Opposition Leaders

The Friday Reflection by James M. Kushiner

March 12th, 2021

Phineas (Num. 25:11) Orthodox cal.

Maximilian of Theveste Martyr 295

Paul Aurelian Bishop, Brittany 575

Gregory B Rome 604 Anglican, Eastern, Lutheran cals.

Theophanes Abbot Confessor, Cyzicus 818

Alphege Bishop Winchester 951

Simeon the New Theologian 1022

D

ante Parlani was 107 when he was interviewed in the 2014 documentary My Italian Secret, which tells the story of Italians who hid Jews from the Nazis. Dante was bright and articulate, with a remarkable memory.

Before the war, Italy under the fascists did not persecute Jews. But after a visit to Italy by Hitler in 1938, they were regulated by new "Laws for the protection of the race." Police were given lists of Jewish residents and official registries noted people of the Jewish "race." Jews were not, however, deported or sent to concentration camps but lived under heavy restrictions.

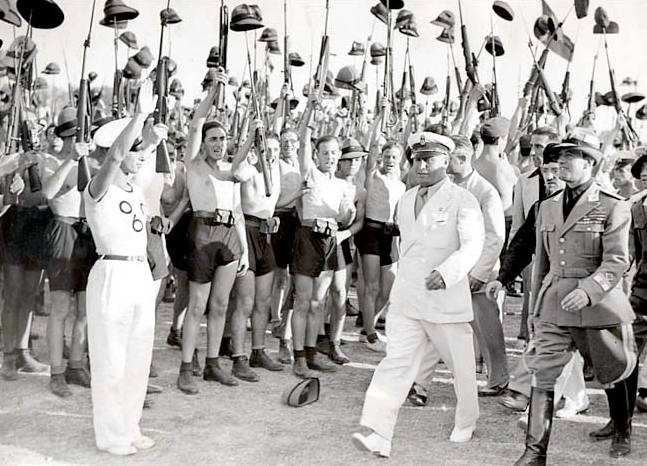

But that changed five years later, after the surrender of Italian forces to the Allies on Sicily in September 1943. Mussolini fell and Italy became divided, with the north occupied by the Nazis, supported by Italian fascists, and the south open to advancing Allied forces supported by monarchists and anti-fascists.

Dante lived in Citta di Castello ("Castle Town") in central Italy under German occupation in 1943. On camera, he was approached by Ursula, an elderly Jewish woman, who had been saved in 1943 by Monsignor Benjamin Schivo, who hid her and her mother in a convent. She told Dante that she had been saved not only by the Monsignor but by the whole city. He agreed, "Many people helped." She asked, "Here in Umbria, why weren't people afraid to help Jews?" Anyone caught hiding Jews might be executed. He responded, as if the answer were obvious, "They were human beings. It's a human life. Saving a Jew...instead of watching him die..." his voice trailed off. "There are certain moments that only those who experience them can speak of. It's one thing to read history, and another to live it."

It is one thing to read about resistance, and another thing to live it. How does one prepare to be courageous? Perhaps Msgr. Schivo's example was contagious? Courage can spread.

Rome, of course, was also occupied by the Nazis, who started rounding up Jews on October 16, 1943.

Piero Terracina vividly recalls his ordeal as a boy. His father sent him to stand in line for cigarettes at a store; suddenly, his father came and grabbed him, saying, "Let's go!" They ran home as his father told him that the Germans were rounding up the Jews.

The SS had a list of names of all the Jews. There was no place to hide, but Piero's father knew a doorman, who told him of an empty apartment and handed him the keys. The doorman then hid Piero's grandparents in his own apartment. Hiding Jews could cost you your life. Piero's family was able to hide for months.

Then, on Passover, April 7, 1944, as Piero and his family were seated at the Passover Seder meal, two SS agents banged on the door and ordered them out. They had been denounced by an Italian fascist who had seen Piero's older sister that morning go shopping for the seder meal. He "tried to pick her up," but was rebuffed and followed her. The Nazis were paying 5,000 lire for information about Jews.

Piero, his parents, and grandparents were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. After getting off the train, Piero saw his mother and ran to hug her. He recalled feeling her tears wetting his face. SS guards approached with dogs and batons. She said to them, "Go away! Go away!" then turned to her son and said, "I'll never see you again." Piero lamented, "That night, of my mother, my father, and my grandfather nothing remained but smoke and ash."

Although arrested on April 7, 1944, Piero claimed that the journey to Auschwitz began in 1938 when the "Racial Laws" were passed. The fascist state classified people by race, which put the Jews on "the edge of the abyss." "The indifference of the people," many of whom were opposed to the laws but did not oppose them, allowed a new normal to fester until the Nazis could enter and push the Jews over the edge, with help from denouncers.

But just as there were consequences to the Racial Laws, there were consequences to the acts of brave men and women who opposed the Nazis. Of Italy's Jews, 80 percent survived the war. Courage made the difference. Reading about such courage is one thing, experiencing it, something else, but one must always be prepared.

Yours for Christ, Creed & Culture,

James M. Kushiner

Executive Director, The Fellowship of St. James

—James M. Kushiner is Executive Editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, and Executive Director of The Fellowship of St. James.