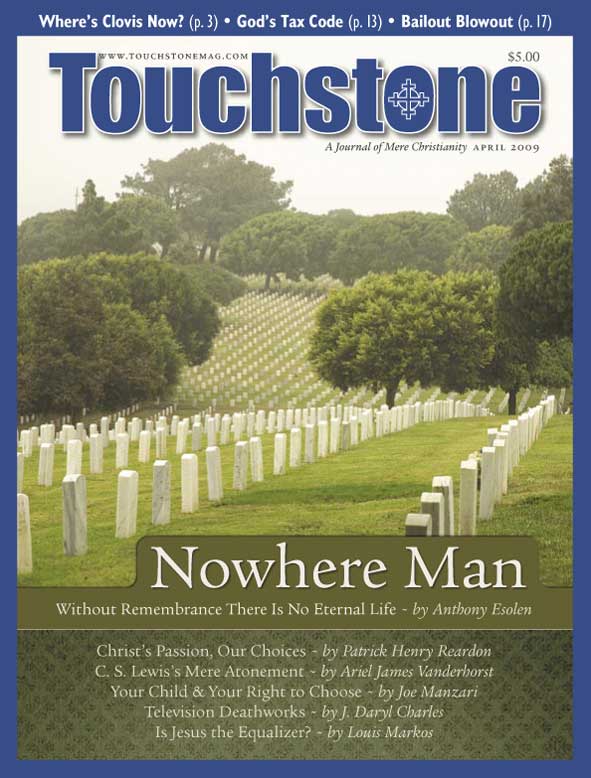

Nowhere Man

Without Remembrance There Is No Eternal Life

by Anthony Esolen

Behold,” says the Psalmist, “I searched for the place of the wicked man, and it was no more.”

The ancient Hebrews, it is commonly said, believed that the dead would go down to a shadowy place called Sheol, a realm of next-to-nothingness. “Can dust praise you?” cries David, pleading that God should vindicate him before he dies, as it would be to no avail afterwards. Even so, death was not the most dreadful fate they could conceive.

“Man dies, and his place knows him no more.” It is the second clause that expresses the greater dread, of a death beyond death. It is the terrible prospect of a total and unalterable severance—expressed as a loss of place. How should it be, if one were wiped clean from the memory of earth and heaven and all that dwell therein? How should it be, not to cease to live, but to have one’s few days of life delivered over—in their essence—to nothingness?

Alien to All

That is a foreshadowing of the doctrine of hell. It is also, I think, what modern man has accepted, somewhat uncomfortably, as his lot in life. He fears death, true enough, and seems ready to squeeze out a few final years by cannibalizing his offspring, farming human beings for spare parts to gerry-rig the rickety machine he has resigned himself to being. Yet he cannot understand, or will not confront, the Psalmist’s dread. That is because he already has no place: His u-topia, his no-place, is the price of his autonomy. He has made it the cornerstone of his ways and days. Search for modern man, and you may find him, for a while—anywhere, nowhere in particular.

I don’t simply mean that modern man moves about a lot. He does that; he conveys his body from place to place, or from subdivision to subdivision, whose streets are like little commercials, naming no revered man or celebrated victory, but “Julie” and “Dana,” or the trees that had to be cut down to build the thing. Such no-places resist roots, and that suits him fine. He draws enjoyment from his travels, as he’s a butterfly of a tourist, but he would scoff at the suggestion that he should belong to and love a certain place in return for the nourishment it has provided him. What nourishment? From earliest youth his strongest place-memories are of styrofoam: nowadays the garish colors of the daycare, the speckled tiles of a drop ceiling, the smell of cleaning fluid on linoleum, the ketchup oozing through the pores of one more hamburger bun among billions and billions.

He “chooses” here or there according to his autonomous taste, and that reduces his place already to insignificance. The philosopher Philippe Beneton puts it well: We are all different, says modern man, and the differences make no difference. I may choose to live in the Loire valley, because my caprice inclines me to rolling countryside and quaint little empty churches. Tomorrow I may choose the Arizona desert. It makes no difference. Any land is mine, because I am equally alien to all. I am the inverse of the old French peasant, whose boots might never have pressed the soil twenty miles beyond his farm and village, but who knew his home, as his home knew him.

Knowing One’s Time & Place

And who is the braver traveler? As a man’s commitment to love this woman, to cleave unto her alone until death shall part them, is not the end of love’s journey but its most adventurous onset, so it may be that a man’s commitment to one place—and by “place” I mean more than locale, as I will explain—fits him best to embark upon the pilgrimage. Even when he travels abroad, modern man is a commuter. The termini of his life are not birth and death, but this anywhere and that anywhere.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor