The Humble Artist

The Christian Imagination: G. K. Chesterton on the Arts

by Thomas Peters

San Francisco: Ignatius, 2000

(157 pages; $12.95, paper)

by Eric Scheske

In one of his most popular books, What’s Wrong with the World, G. K. Chesterton wrote: “The average man cannot cut clay into the shape of a man; but he can cut earth into the shape of a garden; and though he arranges it with red geraniums and blue potatoes in alternate straight lines, he is still an artist; because he has chosen.”

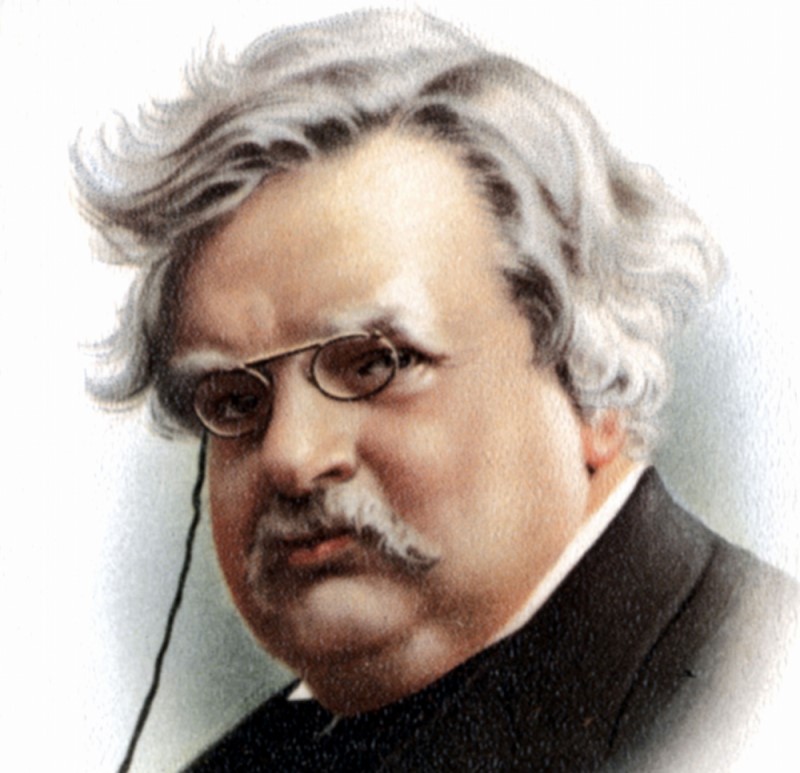

Chesterton was a giant of an artist, but more importantly, he was a giant of a man who understood what it meant to be a man: a creature made in God’s image, but still only a creature; a wonderful being made to wonder; greatness made to be humble. Those apparently inconsistent traits, Chesterton knew, are combined in every man.

These paradoxes are explained in Thomas Peters’s enjoyable new book, which shows both how they combined harmoniously in Chesterton himself and how they combined in Chesterton’s views on art. Because everyone is meant, at some level, to be an artist, the book speaks to all of us, regardless of our artistic level.

Peters starts with a clear picture of Chesterton. Chesterton, Peters tells us on the first page, was “a brilliant and entertaining Christian apologist and a fierce defender of the faith,” but also “a frolicsome child of the great Creator.” He was trained as an artist, opting as a young man to attend the Slade School of Art instead of a university, but quickly became a journalist—then a poet, a novelist, a public philosopher, and a Christian apologist.

Chesterton combined, in strong degrees, the paradoxical traits described above. Although he was extremely prolific—a writer whose nearly 100 books and thousands of essays touched almost every topic under the sun, from religion to politics to economics—he was down-to-earth. He would prefer to sit in a pub swilling beer to discussing religion and philosophy (though he relished the latter, too).

Fittingly, Chesterton’s artistic endeavors ranged from the lighthearted to the serious. His lighter artistic endeavors included “rowdy songs, drinking songs, and fighting songs,” little poems, and stories. Peters gives examples of all of them, but shows that Chesterton’s lighter endeavors often carried a heavy point.

Even something as seemingly inconsequential as men singing in a tavern was an important topic to Chesterton, especially if someone was trying to eliminate it. “Once men sang together round a table in chorus; now one man sings alone, for the absurd reason that he can sing better. If scientific civilization goes on . . . only one man will laugh, because he can laugh better than the rest.”

This combination of lightness and heaviness pops up throughout the book. Chesterton, for instance, was an accomplished sketcher, and Peters shows us five samples of his works—all cartoons. One drawing accompanies a poem about sailors who try to give an ungrateful fish humanly comforts. The fish, being only a fish, is ungrateful, so the sailors put him on trial, and Chesterton’s drawing shows an indignant fish being interrogated by an even more indignant sailor. This silliness, however, carried a serious message. It, Peters explains, “poked fun at the overzealous humanitarians who do more harm than good by seeking to help people who neither need nor want their help.”

Seriousness wrapped in frolic—this could be called the touchstone of Chesterton’s life. He approached heavy topics lightly and light topics seriously. If a person wanted to ignore (or trample upon) something minor and seemingly irrelevant, Chesterton would defend its importance. If a person wanted to be taken seriously, Chesterton would try to get him to lighten up, but he would always take the person’s issues seriously. In a way, his entire “serious frolic” approach is contained in his epistemology: “A man was meant to be doubtful about himself, but undoubting about the truth.”

His strong eye for truth is probably best evidenced in his essays, the thousands of newspaper articles that made him a household name in London toward the beginning of the century, starting with his first assignments for the Speaker (where he made his first of thousands of memorable quotes: “My country, right or wrong, is . . . like saying ‘my mother, drunk or sober’”). Chesterton would write columns for the Daily News (a column known as the “Saturday Pulpit”), Hilaire Belloc’s Eye Witness (though, in a show of his artistic bent, he primarily contributed ballads), G.K.’s Weekly (a newspaper he started in 1925 and continued until his death in 1936), and over 1,500 essays for the Illustrated London News.

It is interesting that Chesterton is perhaps best remembered for his essays and made his living by them, because he held them in low regard: “There are dark and morbid moods in which I am tempted to feel that Evil re-entered the world in the form of Essays.” Chesterton, Peters explains, thought the essayist wasn’t held to a standard and tended to be irresponsible because he didn’t come to a conclusion. Chesterton, however, always came to definite conclusions, which probably contributed to the popularity of his articles.

Though the book is foremost about Chesterton, it gives valuable insight into the artistic endeavor in general. Perhaps most importantly, the book explains what Chesterton always knew: that artistry, indeed any type of greatness, requires humility. Chesterton’s “most essential point,” says Peters, is that “true imagination—and most especially Christian imagination—is grounded solidly in the soil of humility. . . . Pride is directly inimical to creativity.”

Specifically, the artist needs the humility of the child, who is a natural artist because he has the sense of wonder that every artist needs. If a person thinks (as the modern adult tends to think) that he has it all figured out, he will fail to be entranced by God’s creation and will be unable either to see it properly or to describe it to others. The child and artist, on the other hand, fall to their knees in wonder at the smallest thing, seeing in everything something great and worthy of appreciation and wonder. It’s a very humble mindset, as Chesterton described when he wrote, “The only way to enjoy even a weed is to feel unworthy even of a weed.” The combination of humility and wonder, and their role in art, is the staple of this book.

This theme ripples throughout the book, such as in Peters’s recounting of Chesterton’s intellectual battles with the artistic “cutting edge” of his day. Chesterton, for instance, had little tolerance for the aesthete, of whom he wrote, “They have goaded and jaded their artistic feelings too much to enjoy anything simply beautiful . . . the definition of an aesthete is a man who is experienced enough to admire a good picture but not inexperienced enough to see it.” Chesterton disliked aesthetes because they are more concerned about looking like an artist than being an artist. “Chesterton insisted that real artists are ordinary people who do art; they are not finely tuned instruments hovering on the brink of psychological catastrophe. Nor do artists need to live in trendy places, to possess certain eccentric furnishings, to wear a certain arty kind of clothing, or to eat at notorious cafés.” This point alone makes the book worth the price, especially for the young or aspiring artist who tends to effect an arrogant or eccentric air—a miasma that can be seen in artistic circles at any local university today.

Chesterton likewise disliked the artistic temperament that found itself too superior to be understood by the common man. “G. K. was always rather impatient with esoterica, whether artistic or intellectual, as he saw it as a form of snobbery designed intentionally to exclude the common person. Here he was particularly concerned with the propensity of modern artists to portray themselves as too ‘deep’ to communicate with commoners.”

It is pride that Chesterton detested—and that was at the root of the art world’s cutting edge that he found himself opposing. Their “guiding principle,” Peters observes, is “the standard human desire to be considered as more important than other people.” Not only were they ruining art for everyone else, his opponents weren’t even properly considered artists themselves because “personal pride works to distract, deflect, corrupt, co-opt, frustrate, and even destroy our God-given capacities for imagination.”

These men were the social elite almost 100 years ago, so Chesterton’s criticism of them may seem somewhat out-dated and irrelevant. It’s not. For reasons beyond his control, he lost those battles at the larger level of Western civilization. Consequently, their ideas have today settled over society like smog where most everyone holds those foggy ideas as prima facie signs of clear thinking. Peters’s recounting is helpful for the man in the everyday world who necessarily encounters these attitudes everywhere—in the office, at cocktail parties, on television.

The book has many other virtues. Peters displays a thorough familiarity with Chesterton’s corpus of works, citing no less than two dozen different books and drawing on many of Chesterton’s lesser-known books, such as his first published book, Greybeards at Play (a collection of poems) and The Poet and the Lunatics (a novel). Throughout the book, Peters also gives insight into “sideline” issues. In his discussion about Chesterton’s delight in writing songs, for instance, he observes that Chesterton resisted the modern attempt to analyze separately sound and meaning, pointing out that in song they become inseparable. In Chesterton’s words, “sense depends on the sound and the sound depends on the sense. It actually would not sound the same, if another meaning were expressed by the same sound.” For proof of this, try singing the tune of Billy Joel’s “Piano Man” with Vietnam War protest lyrics, or singing the “Piano Man” lyrics to a country beat.

The book includes a good introductory biography of Chesterton. Unfortunately, for some reason the biography is placed at the end of the book instead of at the beginning. If a reader unacquainted with Chesterton buys the book, I suggest he read the last chapter first. The book also illustrates Chesterton’s approach to issues like materialism and empiricism and their relation to art, which is useful because Chesterton’s uniqueness often makes it difficult for the newcomer to understand him (Peters also explains some of Chesterton’s unique word choices; when Chesterton says “poet,” for instance, he means artist in the broad sense).

In his essay, “Why I Write,” George Orwell wrote, “One can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s personality.” His fellow Englishman, Chesterton, would have agreed. He was an intellectual and artistic giant, but he was humble, and it was his humility that paved the way for his giant success. “Humility,” Peters points out, “is literally the foundation for greatness.” We should all be so humble as Chesterton, especially since, like Chesterton, we are all meant to be artists, but, unlike Chesterton, we have achieved paltry little next to his mammoth greatness. •

Eric Scheske works as an attorney in Sturgis, Michigan, where he attends Holy Angels Catholic Church. In addition to Touchstone, his articles have appeared in New Oxford Review, Culture Wars, Lay Witness, The Catholic Faith, and Gilbert!

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on imagination from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor