Entrusted to Woman

The Challenge & Mission of Christian Women Today

by Helen Hull Hitchcock

No one would deny that Christian believers—especially women—face serious challenges today. Our faith challenges us to accept our mission as believing Christians living in a culture and in an age which is openly hostile to the fundamental tenets of our faith. It also requires that we meet those challenges to our faith that we will most certainly encounter with wisdom and with responsibility.

But challenges to our faith do not come only from the world outside Christianity—the “Areopagus,” as Pope John Paul II calls it in his encyclical on the Mission of the Church, Redemptoris Missio. In fact, one of the identifying features of the current period of Christian history is that a tremendous confrontation is coming— not from atheists, or pagans, or members of other religions—but from within the Church itself. Church life today is marked by the prevalence of dissent, the divisions and disunity which dissent brings, and the rejection of perennial Christian truths and essential Christian beliefs by people who describe themselves as Christians. All Christian bodies have been affected by this phenomenon. Persecution from outside can have the effect of strengthening faith: but dissension within divides and disperses its energy, and ultimately destroys faith.

It is not only or even primarily, of course, the smooth functioning of the Church as an institution which concerns us most deeply in the midst of this dissent; but also the Church as the Body of Christ comprised, as St. Paul tells us, of individual persons—of each believer. The souls of an entire people, of an entire age, are put in jeopardy by this kind of dissent.

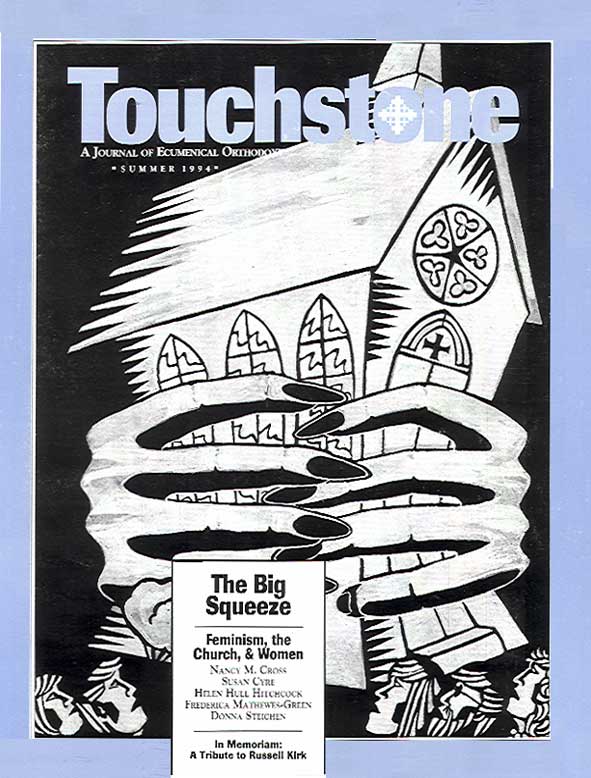

The challenges to Christian women today loom on both fronts: inside and outside the Church. The challenge from outside may be described as cultural, and it confronts the family. The challenge from inside the Church is theological, and the most significant theological controversy is that of feminism. Christian women are called to face both the cultural challenge to the family and the feminist challenge to their faith in fulfilling the challenge of their overall mission as Christians.

The Challenge of Culture & Family

The family as the “fundamental cell of society” is the key to culture. The family is the essential link connecting the past with the future. Each family provides a living connection between inherited traditions and the future which we are in the process of creating. Indeed, a principal function of the family is to transmit received culture (including religious beliefs and moral principles) to their children, the new generation of the world’s inhabitants. If the family is weakened or broken—if this link, this umbilical cord, this connection which provides its dynamism, which nourishes it and gives it life and brings the wisdom of past centuries to birth in the living present, is severed—no culture can survive.

In our time, maintaining a vital connection to the past is made difficult for many reasons (e.g., social mobility, wars, ideological revolutions, secularization, and so forth). In our society the very process of change in itself has come to be seen as both natural and inevitable (which it is) and an unqualified good (which is debatable). The point of Christianity (and of atheistic ideologies, as well) is to affect the way in which things change.

In traditional Christian thought, change —conversion—which draws man closer to God is good. Those changes which do not, or which, in fact, lead away from God, are not. The conversion process—the means by which we become Christians—is secondary to the result. If we hope to evangelize society, if we hope to effect the conversion-for-the-good, we have to give our attention to what we hope to achieve by it. And this consideration will lead to different conclusions for Christians than for non-Christians and non-believers.

There can be no culture without faith—a body of beliefs held in common. Culture, by definition, demands a coherent worldview which its members understand and to which they give not only assent but also expression. This expression may be through literature, music, architecture, fine art, philosophy, social science, education, or politics. Authentic expression of culture is bound to reflect “cultural norms”: that is, those beliefs and moral and ethical principles which are (or have been) generally accepted by the members of a social group or society. Otherwise the expression cannot be an authentic manifestation of the culture.

Culture not only proceeds from a consistent worldview, but also requires the continual reaffirmation of the set of beliefs which comprise it—the continuous building, refining, explaining, enhancing of a system of thought—the enhancement of metaphysical assumptions. A culture, although based on individual perceptions of reality and predicated on specific experiences (including geography, time, and various factors, such as war, government, and so forth), must also be able to transcend the limitations of a particular time or place, as well as the limitations of individual persons. Culture’s reaffirmation, its enhancement, must likewise have the characteristic of continuity.

Counterculture is precisely that which seeks to challenge and even destroy the prevailing cultural givens. Yet counterculture depends for its startling or even scandalizing effect, for its revolutionary power, on the existence of an intact and prevalent worldview; on the presence of a commonality of beliefs about man and the world, man and the universe, man and God, and the ultimate meaning of human existence. Even so-called anti-art—art whose point is the rejection of aesthetic givens and/or to comment critically on the prevailing culture—depends entirely for its effect on the existence of a dominant or generally accepted culture. Its message is otherwise meaningless. This type of counterculture is simply reactive and has no life of its own aside from its parisitical relationship to cultural norms. This lack of a positive vision is shared by much of postmodern culture, including feminism.

A cultural revolution takes place when such an alien set of beliefs is deliberately imposed on a given society by its leaders. This can be done directly and suddenly, as in the case of the Communist revolutions in Russia and China. It also can be done indirectly, as in the case of the more or less gradual erosion or collapse-from-within of what used to be called Christendom—civilization based on Christian moral and ethical principles.

We now find ourselves, at the end of the second millennium, at the end, also, of Christian culture. Christian moral teaching, core Christian concepts about the meaning of human life, are being rejected and attacked openly by many of the world’s most influential people, including some who claim to be Christians. But even as the remnants of Christian culture continue to decline, we also see, paradoxically, a new countercultural activity of believing Christians who hope to revive the energy of Christianity as a belief-system in an environment which has become essentially non-Christian, or even anti-Christian.

The fact that the cultural force of Christianity has been all but lost to contemporary society creates a situation not entirely unlike that which existed in Europe in the waning days of the Roman Empire. Christianity today may be nearly as countercultural as it was to the pagans of Europe during the first millennium A.D. Its essential message is as alien to jaded post-Christians of the end of the twentieth century as it was to our pre-Christian ancestors of the third.

What must we do? The challenge for all Christians is articulated well by Pope John Paul II: “It becomes necessary . . . to recover an awareness of the primacy of moral values, which are the values of the human person as such. The great task that has to be faced today for the renewal of society is that of recapturing the ultimate meaning of life and its fundamental values.”

The countercultural role of Christianity has the advantage over its post-Christian usurper of having a positive message and vision of redemption based on truth. But tragically, just when it is needed most, fidelity to that vision within the Church to which it was entrusted is often lacking. And so it is necessary to recognize the challenge of feminism from within.

Feminism & the Mission of Women

Feminism, I have become convinced, presents the most sweeping and revolutionary challenge to Christian beliefs and principles, the single greatest impediment to authentic evangelization of the world, and the most lethal subversion of the Christian faith in the history of the Church.

I am not going to attempt to present here a list of the many theological, psychological, anthropological, sociological, and spiritual challenges of feminism. Most are well aware of the depth and scope of the feminist challenge and also are very conscious that this problem—and, to a large extent, its solution, as well—centers on each individual Christian—and especially on women.

Many Christian women have at some time been personally embarrassed, ashamed, or angered at what is often promoted and demanded in the name of the “rights” of our sex. It is outrageous that feminists stereotype believing Christian women who contradict feminist fundamentalism as victims of oppression too ignorant even to understand how we are victimized and oppressed.

Instead of critiquing feminism, or listing feminism’s countless hostile challenges to society and to the Church, I will focus on two basic challenges especially to Christian women at this moment in history. Feminism makes responding to these challenges to women dramatically necessary.

In his Apostolic Exhortation issued following the Synod on the Laity, Christifidelis Laici (The Lay Members of Christ’s Faithful People) Pope John Paul II notes two “great tasks entrusted to women”:

1. “First of all, the task of bringing full dignity to the conjugal life and to motherhood. Today new possibilities are opened to women for a deeper understanding and a richer realization of human and Christian values implied in the conjugal life and the experience of motherhood. Man himself—husband and father—can be helped to overcome forms of absenteeism and of periodic presence as well as a partial fulfillment of parental responsibilities—indeed he can be involved in new and significant relations of interpersonal communion—precisely as a result of the intelligent, loving and decisive intervention of woman.”

2. “Secondly, women have the task of assuring the moral dimension of culture, the dimension—namely of a culture worthy of the person—of an individual yet social life. The Second Vatican Council seems to connect the moral dimension of culture with the participation of the lay faithful in the kingly mission of Christ: ‘Let the lay faithful by their combined efforts remedy the institutions and conditions of the world when the latter are an inducement to sin, that all such things may be conformed to the norms of justice, and may favor the practice of virtue rather than hindering it. By so doing, they will infuse culture and human works with a moral value’.”

The pope continues:

“As women increasingly participate more fully and responsibly in the activities of institutions which are associated with safeguarding the basic duty to human values in various communities, the words of the Council just quoted point to an important field in the apostolate of women: in all aspects of the life of such communities, from the socio-economic to the socio-political dimension, the personal dignity of woman and her specific vocations ought to be respected and promoted. Likewise this should be the case in living situations not only affecting the individual but also communities, not only in forms left to personal freedom and responsibility, but even in those guaranteed by just civil laws.

“. . . God entrusted the human being to woman. . . . precisely because the woman in virtue of her special experience of motherhood is seen to have a specific sensitivity towards the human person and all that constitutes the individual’s true welfare, beginning with the fundamental value of life. . . .”

Then the pope stresses the need for men and women to work together in unity both in the Church and especially in the formation of families and the education of children. This last has been a dominant theme running throughout Pope John Paul II’s works—beginning even before he was pope (in The Acting Person and Love and Responsibility). His trilogy on the Theology of the Body, his Apostolic Exhortations on the family, Familiaris Consortio, and on women, Mulieris Dignitatem, expand on these themes.

The Strategic Place of Women

Christian women and their families, then, are charged—and challenged—with the responsibility of transmitting a distinctly countercultural message to the society in which we live. It is our mission to affirm life within a culture of death—to affirm the essential moral teachings and ethical principles of Christianity. It is the Christian message which affirms what it means to be a man or a woman in this or any other society, and what it means to be a human being—in relation to other human beings and in relation to God. This message is, in essence, identical with the gospel message of love and of life which our Lord Jesus came to give us and that he suffered and died to bring us. Delivering this life-giving message is especially the vocation of women, because, as Pope John Paul II has said, God has entrusted the human being especially to women.

The ultimate challenge, the mission to which every Christian is called—a mission and a vocation conferred on us by our Lord Jesus Christ and His Church—is to bring his liberating truth into all the world. We must apply all our talents, energy, faith, hope and love to this end.

Given the collapse of Christian culture, the strategic role that women play in assuring the moral dimension of culture makes it inevitable that women must stand center stage. They remain in a vital position in the struggle to reconstitute Christian culture. The places in which small victories will accumulate into ultimate triumph over the forces of anti-Christianity (of which the feminists are but one phalanx), are not to be found in the academies or ecclesiastical offices of the churches that have been besieged and overrun by feminists and their allies. They are found in the home, the family, and the relationship of mother and child. These places have been dismissed by feminists as degrading arenas of servitude. Though sadly besieged and damaged by unchristian influences, they remain by and large under the control of Christian women. The women who embrace the challenge of family and faith stand in positions of greater power than any prelate or feminist ideologue. (Prelates are under the obligation to transmit received tradition accurately, not innovate. And ideologues ultimately must give way to the next ideological wave.) Such Christian women are in reality the strong ones, not paralyzed by feelings of victimization and weakness for which there is no real cure.

Our work must begin with the internal evangelization of the family—the source of life and the cradle of faith. We must—and can—begin to rebuild Christ’s Church from within the very heart of the “Domestic Church”—in every Christian home. To those for whom the family is too small a place, for whom the raising of children is not a socially-respected occupation, for whom the family and traditional parenting are quaint relics of an imagined misogynist past—to those and to us our Lord says plainly, “To such [children] belongs the kingdom of heaven. . . . Woe to him . . . who causes one of these little ones to stumble.” The challenge of culture and feminism to the Christian family is one that we dare not take lightly.

Contributing editor Helen Hull Hitchcock is the director of Women for Faith and Family and editor of its newsletter, Voices. She has written for Crisis, First Things, and edited The Politics of Prayer (reviewed in Touchstone, Winter 1994). She and her husband live in St. Louis, Missouri.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor