Unreal Liberals

The Politics of the Real: The Church Between Liberalism and Integralism by D. C. Schindler

What our deliberative, pluralistic democracy demands is that the religiously motivated translate their concerns into universal, rather than religion-specific, values. It requires that their proposals must be subject to argument and amenable to reason. If I am opposed to abortion for religious reasons and seek to pass a law banning the practice, I cannot simply point to the teachings of my church or invoke God's will and expect that argument to carry the day. If I want others to listen to me, then I have to explain why abortion violates some principle that is accessible to people of all faiths, including those with no faith at all. (Barack Obama, The Audacity of Hope)

What then-Senator Obama did here was to frame Christian opposition to abortion—and the Christian worldview more generally—as unreasonable, undemocratic, and subject to some higher, more universal order.

He managed to make it sound almost reasonable by appealing to the American sense of fair play and decorum, whereby it is understood that, whatever we personally believe about God, we should understand that not everyone shares our beliefs and that therefore it is best to keep quiet about God (let alone Jesus!) except in those private forums, such as within the four walls of our homes or our churches, where we know we are surrounded by those who share those same beliefs.

A couple things follow from behaving thus decorously. First, by rendering faith only appropriate for private forums, we make atheism the presumed American religion by default. And so, what we routinely call the secular world becomes synonymous with an atheistic world (which is ironic in a country where still fewer than five percent of Americans identify as atheist).

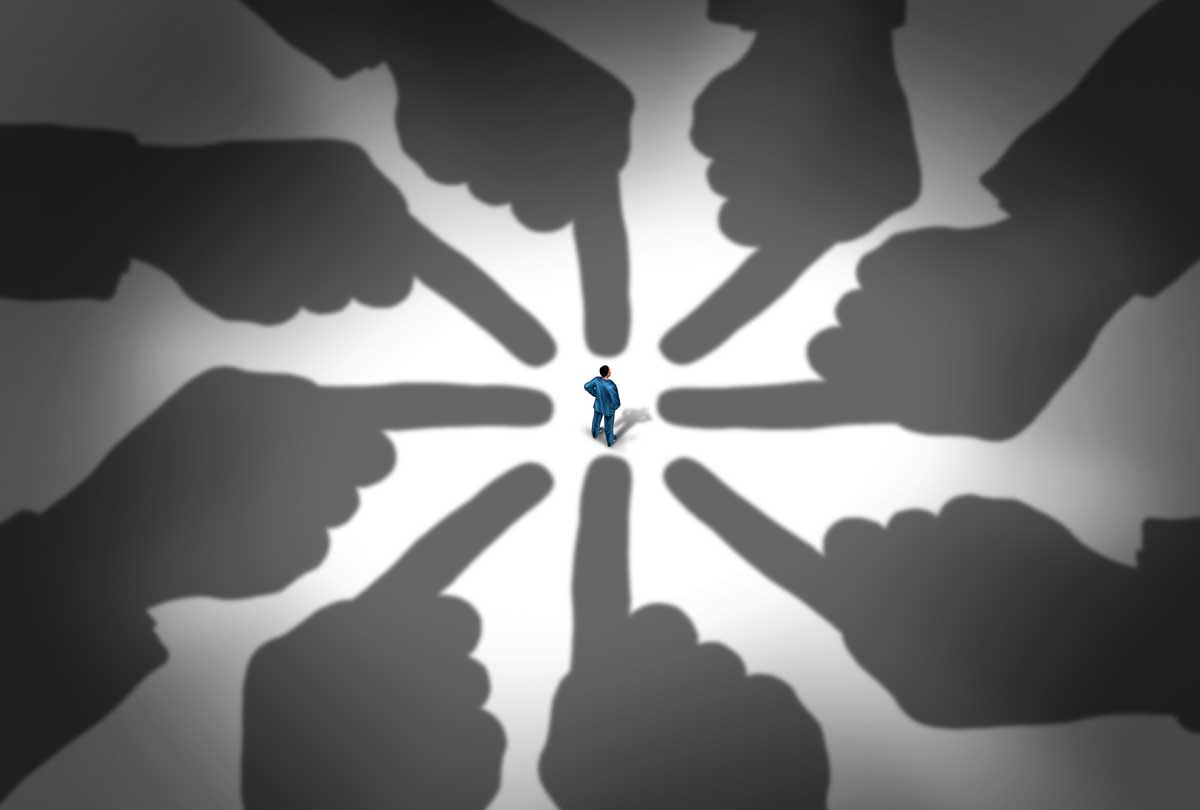

Second, as we are seeing today in the most exaggerated fashion (so far), the atheist presumption of our American decorousness has spilled over into a fear of all truth, such that we've now reached the point where even the most basic observations, such as that "a man cannot become a woman," will get you fired from almost any position in American education.

Despite numerous cancellations and destroyed lives, many still scoff at those who dare to label such actions as totalitarian. But in his epigraph for The Politics of the Real: The Church Between Liberalism and Integralism, David C. Schindler quotes Hannah Arendt to explain how our seemingly reasonable forbearance from expressing truth is the sine qua non of totalitarianism: "The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but the people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction and the distinction between true and false no longer exist."

An Optional God Is Unreal

Schindler begins his first chapter by working from a lengthy quote by Pierre Manet, who notes that it is widely believed that European political history has its foundation in Christianity and that the modern political process ever since has been one of secularization, or a steady movement away from the Church. This steady movement away from the Church, the Catholic church in particular, is, according to Schindler, the inevitable trajectory of the classical liberal tradition beginning with Thomas Hobbes.

The question "What is liberalism?" is both the title and the crux of the first chapter and of the book as a whole. Schindler says that "it is a matter of straightforward historical fact that what defines liberalism in its origins is a rejection of Christianity, specifically in the form of the Catholic Church, at least in its actual historical condition in the Middle Ages."

Well, I guess it depends on whom you ask. Catholic men such as John Courtney Murray and American Christians in general have most often looked to the Declaration of Independence when pushing back against liberalism's atheist presumptions in order to demonstrate not only that God has always been at the foundation of the American system, and that our rights are inalienable because they were given to us by God, but also as proof that there is nothing unduly or exclusively Christian about "Nature and Nature's God." On the contrary, every American can read his own ideas into this amorphous Nature and its God.

And that, says Schindler, is the problem. The classical liberal philosophical tradition dating back to the American founding "reserved a seat at the table for Christianity and appealed to God," but it was "a God defined specifically as abstracted from any . . . actual tradition so as to be potentially available to any and all of them." President Dwight Eisenhower unknowingly articulated the problem Schindler describes when he famously said, "Our government makes no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith—and I don't care what it is." But, says Schindler, "If the appeal to Nature's God means an affirmation of the right to worship whatever God one sees fit to worship, according to one's conscience or private judgement, this in fact cannot be the God who created the world . . . because one cannot choose one's creator."

Put another way, the god who is one option among many can never be the real God, and this is what Schindler is getting at in the titles of his last two books, the one under review hereand Freedom from Reality (2017). Since the God of the Bible is real, then to order our lives and our understanding of freedom around an optional god that can be whatever you want or don't want him to be (including not to be at all) is patently unreal. His thesis is an unsettling one for American conservative Christians who may never have seen a contradiction between the two things they cherish most: the God of the Bible and the classical liberalism undergirding the American founding.

An Unconvincing Case for Integralism

Schindler is hardly the first to write about the conservative contradiction. Half a century ago, in National Review, Peter Berger described the contradiction in secular terms:

Here, then, is the paradox: If conservatism has any root meaning, it is that of wanting to preserve the existing order of things. But the existing order of things in America is profoundly liberal, institutionally as well as ideologically. Thus the ideologically conservative in America, deeply critical of liberal ideology as he is, finds himself in the position of standing for the preservation of an order based on all those principles that offend him.

The difference between these two conservative writers is that where Berger was ready to throw in the towel on a conservative credo that he called "hopelessly out of date," Schindler gives no ground in his fight for the politics of the real.

In his eighth chapter, Schindler takes a deep dive into the Roman Catholic integralism movement via the writings of Edmund Waldstein, a Cistercian monk who is a key figure behind the integralist revival. Schindler describes integralism as a "thought experiment" whereby Western governments would yield to "the presence of [the Roman Catholic Church] in the formal structures of the political order." For anyone wondering how serious this is, Schindler notes that the discussion hasn't gotten much further than the Twitter postings of five or six Catholic intergralists.

Furthermore, what's the point? If this country experiences another great awakening, then Americans will vote for policies and politicians that align with their most heartfelt Christian convictions. If, on the other hand, most Americans reject the Church and regard it as immoral, then why would they ever consider granting any kind of official sanction to Christian ethical rule, let alone to the Vatican and the pope?

Consider, for example, the Amish, who live under a strict set of rules set by their church elders: they manage to do so while living in the same classically liberal country as the rest of us. Liberalism is, as far as I know, not undermining reality within the Amish community. If the Amish can maintain their fertility amid the collapsing birthrates outside their communities, we might all be Amish someday, at which point I guess we'll be a nation of Amish integralists. The point is that if we want an orthodox Christian nation, there is no need for a bunch of "ists" preaching for or against "isms." We don't need integralism; we simply need to be more Christian.

A Thrilling (but Difficult) Read

I should note that none of this is easy reading. I read the first chapter three times before attempting to say anything about it out loud. But I kept starting over simply because it was an intellectual rollercoaster, and for those who enjoy that sort of thing, Schindler is a thrilling ride (despite the potential for motion sickness). On many pages of the book, I ran out of space for margin notes.

If the intersection of classical liberalism, the common good, and the American system of government is of any interest, and if you are the kind of reader who can't pick up a book without a pen in hand, then consider this and Schindler's previous book, Freedom from Reality, The Diabolical Character of Modern Liberty (2017), as must-reads (and I would begin with Freedom from Reality). Readers who want to take Schindler's writing on a test drive can find the entire first chapter of The Politics of the Real by searching for "What is Liberalism?" at NewPolity.com.

J. Douglas Johnson is the executive editor of Touchstone and the executive director of the Fellowship of St. James.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on politics from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor