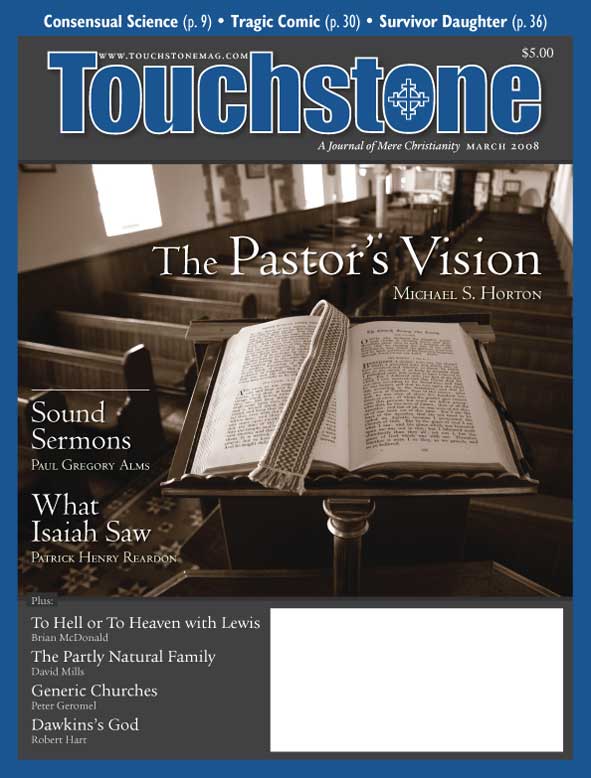

Editorial

The Word Through Us

The Difference Between the Bible & the Koran Is Fermentation

From early times, Christians have observed March 25, nine months before Christmas, as the day when “the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.” This is a good occasion to reflect that the dogma of the Incarnation is not just one of the teachings of the Christian Church. The Word’s assumption of our humanity may be described, rather, as the structural principle, a kind of Formal Cause, of the Christian revelation.

It contours the Christian religion in all its elements. Perhaps we may speak of an “Incarnation Principle,” according to which the sundry components of the Christian faith are formally determined.

Contrasting Principles

To illustrate at least one aspect of this Incarnation Principle, it may be useful to contrast the Christian religion with the world’s second largest religion, Islam. I propose to do this with respect to the very notion of Revelation.

According to universal Muslim teaching, Muhammad received the contents of the Koran by direct dictation from the Archangel Gabriel. It is the unmixed word of God, according to this belief; it is in no formal sense the composition of Muhammad.

That is to say, the Koran’s message in no way entered into or came through the creative literary powers of Muhammad himself. He simply wrote from dictation, word for word. In this sense, the Koran remained external to him. Muhammad was not its author. All Muslims agree on this.

This Muslim view of “Revelation” is radically alien to what the Christian religion means by the same word. What is missing in Islam is what I have called the Incarnation Principle. That is to say, we Christians believe that God does not speak to man in a way that remains exterior to him. We do not believe that divine Revelation was simply “dictated.” The biblical God is not a dictator.

On the contrary, according to Christian theology God speaks to man through the inner creative workings of his mind and heart. In that inspiration by which God caused the Holy Scriptures to be written, man himself was a co-worker with God, a synergos. God’s word is likewise, then, the word of some human being who is properly called an “author.”

Thus, we believe that the teaching of the Pentateuch is not simply the word of God, but also the word of Moses. We contend that God spoke to Moses through divine inspiration, a Spirit-breathed process that included the thinking and imaginative powers of . . . Moses. The Incarnation Principle means that God’s word was filtered through—digested by—fermented in—the mind and heart of a human author.

The Word Assumed Flesh

Revelation comes to us, accordingly, through the inner anguish of Jeremiah, the soaring minds of John and Isaiah, the probing questions of Job and Habakkuk, the near despair of Qoheleth, the structured poetry of David, the disappointments of Jonah, the struggles of Nehemiah, the mystic raptures of Ezekiel, the slow, patient scholarship of Ezra, the careful narrative style of Mark, the historical investigations of Luke, and that pounding mill, the ponderous mind of Paul.

According to the Incarnation Principle, God’s word finds expression in inspired literature, because it first assumed flesh in human thought and imagination. This truth is indicated in that vision where Ezekiel sees God’s word on a scroll that he must eat. That is to say, God’s word always comes to us in a fermented, pre-digested form.

This element of fermentation in God’s word prompts me to liken it to cheese and wine. Perhaps we may think of the authors of Holy Scripture as various fermenting agents, each of them bringing a distinctive flavor and consistency. The Incarnation Principle is what causes Proverbs to taste like a robust Cheddar, for example, while the Song of Solomon feels more like Havarti.

Among the Psalms, we discern both Cabernet and Sauvignon, and among the Gospels we revel in everything from Port to Muscatel. Or, moving from the Pentateuch through Joshua, Judges, and Samuel, let us think of it as an adventure going from Chianti to Bordeaux, Chablis, and Beaujolais. Or, to return to cheese, let us think of the weary reader growing tired of the Cheshire of First Peter. Well then, along comes James with a bit of Brie, or maybe Paul to spread a plate of Podravec.

This fermentation theory may even settle some touchy exegetical concerns. For instance, if we think of the Chronicler’s story as a kind of Swiss, this would account for the narrative holes in his work.

These blessings, in short, all taste different, because God’s Word, which is our food and drink, has already been incarnated in—has passed through the digestive processes of—the human heart, the inspired mind and imagination of man. We always receive the Word of God as the word of men.

The fermentation process recorded in biblical literature has its counterpart in Christian history. The gospel is not forcefully imposed on society. Human cultures are not simply told, “Here are the rules—Now measure up!” Unlike the Koran, which was imperiously enjoined on history from without, the gospel has assumed sundry shapes and called forth greatly different applications throughout the centuries, as required by various social, economic, and political circumstances.

Unlike Islam, the Christian body has already recorded its ability, over a long time and in many places, to take distinctive configurations in national and regional cultures vastly different among themselves. It is a fact of history that the community of peoples formed by the gospel has demonstrated a social suppleness and cultural flexibility enabling it to transform nations and tribes from within. There is every reason to think that this will continue to be the case.

We are not so sure, however, that Islam can develop the same degree of social and cultural flexibility, because up till now there has appeared among the sons of the Prophet nothing comparable to the historical pliability rooted in the Incarnation. This Mystery of the Christian faith, God’s assumption of our humanity, remains a deep, real, and abiding difference between us.

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Islam from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor