The Century of the Cyclops by Steven Faulkner

Feature

The Century of the Cyclops

On the Loss of Poetry as Necessary Knowledge

by Steven Faulkner

Someone recently won a $75,000 poetry prize. I don’t recall the poet’s

name. The sponsors of the prize thought that big bucks would help revive interest

in poetry. The winner of the Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize for $25,000, Charles Wright,

admitted that this country’s interest in poetry is in something of a free

fall, but he hoped these large prizes would arrest that fall. I doubt it will

help.

Who reads modern poetry? A reporter for National Public Radio interviewed another

poet who said that people may no longer know why “The woods—are

lovely, dark and deep,” but they do understand the money message. If someone

forks out 75 big ones for poems, poems must be valuable property.

These are cries of desperation. One comes to love poetry as a man comes to love

a woman, by first catching her eye in passing, by stumbling through a few embarrassing

conversations with her, by listening to her, attending to her, getting caught

up in the mysteries of love. If someone offered us money to take an interest

in a woman, we would know that something was drastically wrong.

Like modern art, modern poetry began to lose its audience almost a century ago.

Indecipherable and egocentric, impressionistic poetry does not catch the eye,

much less bear listening to. The old standards of Beauty, such as clarity and

coherence, have fallen to the shifting winds of subjectivism, relativism, and

skepticism. What beauty remains has been stripped from reason, severed from

its old Platonic mates, the Good and the True. Our modern poetry is in pieces.

This makes a defense of poetry difficult. But defend it we must, for poetic

knowledge is an essential kind of knowledge. Without it, our understanding of

the world suffers a severe distortion. It is as if we have grown up in an age

of one-eyed men who have heard rumors that people could once judge distances,

depths, and colors by the use of two eyes, but are now reduced by this flat,

prosaic information age that relies on scientific analysis as virtually our

only source of knowledge. We are a century of Cyclops.

Poetry as a way of knowing is essential to the human being. Modern thinkers,

the heirs of Immanuel Kant, have come to depend almost entirely on discursive

reasoning, packing journals and academic books with complex analysis, deduction,

demonstration, abstraction, and argumentation. This is necessary in its place,

but it is not the only necessary knowledge.

Sir Philip Sidney, in his Defense of Poetry, written when Shakespeare

was young, said the poet “yieldeth to the powers of the mind an image

of that whereof the philosopher bestoweth but a wordish description, which doth

neither strike, pierce, nor possess the sight of the soul so much” as

poetry does.

Linear, rational discourse is the domain of philosophy and rhetoric. “The

philosopher teacheth,” said Sidney, “but he teacheth obscurely,

so as the learned only can understand him; that is he teacheth them that are

already taught. But the poet is the food for the tenderest stomachs; the poet

is indeed the right popular philosopher.” The reason for this is that

poetry appeals to the whole person, not merely to reason. Even the young and

the uneducated can appreciate it. Jacques Maritain wrote: “Poetry is the

fruit neither of the intellect alone, nor of imagination alone. Nay more, it

proceeds from the totality of man, sense, imagination, love, desire, instinct,

blood and spirit together.” Poetry can of course be highly intellectual,

demanding much from the mind, but it is always more than intellectual; it is

intuitive. It is a way of seeing and admiring the whole without taking it apart

by analysis. It is a taking into the self that which cannot be fully explained,

a way of observing with silent attention rather than active inquiry, what Wordsworth

called a “wise passivity,” or “passionate regard.”

This distinction between discursive knowledge and intuitive or poetic knowledge

is a very old idea. German philosopher Josef Pieper explains this at some length

in his book, Leisure, The Basis of Culture:

The Middle Ages drew a distinction between the understanding as ratio

and the understanding as intellectus. Ratio is the power

of discursive, logical thought, of searching and of examinations, of abstraction,

of definition and drawing conclusions. Intellectus, on the other

hand, is the name for the understanding in so far as it is the capacity of

simplex intuitus, of that simple vision to which truth offers itself like

a landscape to the eye. The faculty of mind, man’s knowledge, is both

things in one, according to antiquity and the Middle Ages, simultaneously

ratio and intellectus; and the process of knowing is the

action of the two together.

It is difficult to stress this point enough in this hardworking, scientific

age that seeks to dissect and define all mysteries, leaving no room, not even

a category, for the effortless awareness, the contemplative vision of the ancient

Hebrews, Greeks, and medieval Christians. The Hebrew poets who wrote great sections

of the Bible understood the necessity of contemplative knowledge. Thomas De

Quincey, in The Poetry of Pope, wrote of them:

The Scriptures themselves never condescended to deal by suggestion or cooperation

with the mere discursive understanding; when speaking of man in his intellectual

capacity, the Scriptures speak not of the understanding, but of “the

understanding heart”—making the heart, i.e., the great intuitive

(or non-discursive) organ to be the interchangeable formula for man in his

highest state of capacity for the infinite.

Thus the Psalms and prophets express more of a contemplative vision of God than

a view merely doctrinal or dogmatic. Certainly there is doctrine there, but

the truths of the Psalms and prophets are not expressed as systematic theology,

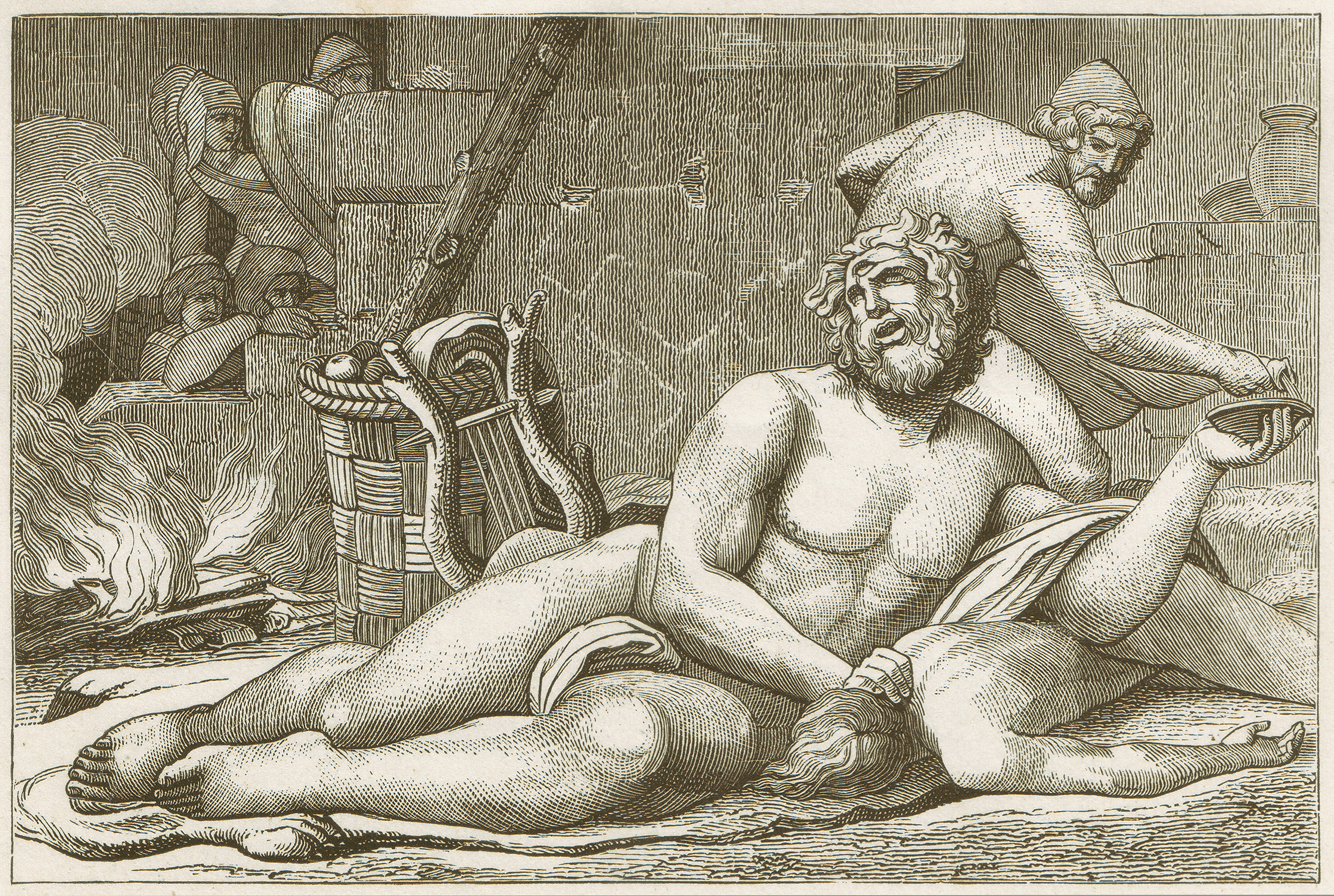

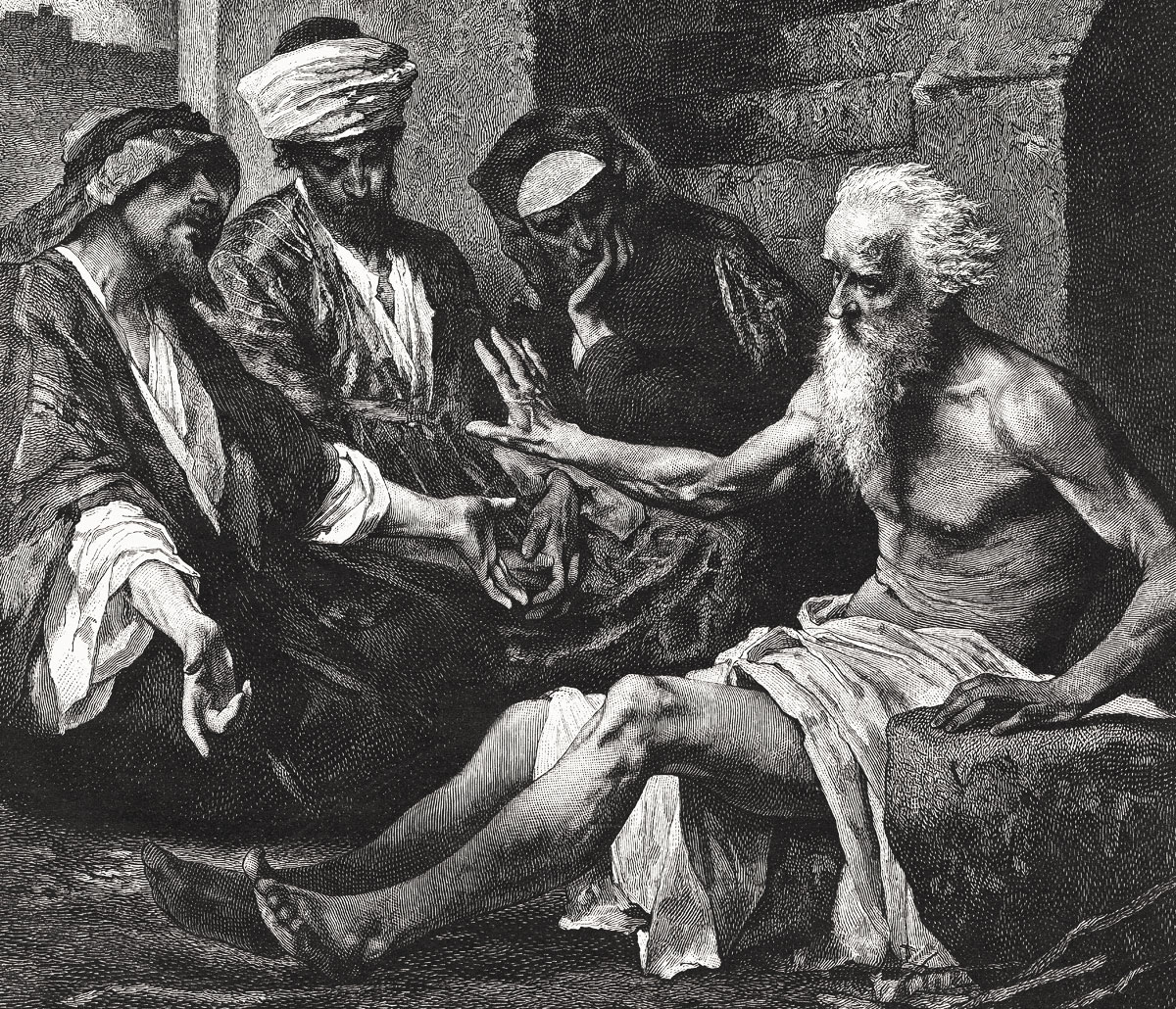

but as poetry. Job, overwhelmed with loss and suffering, asks God for a rational

explanation. He demands to know the reason for his afflictions. But God’s

answer is given in rich, ironic poetry:

Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind:

“Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Gird

up your loins like a man, I will question you, and you shall declare to me.

“Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me,

if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you

know! Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who

laid its cornerstone, when the morning stars sang together, and all the sons

of God shouted for joy?” (Job 38:1–7)

And so, for chapter after chapter, God speaks forth a landscape of great majesty

and beauty until Job says quite simply, “I lay my hand on my mouth. . . . I

had heard of thee by the hearing of the ear, but now my eye sees thee; therefore

I despise myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” This is the knowledge

that simply sees, that contemplates even the transcendence of God in the minutiae

of creation and somehow comprehends the incomprehensible.

This word comprehend is a good one. It means “to take in.”

This is knowledge by union, rather than knowledge by analysis. Analysis always

breaks the object of its inquiry in pieces in order to examine the constituent

parts. Examine the idea, the economic plan, the political policy, the piece

of vegetation, the animal, the machine, all in the same way. It is Descartes’s

methodology. Take it apart and put it back together again. But there is a knowledge

by union which, as Karl Stern says, is contrary to knowledge by disassembly:

Simple self-observation shows that there exist two modes of knowing. One

might be called “externalization,” in which the knowable is experienced

as an object, a Gegenstand, something which stands opposed to me;

the other might be called “internalization,” a form of knowledge

by sympathy, a “feeling with”—a union with the knowable.

Thomas Aquinas, often accused of being merely rationalistic, called this intuitive

kind of knowledge connatural knowledge: “The spiritual man knows divine

things through inclination and connaturality; not only because he has learned

them, but because he experiences them.” This is knowledge by participation.

We have an inherent relationship with all things in nature; we are co-natured

and thus our knowledge of such things is a kind of natural sympathy. Stern goes

on to quote Henri Bergson: “By intuition is meant the kind of intellectual

sympathy by which one places oneself within an object in order to coincide

with what is unique in it and consequently inexpressible. Analysis, on the contrary,

is the operation which reduces the object to elements already known, that is

to elements common both to it and other objects.” Dissecting analysis

produces the categorizing of commonalities; poetic intuition simply sees or

takes in what we can never fully define.

A horse, for example, is more than the sum of its parts. In Charles Dickens’s

novel Hard Times, a model student named Bitzer describes a horse in

this way: “Horse: Quadruped. Graminivorous. Forty teeth, namely twenty-four

grinders, four eye-teeth, and twelve incisive. Sheds coat in the spring in marshy

countries, sheds hoofs, too. Hoofs hard, but requiring to be shod with iron.

Age known by marks in mouth.” But this is not a horse; nothing but a list

of a horse’s parts. Better the warhorse in Job that “paws in the

valley, and exults in his strength. . . . With fierceness and rage he swallows

the ground.”

Poetic knowledge, as Sidney said, gives sight to the soul in a region of mysteries.

We cannot reduce everything we experience to precise definition. C. S.

Lewis noted this in an essay on language. He gave three examples of language:

1) It was very cold.

2) There were 13 degrees of frost.

3) “Ah, bitter chill it was!

The owl, for all his feathers was a-cold;

The hare limped trembling through the frozen grass,

And silent was the flock in wooly fold:

Numb’d were the Beadsman’s fingers.”

The first example is what Lewis calls ordinary language. The second, the scientific

description, gives a precise measure to the cold. The third is knowledge by

connaturality, by sympathy.

Where science seeks to master the knowledge of things with weights, measurements,

mathematics, statistics, poetic knowledge humbly understands the world as “vast,

immeasurable, impenetrable, inscrutable, mysterious,” to quote John Henry

Newman. Thus, says Newman, science results in system; poetry leads to admiration,

enthusiasm, devotion, and love. Science can be very useful; poetry is essential.

Wonder, humility, admiration, praise, gratitude, love—these are the

proper responses to poetic knowledge. The scientist seeks to understand and

control nature. But in doing so, as C. S. Lewis powerfully argued in The

Abolition of Man, humanity may lose its better self, for man’s conquest

of nature ultimately results in his conquest of himself. Lewis quotes Bunyan:

“It came burning hot into my mind, whatever he said and however he flattered,

when he got me to his house, he would sell me for a slave.” Science has

tried to reduce humanity to a complex, genetic machine. If anyone doubts this,

he should read Nobel Prize winner Francis Crick’s assessment of the human

soul as “no more than a vast assembly of nerve cells.” Crick thinks

he has identified the part of the mind where free will exists. But, of course,

if we are no more than a complex soup of nerves and chemicals, free will is

no longer free. Of such analysis is slavery made.

Mark Twain recognized that “scientific knowledge,” as useful as

it is, can actually deprive us of a greater vision. As a young, novice riverboat

captain on the great river, he describes a sunset: “There were graceful

curves, reflected images, woody heights, soft distances: and over the whole

scene, far and near, the dissolving lights drifted steadily.” His response

reveals he has seen poetically: “I stood like one bewitched. I drank it

in, in a speechless rapture. The world was new to me, and I had never seen anything

like this at home.” But years later, as an experienced captain, he had

learned the practical meaning of every ripple, every floating log, every variation

in color:

Now when I had mastered the language of the water, and had come to know

every trifling feature that bordered the great river as familiarly as I knew

the letters of the alphabet, I had made a valuable acquisition. But I had

lost something too. I had lost something which could never be restored to

me while I lived. All the grace, the beauty, the poetry, had gone out of the

majestic river!

Charles Darwin, near the end of his life felt the same way. He complained that

he no longer took pleasure in poetry or music, and little delight in scenery.

“My mind,” he said, “seems to have become a kind of machine

for grinding general laws out of a large collection of facts.”

Our schools teach almost only the scientific mode of knowing. We no longer teach

our children poetry, but we cram them full of numbers and definitions. Our academic

journals and journals of opinion are largely analytic. A hundred years ago,

journals commonly printed poetry, but now the public doesn’t know what

to do with a poem when one is printed. The culture has lost in a trice the wisdom

of millennia.

Poetic knowledge, connatural knowledge, intuitive knowledge, call it what you

will, plays an immense role in our lives: the child who laughs at his first

sight of a bee, the woman who weeps at her lover’s approach, the soldier

numbed by his friend’s sudden death cannot explain what they see. They

may later attempt some explanation of one facet or another of their experience.

They may attempt analysis, but the immediate experience in its totality is beyond

such dissection. The immediate awareness of a complex and mysterious reality

impresses not only the mind but also the emotions, the desires, and the memory.

Only poetry can sing of such things in any way commensurate with the immediate

experience, for poetry appeals to the whole man. And because the poetic experience

is not limited to linear thought, it hears countless echoes that correspond

to other experiences and other existent realities so that the mind and soul

naturally reach beyond the thing observed, listening intently toward the whole,

inquiring after the Source and Meaning of things. Again Maritain: “poetic

intuition makes things which it grasps diaphanous and alive, and populated with

infinite horizons. As grasped by poetic knowledge, things abound in significance

and swarm with meanings.”

But the culture and its intellectuals have thrown all of this into near oblivion;

we have lost sight of it, and, in doing so, we have lost an important way of

seeing. Blinded in one eye, we have lost the ability to admire, which means

to look upon with praising wonder. While we increase our mastery of the world

through science, we lose the vocation of the soul which is to see and contemplate

that which is around us as it leads to that which is beyond us. We must reclaim

its place in modern thought. We must recognize that poetic knowledge is not

mere sentimentality, but a real and necessary knowledge.

Steven Faulkner is a doctoral candidate in English at

the University of Kansas and resides in Topeka, Kansas, with his wife, Joy,

and their seven children.

Steven Faulkner teaches creative writing at Longwood University in southern Virginia. He is the author of Waterwalk: A Passage of Ghosts (2007) and Bitterroot: Echoes of Beauty and Loss (2016). Both books are memoirs of father-son journeys that followed the paths of missionary priests: Marquette (in Waterwalk) and De Smet (in Bitterroot).

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on poetry from the online archives

more from the online archives

23.2—March/April 2010

Job’s Progress

on Maturity for a Rising Generation by Peter J. Leithart

33.1—January/February 2020

Forbidden Lies

Speaking Truth About the Sexes Is Not Optional by Anthony Esolen

30.1—Jan/Feb 2017

Family Matters

Domestic Altars & Godly Offspring by Allan C. Carlson

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00