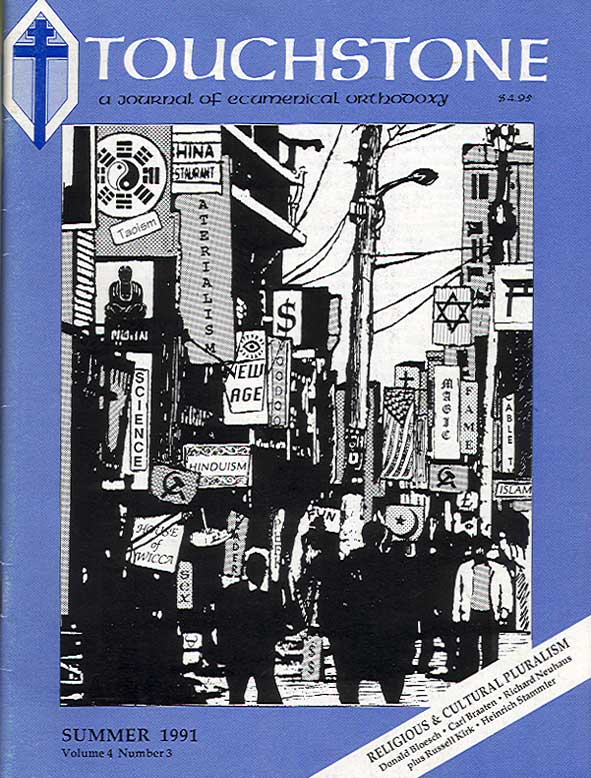

The Finality of Christ & Religious Pluralism

by Donald G. Bloesch

With the rise of neo-Protestant theology in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and neo-Catholic theology in the twentieth century, a new theological model has emerged into prominence that seriously calls into question the exclusivistic claims of traditional Christian faith. The new paradigm has been facilitated by the Church’s encounter in the early nineteenth century with Romanticism with its emphasis on individuality, pluralism, and relativism. It was Schleiermacher (d. 1834) who exulted in the plurality of the modern world: “Let none offer the seekers a system making exclusive claim to truth, but let each man offer his characteristic, individual presentation.”1

The History of Religions school associated with such names as Ernst Troeltsch (d. 1923) and Johannes Weiss (d. 1914) also paved the way for modern relativism and pluralism. For Troeltsch there is no final revelation: the Divine Life within history always manifests itself in new and peculiar individualizations. Truth has many forms; ultimate reality is necessarily apprehended in a variety of ways, all of which have some claim to validity.

The emerging philosophy of pragmatism from the later nineteenth century on gave additional impetus to the slide toward relativism and pluralism. William James (d. 1910), who has had a unmistakable influence on both process theology and New Age theology, advanced the notion of a pluralistic universe, which allows for the coexistence of conflicting religious claims.

More recently, with the rise of the “theology of religions,” the uniqueness of Christian revelation has been further called into question. Paul Knitter of Xavier University in Cincinnati says that we need to “recognize the possibility that other ‘saviours’ have carried out . . . for other people” the redemptive work which as Christians we know in Jesus Christ.2 For Knitter the common ground of religion exists in the struggle to liberate the oppressed peoples of the world. Eugene C. Bianchi upholds a “Christian polytheism,” which allows for other savior figures besides Christ. Hans Küng contends that a person “is to be saved within the religion that is made available to him in his historical situation. Hence it is right and his duty to seek God within that religion in which the hidden God has already found him.”3 Calling for a “global religious vision” John Hick avers that it is no longer necessary “to insist . . . upon the uniqueness and superiority of Christianity; and it may be possible to recognize the separate validity of the other great world religions. . . .”4

The ascendancy of the new theological orientation can be described in various ways. Samuel Moffett, veteran Presbyterian missionary to Korea, views the nineteenth century as the age of missions, the early and middle part of the twentieth century as the age of ecumenism, and the present period as the age of religious pluralism. New Agers describe this last stage as the “Age of Aquarius,” marked by the celebration of the intuitive over the cerebral. Whatever images are used, it cannot be doubted that an exclusive monotheism is being challenged and in many cases supplanted by a religious pluralism that borders on syncretism.

Traditionally for Christians the soundness of any particular theological position was finally measured by how it stood on Jesus Christ. But now we have entered a period when our religious unity is to be found simply in the experience of a divine presence that takes multitudinous forms. This presence is variously called the Higher Self, the World Spirit, the Life Force, and the Creative Surge. A holistic vision has taken the place of the dualism of Descartes’ era; humanity and nature are now treated as dimensions of a single cosmic unity. Thus the utter transcendence of God is either seriously compromised or flatly repudiated.

Despite traditional voices within the Christian community, it cannot be denied that a new cultural paradigm, which is antagonistic toward any claim to exclusive truth, now holds sway over most of the nations of the Western world. This is also true for the nations of Eastern Europe, including the Soviet Union, which are resolutely abandoning the inflexible dogmatism of Marxist socialism for freedom, autonomy, and individuality. If one considers the reigning mentality in academic religious circles today, one must conclude that there has been a paradigmatic shift of immense proportions from a theology of transcendence to a theology of radical immanence in which God, present in all creation, is indistinguishable from creation. Predictably, traditional dogma has been eroded in favor of relativism and mysticism. Heresy as a valid theological concern is now out of fashion, although heresy in fact is stronger than ever. The Christ of Chalcedonian orthodoxy is in palpable eclipse in most circles, except those of traditional Roman Catholicism, confessional Evangelicalism, and Eastern Orthodoxy. And orthodoxy is no longer even considered a worthy theological goal.

The new trends in biblical criticism further foster this relativistic mentality. Structuralism finds the meaning of the text in the literary form which the text embodies; questions of historical reliability and ontological truth are conveniently left to the historians and philosophers respectively. Reader-responsive criticism (McKnight) now finds the meaning of the text in the subjective response of the reader. For the deconstructionist, the literary structures are changing because language is fluid; there is consequently no solid text the interpreter can work with. The notion that the Bible gives infallible information concerning the will and purpose of God is regarded by most of the new biblical critics as a relic of an outmoded dogmatism.

The common thread in most of the new theologies is denial of Jesus Christ as the very God himself, as a divine person in two natures. Instead we are directed to a Christ who is the decisive realization of human possibilities or the embodiment of some eternal value or ideal. The new heresies verge toward either an ebionitic interpretation (beginning with his humanity) or a docetic interpretation (beginning with some abstract idea of Christ).

A Reaffirmation of Biblical Christianity

In countering these new theologies we need to stand in perceptible continuity with the ancient ecumenical councils. Christ is not the maturation of the human spirit or the mirror of a transcendent ideal, or the flower of humanity, but the incarnation of the preexistent Word of God, the second person of the Trinity: in Christ we encounter the very God himself. Against the new theologies Christians faithful to the biblical revelation must again affirm what Emil Brunner aptly called the scandal of particularity—the inexplicable fact that God revealed himself among one particular people in history, the Jews, that God became man at one point in history, and that his revelation in this people and in this person is definitive and final. God revealed himself once for all in this particular event or events. In the catholic evangelical theology I uphold, the superiority of Christianity lies in its willingness to be continually purified and reformed in the light of the one great revelation of God in Jesus Christ, which cannot be duplicated but only heralded and obeyed.

As biblical Christians we must also affirm the scandal of universality, viz., that this one revelation is intended for all, that Christ’s salvation goes out to all, including the outsider and the sinner. The kingdom of God seeks to embrace not only the people of Israel, not only people of faith, but the whole world, including the enemies of faith, though the pathway into the kingdom is only through faith and repentance. Christ died not for the righteous but for sinners; he justifies not the godly but the ungodly.

As evangelical Christians we need to reclaim the biblical message that Jesus Christ is God incarnate and that he came into this world to deliver a lost humanity from bondage to sin, death, and the devil. Jesus is indeed our example as well as our Savior, but his mission was first to save, then to lead.

Biblical Christianity is focused on hearing, not seeing. The kingdom of God is not a visible reality but an invisible one that makes its way in the world only through the proclamation of the gospel. The new theologies speak of imaging God in order to make him real for human experience.5 Evangelical theology reaffirms the commandment against graven images and extends this to a prohibition against mental images of God as well. The true God is incomprehensible and invisible; he cannot be made known until he makes himself known. And he has made himself know fully and decisively only in one person, Jesus Christ. We make contact with Christ only through hearing the gospel, which we encounter in the Bible and the proclamation of the Church. Luther said, “In order to see God we must learn to put our eyes into our ears.’’ This, it seems, is the biblical way, and all other ways lead to obfuscation and deception.

Revelation includes the experiential and the conceptual, but it goes beyond these: it basically concerns the self-disclosure of the very reality of the living God in the person of his Son. Revelation happened in the divine-human encounter that we see in the life history of Jesus, but it happens ever again as the Spirit of God awakens us to the significance of that encounter for lives here and now. Revelation in the Bible indicates an authentic unveiling of the mystery of the divine presence and reality.

In contrast, general revelation (which might be more appropriately termed a general awareness of God), gives us no real, substantial knowledge of God, but only an anticipatory intimation of his love and judgment. Theologians who build on general revelation are also ineluctably led to construct a natural theology, which in my view is always a dead end road. God’s light is invariably misinterpreted and distorted because of human sin, which clouds our cognitive capabilities. I fully agree with Gregory of Nyssa that “we cannot see God in nature, but we can try to see nature in God.”

Karl Barth has been helpful in his conception of “little lights” and “other true words” that the Christian is able to discern in nature and in other religions by virtue of the one great light of Christ that makes these lesser lights and words intelligible and credible. In his later writings Barth alluded to a third circle of witnesses outside the Bible and the Church that magnify the name of Christ and testify to his goodness. But only people of faith by virtue of the opening of their eyes to the revelation of the glory of God in Jesus Christ can validly assess these other words and lights, which always constitute something alien and discordant in the systems and credos of the world of unbelief.

This brings us to the enigmatic relationship between Christianity and the great world religions. I think we would do well to emphasize today that while Christianity is indeed one of the world religions, it must be sharply differentiated from all other religions in terms of its origin and goal. Biblical Christianity affirms that the Christian religion is founded on a unique revelation of God to humankind in the person of Jesus Christ and that this religion is a sign and witness to God’s self-revelation. Christianity as a revelation must be distinguished from Christianity as an empirical religion, but the former can be perceived only through the eyes of faith. Christianity as an empirical phenomenon can be compared with other religions, but it must be judged theologically on the grounds of its unique foundation, which lies outside the confines of a phenomenological analysis of religion. Thus the world religions should be treated not as ways to salvation but perhaps as pointers to salvation. Then they would not be categorically or uniformly repudiated as agencies of damnation, but regarded as signs of contradiction, for their conceptions of God unfailingly conflict with God’s disclosure of himself in Jesus Christ.

I propose with Barth, Kraemer, and others a Christocentric view of religions which acclaims Jesus Christ as both their fulfillment and negation. This is neither religious imperialism nor churchly triumphalism but a humble acknowledgment that salvific truth is not the property, as such, of any particular religion and that the redemption of humanity’s religious impulse entails looking beyond all outward forms and credos to the living God himself, who directs peoples of all religions to his once for all intervention in the person of Jesus Christ.

This revelation overturns the idols of the religious imagination of all peoples, including Christians; the pathway to the regeneration of the religions lies in the personal transformation of religious and not so religious people by the power of the gospel of the cross.

Finally, it is incumbent on biblical Christians to affirm once again that the mission of the Church is the evangelizing of the world and the equipping of the saints for the arduous life of discipleship under the cross. To reconceive the church’s mission as the self-development of oppressed peoples or the civilizing of backward peoples is to move away from New Testament Christianity to a vague humanitarianism.

The mission of the Church is to herald the coming kingdom of God. We as Christians can prepare the way for the kingdom, we can manifest and demonstrate its power, but God in his own time and way brings in the kingdom. The task of the Church is a modest one: to wait, pray and hope for the coming of the kingdom, to witness to and acclaim God’s redeeming and sanctifying work. The Church can create parables and signs of the kingdom, but it cannot extend or fortify the kingdom through its own power and strategy. We should not say with the philosopher Hegel: “The Kingdom of God is coming, and our hands are busy at its delivery.”6 God builds his kingdom through his own power and initiative, but he enlists us as co-workers in making the promise of the kingdom known to the world.

An Emerging Confessional Situation

Theologians of various persuasions are beginning to speak of a new confessional situation as the Church finds itself engulfed in a crisis concerning the integrity of its message and the validity of its language. The many attempts today to resymbolize God and to reconceive Christ are signs that people of faith may be called again to battle for the truth, to engage in a new Kirchenkampf (church struggle).

The problem of theological authority has become especially acute, since it would seem that cultural experience is supplanting the biblical witness as the ruling criterion for faith and practice. A neo-Gnosticism is emerging that locates truth in the alteration of consciousness rather than in an event in sacred history. The philosopher Schopenhauer (d. 1860), the favorite of many New Agers, has declared that we are justified neither by faith nor by works but by knowledge. Tillich’s contention that self-discovery is God-discovery betrays a sort of Gnostic mentality we see increasingly gaining acceptance.

In feminist circles there is a call for a new canon and a Third Testament that would drastically alter the foundations of the faith. Rosemary Ruether pleads for augmenting the canon with writings that manifest a sensitivity to the concerns of women and other oppressed peoples. She recommends including tracts drawn from goddess religions, Gnosticism, and marginal Christian traditions often deemed heretical.7

The new mood in the culture was strikingly anticipated in the nineteenth century by Ralph Waldo Emerson, one of the mentors of the new spirituality: “Man is weak to the extent that he looks outside himself for help. It is only as he throws himself unhesitatingly upon the God within himself that he learns his own power and works miracles.”8 The motto of the New Age is struggle, growth, and freedom as opposed to the biblical motto—faith, repentance, and service.

The loss of transcendence is especially disconcerting when we consider the theological options today. There seems to be a confluence of various theological movements (liberationist, feminist, neo-mystical, process) toward a religion of radical immanence in which human experience and imagination preempt biblical revelation as the measuring rod for truth.

That real heresy is now a problem in the Church is attested by the frequent attempts to downgrade the Old Testament. Johann Semler (d. 1791), one of the first German theologians to apply the historical-critical method to the study of Scripture, described the Old Testament as “a collection of crude Jewish prejudices diametrically opposed to Christianity.”9 Complaining that the Old Testament promotes a legalistic type of thought, Schleiermacher recommended that it be ranked as a mere appendage to the New Testament.10 Radical feminists see the Old Testament as incurably patriarchal and the Sky Father, the supposed god of the Old Testament, as an obstacle to women’s liberation.11 Existentialist and process theologians view large parts of the Bible as mythological and have assigned themselves the task of translating what they consider basically poetry into a modern ontology. There is some sentiment in liberationist circles to deemphasize the Jewish matrix of Scripture out of a commitment to the rights of Palestinians.

What is ominous is that the new theologies, which are for the most part aligned with ideological movements, are seeking to revamp the worship practices of the Church. Prayer books and hymnals are being altered, Father-language for God is being drastically curtailed, and new symbols for God are being offered: the infinite depth and ground of all being, the creative process, the Womb of Being, the Primal Matrix, the pool of unlimited power, the new Being, the power of being, the Eternal Now, and so forth. Try praying to one of these!

In November 1989 the Anglican Church in New Zealand introduced a prayer book that not only eliminated allegedly sexist language but also dropped most references to Zion and Israel. It was explained that a prayer manual was needed to offer texts more relevant to the Maoris and South Pacific Islanders. Wendy Ross, president of the New Zealand Jewish Council uttered this protest: “The only precedent for this was the German church during the Nazi era that wanted to de-judaize the Scriptures. . . . We regard the removal of the words Zion and Israel in most cases as profoundly anti-Jewish.”12

This calls to mind close parallels between the religious situation today and the situation of the church in Germany in the later 1920s and 1930s. The so-called German Christians were especially intent on combatting the idea that revelation was limited to biblical times: it continues, they said, throughout human history—in every culture and race. The religious intuitions of the German people were deemed equal (if not superior) in authority to the insights of the Bible. Scripture was reinterpreted through the lens of the Volkgeist (the spirit of the Germanic people). A concerted attempt was made to purge the Bible of Judaic expressions like Zion and hallelujah. Interestingly, in some radical circles God was conceived of androgynously and referred to as Father-Mother. And it should be noted that the German Christians enlisted in their support some of the leading theologians and biblical scholars of that day.

As in prewar Germany, there is currently in the nations of the West a resurgence of interest in the occult, a growing openness to Eastern religions, and the rise of a naturistic mysticism. Pluralism is celebrated as something good in its own right; the destructive or demonic side of religion is conveniently overlooked. An inclusivistic mentality regards with disdain any appeal to a particular revelation or any absolutist claim to religious truth.

Nevertheless, the god of pluralism and inclusivism can be a jealous god; whatever does not fit into a pluralistic or globalistic agenda is condemned as backward and provincial. Theological seminaries in the mainline churches today are remarkably open to including Buddhists and Hindus on their staff but are adamantly opposed to inviting scholars identified with either traditional Catholicism or the evangelical side of Protestantism.

The battle today is between the historical Christian faith with its confession of the reality of a supernatural God and the uniqueness of Jesus Christ, and the new spirituality, which embraces most of the recent theological and religious movements. It is the difference between a biblical monotheism and a naturalistic panentheism, between a catholic evangelicalism on the one hand and neo-mysticism and neo-Gnosticism on the other. One side champions an inclusivistic or global vision; the other defends both the particularity of divine revelation and the universality of its claims and mission.

In its witness the Church should not press for a return to a monolithic society in which church and state work together to ensure a Christian civilization, for this can only draw the Church away from its redemptive message and blur the lines between Church and world. Neither should the Church withdraw from society and cultivate little bastions of righteousness that strive to preserve the ethical and religious values handed down from the past. Instead, the Church should witness to the truth of the gospel in the very midst of society in the hope and expectation that this truth will work as the leaven that turns society toward a higher degree of justice and freedom. The Church should serve the kingdom of righteousness by reminding the world that there is a transcendent order that stands in judgment over every worldly achievement and that the proper attitude of leaders of nations is one of humility before a holy God and caring concern for the disinherited and the oppressed.

The holy and living God of the Scriptures has acted decisively for the salvation of the human race through Jesus Christ. The hope of humanity rests on the kingdom of God, which is now at work in our midst and will be consummated through the coming again of Jesus Christ in power and glory. Then his universal Lordship will be revealed for all to see, and the fruits of his redemption will be assured to all who repent and believe.

Notes:

1. Friedrich Schleiermacher, On Religion trans. John Oman (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1958), p. 175.

2. Cited in Norman Pittenger, The Lure of Divine Love (New York: Pilgrim Press, 1979), pp.164–165. Note that Knitter believes interfaith dialogue should not revolve around God or Christ but around meeting the human need of deliverance from suffering. See Leslie Newbigin’s criticisms of Knitter in Newbigin, “Religious Pluralism and the Uniqueness of Jesus Christ” in J. I. Packer, ed. The Best In Theology (Carol Stream, IL: Christianity Today, 1990) (267–274), p. 269.

3. Hans Küng, “The World Religions in God’s Plan of Salvation,” in Joseph Neuner, ed. Christian Revelation and World Religions (London: Burns & Oates, 1967) (pp. 25–66), p. 52.

4. John Hick, God Has Many Names (London: Macmillan, 1980), p. 88.

5. See Matthew Fox, Original Blessing (Santa Fe, NM: Bear & Co., 1983), pp. 203–205.

6. Cited by Thomas O’Meara, Romantic Idealism and Roman Catholicism (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982), p. 20.

7. Rosemary Ruether, Womanguides: Readings Toward a Feminist Theology (Boston: Beacon Press, 1985), pp. ix–xii; Sexism and God-Talk (Beacon, 1983) pp. 21–22.

8. Cited In Stephan A. Hoeller, The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead (Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1982), p. 194.

9. Cited in Peter Stuhlmacher, Historical Criticism and Theological Interpretation of Scripture trans. Roy A. Harrisville (Phil.: Fortress Press, 1977), p. 39.

10. Ibid.

11. Many feminists also tend to associate patriarchalism with the Jewish ethos, and this accounts for their distrust of Judaism as well as historical Christianity. Susanne Heine warns that “feminist literature, which sweepingly makes ‘the Jews’ and their allegedly martial God responsible for all women’s suffering down the centuries, affords a powerful stimulus to antisemitism.” Susanne Heine, Matriarchs, Goddesses, and Images of God, trans. John Bowden (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1989), p. 166.

12. “Jews Decry Prayer Book,” The Christian Century vol. 107, no. 1 (Jan. 3–10, 1990), p. 10.

Donald G. Bloesch, Ph. D., is Professor of Theology at the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary.

Donald G. Bloesch is Professor of Theology Emeritus at Dubuque Theological Seminary. He has written numerous books, including The Future of Evangelical Christianity, The Struggle for Prayer, Freedom for Obedience, and is currently working on a seven-volume systematic theology, Christian Foundations. He lives in Dubuque, Iowa, with his wife, Brenda.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor