded, “the day I gave public voice to such a proposal would probably be my last day in the priesthood.”

Kosovo is often described as a Muslim region, but it is not, really. The atmosphere and culture are overwhelmingly secular. For this reason, the Orthodox Church in Kosovo, answerable to the Patriarchal Synod in Belgrade, has a very large task of evangelism on its hands, if it will begin to consider this historical opportunity. To gain a better grasp of these things, I had hoped to meet with the Orthodox bishops in the region, but both of them were, unfortunately, out of the territory while I was there.

I found a single gaping division among the Serbian Orthodox Christians in Kosovo. Indeed, it was obvious almost from the start. Crafted in broad categories, which would require many nuances and refinements for a more complete picture, here is my assessment of the deep split among the Christian Serbs of Kosovo:

A large part of the Orthodox Church in Kosovo—perhaps the larger part—is dominated by concerns of ethnicity. Taking its cue from the political climate of Serbia, it pays scant attention to the gentler impulses and more evangelical sympathies of the Holy Synod in Belgrade. Heavily influenced by a spirit of Serbian nationalism, this part of the church shows virtually no interest in evangelizing and baptizing the great masses of Kosovo’s secularized population. It has not bothered to learn the Albanian language. It hunkers down (a thing easy to do when you are surrounded by hostile neighbors) and waits for the return of Serbian rule over the region.

If this spirit prevails, Kosovo may indeed become Serbian again, but I fear the Orthodox Church there will have lost its way. The missionary interests of the church are not co-terminal with the national aims of Serbia, nor is the political future of Kosovo as important—to God, the Lord of history—as the eternal salvation of those who live there.

The Monks of Decani

There is another part of the Church in Kosovo, however, which has already started preparing for the spread of the gospel to the rest of the region. These people are less concerned that Kosovo should become Serbian than that Kosovo as a whole should become Christian.

It seemed to me that the monks of Decani, some of whom have learned to speak Albanian, form something of a vanguard in this forward-looking movement. Although they insisted on the legitimacy of Serbia’s political claims in the region and showed not the slightest enthusiasm for Kosovo independence, the Decani monks manifested a greater interest in the salvation of souls—including Albanian souls.

Indeed, even during the war, the monastery of Decani was a beacon of hope and renewal. When hostile Albanians launched a mortar attack against the monastery, and bombs from American planes (evidently misdirected on purpose!) fell on the monastery’s apple orchard, the monks of Decani went on with their traditional routine: chanting the Psalms and hymnody in church, painting icons, studying the Bible, tilling fields, gathering honey, making cheese and butter, and so on.

And especially these monks loved their neighbors, regardless of race or religion. When the army sent from Yugoslavia was killing and pillaging all through the region, the monks of Decani received the fleeing Muslims and other Albanians into their cloister to protect them. These monks—never more than thirty in number, I think—fed the hungry and housed the homeless. When cursed, they blessed. Slapped on one cheek, they turned the other. That is to say, they did what Christians are supposed to do in the hour of the gospel’s testing. They placed the gospel first. If the spirit of the Decani monastery prevails in the Orthodox Church in Kosovo, I believe nothing is to be feared about the region’s future.

Gratitude & Blessing

I beg indulgence, finally, to close these remarks by expressing deep gratitude to Nathan Hoppe, a member of our parish in Chicago and an Orthodox Christian missionary to Albania, and to his wife Gabriella, a native Albanian missionary to her own people. They are the ones who arranged the numerous contacts for my interviews with the citizens of Kosovo and carefully prepared me for those encounters. They accompanied me on the trip, Nathan serving as my driver and guide, and Gabriella translating between English and Albanian.

This couple, as emissaries of the Orthodox Church in Albania, have no apostolic commission to preach the gospel in Kosovo. For more than a decade, nonetheless, they have worked extensively to forge good and kind relationships with all manner of people in Kosovo, building bridges of friendship, understanding, and compassion, in order to reconcile people whom evil forces in history work hard to tear apart. May Christ our dear Lord pour his benediction richly on their efforts. •

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor