Fighting Men & Children

War, Baby Boom & Bust

June 15, 2018

Battle of Okinawa, April 1945.

A battalion of U.S. Marines is moving across the central portion of the island. Japanese resistance is light. They are not yet engaged in the fierce front-line fighting in the south of the island.

The battle of Okinawa began on April 1 and lasted until June 22, 1945. U.S. casualties were over 82,000—12,500 killed or missing. Japanese military casualties were 110,000 killed, including 40,000 native Okinawans conscripted by the Imperial Army into military service, included middle school boys.

Of the estimated population of 300,000 native Okinawans, 142,000 died during the battle. Among them were the conscripted soldiers plus an untold number who committed suicide at the urging of Imperial officers, who told them the Americans would rape and kill them. Grenades were provided for the suicides; some jumped to their deaths from high cliffs, taking their children with them.

In early April, on their way across the island, that Marine battalion (3rd, 5th Regiment, 1st Division) encountered some Okinawans—"mostly old men, women and children."

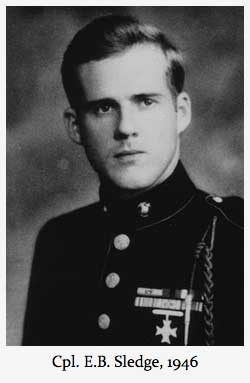

Marine Corporal E. B. Sledge wrote:

The most pitiful things about the Okinawan civilians were that they were totally bewildered by the shock of our invasion, and they were scared to death of us. . . .

The children were nearly all cute and bright-faced. . . The children won our hearts. Nearly all of us gave them all the candy and rations we could spare. They were quicker to lose their fear of us than the older people, and we had some good laughs with them. (With the Old Breed, 192-193)

Many of these Marines, including Sledge, were hardened veterans of brutal and dehumanizing campaigns, not fresh recruits easily distracted by civilian children. When the children appeared, the veterans' hearts quickened and kinder human instincts revived.

There is something universally shared across cultures when we play with children. I've seen adults meet who cannot speak the same language share in the laughter of a child who is playing peek-a-boo with the stranger. That is cross-cultural communication at its simplest. The innocence and play of children can make a bridge, a bond. They are also a sign on the path to salvation.

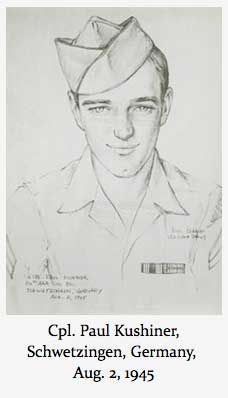

In May 1945, Sledge and company had become engaged in a brutal and deadly battle, while in Europe the Nazis surrendered and peace was secured. Members of an American anti-aircraft unit attached to the 101st Airborne, tasked with directing German prisoners of war, were invited to view the grim scene of a newly-liberated German concentration camp. My father declined to go. He had seen enough death.

In September 1945, having been awarded 5 battles stars, my father secured his discharge papers in Indian Gap, Pennsylvania, then took a train to Pittsburgh to meet his wife, who had taken a train from Detroit. They arrived at different train stations; a phone conversation with his mother-in-law finally sent him to the right station. My mother hardly recognized him, he'd lost so much weight. But he was unwounded and whole, and they were together again after 2 years and 8 months of separation.

They spent the night in a Pittsburgh hotel before heading back to Detroit. Exactly nine months later, a baby girl was born to them—on June 16, 1946, Father's Day—their first child. The baby boom was well underway.

For his part after the war, E. B. Sledge overcame psychological trauma from his combat experiences, became a professor of biology in Alabama, eventually married, and fathered two sons.

Such fathers who experienced war did not wish their children to repeat the experience. While they may have "become men" through military training and battle, it was a training that they could not easily pass on to their sons.

Sledge died in 2001; my father in 2010. Many of this "Greatest Generation," which has nearly passed away, became fathers and welcomed children as naturally and quickly as did those battle-worn Marines on Okinawa so many years ago.

The generation that followed, however, was told by a new breed of imperialists that children were a danger to them and that demographic suicide was preferable to the difficult task of raising families of more than one or two children. They were offered the implements of their own demise.

Genuine fatherhood manifests itself in welcoming and delighting in children, along with a manly determination to protect them no matter what language they speak or where they are found. If we've lost that, we've lost our humanity.

Yours for Christ, Creed & Culture,

James M. Kushiner

Executive Director, The Fellowship of St. James

—James M. Kushiner is Executive Editor of Touchstone: A Journal of Mere Christianity, and Executive Director of The Fellowship of St. James.