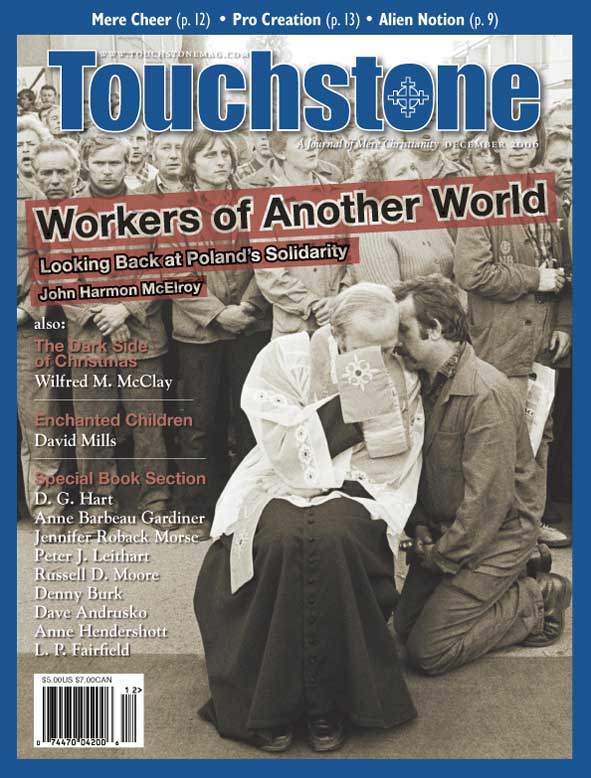

Feature

Enchanting Children

Training Up a Child Requires a Well-Formed Imagination

Some friends who live in a small house once found that half an hour or so into a party, everyone who had been scattered through the four downstairs rooms was jammed together in the living room. They could never figure out why, until the husband noticed that their Corgi, one of the sort bred to herd cattle by nipping at their heels, was gently herding everyone into the room by nudging the back of their legs.

The dog, he said, put on an extraordinary performance making people go (a) where they did not want to go, and (b) without their realizing it. This is how, I think, our culture forms our imaginations, and why children, who do not have the gifts to recognize the culture’s compelling Corgis, are so peculiarly vulnerable.

A Relentless World

We know, for example, that our cultural and media elite are aggressively pro-abortion. We recognize the culture of death in the National Organization for Women and New York Times editorials. It is easy to explain to our children that these people want babies to be killed when their mother chooses, and that this is wrong.

But our culture’s assumption against life—its anti-life imagination—runs much deeper than its ideological and political expressions and is much harder to see. The world propagates its imagination in ways so small we don’t even notice them, but so steadily and so relentlessly that it pushes us into agreement without our even noticing we are being moved.

Look at movie and television families. They always have only one or two children, or at most three, unless the family comes from the backwoods and is shown to be laughed at. The possibility of having another child is almost always a time of pain and struggle, even for married couples, inevitably so if the child is “unplanned.” The talented woman always regrets (at least sometimes) the life she gave up to care for her child. Daycare and public schooling are the parents’ default choices.

Sexual activity is completely disconnected from the creation of new life. Sex is a need and a right, but children a choice, and one that must remain unrestricted, even by conception.

The good life shown in commercials, articles in the travel section of the newspaper, in the lifestyle magazines, is always a life unrestrained by small children, indeed a life impossible with more than one or two children. The basic needs of children are so elaborated that children become effectively a life-style option for the affluent.

Families are, with a few exceptions, dysfunctional, and the families that function well are usually collections of affectionate individuals without established (and certainly not hierarchical) places in the family. Families are rarely religious and if they are, they are certainly dysfunctional.

Christianity teaches that love is necessarily fruitful, and that the act of sexual union within marriage is given us not only for emotional intimacy but for the creation of new souls. The union of bodies should produce bodies.

This seems natural to me, even instinctive. When the psalmist says, “As arrows are in the hand of a mighty man, so are children of the youth. Happy is the man that has his quiver full of them,” he is not rationalizing the needs of an agrarian society or a patriarchal social order, but saying only what every man and woman feel who in marriage have bet their happiness for the rest of their lives on each other.

But the incessant, inescapable message our culture’s dominant story-tellers give is: “If you want a child, and even if you’re married you may not, you will only want one, or maybe two, and only when he fits your schedule and budget, and does not reduce your quality of life too much, and only if you think the benefits outweigh the burdens.”

Imaginative Map

It is impossible to escape the effects, if you consume these stories, impossible not to begin, at least a little, to feel that they are true and to act and speak as if they are true. Ask any parent of, say, four or more children how many times he has been insulted by conservative Christians, and how personal these insults can be (“irresponsible” and “over-sexed” are among them). I remember as a father of one feeling shocked when I met a father of five, and I then thought of myself as a perfectly orthodox Christian.

At the best of times, our imaginations are under “the evil enchantment of worldliness,” as C. S. Lewis put it in “The Weight of Glory.” We are bewitched, even those of us who think of ourselves as countercultural.

And we, I should note, are one of the teachers of worldliness. We are sinners and inadequate icons for our children. Every father knows that his children will take much of their image of God the Father from him, and knows that they may mistake his softness or laziness in disciplining them for the Father’s mercy, or mistake his annoyance when disturbed for the Father’s wrath, or mistake his self-interested discipline for the Father’s justice. The problem is not only Hollywood, it is us.

Hence the need to form our children’s imaginations, to counter what the culture and our failings both teach them. By “imagination” I mean the faculty that controls what we, and especially children, think the world is like. It gives us the map by which we plot our course. It gives us our vision of the world about which our mind thinks and on which our will works. It tells us what feels normal, average, to be expected, what feelings should go with what actions.

To the extent a child has learned it in childhood, it changes his whole life, even when he thinks he has left his childhood behind. Even if he insists on losing his faith, it limits the sort of faith he will adopt instead. If he insists on sinning, it limits the sorts of sins he can commit with (so to speak) a clear conscience. It will determine how he rationalizes his sins.

It directs what charity he exercises. “[A]s we were driving through Sag Harbor just now,” wrote the lapsed Catholic writer Wilfrid Sheed,

. . . I saw three hopelessly fat, plain girls, who by the sound of it were also stupid, and I thought a certain pagan friend of mine might quite reasonably say, “Why do these fat, ugly people marry and procreate and produce such hideous children?” And I thought, No Catholic could ever say that. Nobody is altogether worthless to us.

There you have a man who, though he had lost his faith, was still governed in this matter by the Christian imagination he had gained in childhood. He saw the world—“imaged” the world—as a Christian, even after he rejected the practice of the Faith. He could not be a worldling.

Secularist Johnny

We tend to rely, I think, too much on knowledge. Even if Johnny has memorized the Baltimore Catechism or the Westminster Confession, or even hundreds of verses of Scripture, if his imagination has been formed by the wider, secular culture, he will respond to temptations as a secularist, not as a Christian.

He will know that fornication is wrong and that intercourse is a gift reserved for marriage, but he will feel that it is a recreational activity to be enjoyed with a willing partner by someone of sufficient maturity to use “protection”—though the Christian teaching may affect him enough that he feels it requires some degree of “commitment.” When he brings himself to temptation, his feelings are more likely to move him than his thoughts, and of course once he falls, his thoughts will start to change to fit his feelings.

He will not feel fornication to be a very bad sin nor a personal danger. He will not feel purity a precious possession to be protected. He will not feel that the challenge of restraint is a challenge worth meeting. He will not feel that certain alternative forms of the sexual act are really sexual, which is to say, even if he reserves intercourse for marriage, he will indulge in these other forms with no idea that he is still fornicating. (Professors at Christian colleges have told me that this is true of many of their students.)

I stress this because I think that many Christian parents are more modern than they realize, especially in assuming that knowledge of itself makes us good. Think, to take the crassest example, of those many Christian parents of high-school students who drive their children to pursue the elite college, assuming that their spiritual life will take care of itself.

As St. James pointed out, even the devils believe, in the sense that they know what the reality is (James 2:19). But they cannot imagine that the reality is good. They may know of God the Father, but to them such Fatherhood feels like domination and oppression, because their imaginations are so completely corrupted. They do not hear “Thus says the Lord” as “Here is the antidote for the poison that is killing you,” but as “Down, vermin slaves.” Think of Uncle Andrew in The Magician’s Nephew, who hears Aslan’s kind words only as a threatening growl.

Normal-Feeling Goodness

What we want our children to imagine depends upon what we want our children to be. As Christians, we want them not just to learn to understand and analyze rightly, but to react rightly because they see the world rightly. We want our children to know by instinct or intuition what is the right answer, the right action, the right attitude.

Revulsion is a much better protection from the force of the passions than an intellectual understanding by itself. To feel “This is yucky” is not a final protection from sin, but it is better than thinking “This is wrong” but feeling “This is okay.” Lust offers the paradigmatic case (examples come quickly to mind), but this is true of pride, gluttony, envy, and all the rest, even sloth.

To put it another way, we want to raise kings, children at least somewhat worthy of the status of sons of God they have received through our Lord’s death on the Cross. We do not want the average, the mean, the mediocre. We want the elite.

Children with a special calling must be trained in a special way. They must be set apart. More must be asked of them than we would ask of other children. This is not easy to do. We are giving them a privilege that will seem to them like a burden.

One way to set them apart is to try to form their imaginations, to give them an alternative to the worldly lessons even the sheltered child absorbs as if from the air, by immersing them in books that express the Christian understanding of the world.

Some children seem to be impervious to even the most obvious lessons, but in general, a child who spends time in a good writer’s world will find his imagination formed by it, at least a little. A good story will not make him good, but it should help him understand goodness a little better and make doing good a little easier by making it feel more normal. It will teach him that the world is this kind of place and not that kind.

At the very least, the time the child spends in the world of the good stories is time he has not spent in the world of the bad stories. The good this does is not, these days, to be dismissed.

Stealing Past Dragons

Let me use (for obvious reasons) C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien as examples. C. S. Lewis wrote that as a writer he began with a picture that he wanted to tell a story about, but as a man, he wanted his stories to do some good. In particular, to make Christianity believable to modern people trained to reject it. He saw, he wrote in an essay titled “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Best Say What’s to Be Said,”

how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralyzed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical.

He had an answer: “supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday School associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could not one steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.”

The Narnia Chronicles were his major work of tiptoeing. Aslan says to the children at the end of The Voyage of the “Dawn Treader”: “The very reason you were brought to Narnia is that by knowing me for a little here you may know me better there.”

For what it is worth, I don’t agree with this. I don’t think translating stories we believe happened into other stories we’ve made up helps us understand the original better. Allegory may work as illustration but not as illumination. I think that a story in which the Christian mind and imagination are assumed may make the world in which the original stories happened more plausible to us, and therefore may help us see the originals “in their real potency.” (In other words, I side with Tolkien in their dispute.)

In The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Aslan is a bit too much the illustrated Bible story. The fact that a lion in a story gives up his life and then rises from the dead does not make the gospel stories more believable or compelling. At least I did not find it helpful as a minimally Christian child.

Better Stories

The later stories are better at this, because Lewis began incorporating the messages more deeply into the stories themselves. In The Silver Chair, for example, he prepares the reader for the anti-religious theory of “projection.” This is the idea that all religious doctrines and experiences are simply things we would like to believe and things we would like to feel given the authority of a God who does not exist. It is still, in various forms, the standard secular explanation for religion, the sort of thing your children might hear taught as a truism in sociology or psychology 101.

At the climax of the story, a witch has trapped the four heroes in her underground kingdom and tries to convince them that there is no other world. One of them argues that he has seen the sun and another explains to her that the sun is like a lamp hanging in the sky, but they cannot explain it to her except through metaphors. She replies that since they cannot tell her what the sun is, “Your sun is a dream, and there is nothing in the dream that was not copied from the lamp.”

A third says “There’s Aslan,” and she replies again:

I see that we should do no better with your lion, as you call it, than we did with your sun. You have seen lamps, and so you imagined a bigger and better lamp and called it the sun. You’ve seen cats, and now you want a bigger and better cat, and it’s to be called a lion. Well, ’tis a pretty make-believe . . . look how you can put nothing into your make-believe without copying it from the real world, this world of mine, which is the only world.

One of them eventually breaks the enchantment by stamping bare-footed on a fire, which brings them back to reality.

Lewis has put into the story an idea his readers will hear seriously expressed, and he must have hoped that having seen in the story how seductive but wrong the idea was in Narnia, they will know how seductive and wrong it is in the classroom at Voltaire State University, or at least feel that there is something more to be said than their smugly agnostic professor is saying. They may not remember the story, but they will have in their imaginations the understanding that some truths are difficult to communicate to the wicked and ignorant, but are true even when you are defeated in debate.

Lewis teaches what I think is an even subtler lesson in the last book of the series, The Last Battle, that sin corrupts and destroys our vision of the good, a lesson we have peculiar trouble in accepting. (It is the same lesson he taught through Uncle Andrew.) Aslan is said to have returned to Narnia after many years away, but he is reported to be killing the woodnymphs and selling animals into slavery. This, the reader knows, is not the real Aslan.

Nevertheless, the King and his closest friend, who are Aslan’s good and faithful followers, do not realize that the new Aslan is a fake. They cannot see this because they sin, and in stages, beginning with a perfectly understandable and apparently minor sin. At first, they act in anger, and so cannot be sure of the good, and at this point wonder if the fake Aslan is the true one. Then they murder two unarmed enemy soldiers and so believe in the fake one. This happens in different ways to other creatures.

They all forget the paradox, known in Narnia as a kind of creed, that Aslan is not a tame lion, “but he’s good.” They remember only the first part, which becomes a reason to believe that he may do evil and if he does evil they must submit to it and must do it if he orders.

Lewis has put into this story a lesson in the nature of faith, and in particular the effect of sin upon our vision. It is a subtle lesson, but still one the child may absorb, and may learn, a little, to distrust beliefs that contradict what he knew because he senses that he may have made himself unfit to see the truth.

Providential World

Unlike Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien thought that the story did good simply by being a good story, and that the writer should not intentionally put into his stories the sort of meaning Lewis put into his. You cannot find in The Lord of the Rings the sort of Aslan equals Jesus analogy or allegory you find in the Narnia Chronicles (which Tolkien disliked).

Tolkien thought that a good story created a “secondary world” that had to reflect the laws and nature of the “primary world,” the world as we know it really is. “Creative Fantasy is founded upon the hard recognition that things are so in the world as it appears under the sun; on a recognition of fact,” he wrote. These facts include the facts of the moral order and the supernatural world.

The world as it appears under the sun is a world loved and governed by God, and The Lord of the Rings is among other things a study in Providence. Though no god of any sort is ever mentioned in the story, the world has a moral law, recognized as eternal and binding, obeying which brings blessing.

That law includes the proper burial of the dead. At the end of the first book, three of the heroes, Aragorn, Gimli, and Legolas find that their friends have been taken by enemies (a band of creatures called Orcs) and their companion Boromir dying. They do not know if the Orcs have taken the main hero Frodo and the Ring he carries.

If they have, and Aragorn and his companions do not catch and rescue him, the world is doomed. Even if the Orcs do not have him, they have his friends, from whom they will learn Frodo’s plans and catch him anyway, and the world is doomed.

To obey the moral laws of their world, they must bury their fallen comrade, but if they do, they will lose several hours before they can chase the Orcs, meaning that they will almost certainly get away. But Legolas says, “First we must tend the fallen. We cannot leave him lying like carrion among these foul Orcs,” and Gimli agrees. And they do so, when doing so seems the most insane, irresponsible, lunatic thing they could have done. But they did it because it was the right thing to do.

And—here is Tolkien’s genius in plotting—because they do spend several hours in burying their comrade Boromir, they never catch up with the Orcs who captured their friends, yet this works to the salvation of their world. It does this in several ways, but the most obvious is that the captured hobbits escape and meet a powerful character who would not otherwise have entered the story at all, which leads to the destruction of one of their two greatest enemies and then the relief of the siege of a crucial fortress about to fall and (as it happens) the rescue of Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli, who are crucial to their cause’s success later.

The child who has been formed by living in Tolkien’s world should understand how Providence works, especially how doing the right thing even when it seems the suicidally wrong thing can be taken up into a greater plan and contribute to a good he could not achieve otherwise. He may not see the effect I’ve described (most scholarly writers on Tolkien don’t), but he should begin to feel, among many other good feelings, how obedience to the moral law even when it seems foolish and impractical works to accomplishing the good, and how disobedience brings destruction.

Nurturing Imaginations

I said before that Christian parents are trying to raise kings, children at least a little bit worthier than they are of the status of sons of God they have received through our Lord’s death on the Cross. I got the idea from my friend Steven Hutchens, who once wrote about television that “I feel something like King Lemuel’s mother warning him against strong drink: she never says that it is an evil in itself but that it is ‘not for kings’.”

The reference is to Proverbs 31. There are many things, good enough in themselves, or at least neutral, we ought to pass up if we are to live as kings.

The goal is certainly a compelling one, once you see it. It is a good thing, to be a king, because you are called to do things only you can do and these things matter. I have often thought that the Prince of Wales would not be so odd if being the King of England meant anything.

But to raise kings, Christian parents have to accept the fact that they are not only going to go against a powerful cultural stream, but that they will be making their children go against it too. They will be trying to make their children the very last thing a child wants to be: an eccentric. The children will scream. I can show you tapes.

Just to restrict and direct their use of television (as they must do) sets them apart from the peers, especially if (as we chose to do when our first was very small) you do not watch television at all. You are removing from them an occupation that gives pleasure without effort and is at least slightly addictive. You are stripping them of the main source of conversation and cultural references among their friends and classmates.

You might as well dress them in Victorian costume. The eternal value of reading the Narnia Chronicles instead of watching Survivor or 24 or Lost will not be obvious to them.

Making your child an eccentric is very hard to do. I have no idea how to do it well, other than sheer will and the attempt to live your own life to even higher standards, trying to make it clear to your children that you are not asking of them anything you do not ask of yourself, and that you do it from love of Jesus and the nobility he offers.

Parents who seek to help form the kingly imagination will read to their children the Christian and other classics, starting at a very early age and continuing as long as possible. I love reading aloud, so this has always been a pleasure for me, though I realize it may not be so for others. We found it very hard, even with just four children and a short commute, and without the competition of television, to order our evenings to read to all of them.

But it is worth the effort. Hearing his father or mother read a good story forces the child to hear and begin to imagine stories he would not necessarily read himself, and it gives you another time to talk with him about the deeper things, without being overtly religious in the way that puts off so many children.

The time may, as I found with our first three, encourage them to bring up more personal questions they felt shy of asking out of the blue, which they usually asked well into the reading time. And they see their parents enjoying a story and reading it seriously, for what they can learn from it. To put it another way, they see gratitude for God’s gifts and learn gratitude themselves.

Chief among the classics to be read, of course, are the Scriptures, read as if they were classic stories, without their stained-glass and Sunday school associations. You would read them, for example, without drawing simple dogmatic lessons, as if the stories were primarily illustrations for ideas you’ve gotten from the Catechism. You would also read them as if they were written by one author, connecting “what he says here” with “what he says there.”

And you will read as if these were not just good stories, but our family’s story, as if when we said “Abraham” we were saying “great-grandpa” and when we said “St. Paul” we were saying “your saintly uncle Paul, the genius.” This is harder to do, and is conveyed mostly in an attitude of possession and reverence, of the sort you have for your greatest and most interesting of ancestors.

Good stories read seriously and with enjoyment will help form a child’s imagination, and give it a shape it will never entirely lose, no matter what the child does when he grows older. But we would be foolish to rely on stories to do more than stories can. Wise Christian parents will immerse themselves and their children ever more deeply in the life of the Church, whose worship and teaching and charity and fellowship will be the most profound creator of the Christian imagination.

There they should meet Jesus. The world in which the child knows that Jesus is present is a world he will always live by, even in reaction and even when he convinces himself that it is an illusion. The well-formed imagination is a gift that keeps on giving.

The insight into The Silver Chair is taken from Stephen Smith’s “Awakening from the Enchantment of Worldliness” in The Pilgrim’s Guide; a longer exposition of Providence in The Lord of the Rings can be found in the author’s “The Writer of Our Story” in the January/February 2002 issue of Touchstone.

His Dark Witness

A parent is safer sharing with his children consciously Christian writers, but not wise to share only them, for other writers may help form a Christian imagination, if read with discretion and guidance.

Though the English writer Philip Pullman’s best-selling and wildly praised trilogy His Dark Materials is an openly anti-Christian book, even it can contribute something to the forming of a child’s Christian imagination—if (and this is important) read with someone who can lead him to understand it.

It is a retelling of the story of the Fall of Man in which the Fall is a very good thing, not least because it includes the literal death of God. The book, he has explained, “depicts the Temptation and Fall not as the source of all woe and misery—but as the beginning of true human freedom, something to be celebrated, not lamented. And the Tempter is not an evil being like Satan, prompted by malice and envy, but a figure who might stand for wisdom.”

In the books—The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass—Pullman makes a very big point of saying that death is a good thing because though we disappear completely, our atoms will be merged with the rest of the “living universe.” Several characters wax lyrical over this.

But he cannot let his heroes die the death he praises. When one dies in battle, “the last little scrap of consciousness” that was him “conscious only of his movement upward . . . passed through the heavy clouds and came out under the brilliant stars, where the atoms of his beloved . . . Hester, were waiting for him.”

Notice that the dissolution into atoms that Pullman can offer as a satisfactory myth when he is talking about people in the abstract, he cannot accept when he is talking about one of the characters the reader, and I presume he himself, cares about. Then he must grant the dead man not only some sort of personal existence after death, but a reuniting with those he has lost.

He must supply something for which there is no room in his philosophy or even in his story itself. He has to write something of the Christian story into his anti-Christian story.

I mention Pullman because he is a writer you ought to know about and because he illustrates how even intentionally anti-Christian stories can help form a Christian imagination, if read with discernment. (And to be fair, there is much that is quite good in the story, despite Pullman’s atheism.)

I would not give a child His Dark Materials to read by himself, but I might read it to an older child and talk about it with him. (Every time I have spoken on Pullman I’ve found that almost all the children have read him, but their parents have rarely heard of him.) It can help form a Christian imagination with some help from the Christian parent, if mainly by showing the nature of the alternative.

— David Mills

Drug Stories

Any art form can be used well for the glory of God and the edification of his people, but movies, television, and video games rarely are. They tend, all three, to be a drug, a way of pacifying the mind and feelings, but more importantly a way that bad ideas and tempting images take a place in your mind while it is drugged and pacified.

They are also much less effective in forming an active and discerning imagination. There is a radical difference between making the pictures in your mind and letting in pictures someone else is providing. You get stronger from running uphill, not from riding downhill in the car.

I think the Christian should think about these media as someone who has alcoholics in the family should think about wine and beer. They are good, and gifts from God, but to be enjoyed in moderation and with a careful watch for any sign that they are becoming addictions. We must assume that we are inclined to abuse them and to abuse them without realizing it.

And some works the Christian must avoid at all costs. There are things you should not see. And the things you should not see may be relatively minor. I have long thought that the sweater slipping off the shoulder of a beautiful girl in a PG movie may be worse for most males than the same girl topless in an R movie, precisely because it is suggestive, even though it is technically much more modest.

I am not suggesting that you skip PG movies and watch R movies instead, but that you be alert for temptations even in things the world has labeled innocent. The world’s standards are entirely technical—what rude words are said, what parts of the body are shown and for how long—but the Christian’s must be moral.

And there are things you should not do. We become what we enact. Violent video games require you to imaginatively enter their world and become someone who kills, and kills for fun. You kill people you may know at one level of your mind are colors on a screen, but your mind at another level sees them as people. People playing these games are training themselves to take human life carelessly.

Stewarding the Eyes

Christian parents must control the visual media in the home, to practice a modern version of what was once called the stewardship of the eyes. Otherwise the media will control the home. Conversations that would evolve naturally will be cut short, or never started, for example, because a television program that must be watched is starting soon.

We do not watch television at all, and this I earnestly recommend—you would not believe how much more tranquil and relaxed is a home without television, and how creative children forced to their own devices can be.

If giving it up seems too radical a change, try first fasting from television. Give it up for Lent, for example, and then look at the difference its absence makes, and how easily it is replaced.

This is one of the actions that will most make your children feel eccentric. We told ours to tell their friends that their parents were artsy types, so that not watching television fell into the same category as vegetarianism and other odd but somewhat acceptable lifestyles. This was only partly effective.

Christian parents need also to watch movies with their children and try to show them what the movie is doing. Our eldest two children were fairly sophisticated for their ages, but I was often (and am still) surprised by how much they do not know and how they can be taken in by what seems to me the most blatant propaganda.

If you know something about movies, you will be able to point out how the director is using the tools of the trade to make his point. You can talk about camera angles and the like.

But even if you don’t, you can help the child engage the movie and begin to discern what it is saying, by asking the basic questions like: Is what the movie is saying good? Bad? How does it do that? Is that character believable? Do you think the movie was fair to such people? Does the director believe in God? Why or why not? And so on.

And you will radically limit the time your children play video games (if they do), even the non-violent ones, like the racing games. Though some of them are in theory educational, I suspect most children do not learn much from them. Video games are for them pure diversion, pure excitement, which is something not for kings, at least in large constant doses.

—David Mills

David Mills has been editor of Touchstone and executive editor of First Things.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on imagination from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor