Losers Keepers

The Liberating Power of Negative Thinking

by Annegret Hunter

I am a loser. Oh, there is no doubt about it. I read it recently in an article. Some feminist writer thinks that being a mom at home is “not worthy of the full time and talents of intelligent and educated human beings.” The tasks of moms at home “do not require a great intellect, they are not honored and they do not involve risks and the reward that risk brings.”

There you have it. I always had the sneaking suspicion that I should have followed my youthful passion and become a race-car driver—think of the risks involved! But no, I had to park not just my race car but also my brain, for I married, had children, and ended up taking care of the family, and what did I get from that? Motherly memories, which, although they are devoid of talent and intellect, I nevertheless do cherish.

A Little Shabby

For example, there is the first outing alone: just a cup of coffee with another mom. One more kiss for the baby, one more time holding him to your shoulder and rubbing his soft little back, then you are out the door, only to discover, at the café, that he had puked down your back, which you desperately pretend not to notice, while you decide not to tell your friend she is wearing her skirt inside out. You talk about nothing but babies, of course, and the moment you hear a baby crying, anywhere, you liquefy.

Or you take the bus, carrying in your arms your beautiful baby, who starts pointing at some guy and trills: “Dada, Dada,” and you, red as a tomato, flee from the bus and walk the distance to the store, where the saleswoman coos over the little darling and asks whether you are the grandmother, and you don’t even have enough energy to strangle her. Or while enjoying adult conversation at a dinner party, you absent-mindedly turn to your neighbor on the left and cut his meat into little pieces, and gently put down the hand of your neighbor to the right, because he is pointing with his knife.

Pondering the feminist writer’s (just can’t think of her name!) intellectual life, her razor-sharp mind and insights, her many publications, I feel a little shabby in comparison. And it is true that one is not honored anymore: “There she goes with her kids. Gave up everything just to be with them. What a waste!”

The business of risks and the remarks thereon, however, I do not quite grasp. The feminist writer (what was her name?) was neither a firewoman nor a war correspondent, and I do not think that being in women’s studies is any more risky than bringing up a family, but I am probably missing something.

Before we had children, some friends of ours had two little ones, the appropriate number. Both parents were important professionals, and had the family routine planned out and functioning perfectly. They had found a lovely lady down the street who took the kids even when they were sick, before and after daycare. The children were very happy there, and the parents could work long hours.

After a year, they were giving up jobs and city, moving away from it all, and being pregnant again. “What happened?” I asked, standing bewildered in the living room amongst boxes and suitcases, the kids chattering, giggling, and jumping on their dad, who laughed and swung them around and around, and the mom looked at them with happy eyes, and said softly: “We thought things were going so well, until I noticed that the children were calling the other woman ‘Mommy.’ I did not want to lose them; I could not take that risk.”

A Feminist Education

Of course I was not always a loser, and I certainly considered myself a feminist, even after I was married and had started my own business.

My feminist education started with one of my clients, a devout feminist, whose visits I dreaded, because I had nothing to say to her, and she considered me an unmitigated bore. Only when my husband entered the room did she come out of her stupor and was lively and charming, and showed not the slightest aversion to seeing me, a woman, working in the kitchen.

Well, she moved away to another continent, and my husband and I, having had a spot of trouble with a drug-dealing neighbor, thought it wise to disguise our phone directory entry by using my maiden name for a while. And would you believe it, this changed entry was noticed by our faraway feminist friend, who wrote me a letter, congratulating me on my divorce, pointing out that she had known all along my husband was a cad, and rejoicing in my taking back my proper name.

Thus I learned that it is not enough to claim to belong to the sisterhood, you also must act according to the creed. I had already blundered on its first rule: “Thou shalt not ever take your partner’s name, or, if you feel like changing your own, pick some new, emancipated-sounding name that expresses your inner woman.” (Our feminist friend actually did exactly that, which prompted me, in all innocence, I assure you, to send her a congratulatory note on her marriage.) And as for the second rule, no divorce for me, thank you very much, I was taught to keep my promises.

A Different World

Now, the feminist sacrament, abortion, is perhaps where the involvement of “risks and the reward that risk brings” comes in: “A pregnancy is not a disaster any more. It is just a piece of tissue that can easily be removed, and you can go on with your own life.”

Yes, I believed that too, until my friend and I went on a trip together. We both were in business, both very successful, both independent and in command of our lives, both with supportive, professional husbands, but she had offspring: two wanted children.

We had a wonderful time on our way there, and when we stopped for coffee, my friend dropped the bomb: “By the way, I’m getting a divorce.” “What?” I yelled. “Why?” “He’s been cheating on me,” she said. “Oh, I’m so sorry,” I murmured. “Don’t be,” she shrugged her shoulders, “We haven’t been in love for years now, and I don’t want to see him anymore.”

“But what about the children?” “They are with me during the week, but they can decide for themselves, they are old enough,” she said. “Wait a minute,” I interrupted. “Aren’t they in their early teens?” “My daughter just turned fourteen. And she is a busy girl, going out every night.” “At night?” I echoed. “How can you allow that?”

“Look,” she said kindly, “the world is different now. I was young and stupid at that age, and so were you. But today girls are much more advanced, they know so much more, and they need to hang out, to experience things, you know, have friends, try out drugs, different lifestyles. They have a right to it. I’m not going to take that away from her. In any case, even if I wanted to, I couldn’t.” She grinned at my open mouth. “It’s her life, you know.”

“But the terrible dangers you let her go into every night,” I insisted. “No, no, she knows how to take care of herself, and the crowd she’s with now is okay. Last year’s bunch I did not like. They were drug pushers, and she did come home pregnant.” I was too dazed to speak. “Out of the blue she told me one morning that she was pregnant,” she went on, a little ruefully.

“And did you bring her to the clinic?” I asked, appalled. “Oh no, she didn’t want me there. It was all arranged by the school nurse and taken care of. I told you my daughter was independent.” I stared in horror at my friend, who smiled wistfully and looked into the cup she was holding.

Slowly her smile faded and the cup started to rattle against the saucer. Her hands were shaking. She bent her head, let go of the cup, and covered her eyes. “I begged her not to do it,” she whispered. “I pleaded with her. I offered to take care of the baby, to bring it up, anything, anything. I begged her for the life of my own flesh and blood, my grandchild.”

And so I understood what it means to be a feminist, and who a woman’s most dangerous enemy really is.

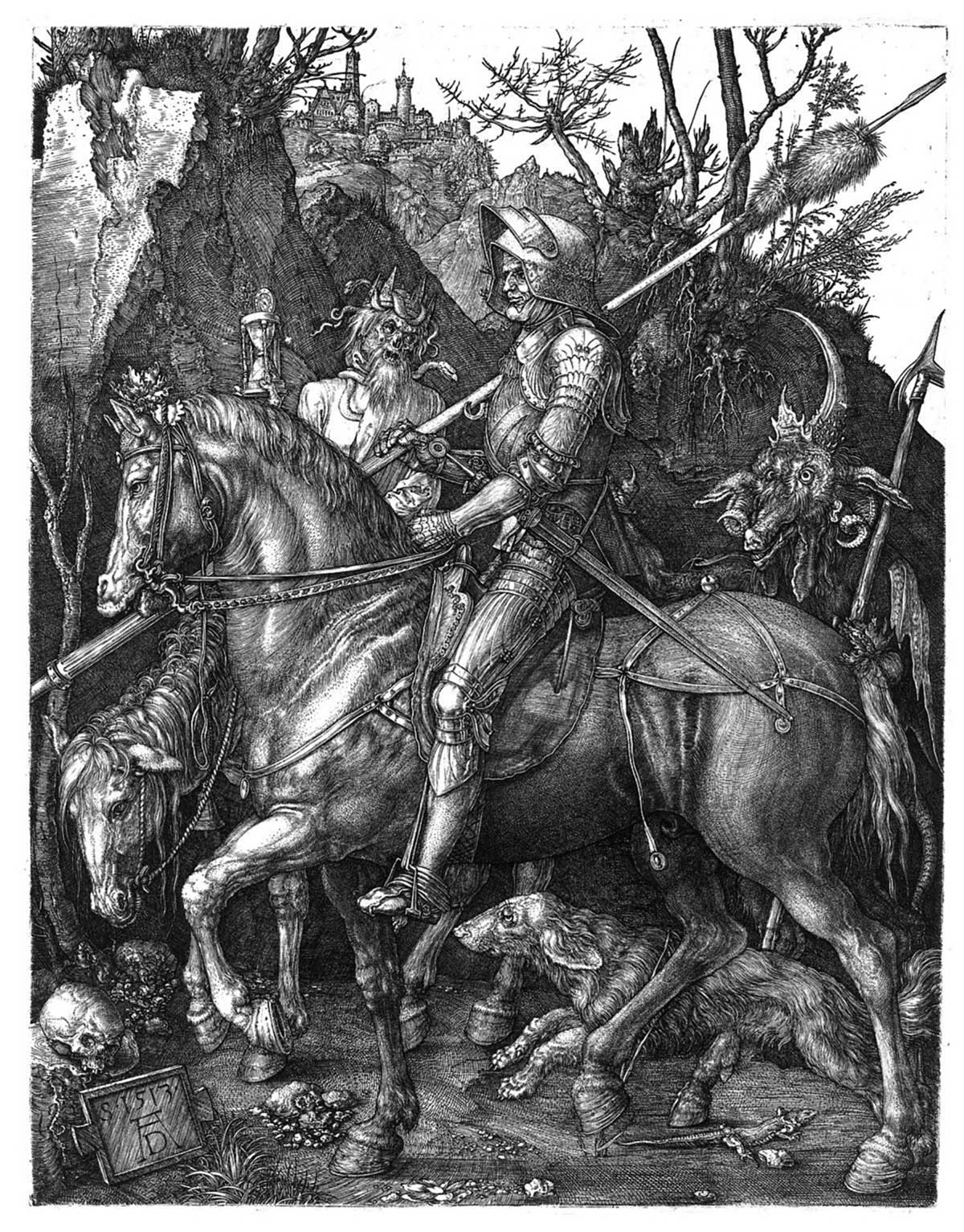

The Loser’s Net

I embraced being a loser wholeheartedly, and was shortly thereafter caught in the net by the Fisher of Men, and any former colleagues who thought that I still had some intelligence left abandoned all hope. Strangely enough, their loss was my gain: hope and joy.

After many years, I recently saw one of my old chums, married but childless, who is a master of his craft, acclaimed, admired, and adored. He looked resigned and lost. “I don’t like people anymore,” he confided. “They disgust me. I like nature, but man is destroying everything. It couldn’t be fast enough for me, you know. I hope for the end, the sooner it comes, the better.”

What a sad life that is, while amongst riches and success, sliding down into the pit of despair. But a Christian loser has the Lord on his side and the Spirit in his heart. Hope and joy are with him, even in the tightest spots.

Imagine, for instance, everyone’s most ghastly nightmare: You wake up in the locked psychiatric ward of a hospital, strapped to a bed; you cannot speak, and the doctors believe you a violent, demented madman. This was the situation in which my father found himself after his stroke. When his daughters arrived on the scene, the paperwork to commit him into a mental institution was already finished.

My sister immediately jumped into action, fighting for our father’s release through the official channels, while my nine-year-old son and I, having come across the ocean, spent the days at the hospital, locked into the ward, to be with Grandpa.

It was the scariest thing that had ever happened to me, yet my young son thought it a great adventure, was delighted to be with his adored Grandpa, and treated everyone with his customary cheerfulness and friendliness. In the evenings we trudged back, utterly exhausted.

How could I fill the many hours of confinement each day? I read the Bible. My father was not a religious man, but he listened intently, and it was the Psalms he wanted to hear, over and over again. His grandson, blessed with an extraordinarily beautiful boy soprano, and also a member of a Gregorian Chant choir, sang for him all the hymns and chants he could remember every day.

We got quite a reputation, my son and I. Mind you, it was not a flattering one: “Mom, what’s a ‘raving fundamentalist from America’?” The staff, right down to the cleaning lady, were unbelievably cold and patronizing to me, but they grudgingly liked the little singer, and the inmates openly adored him.

The Other Men

There were three other men in my father’s room. The one at the far wall never spoke, just lay there on his back, moaning softly, his eyes open but only the white showing. He did not react when spoken to. “He’s a vegetable. Hopeless,” the others said. Yet I noticed one day that he had stopped mumbling, and that his eyes were actually focused on our songbird, who was chanting the Pater Noster in his sweet, strong voice.

The second man was young, lively, and a druggy, as he cheerfully admitted. He loved to tell tall tales of his terrific travels in America, and was spurred on to shameless levels by his spellbound little listener. When the nurse came to fetch him, he would skip and dance out the door.

They would carry him back, later, and put him to bed, where he would lie twitching, and stare at the ceiling. Our songbird’s chanting gave him relief also, because he would stop shaking, his eyes would close and his body relax.

Of the third man I was very afraid and would never let my child near his bed. A weasely fellow he was, usually just lying with his back to us, looking at the wall. Small, sandy-haired and pinched-faced, he could only snarl, and his eyes were replete with raw, naked hatred.

“How can you believe in all that claptrap you are reading?” he would sneer. “Lady, you are such a stupid loser, you ought to be locked up like the rest of us. You really think you can get your old man out? Don’t you understand that no one, ever, can get out of here? It’s the madhouse from here, and that’s that. And no one, not even your crazy God, can do anything about it.” He sniggered at my discomfort and turned back to the wall. “A criminal. Very dangerous,” the druggy informed me.

My sister came back. “Nothing,” she admitted. “It’s up to the chief physician of the ward, who simply does not believe us and won’t sign a release. I’ll go on trying, if you can keep up Dad’s spirit. There isn’t any hope, though,” she sighed. I was only in the country for three weeks, and one was already gone, and my sister could not be away from her work much longer, either.

And so the days passed, the highlights being the chorister’s heart-warming singing, and the Psalms. “O Lord God of my salvation, I have cried day and night before thee. O let my prayer enter into thy presence: incline thine ear unto my calling. For my soul is full of troubles, and my life draweth nigh unto the grave. I am counted as one of them that go down into the pit; I am even as a man that has no strength. . . .”

Unbearable Hope

“ Now this is just not bearable anymore,” roared the weasely fellow. “I can’t stand it any longer! Why do I have to listen to that rot? You should not be allowed to read such drivel. Stop it! Go home!” and he put his head under his pillow and howled.

And the very next morning, upon our arrival, the nurse handed us the release, signed by the doctor.

“Grandpa, Grandpa, you are coming with us,” my ecstatic little chap shouted, and our sneering friend just stared, stunned and speechless. As our happy group filed out of the room I looked back, and he hung his head and turned to the wall when I caught his eyes. But what I had seen in them was not hatred, but wonder, and the glimmer of hope.

“I called upon the Lord in trouble; and the Lord heard me and set me free. The Lord is on my side; I will not fear: what can man do unto me?” Yes, I am content to be a loser.

Annegret Hunter recovered after homeschooling two boys and was pleased to discover she was still a Christian, a wife, and a bookbinder. Her husband Graeme is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor