View

A Mighty Child

Anthony Esolen on an Apostle’s Encounter with the Son’s Children

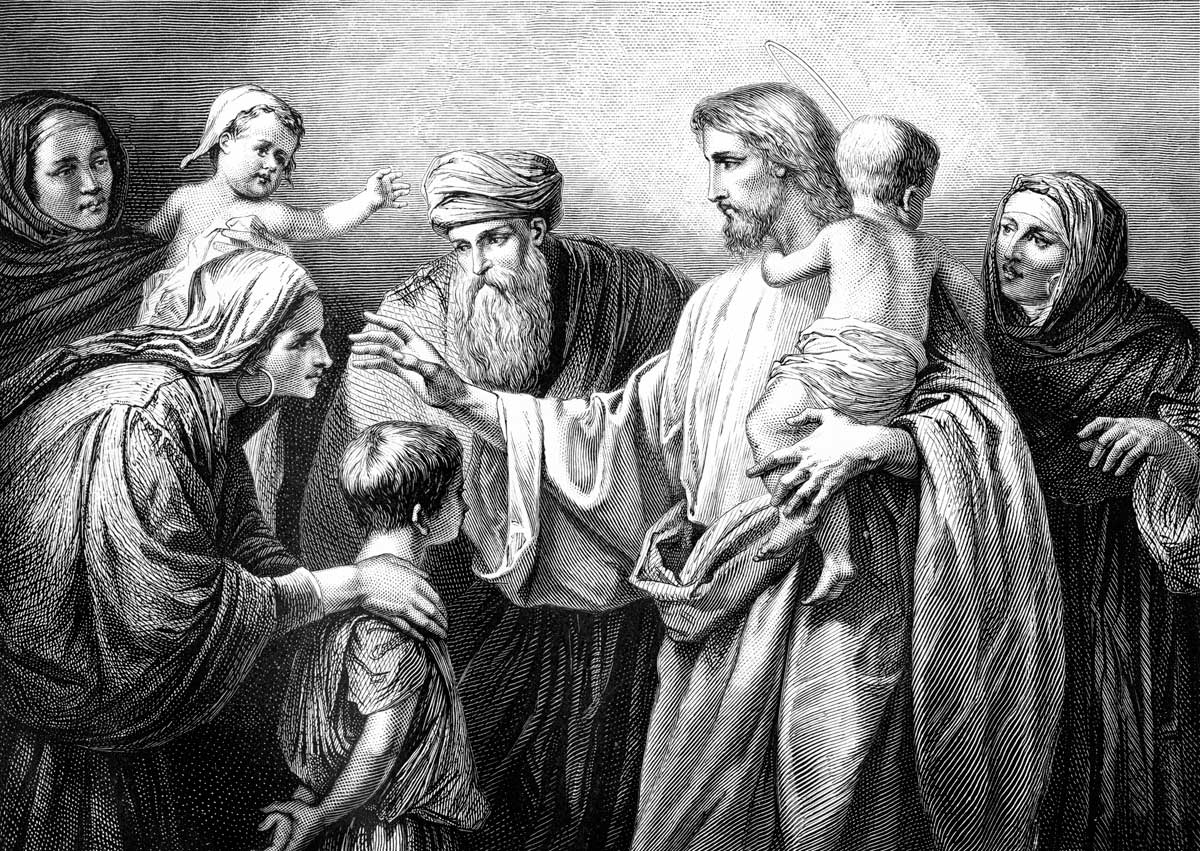

Always the same annoyances when the Teacher entered a village. If he was followed by a crowd—from the beggars who hardly understood what was going on even when they were sober, to the elders with sharp eyes, from louts eager for a show, to women ready to weep and faint—you could be sure of a couple of things. Little would get done. A scuffle would break out. The innkeepers would run up the reckoning. And mothers with their children would appear.

What strange sympathy makes every mother think her child beautiful? No sooner would the Teacher be seated, looking wan from the journey on foot and the bad meals, and not a bed to rest his head upon, when toddling up to him would come the children. Some bear the scuffs and scabs of falls. The girls twirl their hair round their fingers. One has a runny nose.

Several are toddlers with nothing on but a smock, and sometimes not even that, padding about in the dust and the puddles, bottoms messy and stale. Almost all are missing teeth, and in awkward combinations. Their eyes are big and peer out of their round faces. They are drawn to the Teacher, though they have never heard him say a word, nor would they understand it if they did.

Inevitably they begin to press upon him, dirty-lipped and hungry, looking to him for who knows what. Then one day we friends of his, always on the watch for his comfort, now rising in our own esteem to the high station of managers, organizers, officials, cried out, “Clear away, there! Let the Teacher have some room! Madam, don’t you see that the Teacher is weary? Let’s have a little order here!”

At which he heaved a sigh and said to us, “Suffer the little children to come unto me.” Rumpling the hair of one of the runny-nosed, he added, “Let them come, for the kingdom of heaven is peopled with citizens like these.” And he looked us in the eye. “As for you, unless you become like a little child, you shall not enter the kingdom of heaven.”

An Old Young Man

I thought he was just using a figure of speech. That was the way out—or in. You can drive a camel through a figure of speech. So I never gave his saying a lot of thought.

Who did, back then? We thought we were sharp observers, after all, grown men, and to be reckoned with. We had the angle on the chief priests, which of them were on the lookout for a Teacher like ours, and who in the Sanhedrin could be won over with the right word. We knew the right time to sit tight and the right time to move.

Great things were coming, we thought, but whenever we talked about the politics, which was often enough, the Teacher would walk off by himself or fall asleep. He was always going to Galilee when he should go to Jerusalem, or going to Jerusalem when he should go to Galilee. We scolded him about it, but he never listened.

We were important men with important things to do, older and wiser than our years. Sometimes we quarreled over who would be the councilors to sit at his left and his right, but we were all assured of becoming judges at least. As for becoming a little child, who could understand it? I would be like a child, let’s say, in my reacquired innocence, or in my obedience to the Teacher, or in some other way that you could age into, with dignity. That’s what I would do, and I was sure it would be good enough for him.

I was young then, you may say. That’s kind of you, but you’re wrong. Had I been young, I might have understood him. But I was old, very old. My name was Adam, every man’s name. My eyes weren’t creased, and this flesh on my arm didn’t sag, and my knees didn’t creak when I stood up.

But I had long since hardened into sin. I was ancient of heart. A fisherman’s ways are crude enough to begin with, and on land I was rougher than on the water. You can guess the trade: some brackish girl skulking around the moorings, ready to barter sin for a part of the haul. I knew the way of it, my eyes were quick. What was all that strength of limb and smoothness of cheek but a wrapping for an old, hard, dying heart? I wanted my way, the way to which I had grown accustomed.

Had I the power, I should have commanded every least flower of the field and bird of the air to be my servant, for my use. I should have aged and turned to stone everything I touched. For what did I do, even in those nights when the wine went round, what did I do but with my own hands hammer at the chisel, carefully, steadily, in dreary and lonely habit, spending all my life to carve my own tomb? That’s the way of all flesh. Listen to the clinking of the chisels.

But the One who raised Lazarus from his tomb raised me from mine. Do you think he has granted me many years to grow old? Nothing of the kind. He has granted me many years to grow young.

Childish Shadows

Please don’t mistake me. You’ll say, “I understand you. When a mother and a father have a child, the baby makes them young again. They lisp to him, they play again the games they had long given up, remember the rhymes they had long forgotten. You have yourself allowed our little children to come unto you, following the Teacher’s instruction, and they have renewed your youth.”

Well, they do help me remember the games, and the song of my mother. But we are dealing in shadows here, just as the Temple of Solomon was only a shadow of the body of our most blessed Lord. These childish things are good, yet good only in a shadowy way.

I believe I never had been the child the Teacher wanted me to be; and when those children came to him, dirty and bedraggled and impudent and shy, even they had already tasted sin. He wanted me not to become one of them again, but to become like them, and in a way not fully made real in themselves. He wanted me to be not young again, but young in truth for the first time. I might even say, to be young in glory.

Perhaps you are surprised to hear me talk of glory and not humility. But never take the children lightly. When they first come to us, in all their helplessness they look at us with eyes that seem to have come from another world, as indeed they have. We think we bring them into our world, and in fact, little by little, we do; we teach them to walk and talk, to eat at table, to read, to do right and avoid wrong, and, following in our own path, to do wrong and avoid right.

But I think they come not so much to be a part of our world, as to give us another chance to return to theirs. They are a perilous gift.

How can I explain it? Children come from God who made them, not from a “world,” yet they seem to break into this world so that we can break out of it. Does not the child destroy? Is he not a man of war? Think not only of the sleepless nights, the piecing out of the food, the undone work; think of those illusions, the dreams of the future, the projection of mother and father into posterity. Mother and father have their purposes, but the child has his, and comes to tear the illusion in two from top to bottom.

Good Dangers

It is true that the Lord sometimes allows the child’s sins to do the destroying, as Absalom broke the heart of David. Yet Scripture shows us how much more dangerous is goodness than sin. See how the virtuous Joseph slew the pride of his brothers and placed under his stewardship the most powerful nation on the earth. See how the young Samuel lived as a reproach to his master Eli, who had welcomed him into his house and taught him the worship of the Lord, and who was struck dead when he heard the news of the fall of his own wicked sons. At the least, with the birth of every child, the mother’s body is broken, and the father says, “He must increase, and I must decrease.”

Then if it is a child’s littleness you recommend, I agree, but look at the little children with the runny noses, the snaggled hair, the uneasy smell. Yet even such as these came up to him. Did they come humbly? Is it in humility that I am to be like a child? If they were humble, they were certainly impetuous enough about it, and I had all I could do to pull that humility away! They were humble—and brazen.

They all but strode up to him and said, “I want to be with you!” They didn’t pause to note their greatness, or their littleness. They didn’t say, “This is what I have,” or “This is what I lack.” They didn’t say, “Here is what I can do for you,” or “Without you I can do nothing.” Does a toddler understand himself as himself? Does he know he is naked? Even if he knows he is naked, tainted by sin though he may be, he runs up to the Teacher anyway and says, “I want to be with you!”

All was a gift for them then, as all is a gift for me now. When I was what the world calls young, I had my purposes, until he burst upon me in the flesh, preaching a bodily resurrection, a bodily food, and tearing my purposes in two. So did the Holy Spirit burst into the life of Mary. So too she tells us he came upon Herod, the child-murderer. Herod had his purposes, and all those who maintain their purposes, who hold the chisel steady, come Who may, end by murdering the child.

Mighty Child

We know who this child is who ruined my life, to make me his child: “For unto us a child is born, unto us a son is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder: and his name shall be called Wonderful, Counsellor, The mighty God, The everlasting Father, The Prince of Peace.”

Rome, they say, is growing old in childlessness. The cry of children is seldom heard, snuffed out to ward against poverty, or to cloak vice. The city has its purposes, walled up in marble, one vast memorial to itself, a barricade against the grace of God. The child comes to kick it down. Their own fables tell of a god who strangled the snake in his crib. They speak truer than they understand. When it comes to the ancient city, not a scorched stone will be left upon another.

But if before his return, this city should seize upon me and deliver my body to be burnt, I know, not by my own power but by the power of God who made me new, that I will run to him—as a child will run to his brother at the stake. I want to be with him—this is all I know. Friends, if you see my hand tremble as they lead me away, it will not be my age! Even now I hear him saying, “Suffer my little child to come unto me.”

To be with him is to be like him. Here on earth he was once a child, then a man, a man who would have grown old. Is it so in heaven? There, is his childhood past? My mind cannot soar so high. But I do know that Christ is the image of the everlasting Father, of him for whom a thousand years is as a twinkling of an eye, and a twinkling of an eye as a thousand years.

He has said that he and the Father are One. We call the Father the Ancient of Days, and justly so; but if so, then he is the first, and earlier than our imagination can fathom. He is even the child whom Simeon lived so long to see, and the old man’s heart leapt to behold him. He plays upon the waters. He renews our youth, because he himself is young: in the beginning, now, and evermore.

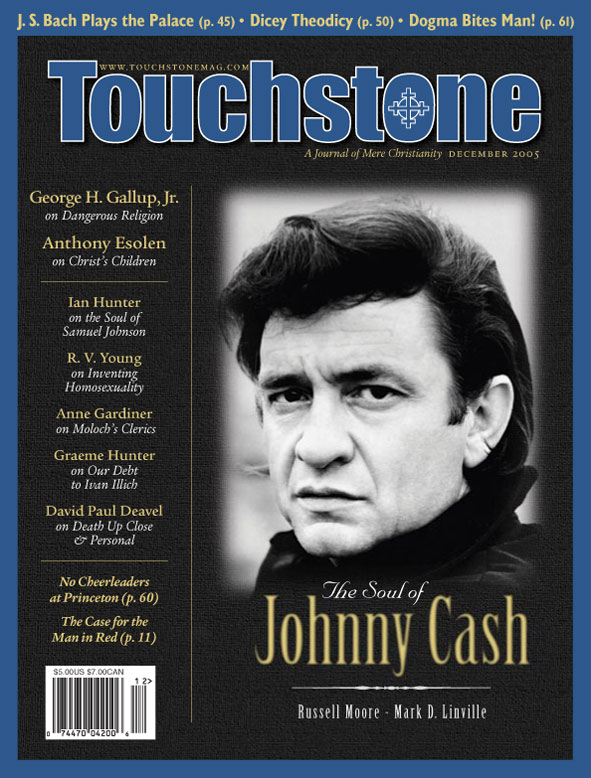

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor