Feature

Over Our Dead Bodies

Men Who Are Willing to Lay Down Their Lives Are Truly Indispensable

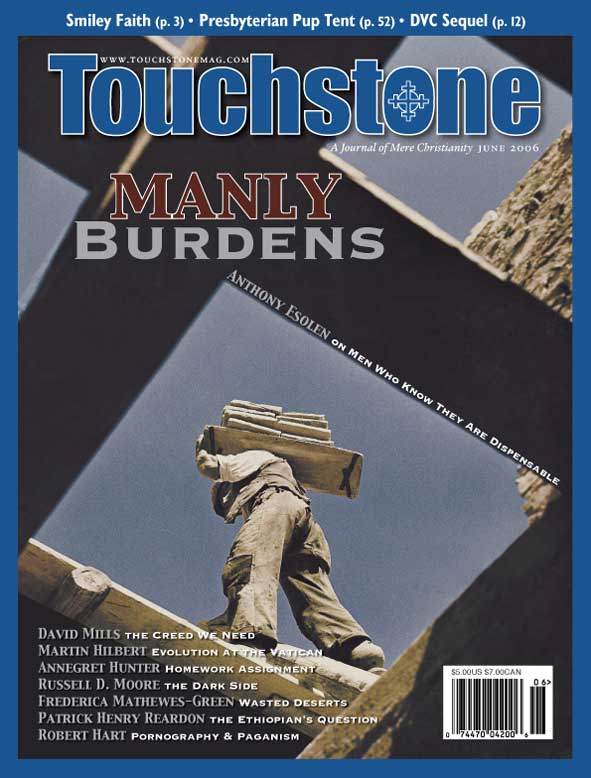

When the old slate quarries of the Pennsylvania town ceased operation, the land was sold to an enterprising fellow who leveled the heaps of refuse and cleared dozens of acres for junking cars. That man’s a millionaire now, and does necessary work, but he has not been able to alter the quarries entirely.

On his property remain three holes, each of them well over an acre in breadth and from a hundred to two hundred feet deep, now shining as lakes of cold clear water. They are banked by screes of jagged slate that will cut a bare foot as quickly as shards of glass, as I have found by experience. But sometimes it is not a bank, either, but a veritable wall cut vertically in the rock, with the clean corrugations of the quarrying saws still visible.

Wrested Slate

Water was an important part of the slater’s day. You had to recirculate water as coolant in the works of diamond-grit saws, lest in a few moments the heat generated by the friction of blade-rock against quarry-rock fuse the machine’s innards. The -quarry’s own gut had to be pumped continually, lest the breached water table fill the cavity. And human bellies, too, have their needs. A workman might sweat fifteen pounds of water on a day of normal heat. They replenished it, usually in a form to stir up conviviality or fighting or both; and those, too, are not the least of the calls of the man’s life.

For all that it had to be wrested from the mountains by daring and force, the slate was put to delicate use: blackboards for schools, tables for elegant dining rooms (and for smoky billiard halls), and shingles for anyone who could afford better than wooden shakes and tarpaper. To my eye, there is no finer roofing than slate, sometimes glossy black but oftener a sheeny silvery-gray with irregular washes of light iridescence.

The shingles are cut square, oblong, or scalloped, to cover the gables and turrets of Victorian houses. And when the sun breaks out upon a slate roof after a storm, the tiles glisten like jewel-work. Delicately beautiful are they, yet stalwart and stubborn. Some slate slabs an inch thick can support the weight of two men; and slate shingles can last over a century without crumbling or falling.

That town was literally sawn out of the hills by sturdy Welshmen. Now its Welsh character and its sturdiness are hardly memories. What else, when “safety” is extolled as the summum bonum, and when we are all encouraged to look upon the globe as our dreary universal suburb, rather than see in our own small town a peculiar and precious glint of the universe? Welsh boys no longer pick fights with Italian boys from the Catholic town above. Do not attribute to forbearance what may more plausibly be attributed to apathy or despair. They don’t fight, because there is nothing to fight for.

We Must Not Fall

Yet maybe a vein of the old virtus remains beneath, sustaining the flitting life above it, but unseen and unknown. For when the junkman bought that land, the town required him to render it “safe” by putting a chain-link fence and barbed wire around the most spectacular of the lakes. We must not fall for or into anything: That is the first rule of the nannied life. But the local boys have dutifully trodden the fence down in several places, and wise policemen have looked the other way.

If you walk up there, then, and trespass over the straggling barbed wire (as I have), you will be struck by a sudden vista of astonishing beauty. On two sides you will have to scramble over jumbled slabs of slate, from a few pounds to many tons, steeply concluding in a lake as broad as a park. Its sides facing you will be banked by walls, etched and grooved by man’s tools, tufted with grass and birch at the top and in odd dirt-catching crevices, rising to a height of 115 feet above the water.

But the trespassers are boys, so naturally there’s more. I don’t mean smashed-glass evidence of parties or other debaucheries, though that is there. Initials, names, some insults, dates, and other feints at immortality are painted on that wall, at all heights. The only way any kid could do it is by hitching himself to a rope, secured by his buddies at the top. Some insults it takes a team to deliver.

Nor is it a small matter to fall into the water from such a height. Fall with a leg cocked and it may snap like a matchstick. Fall aslant and you may break your back or your neck and drown before anybody can get to you—even if there were an easy shore for you to be conveyed to, as there is not.

One young man told me that jumping off the cliff was the most dangerous thing he had ever done. He wore sneakers, he said, to give his feet weight and help him point the toes downwards. It didn’t help: the force of the air lifted them against his strength, and when he hit the water his legs felt as if they had been jammed upwards, like a cartoon character’s, into his trunk. He leapt twice, though.

So down you go to paint your initials, to boast about your football team, to decry the perversion of a particular enemy, or to display perduring affection for a girl whose name you will have forgotten long before your hair is gray. But you see to it that the cliff remembers. And there on that same wall, twenty feet from the top, some patriotic lad has painted, in block letters eight feet high, with stars and stripes in red, white and blue, the words UNITED WE STAND.

Manhood’s Risk

In this place, risk and manhood are to be glimpsed in an instant, with beauty and folly, and pride and love, hard to extricate the one from the other. It is a strange and bold witness of life. Like life, it is heartily unsafe. It brings no therapy, no anodyne; it is not the dose of nepenthe that Helen of Troy, the essential matriarch, slips her semivirile husband; it is not the lotus; it is not what we whimsically call Higher Education.

Men cut the rock, and the rock cuts back. We men who have neither been born eunuchs nor made ourselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven, but who have allowed others to make eunuchs of themselves and of us, all for a watercolor impression of peace, a safe life of Monet purple, with even erotic love blurred into the bland, as we pretend to courage while rutting in padded cells with helmets and shin guards and other soft and slack prophylactics of the soul—we nannied men could not have carved this place.

Yet a memory of what men could and did create lingers: United We Stand. Brave fellow, he who painted that. Were I his father and had I learned of the stunt, I would exercise my prerogative and administer to his backside another sort of tattooing. But I would be proud, too.

A husband is the head of his wife, says Paul, “even as Christ loved the church, and gave himself for it; that he might sanctify and cleanse it with the washing of water by the word, that he might present it to himself as a glorious church, not having spot, or wrinkle, or any such thing; but that it should be holy and without blemish.” Ah, the hard sayings of Christ and his apostles!

Individualists may balk at “Inasmuch as ye have done it unto the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me,” and that says little about Christ and a lot about the pinchedness of individualists. Capitalists squirm when they hear that the rich young man “went away grieved: for he had great possessions,” and that says little about Christ and a lot about the dependencies of capitalists. Roman soldiers who converted to the Way no doubt stuck hard at the injunction to love their enemies.

And we, what do we find difficult? Paul’s common sense about husbands and wives.

Headship Absorbed

When people are in theological straits, they resort to the safety of arguing that Jesus or Paul did not mean what the plain sense of the text suggests. Thus, some absorb the husband’s headship into the humility, rather as a paramecium is absorbed into an amoeba; so I have seen servile Christian men tout their obedience to this verse because in “sacrifice,” in Christlike sacrifice, they allow their wives to do whatever their wives please.

I have also seen the sense so transmuted that headship is reduced to a cipher, since all the really important Christian work is in service. It is as if Paul had said that the husband was to be the figurehead of the wife. Such exegetes had better watch lest Christ become but the figurehead of their churches.

I think, rather, that cutting stone out of a mountain sheds better light on Paul’s words: A stick of dynamite is worth a sheaf of exegetes. Properly understood, there must be something dangerous and alive about the headship of the husband. After all, headship was not safe for Christ, nor for his people—that is to say, it was not comfortable, was not, is not, nor ever shall be what the members of his body, the Church, would choose for themselves. To be a man as Christ was is to embrace the danger, not in bravado but in deep humility.

For God has created us men to be the ones who do not give birth, and who therefore are, as a brute biological fact, dispensable. Therein lies our glory and the claim we justly make upon our wives. A man is indispensable, so to speak, only insofar as he assumes the danger of leading in faith and love. Such a man knows that the breath in his lungs is of no consequence. Lower the rope, he calls to his comrades at the top of the cliff.

Women, as a brute biological fact, are indispensable. They bear children, wherein their glory lies and also, if we may trust Paul’s mysterious words, their salvation. In humility the woman is called to acknowledge that indispensability and to bind herself to it, in physical or spiritual motherhood. In humility the man is called to recognize that he matters as a man only if he knows that he does not matter at all, and to allow himself to be severed, if need be, from those he loves most.

True Soldiers

The humility of risk is perfected in Christ and is, even when marred or hidden by the swagger, essential to natural manhood. The men of all really thriving cultures know that their lives, if truly lived, are not their own. The samurai was taught to relish each day as one won from death, an unexpected boon: For the moment he swears allegiance to his lord, he must consider his life as already forfeit. Thus, he can lay that life down at a nod, whenever the sacrifice should be required.

Men who went down to the sea in ships, Viking marauders or Nantucket whalers, knew well they might never return, yet they did go; and the man on the mizzen in the midst of a storm knew that his life literally hung by a thread, and that many of his fellows in just his situation never saw land again, but without him and his obedience there could be no voyage beyond the calm of a bay. The crewmen on the Titanic held it as their duty, once the iceberg’s devastation had been reckoned, to assume that their lives were lost. Only so could they tax their muscles and their broken hearts to the last stretched fiber, to save as many other souls as they could, particularly women and children.

The lad who carried the flag in the old fields of war was unarmed and most conspicuous, but most necessary for the rallying and ordering of his comrades. He was indispensable in his choosing the honor of being the single man least likely to survive the battle. The man first up the ladder to scale the walls of a besieged city would likely also be the first man dead beneath; but if he does not go, no one goes.

The Spartans at Thermopylae knew they could not hold that pass forever against a Persian army many times their strength, but they held long enough for the Athenians to prepare for the onslaught. And you hold a pass by understanding that your life is not your life. You block the opening. The foe must break through over your dead body.

A man need not bear a saber to be a true soldier. When Louis Pasteur was searching for cures for infectious diseases, he had not our same luxury of safety. He was a devout Catholic who attracted to himself young men of high ideals and similar devotion. Those men knew that to be Pasteur’s assistant meant constant exposure to, and experimentation with, disease. Theirs was less a profession than a creed. They went forth in the wake of a plague in Egypt, to seek knowledge and cure the sick.

One gentle young man, like the holy Damien of Molokai, contracted the disease himself, and laid his body down in that alien land. The men embraced the risk. They were dispensable; the cause was not.

Strange Humility

This strange humility of the dispensable man may look like glory, in part because it really is glorious and is justly rewarded with glory.

When the Etruscan king Porsena had entrenched his soldiers around an uppity village called Rome, a youth named Mucius sneaked out of the city and found his way into the enemy camp unnoticed. There he saw an important-looking personage surrounded by officers and giving orders. Drawing his dagger, Mucius rushed the man and buried it in his stomach. But he was mistaken. It was Porsena’s secretary he had slain. The soldiers seized him and dragged him before the king, who sentenced him to be burnt to death.

“I came to kill you, and failed,” said the boy to Porsena. “You may execute me for that. I will not weep at the honor of laying down my life for my city. Do not rejoice,” he continued, thrusting his hand into the flames nearby, “but see the determination of a Roman. For after me will come another, and another, and another.” The hand burned, but -Mucius did not flinch. So stunned was Porsena by the lad’s virtue—a manly nobility, his having made himself wholly dispensable for his people—that he ordered the soldiers to set him free.

As for Mucius, his hand was useless from then on, so the good men of Rome tagged him with an affectionately insulting and reverent nickname: Scaevola, “Lefty.” Mucius bore it proudly as a new surname, and so it remained, commanding respect for centuries to come.

And the humility of the dispensable man may look like folly—like boyish high spirits, as a saner age than ours might say, or like immature and irresponsible risk-taking, as our schoolmarmish age does say. But my heart is with the boys and not the schoolmarm.

Gideon’s Men

As thick as grasshoppers were the Midianites when they beset the people of Israel, burning their crops and driving them into the clefts of the mountains to hide. But the Lord chose a youth, Gideon, to drive them out. Gideon seems not to have been, at first, a particularly devout -follower of the Lord. He was a young man of his day, one who combined a canny caution with utter temerity. He puts God Almighty to the test, requiring of the Creator of the universe empirical evidence by way of signs, and even making double sure by asking God to switch those signs around.

Yet once the signs are given, we hear no more about Gideon’s caution. For this is the same Gideon who would be arrested for vandalism, having gone out with ten of his servants in the dead of night to pull down the altar of Baal. That feat earned him a nickname, too. When the Midianites came to his father Joash to accuse the boy, Joash cunningly said that they themselves were blaspheming against Baal, tartly observing that if Baal were really a god, then Baal could come down and plead Baal’s own case. So Gideon became known, with the relish of derision, as Jerubbaal, or “Let Baal come down!”

Now how do you choose an army to defeat a people as swarming as the Midianites? Simple. You recruit as few men as possible, and you employ no known tactics of war. Trusting in the Lord is never “safe.” So the Lord himself thins out Gideon’s army by removing from it all those who think to save their skins. That cuts it by more than two-thirds, leaving Gideon with ten thousand men.

Still too many for the Lord, who wishes to show Israel that the battle is his, not man’s. So he devises a strange and amiable way to cut the army to the bone. “Bring them down unto the water,” he says. “Everyone that lappeth of the water with his tongue, as a dog lappeth, him shalt thou set by himself; likewise everyone that boweth down upon his knees to drink.” Those who lap like dogs are taken; everybody else is sent home. Gideon now has three hundred men.

What are we to make of this? A convenient but otherwise meaningless device? Not so. Note the care with which the many minister to themselves, and note the doglike eagerness of the few. The true men, they who surely thought their lives would soon be dust, are most like happy children, boyishly ready to fight, never mind the delicacies. And when, that night, they sweep upon the Midianite camp, each bearing a pitcher to smash and a trumpet to blow and a sword for the enemies pitched into confusion, they rally by crying, “The sword of the Lord, and of Gideon!”

Not their own names do they cry, but the names of their generals. They are the dispensable three hundred, the remnant, the stump of an army; they are the naked boy against an armored giant, a half-mad prophet against the cosmopolitan Jezebel, an old stutterer against the emperor and god of Egypt, a babe in swaddling clothes against all the powers of darkness.

A Man’s Answer

So the boy has his friends lower him down on a rope, and he paints United We Stand on the wall of a quarry where it is illegal for him to be. Why? What can come of it? He can be caught and arrested, earning a hefty fine for his parents. He can—it does happen—fall, perhaps die. Not one terrorist will set aside his enmity because of it. No hill will be taken, no city freed, no countryman brought home alive. Yet he does it.

Set aside all questions about the justice of the war. You cannot be a man, you cannot know about manhood, if you can find no answer to that question. You do it because it ought to be done. You do it because you sense that, in the present circumstances, you are not important. Indeed, you are dispensable. The country is important. You do it (and you are probably proud of it, and cannot resist showing it to some pretty young lady) because you acknowledge order and hierarchy: something greater than yourself, to which you pay honor. You kneel, and you hold your head high.

I need hardly say that if American boys are taught such lessons today, it is by accident. A good coach or a policeman can teach them; but in general, boys are taught two incompatible falsehoods. First, they and everyone else are taught the narcissistic notion that the individual and those skittish electrochemical blinks which he is pleased to call his “opinions” are all-important, and that he ought to fight any attempt to enlist his obedience or to stir his homage towards the truly excellent.

Second, he is taught that somehow his own longings and his masculine desire to impose structure and order—hierarchical order—upon chaos are inferior to the all-embracing tolerance of his sisters. To obey is to grovel, unless it is a man obeying a woman. The boy is taught not that he is dispensable. All brave and true men have agreed to become dispensable. He is taught that he is unnecessary, and that is quite a different thing.

It is as if a helmeted and holstered policewoman were to ticket my quarry painter, smiling benignly to herself and shaking her head at his immaturity, agreeing to impose the indignity of a light reprimand and a course on safety.

Or it is as if Mary, plena superba after the descent of the Spirit at Pentecost, were to assume headship of the Church, preaching the ever-safe doctrines of man’s -inherent goodness and the equality of all religions, advising her social workers to go forth unto the ends of the earth, even unto Bangor, and be baptized by whatever name should be popular there on that day; rendering unnecessary her own Son, the indispensable Savior himself, whose life was to be dispensed for his enemies.

We do not need a savior, do not need the Man, and can smile at his fevered idealism, his submission to, of all things, a Father in heaven. We grieve about the Cross, but think that if Jesus had only learned of his own true importance, he never would have tossed his life away. It is as if a Parks Commission were to whitewash the graffiti of the Gospels.

Forgetting Men

Or, more outlandish still, it is as if men themselves were to forget their manhood and were to coddle their flesh, prinking it and bedaubing it and festooning it with trinkets, while cheering their daughters on in the games of war and sending them off with tears to the real thing; as if these same half-men should consign their boys to be raised by women, for women, and as women, depriving them of healthy and culturally dynamic ways to satisfy their longing for danger, their need to be needed, their chance to stand tall in obedience to duty.

It is as if they were to snatch the very Cross from the shoulders of those young men still inclined to take it up. It is as if the hard edges of this wondrous and dangerous world, hard as slate, real as the Welshmen who jammed their pickaxes into it and sawed it and hauled it away, were to be softened and rounded and padded.

United We Stand? A few of us anyway, my brave fellow. May the Lord soon reduce us to three hundred.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on fatherhood from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor