Feature

The Creed We Need

On the Picture of God We Draw with Words

by David Mills

God is “agapic love,” the preacher said, and paused. “God”—I knew what was coming, the man being mired in the sixties—“is a verb.” He assured the congregation that as long as they were “doing agapic love,” that—left undefined—was all they needed to do. I could hear around me the sighs of people who have heard something they wanted to hear.

“God is a verb” is about as much doctrinal complexity as many American Christians seem to want, vague and useless as it is. They do not want anything too precise and specific, for that means exclusive, intellectual, and binding, nor anything too old, for that means irrelevant.

Average Agnostics

The average American thinks that when lots of nice people follow different religions, no religion should claim to be true in such a way that the others must be false. Everyone is happier, and no one will start fighting, when religion is a matter of taste, enjoyed privately, like an ethnic food. No one minds if a Scotsman eats haggis, as long as he eats it behind closed doors, but no one would tolerate his attempt to make it the sole main course in the high-school cafeteria.

The non-religious will explain their dislike of doctrines by saying that we ought to live and let live, that people are different, that religion is a private matter, and the like. The religious will explain it in two ways. One type (the believer) will say that Christianity is a matter of the heart, or a personal relationship with Christ, or that he has no creed but the Bible. The other type (the skeptic or liberal) will say that all religions seek the divine power which lives “beyond the images that bind and blind us all,” as one modern heretic once put it, or that we are all climbing different slopes of the same mountain, or that we are all blind men trying to describe an elephant.

If he is consciously religious, this modern American also dislikes being bound to the kind of creeds and confessions most churches require (in theory) of their members. (In some churches these confessions have not been articulated, but they are understood and enforced nonetheless.) He wants his beliefs put broadly and vaguely, flexibly and changeably.

And he deeply dislikes the technical language of theology. He will tell you that phrases like “begotten not made” and “of one being” do not mean anything useful or (if he is more learned) that these words represent not the ancients’ idea of Christian truth but one party’s victory in an essentially political contest.

If he has read his postmodern writers, he may say that the doctrinal statements mark a community’s shared identity but do not establish a truth to which it is bound (the Fatherhood of God being our way of saying that the universe is personal), or that they help one group oppress another (men assert the Fatherhood of God to justify the power of men over women).

This kind of Christian rejects doctrinal rigor mainly in religion. He does not want his surgeon to be as vague about his heart as he expects his church to be about Christology, nor his mechanic to call the carburetor “that thing on top that sends the gas around” though he would be happy to hear his pastor call the Holy Spirit “a kind of power God sends us.”

He does not want his accountant to treat the technical language of tax law as irrelevant to real life, nor the architect who designed the building in which he works to declare the laws of physics merely a political victory of one party over the other in the early modern period. He does not want the umpire at home plate to insist that the strike zone is merely a matter of identity (baseball has to have a strike zone to be baseball), he wants him to see it as something already defined that binds the pitcher, the batter, and himself.

These are matters about which he will be dogmatic. Why does he think it more important to describe the heart than to describe the creator of the heart? Why does he think the details of the tax law more critical than the details of God’s law, and the moral law any less fixed than the strike zone? The answer, I think, is that he knows hearts and carburetors to be real but is not quite sure that the Father and the moral law are.

What Christians Do

I generalize here, but do not exaggerate. In contrast, the traditional or Mere Christian insists that we should have a settled doctrine of some complexity, and that indeed we already do. Our confessions differ greatly, but every Mere Christian accepts the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds as accurate statements of Christian truth, whatever authority his tradition gives them. Here I will talk about the Creed (meaning the two ancient creeds), because they summarize the doctrines shared by Mere Christians, but my arguments apply almost as much to the more elaborate confessions of our various traditions.

We hold to the Creed we have been given for several reasons. The first and main reason is that this is what Christians do. We, being individualists and rationalists, tend to forget this. We think we can accept only what we can accept, but nothing in Scripture nor in the early tradition suggests that we get to pick and choose. In for a penny, in for a pound, as St. Paul might have said.

Nor do you get to pick and choose anywhere else, if you are an honorable man. You do what your community does if you want to take your place in its life, whether or not you like everything it does, and whether or not you understand everything it does. The good man does not quibble about it, but sets himself to learn in obedience.

So when you have married into a family, you drag yourself to their family reunion and to the wedding of the nephew you’ve never liked. You dance with your new spouse’s grandmother even if she steps on your feet and smells bad, and you help paint her house even though it means spending the day listening to cousin Harold’s rap music played very loud. The more traditions your new family has, the more difficult fitting in will be—if your name is Percy Standish Oglethorpe IV, for example, and you marry into one of those Greek families you see in the movies—but you do it anyway. That is what it means to be married.

The Church is the greatest family you have entered, and you joined of your own free will. (Even if you grew up in it, you have chosen to stay.) You joined it because you knew you could trust it to get things right, not least the truth about the universe. As G. K. Chesterton said somewhere, you not only discovered that the Church had told the truth on this or that matter, but discovered the Church as a truth-telling thing.

Once you have chosen the faith, you cannot choose the parts you like and leave the rest. If you have joined a church, worship by her rites, read her Scriptures, pray her prayers, accept her pastoral authority, and receive her sacraments, it makes no sense whatsoever to reject the doctrines that explain and justify doing so. It would be like joining the Libertarian party, going to its meetings, funding its causes, doing its work, and voting for its candidates, while believing in the nationalization of major industries. That would be stupid. So is joining a church and holding some mutilated form of the creed.

The Liberating Creed

Believing the Christian Creed, firmly, truly, and without selection, is part of what Christians do. It is what you do when you join the Christian family. But obedience can only get you so far. It gives you a reason to do what your new family does, but at some point you should be able to explain why the family does what it does.

Just why do Christians insist on the Creed? Why do we put our beliefs in this ancient, complicated, difficult form? The simple answer is that we hold to the Creed because we have good news to proclaim and face a host of errors of which we need to be warned, and in both cases we must get the details exactly right. To put it another way: because we are human, and less than human.

We see this in the evolution of the Church’s two major creeds. The Apostles’ Creed (said only in the Western Churches) developed first, as the natural declaration of faith new Christians made at their baptism. It is primarily a joyful declaration of the truths to which they were giving their lives—and for which at any moment they might have to give their lives. It is like the American flag an immigrant waves as he says the oath of allegiance or the “I do” in which a man and woman proclaim their unbreakable commitment to each other.

The Nicene Creed (using wording derived from baptismal creeds) was written by a succession of Church Councils starting in the early fourth century to define the Faith ever more accurately because people were saying the wrong things about it. It was primarily a defense against error.

The first errors spoke inaccurately of Jesus, and of his relation to the Father. Most Christians knew that Jesus was fully God and yet fully man, but some effective writers in their own ranks said that Scripture taught that he was one or the other. They made good arguments for this, often intending to defend crucial Christian teachings, and could provide verses from the Scriptures supporting their claims.

The Church had to say something, because a Jesus who was less than man or less than God was not the Savior. A religion based upon a mistake in either direction (God but not man or man but not God) would not last, because its Jesus could never bridge the gap between sinful men and their Creator. The whole point of the thing was that the Jesus incarnate of the Virgin Mary was God of God.

Thus the Nicene Creed is longer and more technical than the Apostles’ Creed partly because it is like the law, which starts simply enough (“thou shalt not kill”) and gradually must become more complex and exact as first one problem presents itself (“thou shalt not kill, except in self-defense”) and then another (“thou shalt not kill, except in self-defense, and those thou shalt not kill include the unborn”). It grows more elaborate not because Christians like elaboration, but because people keep getting things wrong.

For example, some Christians read about Jesus’ baptism (Matt. 3:16–17) and decided that Jesus had been a man who was so good that God adopted him as his Son. That’s one way of looking at it, and as good as any, says the man who dislikes theological precision.

But the thoughtful Christian knows that the idea is quite wrong, and being quite wrong about Jesus, quite bad for us. The Adoptionist reading means that if we try very very hard to be good, we might get so good that God would adopt us too. This is, obviously, an idea that can destroy lives. Some will grow convinced of their great virtue, and presume upon God and man, while others will grow convinced of their wickedness, and despair.

To correct this mistake, the Church needed something more than the “Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord” of the Apostles’ Creed, which did not exclude the idea that Jesus had only become God’s Son during his life. An Adoptionist would say that with pleasure, treating the “only” as meaning “the only one at the time” or “the first.” That is one reason we have the “eternally begotten of the Father, begotten, not made” of the Nicene Creed.

Good News First

Notice that the Creed as proclamation developed before the Creed as defense against heresy. The witness given in the Creed is first joyful because it is Good News. It is only secondarily defensive, and then only because in a fallen world a witness to the Good News must be protected from being twisted into Bad News.

The Creed expresses the Good News in three ways. We have creeds because God made us to make them, because we want to know all about those we love, and because we have a history we rejoice to tell and retell.

We have creeds, first, because we were created to make them. God made us rational creatures. We like to put our facts and ideas in order. We like to find what relation they have to each other, to discover hidden agreements, resolve apparent contradictions, test them against challenges, apply them to new ideas, draw out new implications. As G. K. Chesterton wrote, “Man can be defined as an animal that makes dogmas.”

To the making of dogmas, however, someone always objects that “you can’t put God in a box” or another of a dozen or two similar lines that sound more profound than they are. The problem with these claims that try to claim humility for the skeptical rejection of the ancient Creeds is that Christianity declares that God has for us men and our salvation put himself in a box, in the body of Jesus and (in a slightly different sense) in the words of Scripture.

In making the Creed, the early Church was only declaring in a short form what God has revealed to us. It does not tell us everything we must know, but what God has decided we needed to know about himself. The Creed does not bind and blind us, because our Lord has bound himself to give us our sight.

It is easy to think that you are being humble—bravely refusing to put God in a box—when you are really just ignoring what you have been told. The first question to ask is not what we think we can know, but what we do know.

The Christian does not begin with an idea of the ineffable, distant, utterly transcendent, wholly other Divine, before which we can only bow, or shrug, or ignore, since it does not have much to do with us, but with the belief that God so loved the world that he sent his only begotten Son, and that he had prepared the world for his Son through a people whose history, poetry, and theology we have, and that his Son gathered a set of companions who could speak for him and who would carry on his life through human history.

To the Christian, the skeptic proclaiming his humility before the mystery of the Divine looks rather like a man with a crushing headache standing outside the drugstore and telling passersby how great a mystery is the human body. It is a mystery, true, but on the other hand, just twenty feet away are medicines that would cure his headache.

Childish Skeptics

The English theologian Friedrich von Hügel once told his niece, in advice included in Letters to a Niece, to “shrink away from the childish attitude” of those who said that it does not matter what we say about God, because we can’t really know anything definite about him. He noted that we can never completely know or adequately define a daisy or a pet dog or a friend, but even so, we can still know them well. It very much matters what we think of them, because some ideas are “ever so much more penetrating, ever so much more true” than others.

Think of anyone you know well, one of your children having trouble in school, say. It is true that however much you love him and however closely you have observed him as he grew, he is still in many ways a mystery. You do not know why he does everything he does, why he feels the way he feels. You see him through a glass darkly, and a parent will know how painful that can be.

Yet you do know him well, better than his teachers or his doctors, even his brothers and sisters. You know, or can guess, why he does some things he does, why he feels the way he feels. Your insight is ever so much more penetrating, ever so much more true than others’, and therefore you will know what he needs more surely than others, even those who may know more about child development or early adolescent psychology than you.

What the Church has said in the Creed is partial and incomplete, but it is true and sufficient for our needs. It is a box that holds what God has given us to hold in this way. We see through a glass darkly, as St. Paul said, a verse the childish skeptics sometimes invoke to defend almost complete agnosticism, but we do see, as Paul obviously knew.

We can read the big words on the billboards across the street even through a filthy scratched window, even if we cannot read the bumper stickers on the cars parked at the curb. And the billboards say things like “For God so loved the world . . .” and “begotten, not made.”

So the Creed proclaims the Good News, as expressed by people to whom God has given the gift of putting their knowledge in order. When the believer says the Creed, he is only saying, in greater depth, the words of John 3:16.

Memory & Celebration

So we hold the Creed because God created us to put our knowledge into words. We hold it for two other reasons: because we love to remember the things we love and because we have a history we love to celebrate and share.

The second reason we have and hold the Creed is that it helps us remember and celebrate the God we love. We are curious creatures who must know all about those we love, and festive creatures who must talk about them all the time. To put it another way, the Christian holds to the Creed because the Creed is simply a handy and authoritative summary of the Church’s story, of his family’s story.

For this reason, the Christian story is a story in which the details matter. A man who thinks his blue-eyed wife has brown eyes does not really love her, and his heresy about the color of her eyes shows it. A man who thinks that Jesus was “made, not begotten” does not know him very well and, not knowing him, cannot really love him.

A man and woman who meet in the hall may talk about the weather and baseball or complain about the people at work or trade the names of their favorite Chinese restaurants. A man and woman falling in love talk about their second-grade teacher and the tricks their dog could do and their favorite books and their pet peeves. They love to hear stories that would bore them senseless were they told about anyone else, because these stories teach them something new about their beloved.

So with our love for God. We want to know all about him, what he has done, what he has said, what he is like, what he thinks of us and why he has done what he has for us. As with any human friend, to know him personally we need to know the central facts about him.

We need the Creed to be sure we know all we want to know, because, in part, many of the most important facts are not obvious. The Adoptionists were not obviously wrong, in the way a flat-earther is obviously wrong. They accounted for the data. They just accounted for it in a way that removed its power to save.

Appearances can deceive even the best-intentioned. And most of us are not always well-intentioned, and tempted to tame Jesus by removing him from the Godhead. Jesus the great prophet telling us about narrow ways and strait gates does not threaten us nearly as much as Jesus the Son of God telling us about narrow ways and strait gates.

As I say, the details matter. Those who only know the mild-mannered reporter Clark Kent do not really know Clark Kent. Those who only know the man Jesus do not know Jesus the Son of the Father. They may know him in the way they know the clerk at the post office or the waitress at the coffee shop, but they do not know him the way his close friends know him.

If they think that Jesus was only an inspired prophet, now dead, and do not know that he was “of one being with the Father,” they do not know the Son who will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead, including them. (This could prove to be a problem.)

Dying for Dogma

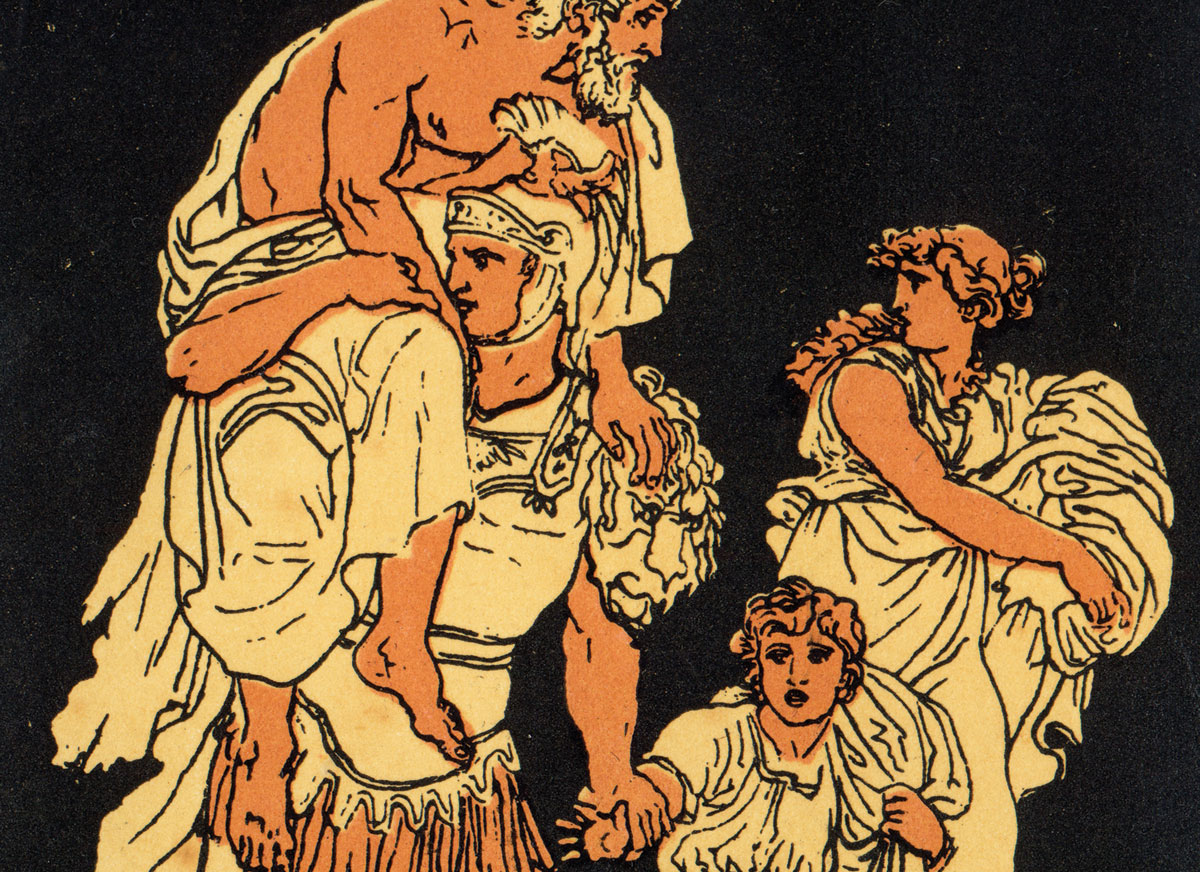

To put it another way, the Creed is like the picture of a loved one you keep on your desk or the picture of LeBron James the teenaged boy puts on his wall. It is the verbal equivalent of the icon or crucifix you hang above your desk.

This explains why so many Christians hold the Creed with such conviction, and why they will suffer and die for what seems to the unbeliever and the skeptical Christian a mere set of words. As John Henry Newman wrote: “Many a man will live and die upon a dogma: no man will be a martyr for a conclusion.” The Creed is not a conclusion, or not only that, but a dogma, a statement of the way we think the world is. And a dogma means a picture of the Man who died for me.

Men and women died in the Roman arenas because they would not deny that Jesus was the Father’s only Son, but as far as I know, no one has ever given his life, or even risked losing tenure, for the existential Christ of the demythologizers, or the itinerant Palestinian preacher of the skeptical New Testament scholars, or the religious philosopher’s Ground of Being or Ultimate Concern. They are conclusions, and at the point of death even the most egotistical suddenly admits that he might be wrong.

People will sacrifice themselves for a reality: for their children, their home, their country, or their God. Christians will die rather than deny the Creed, because to deny it is to deny the God they love. It is not a set of propositions so much as a verbal picture, and therefore treated with the reverence with which we treat the pictures of those we love.

A History to Share

We have and hold the Creed for a third reason: because we have a history we love to celebrate and share. We take pride in the history and heritage of our community. We revel in the story of our tribe, our gang, our family—in our case, in telling “the old, old story of Jesus and his love,” as the classic hymn puts it.

The same is true of families. A member of the family enjoys telling and hearing its legends and stories over and over. If you marry into a family, you know you have truly become part of it when you can take a turn telling a family story at a family gathering and find yourself sharing them with outsiders.

And when you know perfectly the stories’ right form. Families tell their stories in long-established forms in which even the smallest details and the wording itself are settled. People will howl when the storyteller leaves out a detail or gets something out of order. The details matter, because they tell the family who they are.

It matters that it was uncle Alfred and not uncle Henry who set the tablecloth alight, and that it was aunt Mabel and not aunt Edith who shocked her parents by marrying a Presbyterian, that it was shy grandfather Andrew who fought in north Africa and blustering grandfather William who became an accountant. Each detail fixes a little more firmly the family’s understanding of itself—that in this family, looking at the two grandfathers, those who do not seek attention will do the bravest things.

The Church is a family, and the Creed gives the essential facts of our family history, arranged accurately and reliably and given us by the family’s patriarchs. It tells the children of God who their Father is and what he has done. It tells the story believers repeat to each other, celebrate together, and share with strangers.

The Creed is the family story in summary form, and you must accept it to be part of the family. If you want to be a Christian you must make it your own story. You assume that the story is rightly told. You assume that someone understands the parts of the story you do not—that “begotten, not made” business, for example—and that you will find out what they mean some day. Until you do, you tell it anyway.

Necessary Creed

And so we come back to ask why we bind ourselves to a Creed written so long ago and in such peculiar words. It is not, in our culture, a normal thing to do, binding oneself to a theoretical statement of some antiquity requiring some specialist knowledge to understand. Most of those who say the Creed in church on Sundays never otherwise read anything written so long ago nor think about such theoretical matters.

We bind ourselves to the Creed of the Fathers because this is what Christians do, and in entering the life of the Church, as understood by Mere Christians, we trust that she knows what she is doing. We trust, for many reasons and with reasonable assurance, that a formula is needed and that this is the right formula.

Beyond that, we have and hold the Creed because God made us to make it, because it tells us what we want to know about the God we love, and because we have a history to celebrate and share. To have and hold the Creed is a natural and (I think) necessary response to the Good News of the gospel.

Thus we dissent from the dogmatic indifference of our age—an indifference to truth that calls itself tolerance, forgetting that tolerance itself requires a dogma of the human person as a creature to be tolerated even when he is wrong—and insist on a Creed written so long ago and in such peculiar words, because it is true. We cannot live and let live by letting go our doctrines, or treat the ancient heresies (always newly packaged) as alternative expressions of a deeper belief every Christian shares, or worship a God we share with Hindus and Buddhists, because God has revealed himself.

That revelation has been distilled into the Creed, which tells us the truth about the Father and his Son and their Holy Spirit. The only choice we have is whether to accept or reject him, and whether or not to stand with the Church of the ages and turn to the Cross and say “I believe in God the Father. . . .”

This will be for some believers, more modern than they realize, a way of taking up the Cross. It will be for them a challenge much like that Jesus gave to the rich young ruler: to sell their intellectual pride and follow him, in the verbal form some of his earliest followers gave us, trusting that with him and them, they will find greater wealth than that they have just given up. They may have to stand uncomfortably for a while, mumbling words that seem to them pointless, until God rewards their trust and they see what they are saying, and then they may drop to their knees in thanksgiving.

Parts of this essay appeared many years ago in The Evangelical Catholic and Mission & Ministry.

|

|

David Mills has been editor of Touchstone and executive editor of First Things.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on ecumenism from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor