Hidden Yet Revealed

on the Martyrdom of Franz Jäggerstätter

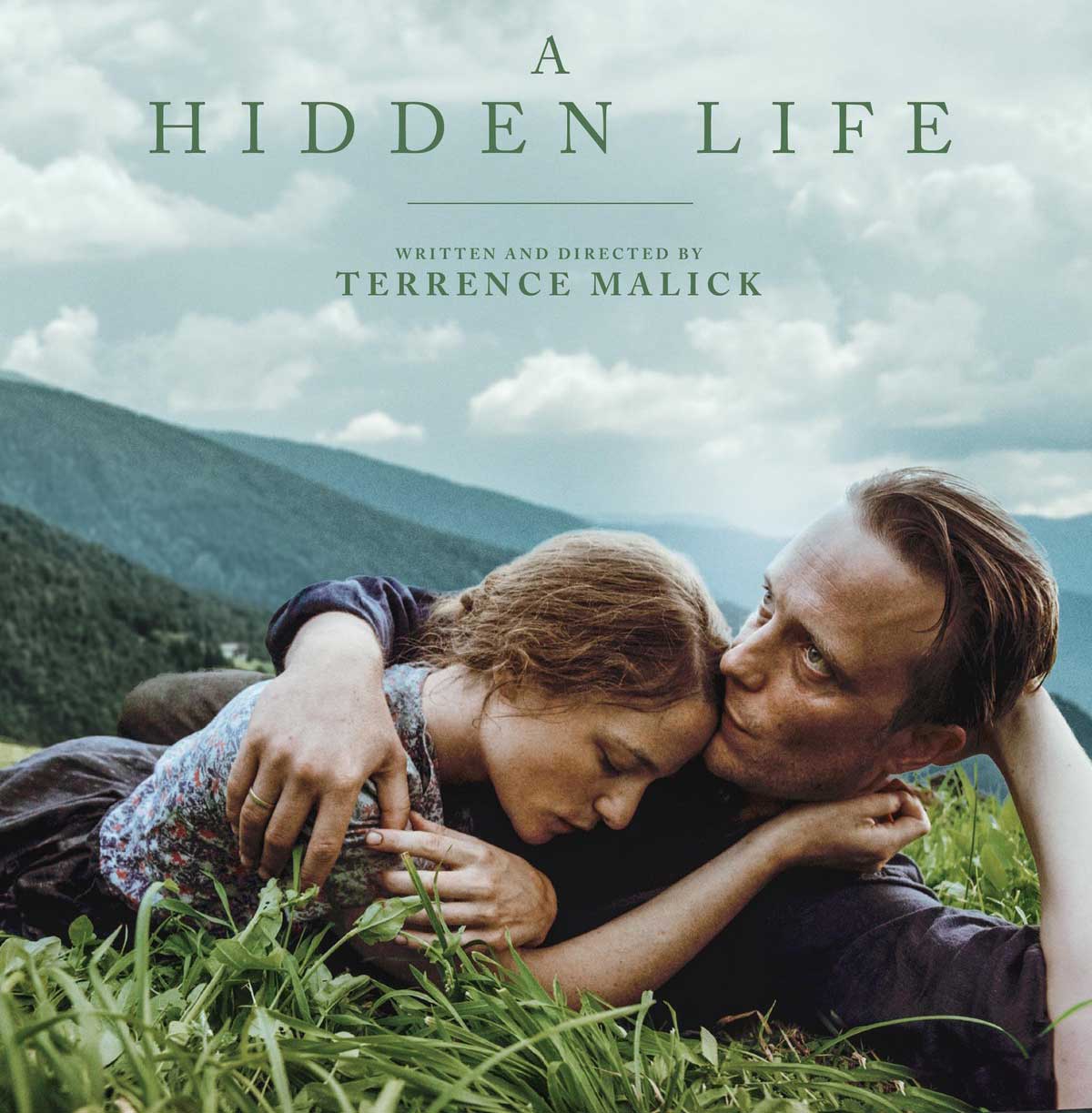

Terrence Malick's 2019 film A Hidden Life tells the story of an obscure Austrian peasant, Franz Jäggerstätter, who, by refusing to sign the mandatory pledge of loyalty to Adolph Hitler during World War II, was found guilty of undermining the German war effort and was subsequently executed. His stance against Nazi ideology and the Hitler regime not only cost him his earthly life, but also earned his wife, three daughters, and elderly mother the pain and sorrow of losing a husband, father, and son, as well as the pain of enduring social ridicule from local villagers and even fellow churchgoers.

Malick's film is tedious at points, a hallmark of his style, which weaves together a pastiche of short, choppy images meant more to evoke emotional responses than to relate biographical detail. But enough of Jäggerstätter's story comes across in these ephemeral pictures of his life, which take us from his almost idyllic pastoral existence with his wife, mother, and children; to his contentious encounters with local villagers, especially the village mayor; to his brief stint of military training at a nearby camp; and on to his open refusal to take the Hitler oath, his imprisonment in Austria, and then his final days in Berlin as an enemy of the state—days that end in a war tribunal and death sentence by guillotine.

While one can nit-pick about Malick's lack of explicitness regarding Jäggerstätter's devout Catholic faith—Jäggerstätter was pronounced a martyr of the Church by Pope Benedict XVI in 2007 and later beatified—the film makes it clear that it was Jäggerstätter's faith in Christ that made him willing to sacrifice his life and the happiness of his family for the sake of truth. One might also wonder whether martyrs are as dour and brooding as Malick makes Jäggerstätter out to be or if, as I suspect, they more often experience an overwhelming sense of joy at being able to share in Christ's sufferings.

Nevertheless, there is a particular moral dilemma that runs deep throughout the film and that Malick treats with artistic subtlety. It is a dilemma that ultimately indicts the only two Roman Catholic clergy who appear in the film, the local bishop and the priest from Jäggerstätter's village. The crux of this dilemma also underlies the movie's title, A Hidden Life, for Jäggerstätter is repeatedly tempted to abandon his defiant stance against Hitler simply because "it will not change anything in the world" and "no one will ever know about what happened."

In other words, as the various antagonists—the Nazis, village friends, some family members, and the clergy—continually point out, even if Franz's stance is right, even if it is just, and even if it is courageous, it is ultimately pointless because it will serve no practical purpose and it will go unnoticed. It won't bring about any "greater good," but it will be the cause of real harm, not only to himself but also to his family (the life of a 1940s' alpine subsistence farmer is vividly depicted by Malick, giving the viewer a crystal-clear sense of the sheer physical demands of such a life). Franz's steadfastness, like his life, will simply be lost to time.

On Not Doing Evil So Good May Come

Franz is repeatedly tempted to abandon his convictions and take the Führer's oath, for if he does, the charges will be dropped and he might even be able to serve as an orderly in a hospital rather than on the front lines. Nevertheless, he steadfastly resists these temptations. For his stance is not grounded in some kind of calculable consequence or mapped out on a pleasure-versus-pain matrix. Nor is it grounded in a moral system that might allow an evil to be done to avert harm to oneself or to achieve some greater good or higher reform. Rather, as the film increasingly makes clear, Franz is operating from an entirely different moral sensibility, one that does not make such calculations, even if the natural desire for peace, happiness, and safety constantly attend his inner life.

Jäggerstätter chooses to go to his death for the sake of not participating in an evil deed, and for the sake of maintaining the truth about the reality of intrinsic good and evil. It is because the act of swearing the oath is intrinsically evil that he refuses to do it, even though legitimate goods, particularly of family life, could be obtained if he did.

One can assume that these words of St. Paul from his Letter to the Romans would not only have been familiar to Franz, but would have sunk deep into his devout Catholic soul: "And why not do evil that good may come?—as some people slanderously charge us [the apostles] with saying. Their condemnation is just" (3:8 ESV). Here Paul makes clear that the Christian life will always be fundamentally different from other attempts at morality. The suggestion that it is okay to do evil so that good may come, even the good of divine mercy, is, he says, worthy of condemnation. For followers of Christ, no evil is necessary or condonable for the sake of achieving some greater good (leaving aside debates about just-war theory). The Christ-follower cannot do or support anything that is intrinsically evil, regardless of how objectively good the consequences might be. The temptation to act otherwise must always be resisted.

This moral posture will always put the true Christian at an earthly disadvantage with respect to the worldly-wise, for while both may desire the same end or have the same goal, the Christian will be bound by conscience to set about it only in ways that align with the will of God and are consistent with his divine laws. In this sense, the Christian's options for pursuing good are much more limited than those of his secular counterpart.

Anthony Costello holds a BA in German from the University of Notre Dame, and two master’s degrees from the Talbot School of Theology/Biola University (MA Christian Apologetics, MA Theology). An Evangelical, he also served five and a half years in the U.S. Army, with one deployment to Afghanistan. He is the founder and president of the Kirkwood Center for Theology & Ethics (kirkwoodcenter.org).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor