Feature

Seeing Thro’ the Eye

The Prophetic Legacy of Malcolm Muggeridge

by Ian Hunter

No lines were more often quoted by Malcolm Muggeridge than this stanza from William Blake’s Songs of Innocence: “This life’s dim windows of the soul / Distort the Heavens from Pole to Pole / And lead you to believe a lie / When you see with, not thro’ the eye.” Seeing thro’ the eye was a particular gift of his, combined, fortunately, with compelling readability and a willingness to opine on almost any issue at almost any time.

Muggeridge spoke prophetically about many important events of the twentieth century. Prophecy is not so much a matter of predicting the future—though Muggeridge predicted some events with uncanny prescience—as seeing clearly truths others do not or refuse to see. If he was sometimes mocked and seldom heeded—well, that is the fate of prophets, as Jeremiah found out when he got himself chucked down a well. Prophets unsettle our preconceptions and disturb our complacency.

My purpose here is to call attention to what, in baseball parlance, might be called Muggeridge’s “box score,” in the no doubt vain hope that a man so often proved right might be accorded greater attention. I should make clear that Muggeridge himself did not claim to be a prophet. When others applied that label to him, he demurred: “I am no prophet, no, nor prophet’s son,” he said, adapting Amos. “I was a journalist and the Lord took me as I sat at my typewriter.” Yet even as a journalist, he saw through the eye what so many others, of greater fame and status, could not see because they saw only with the eye.

Gandhi’s Writer

In 1925, at the tender age of 22, Muggeridge took his first job, teaching English literature at Union Christian College in Alwaye, southern India. When he was not mocking the college faculty (“Mr. Dryasdust, B.A., B.L., author of notes on this, and notes on that and notes on every possible thing except on life. . . .”) or the students (“The Indian undergraduate is a strange being. He imagines that to be impressive, he must be pompous.”), he was stirring up nationalist sentiment against the colonial administration of the British Raj.

This was particularly evident after Mahatma Gandhi, at that time relatively unknown, paid a visit to the college in March 1925. Muggeridge thereafter corresponded with Gandhi, who published his letters in his newspaper, Young India, thereby earning the distinction of being Muggeridge’s first publisher.

These letters pressed two themes: (a) the impossibility of changing society without first changing men’s hearts; and (b) the artificiality and fragility of a colonial set-up that appeared to most people impregnable. The latter was an early application of his conviction about the futility of trying to live by the will as opposed to the imagination; this theme he derived from his friend Hugh Kingsmill, and it was one to which he returned almost as often as he spoke of seeing through the eye.

To the discerning eye, both themes are evident in a passage, first published in the Calcutta Guardian in 1926, where Malcolm is describing a retarded boy who drove geese, a boy whom he regularly saw on his nightly walk along the Parur Road. It demonstrates how consistent Muggeridge’s writing “style” (a term he detested and never used) remained through his life:

He carries no stick to assist him in keeping order amongst them, but only a large leaf, which he waves slowly to and fro; and one might easily imagine that his speech was nothing but the noise of the wind through this, so like is it to the sound of a forest when, in the evening, a light wind blows. With this he keeps his charges as a compact, disciplined company, not stupidly military in their orderliness, yet not by any means a rabble; rather they remind one of a band of pilgrims, or of workers working voluntarily together. They seem to be not so much numbered and uniformed as to make a harmony of which he is the conductor: not so much to march in step as to dance with perfect understanding of each other’s movements.

One day he saw another boy driving the geese, “a bouncing, bumptious fellow, who carried a switch like a sergeant-major, and who shouted at the geese as sahibs shout when they want something.” Predictably, the geese ran around squawking, some getting lost and others run over. He will not draw a moral from the contrast (“a thankless task”), but writes instead that he envies the first boy.

I feel that he has found the secret of happiness in that he has done one useful thing which he can do superlatively well, and that he is content to go on doing from day to day until he dies. When his soul leaves the poor, puny body, with its gapingly vacant face, I believe it will be found to be a rare and beautiful soul, pleasing to its maker. Sometimes I wonder about him—whether he will marry; whether he prays or has any kind of religion; whether he ever wonders about the meaning of things. All this is doubtful; what is certain is that he can drive the geese efficiently; and to do that is quite as worthy of praise as to write a book or bleat a lecture or drone a sermon or do any of the things we wretched intelligentsia preen ourselves on.

A Daring Prophet

Muggeridge returned to England, where he wrote leaders (editorials) for the Manchester Guardian, the leading newspaper of progressive opinion of its day and the height of achievement for the young, idealistic socialist that he then was. After a teaching stint at the Egyptian University in Cairo, his first stage play, Three Flats, opened at the Prince of Wales theatre on February 15, 1931. Its frankness about sex offended some critics—and even some members of his own family—but the play’s theme, namely, the destructive effect of high-rise living on individuals and families, would later become fodder for urban planners and sociologists. Again, Muggeridge was ahead of his time.

In 1932, Malcolm and his new wife, Kitty, left for the Soviet Union, where Malcolm was to serve as a correspondent for the Guardian and the Christian Science Monitor. It is arguable that the next 15 months gave rise to Muggeridge’s most prophetic journalism. Early in 1933, he did a daring thing: He had his Russian interpreter buy him a railway ticket to Ukraine and the North Caucasus. What he saw on that extended rail trip he would not forget; years later, he wrote that it “remained in my mind as a nightmare memory.”

He saw the richest wheat lands of Europe turned into a wilderness. He saw famine “planned and deliberate; not due to any natural catastrophe like failure of rain or cyclone or flooding. An administrative famine brought about by the forced collectivization of agriculture . . . abandoned villages, the absence of livestock, neglected fields: everywhere, famished, frightened people.”

In a German settlement, a little oasis of prosperity in the collectivized wilderness, he saw peasants kneeling down in the snow, weeping, and asking the settlers for bread. In his diary he made this vow: “Whatever else I may do or think in the future, I must never pretend that I haven’t seen this. Ideas will come and go; but this is more than an idea. It is peasants kneeling down in the snow and asking for bread. Something that I have seen and understood.”

And he saw an embryonic outline of what we now know (thanks to the courageous witness of Alexander Solzhenitsyn) as the Gulag Archipelago. At a railway station one gray, early morning, he saw a line of kulaks, or supposedly rich peasants, “with their hands tied behind them being herded into cattle trucks at gunpoint . . . all so silent and mysterious and horrible in the half light, like some macabre ballet.”

In a series of articles for the Guardian, Muggeridge wrote of what he had seen. In February he described the famine as “a state of war, a military occupation.”

[T]he grain collection has been carried out with such thoroughness and brutality that the peasants are now quite without bread. Thousands of them have been exiled; in certain cases whole villages have been sent north for forced labour . . . The fields are neglected, and full of weeds; no cattle are to be seen anywhere, and few horses; only the military and the G.P.U. [the secret police] are well-fed, and the rest of the population obviously starving, obviously terrorized.

The next month he wrote a three-part series tracing how the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” had become the Dictatorship of Joseph Stalin and then how the Dictatorship of Stalin became the “Dictatorship of the General Idea.” He concluded: “If the General Idea is fulfilled it can only be by bringing into existence a slave state.”

Denunciation

Such reporting produced a chorus of denunciation. The policy of the British government, and the inclination of the chattering classes, was wholehearted support for what was then called “the Soviet experiment.” (The Guardian itself spiked some of his articles and rewrote others.) Muggeridge was denounced as a liar—even “an hysterical liar”—by such eminent personages as the Very Reverend Hewlett Johnson, dean of Canterbury, who had from his pulpit praised Stalin’s “steady purpose and kindly generosity,” and by Harold Laski, legal scholar and Labour party guru, who assured all who would listen that the Soviet economy was a model of efficiency and equality and that the show trials of the Old Bolsheviks were models of judicial fairness.

George Bernard Shaw, who had just returned from a visit to Russia, also contradicted Muggeridge’s accounts of famine by describing granaries full to overflowing, attended by apple-cheeked granary maids. Even Malcolm’s aunt by marriage, the Fabian Socialist star Beatrice Webb, joined the chorus, repudiating his assertion that forced labor existed in the Soviet Union; when pressed in private conversation, she did acknowledge, almost wistfully, Malcolm noted, that “in Russia, people do disappear.”

Muggeridge’s reporting was contradicted preeminently by Walter Duranty, Moscow correspondent for the New York Times, a man whom Muggeridge later called “the greatest liar I have ever met”—a reporter who nonetheless was awarded a Pulitzer prize for his reporting on the Soviet Union. If vindication was a long time coming, it came in 1990, when Susan Taylor, in her biography of Duranty, Stalin’s Apologist, wrote that but for Muggeridge’s “stubborn chronicle of the event, the effects of the crime upon those who suffered might well have remained as hidden from scrutiny as its perpetrators intended. Little thanks he has received for it over the years, although there is a growing number who realize what a singular act of honesty and courage his reportage constituted.” Alas, by the time Susan Taylor wrote that, Muggeridge was dead.

In 1933, the Guardian sacked him, and he went to Switzerland, where he poured out his anger in a polemical novel, Winter in Moscow, which, for the next four decades, circulated in samizdhat through the Russian literary underground. It was his Russian experience that first prompted a reevaluation of Christianity. As Muggeridge put it four decades later: “My disillusionment with the notion of a predestined progress towards a kingdom of heaven on earth led me inexorably back to the kingdom not of this world proclaimed in the Christian revelation.”

Writing in 1937, in the journal Time and Tide, Muggeridge made an astonishing prophecy: At a date when Alexander Solzhenitsyn was a teenager, and most other dissident Soviet writers had not yet been born, he wrote: “Perhaps a new literature will come to pass in Russia, as once it did in the darkest days of Tsarist repression. If so, it will be a literature of revolt and so anathema to the Soviet establishment. Perhaps it is being scribbled even now in concentration camps and other dark corners. . . . Not even Dialectical Materialism, not even that, can put out the light of genius.”

He made a similarly prophetic comment in 1978. I happened to be staying with him when a Roman conclave chose Karol Wojtyla to become pope. “It is the end of the Soviet Union,” he said to me. “They will not be able to withstand the moral authority of a pope from the eastern Communist bloc.” Another prophecy that he did not live to see fully vindicated.

The Thirties

For a brief period in 1933, Muggeridge worked on a study of labor cooperatives under the auspices of the League of Nations in Geneva. That he entertained few illusions about the efficacy of the League is evidenced by this concluding stanza of a poem he wrote:

The place was set, the nations met,

They were a League of Nations;

But a League that seems, except in dreams,

To be little but orations.

When, in due course, the defunct League was replaced by the United Nations, Muggeridge was similarly dismissive; he called its New York headquarters “that huge symmetrical glass tombstone, whose occupants specialize in throwing stones.”

Incidentally, it was when Muggeridge was at the League of Nations that he met (at the Café Bavaria, his favorite Geneva haunt) a free-lance journalist with the ineffable name of P. Beaumont-Wadsworth. Once, in the fading light of an autumn afternoon, this worthy delivered himself—casually, apropos of nothing in particular—of a line that Muggeridge afterwards insisted could serve as the twentieth century’s epitaph. P. Beaumont-Wadsworth looked up from his glass, and said: “You know, I sometimes wonder if I’m licking the right boots.”

In 1935, his Russian articles having rendered him unemployable in the British press, Muggeridge returned to India, this time as assistant editor on the Calcutta Statesman. He returned to England in the late thirties, where he collaborated with his friend Hugh Kingsmill on two volumes of newspaper parodies: Brave Old World (1936) and Next Year’s News (1937).

Both of these books fell victim to the satirist’s nemesis, namely, that world events were far more bizarre than anything he could invent. Just by being themselves, Muggeridge complained, public figures snatched the bread from the satirist’s mouth. In Next Year’s News Muggeridge and Kingsmill envisaged a non-aggression pact signed between Hitler and Stalin—three years before Stalin and von Ribbentrop met secretly in Moscow to conclude the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact.

Throughout the late 1930s Muggeridge wrote frequently of the inevitably of a world war. After Neville Chamberlain made two obsequious trips to meet Hitler in Germany, Muggeridge wrote that “England has surrendered to coercion . . . because of cowardice and unenlightened self-interest.” War, he declared, would come sooner rather than later, because of the policy of appeasement.

After Chamberlain’s third and final trip, at the moment when Chamberlain was waving about his piece of paper and being lauded for having secured “peace in our time,” Muggeridge responded with an open letter to the British Government. “No words exist to express my scorn,” he wrote, and then, typically, went on to find just the right words. “I ask myself whether if you had been asked to kneel down . . . and with your face in the dust sing the Horst Wessel song, you would have raised any objection? I do not think you would have . . . although, of course, you would have preferred someone to act as your proxy.”

The War Years

The Second World War was underway by the time Muggeridge put the finishing touches to his The Thirties, a social history of a decade that began, he wrote, in the hope of progress without tears and concluded in the reality of tears without progress. This book (published in the United States as The Sun Never Sets) was his most successful book to date. It would remain continuously in print for three decades; when it was reissued in 1967, reviewer Philip Toynbee called it “a strange visionary portrait . . . the deep, penetrating boom of a prophet in full flight.”

One particular sentence from The Thirties that lodged itself in my mind is this one: “There is no obstinacy like that of a sheep asked to move from its last corner of pasture, of a guest asked to go when a drink is still in the bottle, of a woman asked to remove one remaining garment, or a politician to forego one remaining principle.”

Muggeridge wrote little during the war years, partly because his activities as a spy—he worked for MI6, the English equivalent of the CIA, as did his friend Graham Greene—required total secrecy, partly because his spirits were low. Even his diary (which he called The Diary of a Sad Man) received sporadic attention. He wrote to Kitty in 1942: “Much of the time I spend wishing I was dead, wondering why I am doing what I have to do, putting up my own faint struggle with the tedium of time.”

After the war, Muggeridge edited an English version of the secret diaries and wartime papers of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law. The papers had been smuggled out of death cell 27 in the Verona jail just prior to Ciano’s execution in 1944. “What Ciano achieved,” Muggeridge wrote, “was to provide the world with one more record, incomparable in its naiveté, of how futile a pursuit is power, and how certainly those who pursue it become enmeshed in their own deceits and stratagems.”

In 1946, Muggeridge came to America as Washington correspondent for the Daily Telegraph. “Americans,” he wrote back to Kitty, “are the most terrible bores the world holds; they only really want to talk about themselves and that’s a soon exhausted subject.” Even his routine American journalism contains prescient nuggets, and surely his succinct description of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles has not been bettered: “Dull, duller, dulles.”

When the US air force carried out its hydrogen bomb test on the island of Bikini, Muggeridge described the whole operation to Kitty as “inimitable”: “The airplane that carried it was called Dave’s Dream and a pin-up girl was painted on the bomb before it was dropped. Apparently scarcely any damage was done at all. A flock of goats left on the island appeared unperturbed afterwards.” Later, Muggeridge learned that the pin-up girl on the bomb was Rita Hayworth, and that she had wept on learning of this honor.

When the Bikini goats, together with a handful of Bikini rats, were brought back to the United States for observation, Muggeridge went along to see them, and concluded his account for Kitty’s delectation: “They were all receiving blood transfusions and vitamins in air-conditioned pens. A press handout answering criticism of humane societies that it was cruel to submit animals to atomic explosions contained the delightful phrase: ‘They have not died in vain’. I suggested that there be a tomb erected to the unknown pig on which visiting statesmen might lay a handful of acorns.”

A Minefield

Back in England, Muggeridge was promoted to deputy editor at The Daily Telegraph; then, in 1953, the first editor of Punch from outside the magazine’s staff in that venerable British magazine’s long history. He quickly transformed the staid old lady of the doctor’s waiting room into a fiercely satirical journal, “a minefield over which the eminent must tread at their peril.” An article from his first year, “How to Be a Successful British Diplomat,” illustrated Punch’s new bite:

(1) When an international agreement is unilaterally denounced, insure that any formal protests you are instructed to make are as hesitant and equivocal as possible; (2) Remember that nowadays the glittering prizes are given for feats of demolition, not of construction. . . . Every diplomat carries a peerage in his knapsack, provided only that he keeps retreating; (3) Do not allow seeming setbacks to lower your spirits. Rather, they should be made the occasion for displaying even more complacency and self-satisfaction than before; (4) In politics, incline to the left. If you can combine this with ample private means . . . so much the better; (5) No opportunity should be missed of taking a sly dig at Americans and their policies. Indeed potential allies everywhere should be treated as somewhat ludicrous if not downright despicable.

In February 1954 a Punch cartoon depicting a paralytic Prime Minister Winston Churchill touched off a terrific row, as the British public had not yet been informed that Churchill had suffered a stroke. The ensuing hue and cry very nearly cost Muggeridge his job; when, at the crest of the storm, he took a swipe at Foreign Minister Anthony Eden (“Better a Churchill senile than an Eden in full possession of his faculties, such as they are”), he gave fresh offense to both camps.

But nothing in Muggeridge’s controversial journalistic career rivaled his “Royal Soap Opera,” which appeared in the Saturday Evening Post on October 19, 1957. The theme was that materialist societies like ours are especially prone to hero-worship; having largely ceased to believe in God, they pay increasing obeisance to a queen or royal family, making of a symbol (“no bad thing in itself”) a kind of substitute or ersatz religion.

The Queen happened to be touring America when the article appeared (it had been written nearly two years before), and the British press smelled blood. Muggeridge’s article was described as treasonous, ruthless, shocking, patronizing, and gruesome, to quote only a few epithets. He received death threats and his home was vandalized. As he walked along the seafront in Brighton, a passer-by spat in his face. He was banned from the BBC, and his newspaper column was dropped.

We who have lived to watch the authority of the monarchy reduced to a ribald joke—soap opera indeed—can but marvel at Muggeridge’s prescience and courage. If even he could not have imagined someone quite like Princess Di, he could nevertheless say, paraphrasing Kipling, “I saw the sunset ere most men saw the dawn.”

The Street-Walker

In the 1960s and 1970s Muggeridge operated as a sort of freelance world correspondent; as he put it, he had taken up the hazards of street-walking in preference to the security, such as it was, of being an inmate of a licensed house. He wrote for papers and magazines in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia, and elsewhere. His television programs were broadcast throughout the English-speaking world. Even to summarize his utterances in this hectic period is to shortchange his prophetic gifts. Nevertheless, here, without comment, are a few delicious Muggeridgisms:

• “Pleasure is but a mirage of happiness—a false vision of shade and refreshment seen across parched sand. Where, then, does happiness lie? In forgetfulness, not indulgence, of the self. In escape from sensual appetites, not in their satisfaction. We live in a dark, self-enclosed prison which is all we see or know if our glance is fixed ever downwards. To lift it upwards, become aware of the wide, luminous universe outside—this alone is happiness.” (1965)

• “You can leave two computers in a room by themselves without the slightest anxiety.” (1969)

• “The twentieth century’s version of Descartes’ famous dictum is, ‘I screw, therefore I am.’” (1969)

• “Man is a fugitive from reality who must somehow be persuaded to confront his own imperfection and despair.” (1976)

• “The most highly educated society in Western Europe elected Hitler and the highest density of Universities per acre and per person is to be found in California. Need I say more?” (1978)

• “There is no such thing as darkness; only a failure to see.” (1979)

• “A key to our present discontents is simply that the burden of being free has come to seem too heavy to be borne, and that, consciously or unconsciously, willfully or under duress, the prevailing disposition is to lay it down. In a famous scene in Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov, the Chief Inquisitor turns away the returned Christ because he brings with him the dreaded gift of freedom. Governments, as it seems to me, whatever their ideology, are going to show themselves of a like mind with the Grand Inquisitor.” (1978)

After the South African Christian Barnard performed the world’s first heart transplant surgery in December 1967, Muggeridge asked him (on a BBC television program with the risible title, “Dr. Barnard Faces His Critics”) whether such experimental surgery was first performed in South Africa because facilities there so outpaced the rest of the medical world, or because the vile doctrine of apartheid had so devalued human life that it had conditioned Dr. Barnard and people like him to regard human beings as spare parts for medical experimentation. It was a shrewd question, albeit it caused consternation all around. Dr. Barnard’s soi disant “critics” on the BBC panel immediately distanced themselves from Muggeridge’s question, urging Barnard not to dignify it with an answer—which he didn’t.

To Do with Eternity

This episode marked the beginning of Muggeridge’s emergence as a relentless opponent of medical hubris: in abortion, euthanasia, genetic engineering, etc. Two decades before the existence of a worldwide black market in human organs was admitted to, Muggeridge had not only predicted its emergence but had also detailed the economies of its operation and just how it would work.

When Pope Paul VI issued his controversial encyclical Humanae Vitae in 1968, Muggeridge wrote a supportive letter to The Times: “May I be permitted, as a non-Roman Catholic and only dubious Christian, to pay a tribute to the Pope’s noble statement on birth control. . . . I do not doubt that in the history books, when our squalid moral decline is recounted, with the final breakdown in law and order that must follow (for without a moral order, there can be no order) the Pope’s courageous and just, though I fear in the event largely ineffectual, stand will be accorded the respect and admiration it deserves.”

Four years after he wrote those words, Muggeridge was received into the Roman Catholic Church. This event, in the ordinary course private, generated headlines in the British press. In The Times, Muggeridge wrote:

It might seem rather absurd for someone like myself well into his 80th year to be seeking admission to a particular church—in my case, the Roman Catholic church. Like taking out a life insurance policy when one’s life is almost at an end. Yet since membership of a church is to do with eternity rather than time, years are scarcely a consideration. After all, babies are baptized before they can understand the significance of baptism, so why should not octogenarians be received into a church shortly before leaving it in a coffin?

On what might broadly be called “life” issues, there are too many examples of Muggeridge’s prophetic insight to quote even a representative sample; I content myself with this one comment (from The Observer in 1966), admittedly in Muggeridge’s hyperbolic mode, but daily, it seems to me, coming to pass: “By the time men are finally delivered from disease and decay—all pasteurized, their genes counted and rearranged, fitted with new replaceable plastic organs, able to eat, copulate, and perform other physical functions innocuously and hygienically as and when desired—they will all be mad, and the world one huge psychiatric ward.”

Death was a topic about which Malcolm frequently thought and wrote. At the age of 76, he wrote this: “Like a prisoner awaiting his release, like a schoolboy when the end of term is near, like a migrant bird ready to fly south. . . . I long to be gone. Extricating myself from the flesh I have too long inhabited, hearing the key turn in the lock of time so that the great doors of eternity swing open, disengaging my tired mind from its interminable conundrums, and my tired ego from its wearisome insistencies. Such is the prospect of death.”

An Apt Epitaph

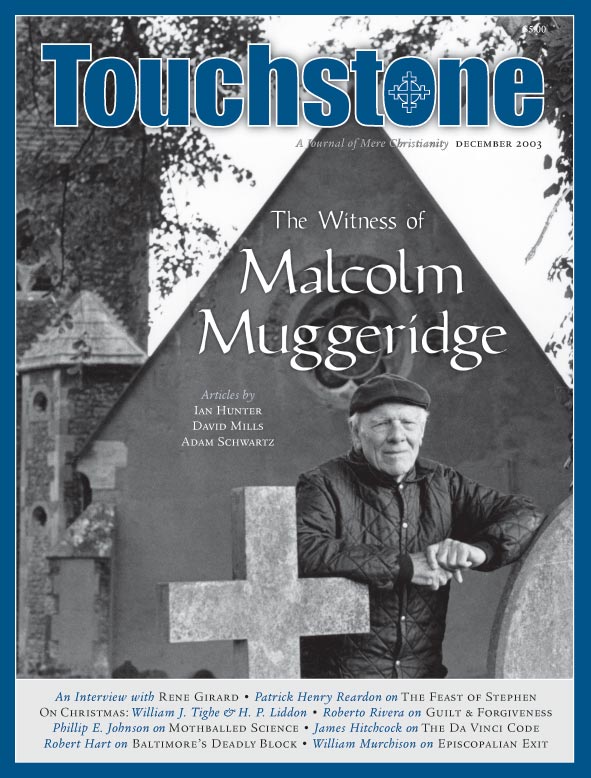

Alas, Malcolm’s death was not to be the easeful passage from time to eternity that he had hoped for; his mind disintegrated, he grew suspicious and quarrelsome, at the last he was confined to a nursing home. He died on November 14, 1990, at the age of 87. He was buried in the village cemetery at Whatlington in Sussex, and on his gravestone the epitaph is “Valiant for Truth.” It is an apt inscription, for, though at the end his mind may have been troubled, this contemporary prophet had earned the right to echo the words of Bunyan’s Mr. Valiant-for-Truth:

“Though with great difficulty I am got hither, yet now I do not repent me of all the trouble I have been at to arrive at where I am. My sword I give to him that shall succeed me in my pilgrimage, and my courage and skill to him that can get it. My marks and scars I carry with me, to be a witness for me, that I have fought his battles who will now be my rewarder.” . . .

And so he passed over, and all the trumpets sounded for him on the other side.

Ian Hunter is Professor Emeritus in the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario. He is the author of biographies of Robert Burns, Hesketh Pearson, and Malcolm Muggeridge.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

28.2—March/April 2015

Man, Woman & the Mystery of Christ

An Evangelical Protestant Perspective by Russell D. Moore

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor