Mary Tyler Moore’s Autograph & What I Did with It

Russell E. Saltzman on Stem Cell Research

I got on the elevator in the Hart Senate Office Building heading for the second-floor hearing room, where I was to testify on embryonic stem cell research before a Senate subcommittee. I was there at the request of the National Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Secretariat for Pro-Life Activities. The door was closing but, at the last moment, in rushed Mary Tyler Moore, her husband, her publicist and a couple of other people with her. She was there to testify on the same topic as I, along with Michael J. Fox and several others.

One doesn’t expect to see a Hollywood celebrity in an ordinary elevator. It was a second or two before full recognition kicked in, and then, pow! I knew this woman. Gee whiz, I had had a crush on her twice, once when she was Laura Petrie and again when she was Mary Richards.

She’s never been more than thirteen years older than me, a fact I scoped out when I was sixteen. I can dismiss a sixteen-year-old’s crush, but when she was at WJM I was older and the crush was, well, more sophisticated. Now she’s standing this close to me. I tried to smile at her, but I think my mouth hanging open got in the way.

Following them out of the elevator I put myself right behind Moore, feeling like a stalker. My college daughter wanted Moore’s autograph, and I was going to get it. If I was going to speak to her, it had to be now. I called her name; she stopped. I introduced myself, told her I was testifying also, but in opposition, and would she please give me her autograph for my daughter Elizabeth.

“Only,” she joked, “if you promise to change your testimony.” But she gladly took the paper in my hand, cheerfully signed it “To Elizabeth with best wishes.” Above the i in wishes she drew a little heart, just as Mary Richards would have done.

Embryos Going to Waste

The September 14 hearings were before the Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education—congressional committee titles are topical catch basins—chaired by Sen. Arlen Specter (R-Pennsylvania). The ranking minority member is Sen. Tom Harkin (D-Iowa).

The two senators are urging legislation to allow the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to use taxpayer funds to acquire and destroy human embryos for the purposes of stem cell research. Present law allows the NIH to make grants for research on embryonic stem cells, but only, in a bookkeeping sleight-of-hand arrangement, if private funds are used to destroy the embryo and extract the cells.

Under the Specter/Harkin bill, the NIH could spend federal money to secure (no one is saying “purchase”) a steady supply of human embryos that could be destroyed (no one is saying “killed”) under direct NIH auspices. The embryos in question—estimates suggest there are from 100,000 to 150,000—are “leftovers” from fertility clinics, by-products of in-vitro fertilization (INF) attempts.

INF therapy may be a boon to childless couples who can afford the procedure, which often requires multiple attempts, but it has left us with awful questions of what to do with all the extra embryos. For Harkin and Specter and the NIH, these embryos are just going to waste. If they can save some lives, so it is argued, it’s better to use ’em than lose ’em.

Stem cells, so it is alleged, offer a potential cure for an array of ailments. They are undifferentiated cells that can, in theory, become any human cell you would ever want or need. Grow those little things forward so they differentiate into healthy organ and nerve cells, and Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (Lou Gehrig’s disease)—the list is fairly endless—will all become but distant memories in one of the greatest medical advances of the new century.

It swiftly becomes a problematic business, though, when the research focuses on human embryos as the source for this potential achievement. We are talking now of “leftovers” that are going to “waste.” Soon we shall be speaking of producing and destroying embryos explicitly for research. The “slippery slope” is slippery for a reason.

The issue becomes distinctly problematic when ample evidence points to other stem cell sources that are readily available for exactly the same kind of investigations. Umbilical cord blood and human placentas are rich in stem cells and offer as much or more availability as human embryos, and do so entirely without any moral objection. For that matter, clinical trials with adult stem cells extracted from a patient’s own bone marrow are perhaps a mere two to three years away, according to a researcher’s testimony before the subcommittee.

There is no evidence to suggest that trials with embryonic stem cells are nearly that close. Yet there is an unseemly haste to employ a means that, by itself, carries with it the greatest ethical objections imaginable.

The prospect of stem cell therapy derived from human embryonic research—involving the destruction of a human embryo—touches me, as a diabetic, in a most profound way. I would never consent to any treatment for my diabetes that directly or indirectly came about as the result of destroying a human embryo.

What I find disturbing about this incessant rush to harvest stem cells from embryos is the fact that no researcher to date has been able to develop a pancreatic cell from the techniques presently used, this while there are several promising avenues of research that do not involve destruction of a human embryo. Most recently, I have learned about investigations by Canadian researchers that employed pancreatic islet cells from cadavers.

The technique successfully eliminated the insulin-dependence of several diabetics who received the procedure. The procedure is subject to further trials, and it must be nuanced in application. But this holds greater promise for a diabetic cure than anything else I have heard about—and islet cell transplant is ethically neutral. It has no moral implications associated with it.

Yet, we here in the United States seem in a rush to use what is arguably the most ethically objectionable method available, while other morally neutral medical technologies virtually are at hand. The president’s own National Bioethics Advisory Commission has said that because human embryos deserve respect as a developing form of human life, destroying them “is justifiable only if no less morally problematic alternatives are available for advancing research.” The fact is, those alternatives exist.

The Representative Opponent

The hearings produced a little press flurry for me. The presence of Hollywood people, like Moore and Fox, brought out reporters and cameras. Though I was one of three opponents who testified, the news accounts from the Associated Press and CNN made me the representative opponent and in general pitted my remarks against those of Moore and Fox. In all, the hearing featured six supporters of the Specter/Harkin bill and three opponents.

My remarks were those most quoted after Moore and Fox, a diabetic and a Parkinson’s patient, respectively. The original AP wire coverage did note about three-quarters into the story that I, too, am diabetic, a potential beneficiary of stem cell therapy. Unfortunately, many of the edited versions that appeared around the country failed to report that small fact, nor was it mentioned in the CNN coverage. No coverage, except the Kansas City Star, mentioned my conception by step-siblings, something that would make me a prime candidate for a post-1972 abortion, a biographical fact I stressed to the senators.

More disappointing, very little of the coverage I’ve seen went into any depth regarding research alternatives presently available that do not entail destroying embryos for their stem cells. Yeah, I know. Like we should be surprised the media didn’t get it quite right?

During the exchange with me, Harkin was polite, Specter visibly testy. These embryos, Specter tells me, are leftovers, unwanted. What should we do with them, he demands? Besides, “They weren’t made like the rest of us, with a wife and a husband.” Well, duh, neither was I. But if I followed him rightly, extraordinary conception means we are free to treat the embryo as we want, especially so since it wasn’t made with a husband and a wife like the rest of us.

It was in some ways a shattering experience, but I understand Specter’s need to make his case. What, after all, do you do with a guy who, in the normal course of events today, would have been, should have been, aborted? If the embryonic me were available, would he want to do a slice-and-dice? Specter spoke of human embryos not as human life, but “potential human life.” Given his way, they wouldn’t even be that.

Following my testimony Moore and Fox came in, and I slipped out of the hearing room for a while. I needed a breath of fresh air. Well, bad air; I smoked a cigar outside. I returned in time to hear Mary Tyler Moore’s assertion that an embryo “bears as much resemblance to a human being as a goldfish.”

Helping her illustrate her point, Harkin later put a pencil dot on a piece of paper. That, he explained, is the size of an embryo. I was thinking, Harkin himself is a pretty tiny dot in the universe, cosmologically speaking. Does that lessen his essential humanity? And I know people who are uglier than goldfish. May we use them for our experiments?

Harkin has pulled out his dot-on-paper visual aid before, but never with opponents, always with supporters. Richard John Neuhaus, when told that an embryo or a very small fetus does not look like a human being, always notes, “That is exactly what a human being looks like when it is two weeks or two months old. It is what you looked like and what I looked like. It is what Jesus looked like inside his mother.”

Defining What a Human Being Is

I want to think that Moore and Fox are only misguided in their approach to a search for cures. I want to think that Specter and Harkin both are equally out to help people facing terrible ailments. Yet I came away from the hearing convinced that the question really isn’t over research. It isn’t about the best or fastest or surest means of bringing the promise of stem cells to the clinic, because better, faster, surer means exist.

Instead, the arrow of abortion pierces the heart of this issue, pierces it through—that and the philosophy of human autonomy. If we ever once admit that the human embryo carries any intrinsic value simply by virtue of its being human, even merely as “potential” life, then something must be said for all human life whatever its condition or stage of development. Yet we have somewhere, somehow, slipped into this notion of autonomy as defining what a human being really is, and we have a working definition: Human is as human does.

People who can do things like the rest of us do, people who live their “potential,” they are the real humans. A human being is someone who has full volitional will and mobility, someone able to choose his own destiny, seize control of his own life, and make choices for himself. A pencil dot can’t. Something the size of a pencil dot fails to qualify.

Which is why Harkin and Specter and Moore and Fox and the NIH feel free to make the choices for those who cannot choose. And no one even pretends that the decisions they will make are in the best interests of the human embryos in question. Quite the contrary. These embryos are there and they can help us, if they are first killed. So for “our” good they will be destroyed.

It comes to a question. Is the human embryo human life, or is it a mere bit of research material? If it is mere research material, then why should any human life at any stage of development—yours or mine—carry any special privilege? But if the embryo is human life, then we should have in place some restraint that cautions the strong against using the weak for their own purposes.

Two asides. First, it is not so certain that the embryos are unwanted. There are proposals that would allow infertile couples to adopt embryos for implantation. With the consent of original donors, some fertility clinics are making “spare” embryos available for just that purpose. Second, the Specter bill failed. Late in September Specter conceded he did not have the procedural votes necessary to end debate and bring the bill to the floor.

I left the hearing with Moore’s autograph tucked away safely in my briefcase. What she signed, though she doesn’t know it, was a copy of my testimony. And my daughter Elizabeth—the college sophomore who is able to major in psychology because when I was conceived the law forbade killing me in the womb—was delighted with the irony.

Russell E. Saltzman is pastor of Ruskin Heights Lutheran Church in Kansas City, Missouri, and the editor of The Forum Letter. “Mary Tyler Moore’s Autograph” is reprinted with permission from The Forum Letter, where an earlier version appeared. The quote from Richard John Neuhaus is taken from his Death on a Friday Afternoon.

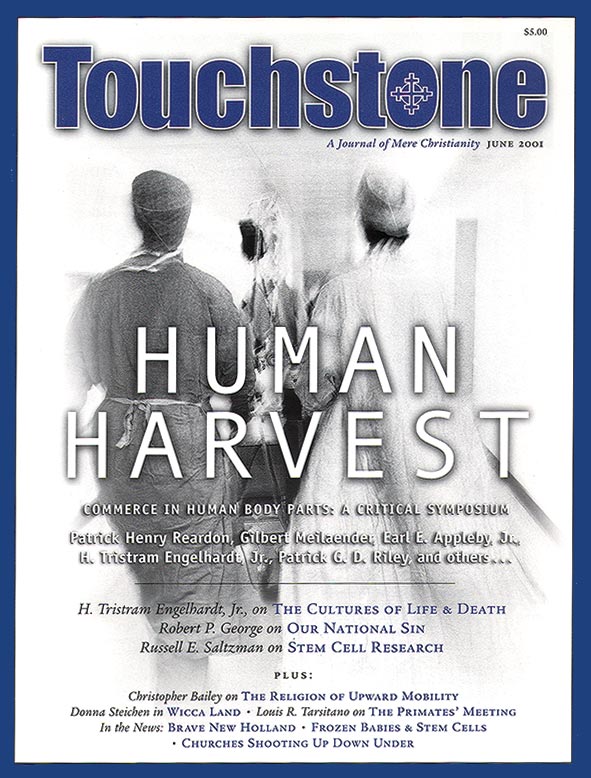

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on abortion from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor