Letters of the St. Nicholas League

When Once 100,000 Children Wrote the Best Magazine That Ever Was

Some years ago, I picked up two color cartoon prints at the Chicago Printer's Row Book Fair; they appeared to have come from an old children's book. In the first of two stills on the first print, a young boy imagines himself as a crazed-looking Kaiser Wilhelm in a Daniel Boone jacket. He waves his Bowie knife in the air as he chases down a frightened grizzly bear who is running for dear life.

In the second still on the same print, a lion and a tiger both stand poised and ready to attack our crazy Kaiser, who shoulders his rifle with point-blank aim at the lion's head. Beneath the second still is the following poem:

If I should meet a grizzly bear,

You'd see him quake and run;

He'd fear my knife, my eagle-eye

And bullets from my gun.

In the second print, the boy imagines himself as a happy sailor on a rowboat in pursuit of a whale:

A roving life's the one for me

Aboard a merry whaler;

I'd dance and sing and have my fling,

I'd be a jolly sailor.

To speak of whaling as a merry life or to instill in a boy's mind a sense of adventure over the threatened slaughter of an innocent and frightened grizzly bear is so offensive and intolerable to the modern mind that I purchased and framed both prints, which have hung in the entryway to my home ever since (at the time, I tried to convince my midshipman nephew to hang the second print on his dorm room wall, but he declined this generous offer).

After carting these treasures home, I did a search on the text of the poems and discovered that the prints had appeared in a 1909 issue of St. Nicholas, a magazine for children, which I soon would come to regard as the greatest magazine ever published. One of the (very) few glories of the internet age is the ability to track down 110-year-old back issues of a children's magazine that you can then purchase for a pittance. That first eBay purchase grew into a small stack of St. Nicholas magazines that I went on to accumulate over the ensuing months.

A Sampling of St. Nicholas

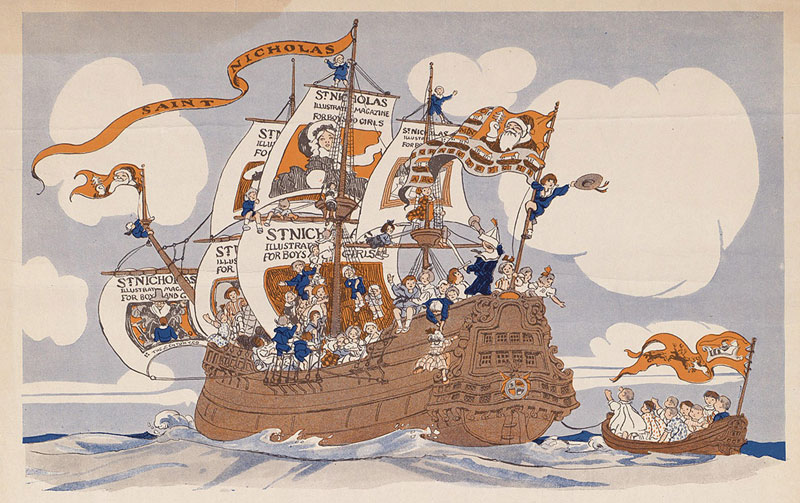

St. Nicholas was in circulation from 1873 to 1940. At its peak, in 1883, it had a circulation of 100,000, although its actual readership was some factor higher because its subscribers never actually threw their issues away, but simply passed them on to the next reader. The magazine featured illustrated serials, poems, drawings, science, history, occasional current events, and, most importantly, reader submissions.

I have the November 1899 issue open on my desk as I write. This issue begins with The Ballad of Charles Martel by William Hurd Hillyer:

Clattering up the rocky roadway, rides with wild and breathless speed

Straight to Charles' side a herald; there he checks his foaming steed,

Silent now the merry courtiers, crowding near his words to heed,"Sire, the dreaded Moorish army press on through Aquitaine;

Eudo with his stout retainers strives to check their course in vain.

All the south of France lies groaning 'neath the yoke of Moslem Spain!"

Next up is A Little Girl's Glimpse of Tennyson by Edith M. Nicholl. Nicholl's first sentence begins, "Many readers of St. Nicholas have heard of the Tennyson Memorial Cross," and nowhere in her adventurous story does Miss Nicholl see the need to explain who Alfred Lord Tennyson was, beyond referring to him as "the poet."

A little further on in the November 1899 issue is an offering for younger girls, an illustrated narrative poem, When Polly Buys a Hat. Polly shares three accounts of shopping for a hat, first with her father, then with her mother, and finally with her older sister:

When Father goes to town with me to buy my Sunday hat,

We can't afford to waste much time in doing things like that;

We walk into the nearest shop, and Father tells them then,

"Just bring a hat you think will fit a little girl of ten!"

Polly's second outing is a far more meticulous affair, as her mother fusses over hat selection and customization, but it's shopping with her elder sister that Polly dreads:

But oh, when Sister buys my hat you really do not know

The hurry and the worry that we have to undergo!

How many times I've heard her say,—and shivered when I sat,—

"I think I'll go to town to-day, and buy that child a hat!"

Polly returns home exhausted, hoping never to need another hat, although secretly happy with her sister's selection, until . . .

Then slip into the library as quiet as can be

And this is what my Brother says when first he looks at me:

"Upon—my—word! I never saw a queerer sight than that!

Don't tell me this outrageous thing is Polly's Sunday hat!"

St. Nicholas was split about equally between material for boys and material for girls. Girls (and their mothers) could pick up recipes from the St. Nicholas Cooking Club, where, naturally, every recipe appeared in metered rhyme:

Salted Almonds

If you wish to have your almonds

The daintiest in town,

Just try this way of making them

An even golden brown!First drop in boiling water,

A minute let them stand,

Then turn on the cold water,

Rub off the skins by hand.In white of egg half beaten

Roll each one carefully,

Then salt and put in oven

To crisp them thoroughly.

The St. Nicholas League

But never mind all that. Any seasoned reader of St. Nicholas knew first to turn to the back of the magazine, where he would enter the sanctum of reader submissions, known as the St. Nicholas League. This is where, against all odds, children—eligibility ended on your eighteenth birthday—might find their own letters, poems, or drawings published, and where they communed with their fellow readers. Readers whose submissions made it into the magazine competed for silver and gold badges, and even a cash prize.

St. Nicholas Leaguemembership, in a magazine with a readership well exceeding its 100,000 subscribers, was a significant achievement. E. B. White won the silver badge at age 12 and the gold badge two years later. A half-century later, White remarked that he "had not felt the need of any prize since then." The poet Edna St. Vincent Millay was a multiple gold badge winner, while submissions by William Faulkner and F. Scott Fitzgerald fell short.

The famous names listed above (and many others) appeared in every article written about St. Nicholas since about 1930, including a 1934 New Yorker memoir by E. B. White, in which he emphasized the lineup of future Pulitzer winners, novelists, and poets who once took home the silver and gold badges. "We were an industrious and fiendishly competitive band of tots," White wrote. He opened his story with a battle cry:

There is no doubt about it, the fierce desire to write and paint which we find in our land today, the incredible amount of writing and painting that still goes on in the face of heavy odds, are directly traceable to The St. Nicholas Magazine.

Well, maybe. But White's boast about the utility of the St. Nicholas League as an incubator for future greatness misses the magazine's essence, and most especially the spirit that animated the League. I did not know about its famous rosters when I first discovered the magazine, and I wasn't looking for brilliance (even if I often found it) as I spent many evenings and Sunday afternoons combing through the St. Nicholas League letters. What I found was a deep intimacy between these child writers and their magazine, which made it such an utter comfort to read. Take, for instance, the following account from A. Mabel Raitz (in iambic tetrameter, no less):

Two Points of View (1900)

Leslie an' Bubby an' Stanley, they

Come over in our yard to play,

An' Leslie took some mud 'twas there

And frowed it wite against my hair!

Nen, when I cried, my ma come out,

An' asked me what's it all about.

So nen I tell her. "Well," says she,

"You must forgive your company."

But when my pa come home, he said,

Why didn't I punch Leslie's head?

A. Mabel Raitz

Many of these child writers addressed the magazine as their "dear, dear" or "beloved friend," and that is what comes through. League members never wrote up or down to a particular audience, but always with the same excitement and honesty as they would bring to a conversation with their best friends. The only correspondent I can think of from the last century or so who ever managed, as an adult, to pull off that level of intimacy with his readers was Ernie Pyle. Consider this submission from the President of the Young Folks Morrisania Museum:

DEAR ST NICHOLAS:

I am the President of the Young Folks Morrisania Museum of Natural History, of Morrisania, of N.Y.

We formed our museum last year and have tried to succeed; the museum consists of six members all of whom are over ten and under twelve.

I like to study natural history very much.

One day last week, my brother, a member and myself were catching dragonflies in a field of high grass when we notice some black birds acting very funny; all at once we saw the male and female birds alight and then we heard a dreadful screaming and we thought we had discovered a nest. Ed (the member) and I rushed down (Ed. first) to the spot where we had seen the birds alight, and Ed. reached down to the supposed nest, and there to his astonishment about three inches from his hand was a snake stretched out; he was so frightened at his discovery that he jumped up and said, "Hurry up, Bra. a snake! a snake!" I took to my heels lively, I can tell you, and didn't stop till we had reached a rock of safety; we then got over our fright and marched out as brave as lions (with stones in our hands) to defend the birds, but the snake had run away before we reached there, and so we missed our prize.

Your constant reader, BRAINERD F.

Morrisania, NY (1885)

If you can figure out a way to work "I took to my heels lively" into conversation sometime, I promise, you and your listeners will be better for it.

Strong, True & Uncompromising

The St. Nicholas League, more than any other section of the magazine, epitomized what Mary Mapes Dodge set out to achieve when she was hired as its first editor. A proper children's magazine, she said, must not be "a milk-and-water variety of the periodicals for adults. In fact, it needs to be stronger, truer, bolder, more uncompromising than the other. . . ."

By the way, for a magazine dedicated, in part, to kindness to animals, plenty of death and killing made its way into the St. Nicholas League, especially of snakes. Here is an excerpt from William Weir's (age 12) 1908 rather matter-of-fact letter from Colorado Springs:

DEAR ST NICHOLAS:

I have taken your book two months. I thought you would like to hear the story of my killing a mountain-lion.

My father and I started at noon on the Colorado Midland Railroad and went west to Debuque, and the next morning went north to Glen Beulah Park; and that afternoon, after a hard walk, we came to a tree, and there was a mountain-lion; the dogs made an awful noise. I shot him with my 25–35 Winchester; he dropped dead; we slid him down the mountain and took him to camp; he weighed 401 pounds and his skin measured eight feet, four inches.

It wasn't until I started culling League letters for this article that I realized that William was almost certainly the twin brother of Margaret Weir, who became a League member a year earlier, and whose letter Charles Portis could have used when he created the character of Mattie Ross for his novel True Grit:

DEAR ST NICHOLAS:

I think St. Nicholas readers would enjoy hearing about New Mexico. We went on a train until we got to a place called Espinola. Then my father and brother and I got off and we went to a little hotel and stayed overnight, and the next day we went to the Indian camp.

We asked an Indian if he would go to the Cliff Dwellings; he said that he would, and we went the next day in the carriage. That night we slept on the ground, making our bed out of pine needles. The next day we started again and went where hundreds of years ago the Indians had lived, and we found the bones of an Indian and two arrowheads. The second night we slept in the Cliff Dwellings, then my brother and I went up on the top of the Hill and saw a poisonous spider under a funny Adobe brick, where an old temple had been. . . . When going to bed we heard the coyotes howl; I sprang up, grabbing our small rifle, and started out of the cave and was partway down the hill when my father rushed after me, saying that it was too dark to shoot them. So I went to bed. The next day the Indian said that there was going to be a dance. When we went to get breakfast we saw the coyotes had tried to eat up the soap. We went that day and when we got there the dance was going on. The women carried baskets and the men wore necklaces and fur ornaments. The Indians were painted black and yellow and looked very savage. And we left for home the next day.

Your new reader,

MARGARET WEIR (age 11).

Young Edward Wines of Illinois was a strict nouns and verbs man, and his letter demonstrates that ornamentation was no ticket into the League, as the editors explain in their postscript:

DEAR ST NICHOLAS:

I think some of your readers would like to hear about my three mice. Mother found a little mouse and she made him run out of the house. It sat down because it wasn't big enough to be afraid. Mother called me. I had some shredded biscuits; I gave him some. He ate it. He went down and got his little brother to eat with him. I had a box. We put the box there for the mouse. It ran out and the cat caught it. The other mouse ran in the hole. It came out again. I put him in the box. After a while another mouse came out. I put him in the box, too, and the next day they both died.

We buy the Saint Nicholas every month and mother reads it to me. I enjoy very much.

Yours truly,

EDWARD WINES (age 7)

Editor's note: This letter by a little "seven-year-old" is written in a simple, direct style that might be used as a model by some seventeen, or even seventy-year-olds who have a very roundabout way of telling a simple story.

Gassiness & Demise

Alas, by the 1930s it seemed as if the St. Nicholas League correspondents were all grown up. Their letters had sprouted adjectives and adverbs and sounded less like letters and more like creative writing pieces. And, a crime for which they should not be forgiven, League members started submitting poems written in free verse.

C. S. Lewis once explained why he decided to write children's stories, a surprising choice for a man who didn't like the company of children: "I fell in love with the Form itself: its brevity, its severe restraints on description, its flexible traditionalism, its inflexible hostility to all analysis, digression, reflections and 'gas'. . . . Its very limitations of vocabulary became an attraction." Indeed, it was these very limitations that made the St. Nicholas League letters so vivid and so intimate.

But League letters had gotten gassy by the 1930s, and it's possible that the magazine played an unintentional role in bringing this about. From its start, St. Nicholas had published an early version of word puzzles that quickly evolved into what we know today as the crossword. By the 1920s, crosswords had become a nationwide craze, and millions of Americans bought copies of Roget's Thesaurus to help solve them. And soon afterward, a lot of fifty-cent words found their way into the St. Nicholas League letters. Whether or not the thesaurus was a culprit here, the intimacy of the early years was gone.

"Is This How Adults Think We Think?"

I remember watching the CBS Evening News one evening as a young boy in the early 1970s; the topic was violence in cartoons. As they were discussing my favorite cartoon, Looney Tunes, I paid close attention to every word. One of the experts interviewed for the segment was a psychiatrist or psychologist of some sort who said that when children see Elmer Fudd shoot a shotgun at Daffy Duck's head, and the only result is that Daffy's beak spins around a few times, they will conclude that shooting someone in the head with a shotgun is harmless activity. I couldn't have been more than eight or nine years old at the time, and I remember thinking to myself, "Is this really how adults think we think?"

I still don't know the answer to my question, but we are now at least three generations into treating children as if they do think that way, and the differences that come through when reading the 100-year-old St. Nicholas letters is remarkable. Compared to their counterparts of today, those letter-writers were more like children, and yet, at the same time, they were sturdier and more imaginative. Furthermore, it is difficult to imagine many children today having the patience, let alone the hunger, for the intellectual heft that St. Nicholas pieces contained.

Below, young Neb of Oakland, California, wades gingerly into the political arena as he puts a question to the magazine's editors about the war raging in Europe. The year is 1877, and the war is between Turkey and Russia. The editors' response, like Edward Wines's mouse story, is clearer and more direct than I would expect to see in most any newspaper or cable news show today. Yes, it takes a side for "Greek Orthodox Russia" against "Mohammedan Turkey," but the editors also tell their correspondent that he mustn't think that "religious faith ever occasioned a war." Their answer is honest and direct, not because it purports to be "neutral" but because it doesn't pretend it is. Most importantly, their answer is utterly unsentimental and void of condescension.

DEAR ST. NICHOLAS:

I do not wish to make you any trouble, but I would like it very much if you could find room in some number to give a good explanation of the great war in Europe. I can't understand it in the newspaper, but I am pretty sure you can make it plain and simple enough for all your young readers.

Yours truly,

Neb.

The editors' response, in part:

The Turco-Russian war is partly a conflict of religions and partly one of politics. The Turks came into Europe as the religious emissaries of the Mohammedan religion. In all the provinces of Turkey in Europe which they conquered, the Christians of the Greek, Armenian and Catholic churches were the victims of a bitter persecution. The Czar of Russia is the head of the Greek church. He has made repeated wars in defense of the children of his faith. There have been many wars and long sieges which, like the present, were said to be only in defense of the faith of the Greek church—a crusade and a holy war.

But if "Neb" will only look at the map of Russia, he will see, if he will study climate a little, that the vast empire of Russia has one thing lacking. It has no good outlet to the Atlantic Ocean, no power upon the seas. The Baltic Sea is closed half the year by ice. . . . Russia is a prisoner as to access to the Mediterranean, and so to the Atlantic, and so to the world at large. If she is at war, she cannot float her fleets. . . . Turkey stands the tollman at the turnpike-gate, controlling and usurping the highway of all nations [to war

and trade].Maps are fascinating reading. "Neb" must not think that religious faith ever occasioned a war. Russia sincerely desires the protection of the Greek Christians in Roumania and Bulgaria in Europe, and Armenia in Asia, but she wants also to send her ships free to the winds through from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Look at the map once more, "Neb," and see how much of a great country, fertile, strong, and industrious, is closed and shut against the outer world by the absolute Turkish control of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles.

None of this went above the heads of St. Nicholas readers because they were long accustomed to reading about the rise and fall of empires, spice routes, religion, and politics.

Here is one hard story from League members in Australia, and yet, for all the suffering and distress, it is never sentimental, but as straightforward and honest an account as one would expect in a letter from a dear friend.

Sydney, New South Wales

January 7, 1885DEAR ST NICHOLAS:

We were all very much pleased to see our letter in your magazine for last March, and we all thank you very much for the kind notice you put in about it.

It is more than a year since we last wrote to you, and since then were all obliged to leave Bourke, on account of the drought; for 18 months there was no rain, and as we lived nearly five miles from the Township, we had to cart all the water from the river (Darling), as our own dam had dried up.

Father was obliged to turn out twenty valuable horses on the common to take their chance, as they could get water at the river, though the grass was all withered up. We think the poor beasts must have died, as we never heard any more about them. There was a perfect plague of flies, which stung our eyes and made them very sore. We thought our little baby brother would have lost his sight altogether, as his eyes were stung by a fly which poisoned the lids. After suffering a great deal of pain he is quite well now.

Perhaps you would like to hear about our journey down. We started out on a Monday in February, father driving us in a large buggy with four horses. We drove all day long, only resting for dinner. All the roads were covered with dead animals, horses, cattle, sheep, Kangaroos, and once we saw a dead emu. From time to time we saw flocks of thin Kangaroos and emus. Men were kept at the dams on purpose to remove the sheep as they died on going down to drink, the poor things were so weak. We saw numbers of the dead and dying on the margins of the dams. One man told us that often they had found as many as 20 sheep in the dam after one night, and they dragged them out of the water and burnt them. On many stations they chop down trees for the poor animals to eat. It was very hot and dusty driving, and often we drove all day without seeing one house. We drove till Thursday, and about noon reached Nyngan, where the Sydney Railway now extends. At 1:30 we started in the train and traveled all night, and we got to Sydney at 7:00 o'clock on a Friday morning. We were all very glad our journey was over. I must tell you that before we left Bourke our pet white cat (which we mentioned in our last letter) was drowned in the well. Father got him out at last, but he had been in the water too long before we knew of it, it was quite dead. We were all so sorry as we were very fond of him.

Our kind grandmama still sends us your magazine. The heat in Bourke was very great—120 degrees in the shade, and we were all very glad to get away.

Now, dear St. Nicholas, we must say good-bye, wishing you a happy New Year. We remain, your loving readers,

BUTTERCUP, DAISY, AND VIOLET

A Christian Magazine?

In this final tale, Mary B. tells us the story of a precocious New Jersey three-year-old named Phillip, whose story raises the question of what kind of magazine St. Nicholas really was.

Montclair, N.J., 1885

One little 3-year-old golden-hair always called his father Mr. Hay, and his mother Miss Hay. When he had been naughty, and his mother began to talk soberly to him, he would say in his most coaxing tones—"Now, Miss Hay, don't be angry to me! Be pleasant at me!"

I was a guest at his father's house, and upon my return after a few days' absence, he said to me, "Ah! Miss Mary, I was a naughty boy while you was gone away—I killed a fly and sent it to Heavon!"

He evidently shared with me my desire for letters, as he would climb upon the gate when he saw his father returning from the Post Office, and call out, "O say, Mr. Hay, has the mail-train came in yet?"

For some reason he always cried when he came to the table and found the blessing had been asked. I remember upon one of these occasions his father said to him, "Now Phillip, if you would be a good boy and not cry, you may ask the blessing yourself." With that he climbed into his highchair, folded his hands, and reverently bowing his head, and closing his eyes, perfectly ejaculated—"Oh, Lord, bless the ladies! Amen!"

M.B.

Mary Mapes Dodge named the magazine as she did because, she asked, "Is [St. Nicholas] not the boys' and girls' own Saint, the especial friend of young Americans, who [comes] as he does at a holy time?" But nowhere in the magazine's masthead, or in its publishing guidelines, or anywhere else did St. Nicholas purport to be a Christian magazine. By the measure of Christian magazines today, which make their aim explicitly known, St. Nicholas was not a Christian magazine.

And yet, as even this cursory tour makes clear, from The Ballad of Charles Martel to Tennyson's Memorial Cross, to the editors' discussion of the Turco-Russian War, to Phillip Hay's table blessing (or even Polly's Sunday hat!), it was Christian, and all the more so because it never occurred to anyone to say that it was Christian. It was, perhaps in the best possible sense, not Christian, but merely Christian.

A Bittersweet Farewell

I feel a tinge of guilt every time I look at the St. Nicholas silver badge that lies inside my living-room display cabinet, which came into my hands for a few dollars on eBay (I paid more for the shipping than I did the badge), because I know its original owner most likely soldiered through one or more rounds of disappointment before being published, let alone before winning the silver badge. I have no idea who the legitimate owner of my badge was, but I like to think it was Miss Mary Graham Bonner (b. 1891), who wrote a bittersweet farewell to her beloved St. Nicholas League in 1909:

DEAR ST. NICHOLAS:

Last month when my St. Nicholas came there was no reason which forbade me to write for the League; instead, there was every sort of reason why I should try to write. But this month, and from now on, I cannot write for the League, having reached, since the last number, the [past-eligibility] age of eighteen. It made me feel very sad, but you have done everything for me, and I think your organization is an exceptional one.

How I loved climbing the ladder! First came the hard ground with no recognition of my article. Then the first step when I beheld my name placed on the "Roll of Honor" [unpublished submissions of merit]. Then I climbed some more until you published an article of mine. Next—oh, what a lovely step that was!—the silver badge, and later the gold badge. These two prizes I love for many reasons. The last step—the top of the ladder—came quickly and was a great surprise,—the cash prize!

I cannot ever thank you enough for all you have done for me, and if I ever do succeed in achieving higher rewards, all will be due to you—the St. Nicholas League!

I wondered what did come next for young Mary. An internet search turned up her obituary, which appeared in The New York Times 65 years later, on February 13, 1974:

Mary Graham Bonner, an author of books for children, died yesterday at her home, 706 Riverside Drive. Her age was about 83, according to associates.

Miss Bonner won the 1942 Constance Lindsay Skinner Award for "Canada and Her Story," a history written for children in the United States.

Born of an old Cooperstown family, she absorbed enough of the town's baseball tradition to write many books and stories about the game. Out of consideration for masculine sensitivities, she often signed her baseball books for boys "M.G. Bonner."

Miss Bonner grew up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and graduated from the local Ladies College and Conservatory of Music. For some years she wrote the daily bedtime stories syndicated by the Associated Press.

There are no immediate survivors.

w

May you have higher rewards indeed, Mary Graham Bonner. RIP.

J. Douglas Johnson is the executive editor of Touchstone and the executive director of the Fellowship of St. James.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

14.6—July/August 2001

The Transformed Relics of the Fall

on the Fulfillment of History in Christ by Patrick Henry Reardon

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor