Paths of Resistance

Dietrich Bonhoeffer's Timely Search for a Christian Response to Nazism

Within months of his appointment as Reich Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler set in motion a policy of Gleichschaltung, loosely translated, "coordination." Audacious in its concept and breathtaking in its reach, this policy of coordination sought to bring every part of German society into alignment with the Nazi regime's racial and nationalist views.

By July of that year, the effort to establish the policy of coordination could be declared an unmitigated success. Nearly every government entity and public and private institution, including voluntary organizations, had come into alignment. Many came enthusiastically as new converts to the Weltanschauung of blood, soil, and race—the worship of the Volk—while others submitted through fear or for self-preservation. Opponents of the policy who had the means, talent, foresight, and connections to flee to other countries did so. Less fortunate opponents were either shot or interned in the first concentration camps. By August 1934, when the German military forces swore a personal oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler, the coordination of the German nation was almost complete.

Almost. Only the church remained to be co-opted.

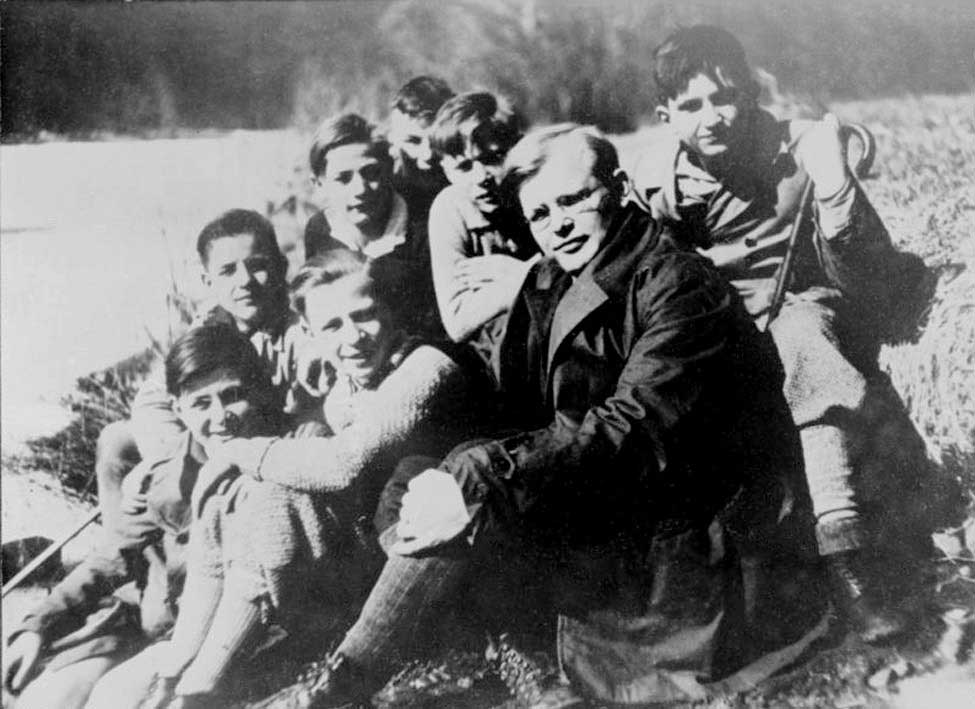

A small coterie of Christians dared to resist Nazi coordination through the creation of the Confessing Church. At the forefront of this group, and among its most zealous defenders, stood the Lutheran pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Twenty-seven years old when the policy of Gleichschaltung was first enacted, Bonhoeffer spent the rest of the 1930s rousing the church, inside and outside of Germany, to speak a "divine word" and take action against Nazi fanaticism and the "German Christians," National Socialist sycophants dressed up as Christians. Bonhoeffer displayed an unusual nimbleness as he experimented with the best means of peaceful resistance. He first looked outward to the ecumenical movement, then began flirting with Gandhian ideas of peaceful resistance, and finally turned inward to concentrate on the formation of the spiritual resources necessary to sustain the Confessing Church under persecution.

Indefatigable in his yeoman efforts to save the church and defeat the principalities and powers of racism, militarism, and jingoism, Bonhoeffer resisted to the end of a noose, where he died at the hands of Nazi henchmen in 1945. Yet, as the Scriptures teach, a seed cannot bear fruit unless it falls to the ground and dies. And so, all would not be lost at the gallows, nor victory ungrasped, as the life and writings of this saint would go on to inspire future generations of Christians to resist the evil in their day. In the inscrutable judgment of the Lord of history, success would finally come to this Christian of resistance.

Ecumenical Church Resistance

From the outset, Bonhoeffer possessed an unusual prophetic sensitivity to the evil overtures emanating from the Nazi movement. Even as the National Socialists were still accumulating power in the Reichstag, he was calling on the ecumenical movement to speak a "divine word" against the rising militarism they represented. Bonhoeffer firmly believed in the power embedded in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount to resist evil and establish peace. "Here alone [in the Sermon on the Mount] lies the force that can blow all this hocus-pocus sky-high—like fireworks," he wrote. If the "heathens" in the east—a reference to Gandhi and his followers—could grasp the shape and power of Jesus' teachings to world-changing effect, surely the church of Jesus Christ could counter the "misleader" (Verführer), Bonhoeffer's wordplay on Hitler's self-designation as "der Führer."

Bonhoeffer urged the World Alliance for Promoting Fellowship through the Churches—a multi-national ecumenical group of Protestant churches—to issue a proclamation against militarism. In his speech "The Church and the Peoples of the World," he called upon the ecumenical body to speak a "divine word" to an unsettled world, choosing Psalm 85 as his biblical text: "I will hear what God the Lord will speak: for he will speak peace unto his people, and to his saints." He implored the World Alliance to consider itself a "Church Council," an unprecedented idea.

Even before the first salvo had been fired against the Jews in Germany, Bonhoeffer promulgated a new conciliar understanding of Protestantism that could speak authoritatively to the nation of Germany, indeed to all warring nations:

When will it be that Christianity says the right word at the right time. . . . Only the one great Ecumenical Council of the Holy Church of Christ over all the world can speak out so that the world, though it gnash its teeth, will have to hear, so that the peoples will rejoice because the Church of Christ in the name of Christ has taken the weapons from the hands of their sons, forbidden war, and proclaimed the peace of Christ against the raging world. . . . There is no way to peace along the way of safety. For peace must be dared.

Like so many other efforts he made to rouse the church to rise up and act, the "divine word" he called for was never delivered. A couple of resolutions was the best the World Alliance could muster.

Confessing Church Resistance

On the heels of the Nazi party's ascension to power came the emergence of the "German Christian" movement. Dedicated to replacing everything Jewish within the Christian faith, the "German Christians" sought to conform Christianity to Nazi ideology. Their first move was to implement the "Aryan Paragraph," a piece of legislation ordering the removal of all Jewish-Christian pastors who had not served in the First World War. Bonhoeffer recognized immediately that the Aryan Paragraph was a direct attack on the very foundations of the Christian faith. As a result, he called for a status confessionis—an idea in Lutheranism that traced its origins back to the sixteenth century—which declares that a certain issue is admissible of only one proper interpretation in the church. The declaration of a status confessionis could be made if a new tenet of faith was ruled to be antithetical to the theological and doctrinal integrity of the church.

By the end of 1934, Bonhoeffer—along with Martin Niemoller and Karl Barth—had helped guide opponents of the "German Christians" into the Confessing Church. Based on his call for a status confessionis, Bonhoeffer argued that the Confessing Church was the church in Germany, declaring the Reich Church a heretical ecclesiastical body: "Whoever knowingly cuts himself off from the Confessing Church in Germany cuts himself off from salvation." He envisioned the Confessing Church as a base from which to resist Nazi ideology—specifically its anti-Semitism—and to prevent the church's complete "coordination."

Yet he foresaw that many who adhered to the Confessing Church at the outset would not remain in the fight when it intensified. With allusions to Hebrews 12:4, he began to speak of eventual martyrdom for Christian resisters:

And while I'm working with the church opposition with all my might, it's perfectly clear to me that this opposition is only a very temporary transitional phase on the way to an opposition of a very different kind, and that very few of those involved in this preliminary skirmish are going to be there for that second struggle. I believe that all of Christendom should be praying with us for the coming of resistance "to the point of shedding of blood" and for the finding of people who can suffer it through.

Sermon on the Mount Resistance

In 1935, the Confessing Church invited Bonhoeffer to develop and lead a seminary. But what kind of Christian seminary should be built? Bonhoeffer was still trying to determine the best church response to the Nazi regime. Should a traditional seminary be formed for the preparation of Lutheran pastors, or was something more needed in this dire time of "German Christians" and Nazi overlords? Should a Christian community be formed that would look more like a Gandhian Ashram, existing for the express purpose of leading a nonviolent movement to overthrow Hitler and his followers? Three years earlier he had lectured, "[The church] was destined to be, instead, the community of Jesus Christ that is within the world, yet free enough from the world to oppose secular ideologies and to do the courageous deeds required in serving others."

With these thoughts swirling in his head, he asked the Anglican priest C. F. Andrews, a confidant of Gandhi, to write a letter of introduction to the Indian leader. Gandhi's Satyagraha movement of peaceful resistance against British colonialism in India found inspiration in Jesus' teachings in the Sermon on the Mount. Might something similar be attainable in Nazi Germany? "If Pastor Bonhoeffer comes to India to enquire about what is being done for World Peace through Ahimsa and Satyagraha, I do hope you will be able to see him," Andrews wrote.

Bonhoeffer also wrote to Gandhi, expressing his plans for the church as a point of leverage against Nazism: "Only Christianity can help our western peoples to a new and spiritually sound life. . . . But Christianity must be something very different from what it has become in these days. . . . Western Christianity must be reborn as the Sermon on the Mount." Bonhoeffer sought to learn the tactics of resistance Gandhi had developed so that western Christians could "learn from you what realisation of faith means, what life devoted to political and racial peace means." He dreamed of forming a new type of pastor who could awaken those abiding comfortably in their "justified" church pews. "Following Christ—what that really is, I'd like to know—it is not exhausted by our concept of faith," he wrote from London to his friend and interlocutor Erwin Sutz as he struggled to find the right path forward.

But Bonhoeffer soon discarded Gandhi's approach, recognizing its impracticability in confronting Hitler. Gandhi's nonviolent tactics were predicated on the assumption that the oppressor could be shamed, shown his hypocrisy, and forced through public pressure to live up to his ideals. The British believed they were operating on Christian principles for the uplift and betterment of the Indian people. When it was made clear—after many protests, boycotts, and physical blows—that their policies were missing the mark and were rejected by most Indians, the British reversed course and eventually left India.

None of this was possible with Hitler, Bonhoeffer realized. Like all totalizing ideologies, Nazism was about converting people—and using force where this failed. More than one German of high standing approached Hitler believing he could change the Führer and his inner circle of ideologues. It never happened. When Bonhoeffer heard that the Christian leader Frank Buchanan, head of the Oxford Group, sought a personal audience with Hitler, he scoffed, "The Oxford movement was naive enough to try and convert Hitler—a ridiculous failure to recognize what is going on. We are the ones to be converted, not Hitler."

Discipleship as Resistance

So Bonhoeffer soon turned away from thoughts of creating peace activists to the idea of forming pastors capable of leading their congregations into resistance against the allure of Nazi anti-Jewish and nationalistic propaganda, pastors who could follow Christ "to the point of the shedding of blood." His perspective on the Sermon on the Mount turned from being the inspiration for the creation of a world-changing social movement to being the inspiration for the formation of pastors who would be able to persevere in a time of persecution. His most popular book, The Cost of Discipleship, came out of this context.

Bonhoeffer believed the key to church survival must be found in developing the right spiritual resources in church leaders. Pastors steeped in spiritual disciplines could best be formed in a quasi-monastic setting where daily meditation, Bible study, and worship were emphasized. He designed a new seminary at Finkenwalde around these spiritual lodestars.

After his other efforts to develop Christian resistance in Nazi Germany, it was in the creation of Finkenwalde that Bonhoeffer found his footing. Discipleship became the key; obedience to Christ's commands was the only sure road to resistance; faith was the catalyst. Only this approach could create the spiritual armor needed to resist Hitler's evangelizing message of racial superiority.

Daily meditation on the Scriptures was the foundation. Bonhoeffer knew whereof he spoke. During his time at Finkenwalde, he reflected on earlier days when personal ambition reigned in his life. In a 1936 letter to his former classmate, Elisabeth Zinn, he wrote:

I threw myself into my work in an extremely un-Christian and not at all humble fashion. . . . It was quite bad. But then something different came, something that has changed and transformed my life to this very day. For the first time, I came to the Bible. . . . I was not yet a Christian but rather in an utterly wild and uncontrolled fashion my own master. . . . The Bible, especially the Sermon on the Mount, freed me from all this. . . . Then came the crisis of 1933. This strengthened me in it.

Bonhoeffer taught his ordinands that daily Bible reading and memorization were the most crucial spiritual resources they possessed. He implored them to let "no day of our life in office . . . go past without our having read the Bible." Not only would this discipline safeguard the pastors against the fiery arrows of Nazi propaganda, but it would also help ground their decisions in the Word of God. Bonhoeffer had complained to Sutz as early as 1933 that in regard to the "Jewish question" even "the most intelligent people have totally lost both their heads and their Bible."

And there was something else. Scripture memorization would be indispensable to the pastors' very survival if they were placed in prison without their Bibles. "We know that it was quite a long time before some of the brothers who were arrested were given Bibles," he wrote. "Weeks like that can prove whether we have been faithful in our reading of Scripture and whether in our knowledge of Scripture we have acquired a great treasury."

For the purposes of meditation he used the Moravian Daily Texts, a devotional book he had used since childhood. As the Finkenwalde community was dispersed and its students sent to isolated pastorates, prison, and, later, the front lines of the war, Bonhoeffer reminded them to meditate each day on the Daily Texts. His circular letters to his former Finkenwalde students—masterpieces of pastoral care—encouraged them to stand strong in their difficult circumstances. Christians belong "in the midst of enemies. There they find their mission, their work," he told them. And regular meditation on the Daily Texts, especially when they were separated from each other, "keeps us in the saving community of our congregation, of our brothers and sisters, of our spiritual home."

While the Word of God was the ground of the Finkenwalde discipleship regiment, Bonhoeffer also emphasized the importance of music—a spiritual resource that had been a trustworthy balm of Gilead during the trials of his own journey. And so, he made it a mandatory part of life at Finkenwalde. In a report written in 1936, he noted, "Now as before, we spend a great deal of time and derive great joy from our music making . . . in general, I can hardly imagine our life together here without our daily music making. We have driven out many an evil spirit in this way." The brothers would find this to be even more true as they were driven into extraordinary situations that tested their resolve and commitment. In one memorable lecture given during the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, Bonhoeffer told his hearers, "The ancient Christians were still singing even as they were being thrown to the lions."

Resistance Continued

Was it all for nothing?

Even though his many futile efforts to rouse the church to action left Bonhoeffer frustrated, he never fell into despair. In his final years in prison he imagined a future where Jesus' words would fall afresh on new ears with the same arresting power as when Jesus first spoke them:

The day will come . . . when people will once more be called to speak the word of God in such a way that the world is changed and renewed. It will be in a new language, perhaps quite nonreligious language, but liberating and redeeming like Jesus' language, so that people will be alarmed, and yet overcome by its power—the language of a new righteousness and truth, a language proclaiming that God makes peace with humankind and that God's kingdom is drawing near.

Bonhoeffer was not to see a successful church resistance movement rise up against Nazi Germany. But what did not happen in his lifetime came to fruition after his death.

The legacy of his words and actions helped the church in East Germany to persevere and to create a form of resistance that ultimately witnessed the collapse of the communist regime there. What began as a prayer service in Leipzig during the early 1980s ended in the Candlelight Revolution, which brought millions of Germans out from under the yoke of communism in 1989. Not long afterward, the world witnessed the amazing reunion of West and East Germany. Bonhoeffer himself had envisioned the church someday leading the nations in reconciliation:

The "justification and renewal" of the West, therefore, will come only when justice, order, and peace are in one way or another restored, when past guilt is thereby "forgiven," when it is no longer imagined that what has been done can be undone by means of punitive measures and reprisals, and when the church of Jesus Christ, as the fountainhead of all forgiveness, justification, and renewal, is given room to do its work among the nations.

Good fruit can be garnered from Bonhoeffer's insights, experiences, and example of resistance in our own day as well, a time when political ideologies are trying to bring the church into "coordination" through cultural pressure, political enticement, and, increasingly, riotous intimidation. Suffice it to say there are ill winds blowing through our civilization.

Recognizing the "cost of discipleship" and making efforts to inculcate the spiritual resources necessary to survive in an increasingly hostile climate seem more pertinent than ever. In this situation, we must find our mission and work "in the midst of enemies," as Bonhoeffer put it.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer's words about Jesus Christ remain potent today. He would not seek credit for himself but, instead, point people to the Lord: "Christ alone adjures the false gods and the demons. Only before the cross does the world tremble, not before us."

Joseph L. Thomas is Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity at Urbana Theological Seminary. He is the founder and president of Life Together House, an organization dedicated to revitalizing American Christianity for a "world wide awake." He is the author of Perfect Harmony: Interracial Churches in Early Holiness-Pentecostalism, 1880-1909 (Emeth Press, 2014).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor