Feature

Our Faith Observed

The Three-Fold Cord of Imagination, Reason & Will in C. S. Lewis

So I called over my shoulder to Billy, the car mechanic, “Are my rear blinkers working?” And he replied, “Yes, no, yes, no, yes, no, yes.” Which made me realize that there was indeed a loose connection, not in the electrical circuits of my car, but in Billy’s mental apparatus—more particularly, in his imagination.

Billy had sufficient imagination to find some meaning in my blinkers, but not enough imagination to find full meaning. For him, the fact that my lights were on meant that they were working and the fact that they were off meant they had stopped working.

Now that is better than nothing: It shows that he knows the basic meaning of electrical circuits. But it is not enough: He needs to exercise what C. S. Lewis called “the organ of meaning”—his imagination—a little more fully, to see that the occasional absence of light does not mean the circuit is not working, it means that the circuit is working as a blinker.

Imagination & Nonsense

What would you say is the opposite of meaning? Error? According to Lewis, the opposite of meaning is not error, but nonsense. Things must rise up out of the swamp of nonsense into the light of meaning if the imagination is to get any handle on them. Only then can we begin to judge whether their meanings are true or false. Meaning is “the antecedent condition of both truth and falsehood.”

Not every flashing light on a car is meaningful. Sometimes there really are loose connections, whose occasional bursts of luminosity, flickering on and off in no particular rhythm, we should best describe as nonsensical: The connections are arbitrary, random, meaningless. If the connections were regular or patterned, however, we should be inclined to conclude that they were significant, meaningful.

But what kind of meaning would they have? A true meaning, showing that the driver was about to make a turning? Or a false meaning, showing that the driver had forgotten to cancel the lever? It is reason, in Lewis’s view, that judges between meanings, helping us to differentiate those meanings that are true and illuminating from those that are false and deceptive. If the driver passes several junctions without making a turn, we reason that the flashing blinker is a misleading signal. Reason is, for Lewis, “the natural organ of truth,” which operates in consort with imagination, “the organ of meaning.”

That is enough about imagination. We will come back to it in a minute, but now let us turn to Lewis’s understanding of Christian faith and look at the role played by imagination in his own journey towards acceptance of Christianity.

What Doctrines Mean

You may well know the famous account of Lewis’s long nighttime conversation with two of his good friends, J. R. R. Tolkien and Hugo Dyson, on the subject of Christianity and myth. This took place at Lewis’s college in Oxford and was described by Lewis as the immediate human cause of his conversion. Lewis’s whole problem with Christianity, at that stage, was in knowing what Christian doctrines meant. Tolkien and Dyson showed him that Christian doctrines are not the main thing about Christianity.

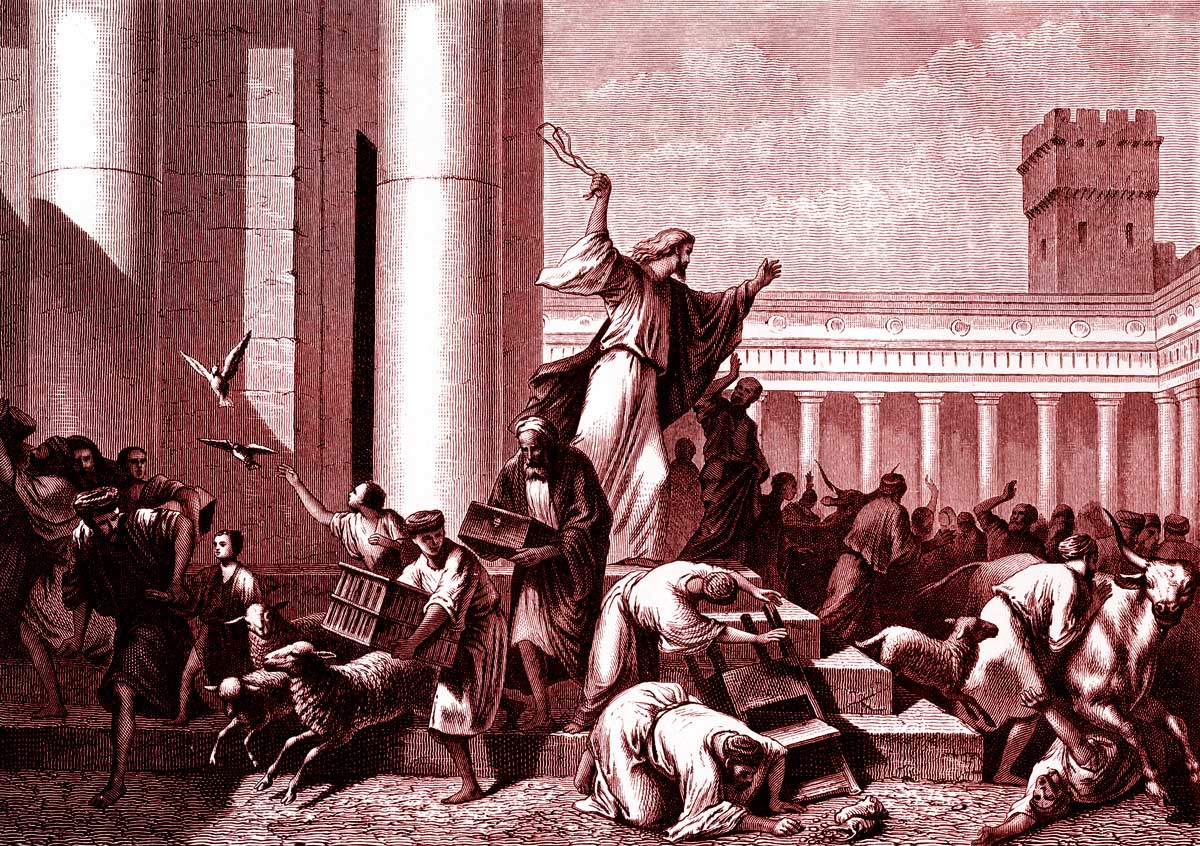

Doctrines are translations into our concepts and ideas of that which God has already expressed in “a language more adequate: namely the actual incarnation, crucifixion and resurrection” of Christ. Of course, it is not wrong, it is very beneficial, to translate the language of incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection into doctrines—theological doctrines of redemption, sanctification, justification, expiation, propitiation, and so forth—but the doctrines are secondary.

The primary language is the lived language, the real, historical, visible, tangible language of an actual person being born, dying, living again—and still living today. And when Lewis realized this, he began to get a handle on what Christianity really meant, because he was already fascinated—he had been fascinated from childhood—by stories of dying and rising gods. Throughout world literature there are myths of characters who die and go down into the underworld and whose death achieves or reveals something back here on earth: new life in the crops, for instance, or sunrise, or the coming of spring. Lewis had always found these pagan stories—he mentions those of Adonis, Bacchus, and Balder among others—to be profound and suggestive of meanings beyond his grasp.

He couldn’t say in cold prose exactly what they meant, but these stories he thought were fruitful in their own terms. They were myths that had to be accepted as saying something in their own way, not treated as allegories and translated into something less, something secondary, mere doctrines (useful though doctrines are in their place).

When Lewis realized that Christianity could be approached in the same way he approached pagan myths, it was a huge breakthrough for him. At an imaginative level, pagan myths of dying and rising gods did much to enable Lewis to embrace the story of Christ. Christianity, he now saw, was a “true myth.” Pagan myths were “men’s myths.” In them, God expressed himself in an unfocused way through the images that human imaginations used to tell stories about the world.

But Christianity was “God’s myth,” God expressing himself through the real, historical life of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ. That there were certain similarities between pagan myths and the true myth did not lead Lewis to conclude, “So much the worse for Christianity”; it led him to conclude, “So much the better for Paganism.” Paganism had a good deal of meaning that was fulfilled and summed up in Christ.

In a sense, Lewis had found in pagan myths what Christ himself had said could be found in the Old Testament story of Jonah. You remember how Jesus told the Pharisees: “No sign will be given this generation except the sign of Jonah: for as Jonah was in the belly of the great fish for three days and nights, so the Son of Man will be in the heart of the earth for three days and nights.” Jonah’s descent and re-ascent are a meaningful prefiguration of Christ’s own death and resurrection. Lewis found a similar prefiguration of Christ in the pagan myths.

Christianity Without Meaning

“So what?” you may ask. “We now know that true myth, the Christ event. What does it matter to us that there are these other somewhat similar stories?”

To ask such a question neglects the vital importance of meaning, of imaginative response. For Christianity is not only true, it is also meaningful. “Of course,” you say, “to be true, Christianity has to be meaningful, for meaning is the antecedent condition of truth!” Yes, but go with me here. Suppose truth and meaning could be separated. Which do you find yourself automatically regarding as the more important: truth or meaningfulness? It’s an interesting thought experiment to conduct on yourself.

When addressing mostly conservative Christians, I wouldn’t expect to find anyone prepared to describe Christianity as untrue, but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if there were many for whom Christianity does not really mean very much. For some Christians, the light of Christianity’s meaning will flash on and off in a pretty random, arbitrary way, so that it fitfully suggests all kinds of odd meanings.

“Christianity? Oh yes—something my mom and dad do.” “Christianity? Oh yes—isn’t it something to do with Republican politics?” “Christianity? Oh yes—something tiresome about not sleeping with my girlfriend.” These connections are so fitful and incomplete that Christianity, if you persist with it, will become effectively meaningless, even while you of course continue to regard it as “true.”

For other Christians, the light of meaningfulness will flash regularly and rhythmically, but still effectively without meaning. You know that Christianity is primarily about Christ, living, dying, and rising—and living still today. You will have been told this so often that you have become inoculated against its real significance. For you, Christianity is like an uncancelled blinker. There it is, flashing away, regular as clockwork, doing its thing, but the driver has no intention of turning.

This is a most dangerous situation to be in, and it is one of the real dangers of a Christian upbringing and a Christian education. For although a Christian upbringing and a Christian education are good things and better than the alternative, it has to be remembered that each spiritual advance carries with it its own spiritual risk: The higher you climb, the further you will fall if you fall.

This was why Lewis sometimes spoke out against what he called “wearisomely explicit pietism.” Or, as he put it elsewhere, “There is nothing that callouses the hands so effectively as a constant dealing with the outsides of holy things.” One needs to get to the insides, to the pulsing blood and the vital juices, the living organ of meaning, not just the skin of truth, indispensable though that skin is to healthy Christian living.

Lewis once wrote that the mythical element in Christianity is the really nourishing element in the whole concern. He even goes so far as to say that a man who thought Christianity untrue, yet constantly fed on its imaginative meaning, might be more spiritually alive than someone who accepted Christianity as “true” but never thought much about it.

The organ of meaning and the organ of reason are, of course, both necessary to a full Christian life; but an excessive emphasis on the truth of Christianity, as if it were simply a matter of intellectual or rational assent, at the expense of Christianity’s meaningfulness, at deeper, imaginative levels— that may be damaging. Truth is always about something, Lewis wrote; but meaningfulness is that about which truth is.

Reconciling Maid & Mother

At this point I want to offer a poem on the subject of imagination and reason that Lewis wrote around the time of his Christian conversion:

Set on the soul’s acropolis the reason stands

A virgin, arm’d, commercing with celestial light,

And he who sins against her has defiled his own

Virginity: no cleansing makes his garment white;

So clear is reason. But how dark, imagining,

Warm, dark, obscure and infinite, daughter of Night:

Dark is her brow, the beauty of her eyes with sleep

Is loaded, and her pains are long, and her delight.

Tempt not Athene. Wound not in her fertile pains

Demeter, nor rebel against her mother-right.

Oh who will reconcile in me both maid and mother,

Who make in me a concord of the depth and height?

Who make imagination’s dim exploring touch

Ever report the same as intellectual sight?

Then could I truly say, and not deceive,

Then wholly, say, that I BELIEVE.

The most important line, I think, in this poem is the question: “Oh who will reconcile in me both maid and mother?” In asking that question, Lewis is presenting himself as a candidate for the attention of the Holy Spirit. He is presenting himself as Mary, who was both virginal and fertile, both maid and mother. Remember what the angel said to Mary: “The Holy Spirit will come upon you and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.” Lewis, by asking for his fertile imagination and his pure reason to be united—reconciled—is effectively asking the Holy Spirit to overshadow him.

And often in Lewis’s discussions of faith it is Mary’s example that he holds up for his readers to emulate. “We are all feminine in relation to [God],” he writes in That Hideous Strength. “Our highest activity” is female responsiveness (in The Problem of Pain). That is why a female character, Lucy, sees Aslan more often than any other character in the Chronicles of Narnia. For if mankind is to be saved, God must take the initiative. He is the bridegroom; the Church is the bride.

Lewis sometimes pictured the human person as consisting of three concentric rings: The outer ring is imagination; the middle ring is reason; the innermost ring is the will. And the human will is powerless to save itself, to turn away from self by its own unaided efforts. The most it can say, echoing Mary, is, “Be it unto me according to thy word.” In saying this, the will abandons the role of speaker and adopts the role of listener. It steps down from the podium and into the audience. At that point, the human will can hear God’s word; and to hear is to obey. With obedience, faith has come alive.

So, when it comes to the acquisition of faith, we must recognize our role as patient, God’s role as agent. Only then can we conceive faith. And this is humbling, because we like to think we are in charge and calling the shots. But if we know God at all, we know that he is calling the shots. Lewis never forgot this.

In one of the Narnia Chronicles, Edmund is asked if he knows Aslan, and Edmund replies, “Well, he knows me.” In another work, Lewis makes the bold statement that “how we think of God is of no importance”— no importance!—“except insofar as it is related to how God thinks of us.” In yet another place, he reflects on the frantically comic picture of the fly sitting and deciding what it is going to make of the elephant—that’s in an essay entitled “What Are We to Make of Jesus Christ?”

The Three Rings

Imagination, reason, will. All three rings need to be simultaneously purified and fertilized by the loving action of the Holy Spirit as he brings Christ to birth in us. Most Christians rationally assent to the truth of Christianity: Reason, the middle ring, is converted. But without imagination on the one side feeding on the meaning of that which has been rationally assented to, and without will on the other side actually choosing to do something about it, reason’s power of maintaining assent will gradually wither. If imagination and will say “No,” there’s no long-term future for reason’s “Yes.”

Remember the first chapter of 2 Corinthians? “For the Son of God, Jesus Christ . . . is not ‘Yes’ and ‘No,’ but in him it has always been ‘Yes.’ For no matter how many promises God has made, they are ‘Yes’ in Christ.” And because those promises are Yes in Christ, they can be Yes in us too—in our imagination, in our reason, and in our will.

“Hey, Billy, is my faith working?”

“Yes! Yes! Yes!”

“Our Faith Observed” is adapted from an address he gave in

the Wheaton College

chapel in September 2005, during a conference on C. S.

Lewis.

C. S. Lewis’s poem reprinted from Poems by C. S. Lewis, copyright ” C. S. Lewis Pte. Ltd. 1964. Reprinted by permission of The C. S. Lewis Company Ltd, Poole, Dorset, and Harcourt, Inc., Orlando, Florida.

Michael Ward is Senior Research Fellow, Blackfriars Hall, University of Oxford, and Professor of Apologetics at Houston Baptist University. He is the coeditor of The Cambridge Companion to C. S. Lewis (2010).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor