Romancing the Past

A Critical Look at Matthew Fox & the Medieval “Creation Mystics”

by Barbara Newman

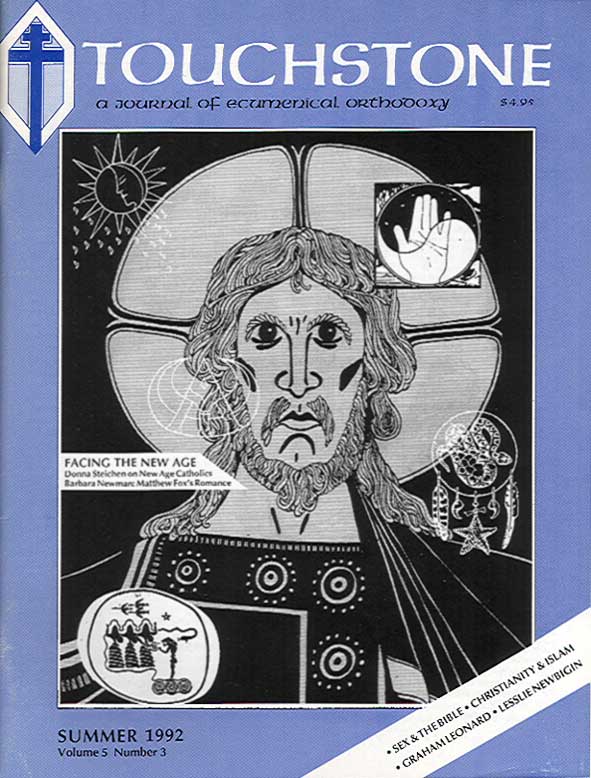

It is no exaggeration to say that Father Matthew Fox is one of the best-loved Catholic theologians in the United States. The Dominican priest had achieved celebrity through his many books, his lecture tours, and his Institute in Culture and Creation Spirituality, based in California, long before the Vatican set the seal on his prophetic career by silencing him for a year. Fox was thus honored with the same accolade once received by such theological giants as Yves Congar and Teilhard de Chardin. Unlike those thinkers, however, Fox has taken a playful and even whimsical approach to theology, as suggested by the titles of his early books: Whee! We, wee All the Way Home: A Guide to the New Sensual Spirituality (1976) and On Becoming a Musical, Mystical Bear: Spirituality American Style (1972).

The ursine mystic was immortalized in the imprint of Bear & Company, a press that Fox cofounded in 1981. For the past decade Bear & Company has promoted Fox’s brand of creation spirituality by publishing his own works, primers of the New Cosmology, and the popular “Meditations with” series, including meditations with Meister Eckhart, Julian of Norwich, Mechtild of Magdeburg, Dante, Thomas Aquinas, Native Americans, and animals. These slender volumes, featuring free adaptations of their sources arranged for daily prayer, enable the adherents of Fox’s “spirituality American style” to perceive a deep continuity between themselves and the medieval Christian past. But since much of this continuity is a fiction constructed by Bear & Company’s practice of selective editing and dubious translation, the press’s successful promotion of these texts creates a problem for anyone concerned with historical as well as spiritual truth-in-packaging.

The questions raised by Fox’s enterprise are large and intractable ones: Does the theologian have a responsibility to the past as well as the present? What is the place of historical theology in contemporary religious thought? Can we create a usable past for ourselves and, at the same time, remain or become historically honest? Is there a timeless core of Christian truth that can and should be stripped of its antiquated garb to be made forever new? What, in fact, is Holy Tradition and how should we use it? I have chosen Matthew Fox as a case study because his work poses the problem in acute form, but any theologian who grapples seriously with tradition must face the same issues. I have chosen his work on St. Hildegard because she has been the focus of my own scholarly efforts, as well as the centerpiece of Fox’s attempt to rewrite Christian history.

Taking pride of place in his list of “creation-centered mystics,” Hildegard is featured not only in a a “Meditations” volume1 but also in Fox’s Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen (1985) and in a series of translations published by Bear & Company. Little-known in the Anglophone world before 1980, Hildegard was a twelfth-century German prophet and visionary. A Benedictine abbess and founder, she was also a monastic reformer, preacher, composer and liturgist, medical writer, and prolific theologian who was and still is venerated as a saint in her homeland, although she narrowly missed canonization.2 In the mid-1970s, when I was a graduate student hunting for a suitably arcane dissertation topic in medieval studies, I came upon St. Hildegard almost by chance and fell under her spell at once. At that time few scholars in America had ever heard of Hildegard and fewer still had read her. But a decade later, when my book finally appeared,3 it had a ready-made public at hand. I discovered that my author, recently so obscure, now had fans in every quarter thanks to the efforts of Bear & Company. Whenever Hildegard’s name came up for discussion, I was inevitably asked what I thought of Matthew Fox. From a selfish point of view, of course, I had reason to be grateful to him. Yet the more I read of his work on medieval mysticism, the more ambivalent I became.

On the one hand, there is much to admire in Fox’s theological project. On the other, much of what he says about Hildegard, and every other historical figure he cites, turns out to be dead wrong—factually careless, anachronistic, and tendentious. Numerous quotations are drawn not from her original Latin texts but from Bear & Company’s Meditations—edifying snippets taken out of context, translated secondhand from the German, bowdlerized to remove offending language, and paraphrased in a relentlessly banal and simplistic style. Not surprisingly, Hildegard subjected to this treatment sounds much like Meister Eckhart, just as Thomas Aquinas sounds like Matthew Fox and Dante like a Hallmark card. Having remastered these ancient voices in a contemporary mode, Fox then proceeds to celebrate them as exemplars of a “creation-centered tradition” culminating in his own theological synthesis, which is most fully and eloquently set forth in his recent book, The Coming of the Cosmic Christ (1988).

In order to appreciate the value Fox assigns to medieval mystics, it is necessary to understand his larger theological program. This program is radical and ambitious, and it is advanced with a passionate urgency inspired by the planetary crisis we now face. What Fox seeks is nothing more nor less than a “paradigm shift” in theology-from a fall/redemption to a creation-centered spirituality, from original sin to original blessing, from world-denying asceticism to life-affirming mysticism, from patriarchy to feminism, from repression to celebration of the body, from an anthropocentric focus on the self to an ecological focus on the cosmos. Fox’s Christology is predictably broad. Although he retains an interest in the historical Jesus (whom he interprets as a creation-centered mystic, crucified for his frontal assault on patriarchy), his real quest is directed toward the cosmic Christ, whom he sees incarnate in the universe as a whole. In The Coming of the Cosmic Christ, Fox goes so far as to identify Jesus crucified with Mother Earth, “dying at the hands of a patriarchal civilization gone mad with its attraction to matricide.”4

To save the planet and the human race, he proposes what is in effect a new religion that will unite the powerful energies of art, science, and mysticism—Fox’s “holy trinity”—in the service of wisdom and justice, compassion and celebration. This religion is not unlike that proposed by many spiritual teachers in the New Age movement; one can find similar prophetic and mystical teachings under the aegis of Hinduism, Sufism, Wicca, and a variety of other rubrics. Indeed, Fox practices what he calls “deep ecumenism,” noting that in parts of the world today, the religious lines of demarcation no longer separate Catholics from Protestants or even Christians from non-Christians so much as they divide progressives from conservatives within all traditions. Consequently Fox feels closer in spirit to a native American shaman, a feminist witch, or a Sufi master than he does to a repressive cardinal or an Opus Dei bishop.5

Fox’s theology in fact bears little resemblance to any historic form of Christianity. Although he finds much to admire in the Bible, he has drawn far more from other sources, and Jesus is no more central to Fox’s religion than he is to Islam. Yet Fox is a Dominican priest and his audience consists largely of disaffected Catholics, including a great many clergy and religious. For this reason, he must legitimate creation-centered spirituality for Christians by grounding it, so far as possible, within his own reading of the Christian tradition. Like most theologians, Fox has his own version of Church history with his personal heroes and villains. Two of the prime villains are St. Augustine and Isaac Newton, who inaugurated earlier paradigm shifts—Augustine turning from the cosmic Christ of the Greek Fathers to the “personal Savior” of his own guilt-obsessed psyche, and Newton from a mystical cosmology to a soulless world-machine. Fox’s heroes are the so-called creation mystics of the Middle Ages—Hildegard, Eckhart, and the rest. In order to cast them in this role, however, he is compelled to suppress or distort much of their actual teaching. His representation of Hildegard is a prime case in point.

Bear & Company’s translation of this Scivias, the first volume of Hildegard’s theological trilogy, is abridged to about half its original length. The omitted sections are those which the editor deemed “irrelevant or difficult to comprehend today.”6 Among these are lengthy passages promoting orthodox sexual ethics, commending virginity, expounding the theology of baptism and Eucharist, condemning heresy, upholding priestly ordination and celibacy, defending the feudal privilege of nobles, and exhorting the obedience of subjects. In other words, Hildegard is welcome to Fox’s mystical pantheon so long as she refrains from being a twelfth-century Catholic. Her holistic cosmology is acceptable, but not her defense of social and ecclesiastical hierarchies. Fox is delighted to stress her “womanly wisdom” but ignores the fact that she was a consecrated virgin, blithely ascribing to her his own ideas about “the recovery of Eros.” Since he also wants to make her a feminist, he rigorously edits her trinitarian thought to fit the standards of an inclusive-language lectionary. The divine Mother, who figures prominently in Hildegard’s visions, is allowed to remain; but the Father and his Son are ushered firmly out the door. Fox does not overtly criticize these unpalatable aspects of Hildegard’s thought; he simply ignores them.

In another translated volume, Fox praises Hildegard for her supposed rejection of all dualism, which is perhaps the closest thing to an original sin in his worldview. According to Hildegard’s teaching, Fox writes in his preface, “depression comes from dualism.”7 In truth body and soul, Creator and creation are one. Yet in the text that follows—despite careful editing to remove unacceptable language—Hildegard makes statements whose dualistic bent is hard to deny. “Whoever shows devout faith . . . by scorning earthly things, and by revering heavenly things, will be counted as righteous.”8 Again, “we cannot at the same time serve God and the Devil because whatever God loves, the Devil hates . . . The flesh finds delight in what is sinful, and the soul thirsts after justice.”9 One might or might not agree with such teaching, but it is in no way exceptional either for Hildegard or for the mainstream Catholic doctrine of her time (or any time before 1960). My point is not that Hildegard is right and Matthew Fox wrong. What disturbs me is that he makes her the mouthpiece for ideas she never held, and in fact explicitly rejected. Fox may believe he is announcing what Hildegard would have said if she were alive today, but that is a judgment no one has the right to present as historical fact.

As an aid to understand Hildegard’s Book of Divine Works, Fox offers what he calls a “creation-centered grid for reading the creation mystics.”10 This study guide is in fact the table of contents from Original Blessing, his own work of systematic theology (1983). Many of Fox’s key theological themes do figure in Hildegard’s work, but others are quite foreign to it and can only mislead. For instance, the grid would ascribe to her a realized eschatology, whereas she was known throughout the Middle Ages for her apocalyptic prophecies representing the eschaton as a series of world-historical events in the future.11 Fox’s schema credits her with a “recovery of the art of savoring pleasure” and a firm “no” to asceticism—although much of the Scivias is devoted to classic Benedictine virtues like humility, obedience, discipline, moderation, chastity, compunction, and contempt for the world. He looks to her as a source for his “spirituality of the anawim,” defined as “feminists, Third World, lay, and other oppressed peoples,” although Hildegard held characteristically medieval views of gender, advocated subjection of the laity, and had never heard of the Third World. She had heard of pagans and unbelievers, whom she regarded as people deceived by the Devil’s lies; their fate was to be cut from the tree of life, like decaying branches, by the sword of the Trinity.12 I do not personally relish this doctrine any more than Fox does, but Hildegard did believe it.

Bear & Company has also promoted some distinctly odd ideas about Hildegard’s life and times. Although she lived in the Rhineland in the twelfth century, spoke German as her mother tongue, and was steeped in the Latin clerical culture of her time, Fox insists on describing her spirituality as Celtic. With a stunning lack of evidence, he maintains further that “the Celts who settled so deeply into the Rhineland area were closely linked in their spirituality to the Hindu.”13 American Indians, too, made their contributions. Seeing through the eyes of one of his Native American friends, Fox manages to find the “corn man and woman” of Hopi sacred art concealed in a portrait of Hildegard receiving divine inspiration. “Perhaps,” Fox writes, “this is due to the fact that both Native American and the woman’s or Chthonic tradition of Germany go back to pre-patriarchal times and thus share archetypes common to matrilinear cultures. But there is another explanation as well,” involving our intrepid friends, the Celts. These voyages are supposed to have visited the New World centuries before Columbus, returned with a rich store of Native tales and images, and then “settled all along the Rhine and deeply influenced the mysticism of that area.”14

Given Fox’s idiosyncratic version of history, it is not surprising that “a woman in an Indian sari” who attended one of his lectures found Hildegard’s “mandalas” to be “deeply Hindu.” And “an old Native American man with only one tooth” told him that she was “one of us also.”15 Unfortunately, this moving testimony was inspired by the miniatures that appear in a famous manuscript of Hildegard’s Scivias. There is no evidence that the abbess herself painted these brilliant illuminations, and at one point in his writings, Fox admits that she did not.16 But he wants them to be hers because they are beautiful, and because art as meditation is an important part of his program. So he decides to speak of Hildegard elsewhere in his books and lectures as a painter, mere historical evidence being subordinate to a higher truth. Fox believes that Hildegard is responsible for the paintings in spirit, and in any case, they embody for him revelations of the sacred so deep and universal that petty questions of authenticity do not matter.

Fox’s cavalier attitude to history has a long pedigree. His “deep ecumenism” recalls the popular liberal idea that “all religions are one,” or less crudely, that in each tradition there is an esoteric or mystical core where sectarian differences vanish, so that those who follow any spiritual path to the end will converge. Thomas Merton’s dialogue with Buddhist monks, toward the end of his life, helped make this idea acceptable to Catholics who already admired his contemplative spirit and his work for peace and justice. Fox is also indebted to Jung’s theory of archetypes and to scholars like Mircea Eliade and Joseph Campbell, whose work in the history of religions stressed universal patterns rather than historical and cultural differences. If the human mind is everywhere the same—at least at the level of the collective unconscious—these affinities between Hindu, Celtic, Native American, and medieval Catholic traditions are exactly what one should expect, once the merely superficial and time-bound elements have been swept away. Moreover, the idea of a single, universal revelation to all humans, through creation itself, seems compatible with the biblical idea of one loving God who “wills all people to come to a knowledge of the truth.” This belief in a universal, “ecumenical” mysticism may be strengthened, at least in some people’s eyes, by fanciful claims about Celtic influence in the Rhineland and Native American elements in the medieval Church.

For one who believes as Fox does, therefore, the historian’s concerns with accuracy, reliable sources, fidelity to the evidence, and properly contextualized reading would seem trivial at best, or at worst, an affront to the Spirit. I doubt very much that Fox would be troubled by my account of his errors. He would probably ascribe such a critique to excessive and unhealthy reliance on the “left brain,” or discursive analytical thought, and an atrophy of the “right brain” which “accomplishes the synthetic, sensual, and mystical tasks.”17 Mystics like Hildegard must be read with the right brain, he insists; a fitting response to them can be evoked in meditation, song and dance, holistic and creative interaction, rather than dry academic study. The real reason for reading medieval mystics and prophets in our day, Fox remarks, is “not to do them honor but to awaken the mystic/prophet in us.”18 In his view, all people are potentially mystics. One of the great tragedies of our time is that this potential is unused; it needs to be reawakened through contact with the great, creation-centered mystics of the past. On this point Fox aptly quotes Hildegard’s own assertion that God inspired her to write “for the usefulness of believers,” since he destroys everything useless.

A final reason for Fox’s indifference to historical truth lies in his need to reclaim tradition—his own tradition—on behalf of his personal theological vision. Here he is quite explicit: “Ecumenism need not mean dashing off to foreign shores to find spiritual nourishment—at least it need no longer mean that. With giants like Hildegard and Eckhart, Francis and Aquinas, Mechtild and Dante, Julian and Nicholas of Cusa, the West can cease its mystical embarrassment vis-à-vis the East.”19 This “embarrassment” was no doubt acutely painful to Catholics in the late ’60s and ’70s, when Fox was beginning his theological work and Christians in droves were abandoning their ancestral faith to sit at the feet of Eastern meditation masters. Through Bear & Company’s “meditations” series, Fox was able to provide a homegrown alternative tradition that offered much the same teaching in native dress. In deference to his own Dominican order, he even includes the inexorably “left-brained” Aquinas among his creation mystics.

These medieval saints supply an alternative, not only to New Age gurus from the East, but also to the outworn tradition of “fall/redemption spirituality” which Fox attributes to the nefarious influence of Augustine. Since it is vital to him to liberate the Church from the stranglehold of this theology, he attacks it both by direct assault and by attempting to break its monopoly as the dominant historical interpretation of Christian faith. As long as his followers do not attempt to read his “creation mystics” in unexpurgated texts, he supplies them with an attractive and persuasive revisionist history of doctrine, which both legitimates his own theology and makes the Middle Ages seem more appealing than they ever did in seminary.

In my critique of Fox I have relied on the canons of secular history, which ostensibly seeks to interpret men and women of the past in the context of their own culture and motivations, without regard for contemporary ideological needs. Of course we all know that historians are not without bias; the goal of a purely objective history is an illusion, or at best an unattainable ideal. But even the ideal of objectivity is, historically speaking, a fairly recent phenomenon, and one that has made only limited inroads in the field of Church history. Since its beginnings in the era of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, church history has been largely an apologetic enterprise in which rival parties have sought to enlist the past on their side. Biblical and patristic studies have been most vulnerable to this tendency, but a few hardy Protestants have attempted to reclaim even medieval Christianity, or at least medieval heresy, for the cause of Reform.

In the generation of Henri de Lubac and Marie-Dominique Chenu, Matthew Fox’s teacher, the lines of force within Catholicism divided proponents of neo-Scholasticism from more liberal thinkers, some of whom found a refuge from ossified Thomism in twelfth-century thought. One might call these famous medievalists “pre-Thomist” in the same aggressive sense that fin de siècle painters called themselves pre-Raphaelite. Catholic writers have long used contrasting appropriations of the medieval period to support conflicting theological views. Of course, de Lubac and Chenu were infinitely better historians than Matthew Fox. But the creative scholarship of their generation provides a precedent for Fox’s project, at least in his view, for he has claimed Chenu’s legacy as a way of validating his own work. Fox’s medievalism, however, is so lacking in scholarly credibility that it is hard to see him as a faithful heir of Chenu. If we set the radicalism of his doctrine aside and look only at his use of history, he seems to be treating the past less as his teachers did than as the most traditional Orthodox and pre-modern Christians have done.

In the Orthodox Church, there is virtually no discipline of Church history in the sense of what Cardinal Newman called “the development of Christian doctrine.” Instead there is historical theology—attentive readings of individual theologians in the light of Holy Tradition. The reason for this gap is that Orthodoxy in general lacks the historicism that has characterized the Protestant churches since the nineteenth century and the Catholic Church—or parts of it—since the mid-twentieth. The prevailing Orthodox view still holds that Tradition speaks with a single voice, if not through a single mouth. Although individual teachers have their own distinctive emphases and may, on occasion, fall into error, the Church as a whole has always taught the same unchanging, ecumenical truth. Major divergence from this truth constitutes heresy; minor divergence within it barely matters. Thus, aside from a small coterie of scholars, the claim that Gregory of Nyssa held one view, and John Chrysostom quite another, would meet with little understanding.

Matthew Fox’s notion of an entire, submerged alternative tradition within the dominant tradition would be incomprehensible from an Orthodox perspective. Yet his method—harmonizing and homogenizing diverse voices in order to present the tradition as a whole—would come as second nature, for that is what Orthodox thinkers have always done. But since Fox in reality stands far from the traditional Church, he evades and suppresses what I have exposed as a conflict between historical truth and pastoral usefulness, sacrificing the former to serve the latter. In an Orthodox milieu, both historicism and contemporary needs would be sacrificed to the integrity of Tradition, which is perceived as the unique divine Truth and therefore the most “useful” pastoral message for all ages. A few tentative voices have only begun to suggest that more explicit concern with contemporary problems might represent God’s will for the Church. It remains to be seen whether they will find a hearing.

Meanwhile, the dilemma posed by Fox’s treatment of history admits no easy solution. I have argued that, whatever the appeal of his theology, there is something fundamentally dishonest in the way he grafts it onto an imagined medieval past. Scholars who have made exacting studies of Eckhart, Aquinas, and others in his pantheon would agree. On the other hand, we cannot ignore the dangers inherent in a merely academic historicism, which may begin with irrelevance and end by fulfilling Fox’s dire prediction that, if we fail to awaken “the mystic/prophet within us,” our right brains will become “dried-up prunes” and our planet will succumb to matricide at last.20 The only alternative I have to offer is the common-sense, unromantic idea that we need to respect the past as history and tradition, for to engage in willful distortion of history is to break faith with the holy dead, and to neglect tradition is to break faith with the whole Church, sacrificing the common life of Christians for the sake of our individual taste.

At the same time, we cannot and dare not ignore the signs of the times, which Christ himself challenged us to discern. What is required of us, I believe, is a process of bold yet meticulous sorting. We do need, time and again, to reclaim the past, but we also need the courage to reject as well as affirm when we sift through its manifold gifts. Not everything we find in Christian Tradition will be to our liking. Our task at times may be to suppress our likings insofar as the gospel demands; at others, it may be to call Tradition itself to account as the Spirit moves. But in no case will the work of either creation or redemption be advanced by the mystification of history, however well meant it may appear.

Notes:

1. Gabrielle Uhlein, Meditations with Hildegard of Bingen (Santa Fe: Bear & Co., 1982).

2. Reliable accounts of Hildegard include Sabina Flanagan, Hildegard of Bingen, 1098-1179: A Visionary Life (London: Routledge, 1989) and Peter Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1984), chapter 6. For an introduction to her writings see Fiona Bowie and Oliver Davies, eds., Hildegard of Bingen: Mystical Writings (New York: Crossroad, 1990).

3. Barbara Newman, Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine (Berkeley: Univ. of California Press, 1987).

4. Matthew Fox, The Coming of the Cosmic Christ: The Healing of Mother Earth and the Birth of a Global Renaissance (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1988): 148.

5. Ibid. 235-39.

6. Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias, trans. Bruce Hozeski (Santa Fe: Bear & Co., 1986): vii.

7. Hildegard of Bingen, Book of Divine Works, with Letters and Songs, ed. Matthew Fox (Santa Fe: Bear & Co., 1987): xv-xvi.

8. Ibid. I.16, p. 20.

9. Ibid, II.47, p. 54.

10. Ibid, xix-xxi.

11. Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, Reformist Apocalypticism and “Piers Plowman” (Cambridge, 1990), chapter 2.

12. Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias III.7, trans. Columba Hart and Jane Bishop (New York: Paulist, 1990): 411-14.

13. Matthew Fox, Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen (Santa Fe: Bear & Co., 1985): 16.

14. Ibid. 29.

15. Cosmic Christ, 230-31.

16. Illuminations, 10.

17. Cosmic Christ, 18.

18. Book of Divine Works, xviii.

19. Illuminations, 16.

20. Cosmic Christ, 18.

Barbara Newman, Ph.D., is Professor of English and Religion at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Her books include Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), and Symphonia: A critical edition of the “Symphonia armonia celestium revelationum” of St. Hildegard of Bingen (with introduction, translation and commentary, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988. Dr. Newman is a member of the Orthodox Church in America.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor