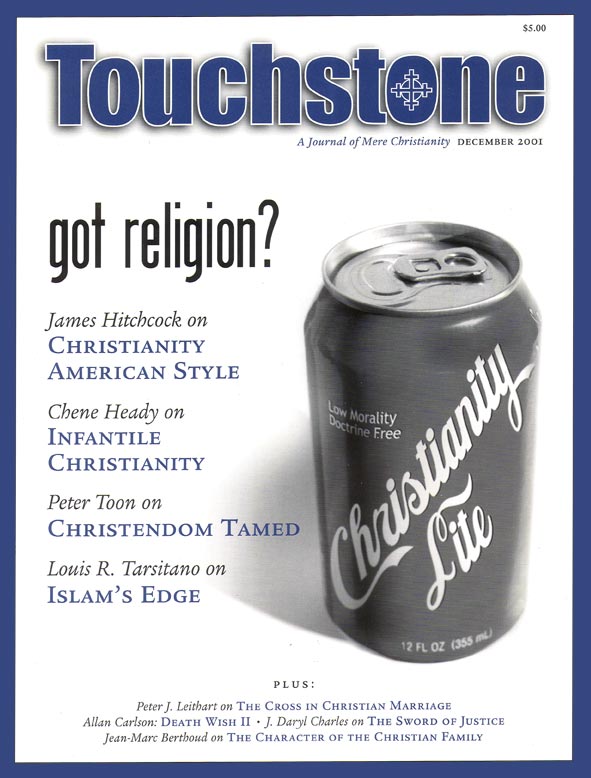

Christianity American Style

The United States is by all measurable standards one of the most religious nations in the Western world, a finding surprising because in many ways it runs counter to almost everyone’s experience of a secular culture in which the claims of Christianity seem not even to be respected, much less heeded, in which religious influence seems to be on the wane. But in different ways both opinion polls and unsystematic experience are probably accurate.

Despite the buffetings traditional religion regularly receives, belief remains remarkably tenacious in America, and all claims that it is an atavistic and dying phenomenon have now been discredited. Indeed, the United States seems to be the great exception to the prevalent thesis that industrialization and urbanization always result in secularization.

The sources of this hardy religiosity are in some ways obscure, but from the very beginning of the country serious religious faith was part of the basic fabric of the culture, and religious ways of looking at reality have always come readily to the American mind, the Second Great Awakening after 1800 being the crucial instance.

In all opinion polls, Catholics show themselves to be more orthodox than liberal Protestants but less so than Evangelical Protestants, even extending to such questions as belief in God or in life after death. Catholics seem to have been harder hit by the corrosive secularism of the culture than have their Evangelical brethren.

Perhaps consistency ought not to be expected from mere human beings, but the apparent vitality of American Christianity raises alarms when popular beliefs are scrutinized. Thus, in one survey Christian adolescents ranked Jesus fifth on their list of most admired persons, after Lincoln, Washington, John F. Kennedy, and Martin Luther King, Jr., although Jesus did rank five places above Elvis Presley. Over 90 percent of Christians in Minnesota, according to one detailed ecumenical survey, believe in life after death, but only 69 percent think Jesus himself rose from the dead. American Christians have a measurably poorer knowledge of the Bible than did those of a generation ago.

While there are many forces in modern culture that are obviously hostile to orthodox religion, as far as popular faith is concerned, it seems that mere rationalism is not one of them. On the contrary, American Christians are often guilty of an excess of credulity, even of superstition. Thus, a quarter of all Catholics reportedly believe in reincarnation (once again, a higher percentage than among Protestants), while among adolescents over half believe in astrology, and more than a fourth in witchcraft.

The key to understanding all this is the hardly surprising fact that 71 percent of people believe in heaven, but only 53 percent believe in hell (the latter figure in fact surprisingly high). The orthodox belief that human beings survive after death is warmly accepted by believers primarily insofar as it promises personal happiness, not insofar as it threatens punishment. Despite their conviction that they will enjoy eternal life, about half of Christians disbelieve in the Last Judgment.

Over three-quarters of Christians say that they do not fear God, and the same proportion think he intervenes in their personal lives, but only in very “positive” and “supportive” ways. Spontaneous descriptions of God are varied—somewhat less than half of all believers see him as “master,” about a third as judge, creator, or redeemer, a fourth as friend, and a low proportion as father, mother, or liberator.

Given that the central teaching of the gospel is redemption from sin, perhaps the most significant index of the true state of American Christianity is that only about half of all believers think that they themselves are sinners, with the others preferring to say that they merely “err.” Only about half of Christians even think it is necessary to believe that human beings in general sin.

Three-quarters of all Christians think that people should arrive at their own beliefs independent of any religion. Asked to identify those things most important for the followers of Jesus, only half of American Christians named the Ten Commandments, and ten percent said “social justice,” whereas over three-quarters found that belief in Jesus increases one’s self-esteem. Somewhat over two-thirds of young Catholics say that doing God’s will is important, but they rank it the eleventh of seventeen values, lower than health, self-fulfillment, and education.

The obvious consistency in patterns of belief is that Americans tend to value religion insofar as they regard it as supportive of their personal lives but not when it seems to “interfere” in their lives and make demands on them. They are deeply religious in a sense, but their commitment proves fragile when it fails to provide the emotional support they seek. Not surprisingly, between 1950 and 1990 the proportion of Americans saying that religion was “very important” declined from 83 percent to barely half.

Predictably, sexual morality is the area that shows the most striking divergence between orthodox teaching and many of the people in the pews. A study of Minnesota Christians finds, for example, that 85 percent accept divorce, 60 percent abortion, 36 percent premarital sex, and 39 percent homosexuality. (They are family-oriented in that only 15 percent approve extramarital sex.)

Although Christianity has often been accused of overemphasizing sexual morality, sexuality is so deep a part of each person’s being as to shape personal identity profoundly. Thus, a Christian who lives according to worldly sexual standards is abandoning Christian teaching at precisely the point where it ought to penetrate the deepest parts of his psyche. Sex is the chief way in which modern culture now asserts the autonomy of the self, its rejection of all “imposed” restraints on self-expression.

The deficiencies of lived faith tend to be magnified among the young. Not only are they suffering from the inability of the churches to inculcate orthodox beliefs effectively, often they suffer also from the ambivalences of their own parents, so that the family, far from being a bulwark of faith, becomes a further obstacle to it. Over half of young Catholics (40 percent of young Protestants) say that religion is less important to them than it is for their parents.

Many young Christians leave the church at some point in their lives, and those who return commonly offer as their reason an ill-defined “inner need.” College students express an increased “interest” in religion, while at the same time their level of belief and practice tends to decline.

The very religiosity of American culture is often turned against Christianity, in that the entire world has now been made to seem like a spiritual garden in which people can browse as they see fit, plucking the flowers that smell fragrant. Plucking them does not require accepting the church’s discipline—literally becoming a disciple—but merely savoring the scent and leaving the rest. The ultimate test of religious authenticity is now thought to be personal feelings, which are among the few things the culture still regards as sacred. Religion has value insofar as it makes the individual feel good. But in some respects this is a more dangerous condition than outright skepticism, since it enables people who are actually pagans to think of themselves as devout.

Quite obviously, the Church today must be counter-cultural, in that some of the dominant forces in the culture are blatantly anti-Christian. Vital faiths in effect create their own “plausibility structures,” which in some ways are even more real to their members than are the influences of the larger culture. But to be unwaveringly counter-cultural automatically places the Church on the margins of society and immediately deprives it of plausibility in the eyes of the many people whose mental world is entirely defined by conventional opinion.

The attempt to adapt religion to the culture is ultimately unsuccessful because religiously liberal people soon learn to dispense with the Church altogether. The most obvious measurable difference between church members and non-church members is over sexual morality, which is itself a leading cause of defections from the Church.

If the Church proclaims an unambiguously orthodox message, it immediately offends even some within its own fold, but to soften its teachings to assuage such people is in the end even more destructive of religious vitality. Meaningful evangelization can only take place among those who have not wholly enshrined their own wills as the ultimate test of truth.

Just as most Americans seem to want a reduction in government spending without a reduction in government services, so also they want a stable moral order that does not impinge on their own freedom, as they define it. Americans seek in religion a sense of certainty as an alternative to the prevailing skepticism and a sense of community as an alternative to the prevailing individualism, but they are less than fully willing to pay whatever personal price may be required of them.

Converts often tend to be more orthodox and more committed than many born Christians, showing that people are attracted to the Church precisely because of its clear teachings and apparently strong discipline.

Although Christianity has always appealed to people emotionally on many levels, at its best it has always offered itself to the world in terms of profound doctrine, formal worship, and coherent morality. But classical evangelization may be effective only within a disciplined, cohesive society, in which the legitimacy of structures is itself accepted. Since the l960s such has not been the nature of the Western world.

The credulity of many Americans with regard to things supernatural indicates a deep spiritual longing, which the liberal churches have radically misunderstood. In many cases the clergy themselves are the direct agents of skepticism, dampening the spontaneous religious ardor of their flocks.

Thus, effective evangelization today must focus on the individual and his spiritual needs, learning how to touch the emotions at the proper places, then channel those emotions towards their appropriate object. The danger of such an approach is that it will stall at the level of personal religious feelings and that would-be converts will remain faithful only insofar as their faith remains personally gratifying, not understanding how even spiritual gratification may be incompatible with true discipleship. Effective evangelization must gamble that often what people think they want is not what they truly want and that they can be made aware of that paradox. Subjective means must be used to bring people to objective truth, the great evangelical challenge illustrated in the classic principle of Ignatius Loyola—enter by the other man’s door, lead him out through yours.

—James Hitchcock, for the editors

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor