Feature

History's Redemption

Christ-Centered History Elevates Us All by David Thomas

Theology and history have a long and fruitful story of engagement. At the heart of the gospel is theological truth in historical embodiment, and Christians have run with that. In their modern, professional forms, though, the two fields do not engage easily. The point of difficulty is not method or topic, however; the point of separation is confessional.

History as an academic discipline is a thoroughly secular, empirical field. It requires methodological naturalism and operates entirely within time's linearity: past, present, future. It is concerned primarily with the expression of power. Christian theology must confess Christ; it cannot be secular without abandoning its reason for being. The confession of Christ leads to an entirely different vocabulary for time from the one historians use, a vocabulary that includes terms such as Christ's mode of time, Christ's hour, sinful time, redeemed time, eternity, and more. The confession of Christ also includes a commitment to love rather than to power.

Representatives from the two disciplines hail each other in a storm, bells clanging and semaphore flags waving, but in such distress at sea that communication can readily fail or is not seriously attempted. Thus, the Christian historian faces a confessional tension. Thriving as a historian requires that materialist methods be applied in all public writing and speaking. Thriving as a Christian requires that the confession of Christ infuse all aspects of life, including professional work.

I am not arguing for a mixing of the two disciplines (although each field can fruitfully inform the other.) I am arguing that the Christian confession supplants a materialist confession and thus changes our view of the past more than we might think. In particular, the Christian commitment to eternity enlarges and enriches our understanding of time and asks us to reimagine our past in ways that include the narratives of modern professional history but that also transcend them.

Balthasar on History

How radical is the disjuncture? Let's start with two central observations that the great twentieth-century theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar makes about history in his brief but provocative work, A Theology of History (1959). "The Son's action is what history is for," writes Balthasar, and "The power of giving meaning to the past is in [Christ's] hands."

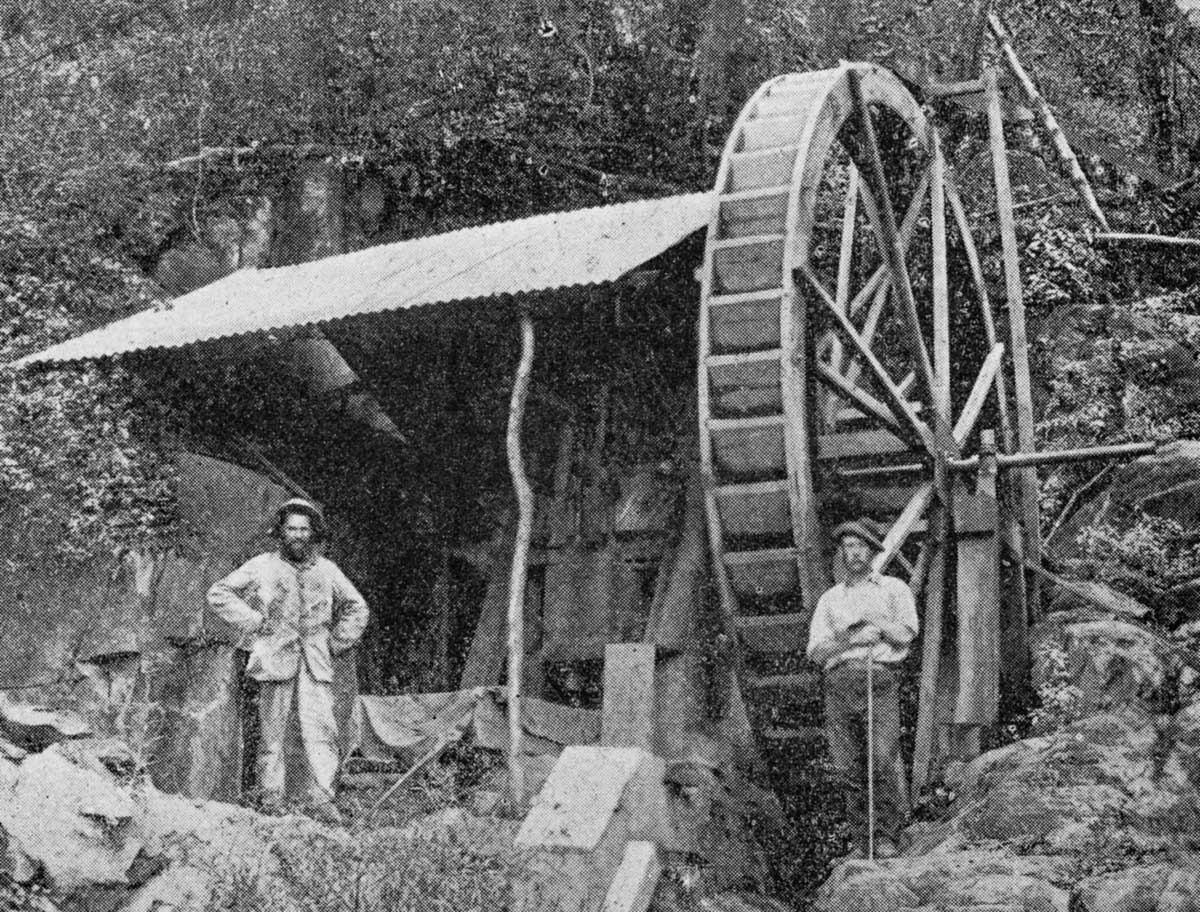

As a brief thought experiment, suppose I am writing a history of the early mining communities near Denver with an eye toward understanding how the miners lived—their food, housing, environmental commitments, violence, attitudes towards luck and hard work, and such like. As a historian, all I really want to do is tell their stories: they are interesting people who illuminate the human experience and shed light on the present. If I tell their stories well, others will think so, too, and perhaps I can make a small contribution to contemporary life. In my research I find modest drama, quiet tragedy, lots of fruitless hard work, plain folks who blew in and stuck, and a good bit of practical decision-making that now looks humorous and probably did so back then, too.

What am I to do with Balthasar's theology? It is not obvious that any of this history depends on the Son's action, awaits the Son in order to become meaningful, or is less interesting in the absence of any reference to the Son. And it's a bit off-putting to read that these poor miners were living in time that is lost or unreal or, in Balthasar's words, mere "duration leading nowhere" (although no doubt some of those miners would agree with that description of their mining days).

Balthasar's words are baffling to the historian operating within the modern, immanent frame: his outsized claims don't inspire change in purpose, methods, or conclusions. Most of us are so very used to a materialist confession when we imagine and research the past that Balthasar's arguments—tied to the confession of Christ—appear irrelevant.

And yet. And yet Balthasar (and others, stretching back through the long ages of Christian thought) argues that in Christ, time and eternity are not mutually inaccessible. Eternity provides context and meaning that are essential for understanding time and, thus, for understanding and assessing history.

There is much to consider. Let me first summarize one of Balthasar's preliminary but crucial philosophical points about time and eternity, and then turn to the Creation, Incarnation, and Eschaton, three fence posts marking off the ground that historians have been given to till. Finally, let me take a look at what this contributes to the tilling in three areas: purpose, narrative, and joy.

Preliminary Points

Balthasar opens his Theology of History with an observation about time and eternity. Much of Western thought, he notes, posits a sharp split between the "factual, singular, sensible, concrete and contingent" on the one hand, and the "necessary, universal (and because universal, abstract)" on the other. The universal offers the descriptive force of law that can determine the singular and factual, while the singular and factual are mere manifestations of the universal; thus, rational systems have been preferred by philosophers and theologians. History, committed to the unique and particular, remains in emphasis an empirical field, and happily so. Without evidence that a real person actually did something, historians have little to say.

That said, though, history is never exclusively empirical. Facts are lonely and meaningless by themselves. Even when they are neatly ordered and tell a great story,

meaninglessness cannot be abided. History constantly looks for validation and meaning in narratives and for abstractions that transcend the facts: nation, liberty, justice, identity groups, paternity, maternity, and more. As theologian N. T. Wright observes in The New Testament and the People of God (1992): "The historical project, if it is to be successful even in its own terms, must broaden its horizons."

"The more we look at history in itself," writes Wright, "the more we realize that history cannot exist by itself. It points beyond." Historians seek the watersheds and streambeds that gather facts towards a coherent narrative and then towards universality.

Karl Barth—arguably the most influential twentieth-century theologian and important to Balthasar's thought—concluded thus:

[W]e cannot overlook the fact that all history is properly and finally important and noteworthy only to the extent that it has this element [of -immediacy to God] and is thus not only historical but "non-historical." . . . we cannot overlook the fact that all historical writings become soulless and intolerable to the extent that they try to be just historical and nothing more.

Bumping Up Against Philosophy

This "non-historical" element in the study of history takes a variety of forms. Any question of purpose—why study this instead of that?—dredges up questions that transcend the topic and evidence at hand. Any question of meaning climbs a rounding path to something more than the history under study. History "may not teach us particular lessons," writes historian Gordon Wood, "but it does tell us how we might live in the world."

Historians ought not to be motivated by politics or ideology, argues historian Bernard Bailyn, because these bias the stories and impose present values on past lives. True enough: this is a commonplace. The insistence on factual evidence in support of an interpretive argument is not what makes a history great or meaningful, but what historians generally agree makes for history rather than fiction. However, this is not without its problems, for history is never strictly a matter of the past.

Historians cannot avoid their own political leaning, moral judgment, empathy, or confessional stance. Reflecting on Jefferson's response to slavery, Bailyn observes that exiling contemporary politics and ideology in favor of strict historical context provides no escape: "To the extent that you succeed [in recovering historical contexts], you can find yourself facing what is essentially a moral problem, because to explain—in depth and with sympathy—is, implicitly at least, to excuse."

Historians, like others, routinely bump up against the borders of philosophy and theology. Knowingly or not, intentionally or not, investigation into the human past draws on or assumes a particular confession about reality, knowing, and valuing: metaphysics, epistemology, and axiology. Historical study raises questions and commentary on aspects of the human experience that seem universal, or at least transcend the local contexts and perspectives of the history in question, and are suggestive of the human condition more generally.

The particular details of time, space, context, and decision—history's specialty—need the broader and sometimes universalizing contexts that other disciplines provide. Remembering the widow and the orphan is not merely an exercise in historical thoroughness, as if the entire goal were factual recall of the past. Such remembering contributes to hope, healing, and justice, all of which bear the scent of the universal.

Christ Both Unique & Normative

Where, then, does an empirical field turn for direction in the quest for the universal? And how far does the road go? Modern historians have no access to the eternal and thus tie meaning to self, ethnicity, and nation: valid and helpful to present contexts, but in truth never normative or universal. Modern history has crafted the most complete, most accurate representations of the past that the world has ever seen, but it cannot speak to the vaporousness of life or its counterpoint, the things that endure.

Speaking directly to this tension, Balthasar argues that Christ—"the existential union of God and man in one subject"—honors both the unique, singular, and contingent experiences of people and their communities, and the validity of universal, normative laws common to humanity. The Incarnation, argues Balthasar, means that the unique is the historical norm. The laws, philosophical abstractions, and theories are all reductions, diminutions. Christ's normativity shapes our understanding of individuals, communities, and their pasts; in counterpoint, Christ's particular experience informs our understanding of normativity. Historical understanding is guided by universals, and these are found in their fullest expression in the particular person of Christ.

The Claims of Eternity

Creation, Incarnation, and Eschaton are the three most intense and meaningful places in Scripture where time and eternity touch. They are, for modern disciplines, including history, impossibly problematic. As historian George -Marsden observed a few years back, modern thought silences the single most important thing to know about history: we are not our own, nor on our own. "[O]ne way to describe the history of Western thought is as a rejection of the doctrine of creation and its systematic exclusion as a consideration in academic study, outside of theology itself."

Attentiveness to the claims of eternity shifts the terms of the conversation so dramatically that either (a) the theological claims seem irrelevant (and hence not a topic for conversation), or (b) the claims of local passion and violence appear provincial. Lines from T. S. Eliot's "The Hollow Men" are suggestive:

Those who have crossed

With direct eyes, to death's other Kingdom

Remember us—if at all—not as lost

Violent souls, but only

As the hollow men

The stuffed men.

Travel to death's other kingdom—however this is interpreted—forces reinterpretation; it reveals passionate commitments to be not as passionate or vibrant or tragically lost as once thought, but hollow, stuffed, a facsimile of life. Where Christ is acknowledged as King, reevaluation follows, and devotion to anything less can appear small, forgettable, or inconsequential. Peter and Andrew drop their nets to follow him. Christian commitment to eternity (Creation, Incarnation, Eschaton) contextualizes all temporal commitments and reduces them either to their proper place in God's call to human flourishing, or to the nothingness of sin.

For historians, as for others, this is a path of humility. Rather than being of no historical value (and thus valid to deliberately silence), eternity establishes the standard by which to discern temporal meaning. The knowledge of the creative and redemptive work of Christ provides Christians with an authority, a lodestar, a love that guards against, on the one hand, trivializing human endeavor and experience and, on the other hand, absolutizing immanent authorities, ideologies, or loves.

The Fence Posts

• Creation

The Creation narrative that Christians lay claim to is personal, purposeful, and hierarchical. Scripture states that God created the world for his Son (Colossians 1:16), a remarkably personal investment that reflects the love within the Trinity. Scripture declares that people have been made male and female, in God's image, and given the job of caring for creation. This, too, is somewhat astounding and deeply personal.

The doctrine of Creation as it developed in the early Church affirmed a few main points. God and his creation are quite separate, with one entirely subordinate to the other. This creation is dependent on God's will now, had a definite beginning, and will have a definite end. These ideas have, as Marsden observed, "momentous scholarly implications."

• Incarnation

With the life of Jesus we have reached the most profound conundrum for modern thought and hence for the historian educated into modernism. We also have reached the deepest opportunities. Christians are convinced that the long course of history, most especially Jewish history, leads to the Incarnation, the one time when the Son of God came to us, born to Mary, to pitch his tent among ours. Jesus preached that the Kingdom of God was near, performed many miracles, and taught that he was, in fact, the Messiah of Jewish prophecy, the Anointed One, the Savior. This was blasphemy at a time when blasphemy was a capital offense.

After further teaching—when Jesus wanted to explain to his closest followers what his death meant, he didn't give them abstractions or a theory, he gave them a meal (both unique and normative)—he was arrested, tried, convicted, tortured, crucified, and buried. A few days later, after the Sabbath, on the first day of the week, his followers—who had seen him die—found him to be alive again with a body on this earth, a body that could be seen and felt. People talked to him, they walked dusty roads and ate meals with him, they inspected his wounds.

The Gospel accounts are not mysterious regarding the history; the events are actually quite clear. N. T. Wright's magisterial study, The Resurrection of the Son of God, exhaustively surveys the evidence for the Resurrection and the range of responses to it. He concludes that the authenticity of the evidence and its interpretation has stood up to modern scrutiny quite well. He concludes that, despite two hundred years of modern searching: "the best historical explanation for all these phenomena is that Jesus was indeed bodily raised from the dead."

The life, death, and Resurrection of Jesus are the heartbeat of Christianity. In him we meet both Lord and Christ. Without his divine authority, Christians have nothing to say, no vision of life that is distinct from other efforts to live. With him as Lord and Christ, everything changes, for redemption is possible and the new creation has begun, with a command and a model that are truly radical, truly distinct: sacrificial love is the core value, rather than power. For those who are in Christ Jesus, Paul writes, the new creation has begun (2 Cor. 5:17). It should not be any surprise that our understanding of time, eternity, and history must be reimagined and transformed, too.

• Eschaton

The Incarnation points, naturally, to eschaton. Eschatology refers to "last things" not only as the ending of temporal events but also as the culmination of what God is doing. In that sense, eschatology draws us to the point of it all, God's purposes for everything, "that which God intends to accomplish when he brings about his kingdom."

In the Eschaton, to use a metaphor from C. S. Lewis's Till We Have Faces, we get to find out where all the beauty comes from. At the heart of Christianity is the summons of divine love, a summons that is not merely temporal, but eternal and thus eschatological.

Three Avenues

Let's revisit our miners. While we've been ruminating about theology, some have drifted on or returned home, others have settled down locally doing whatever work is handy, and some have set off in yet another pursuit of that big break which most likely will never come. Others have gathered wealth and either built a company or sold their claim to one. Do our theologians—Balthasar, Wright, and Barth—help tell their story at all? Can we draw on a theology of time and eternity in ways that enhance our understanding of their stories, in ways that add truth and depth? Several avenues are worth exploring; let me pull out purpose, narrative, and joy for a closer look.

• Purpose

Return to the first observation drawn from Balthasar: that the Son's action is what history is for. Familiarity with history written and taught in recent centuries suggests a different agenda: history is not for the Son's action, but is learned and taught largely for our actions. Embedded in our histories, always, are questions of purpose and action: What is to be done? How shall we then live? How did we get here? What went wrong? Whose successes can we use as models? History offers guidance in these matters; this is a primary reason why people teach history to youth, graph histories of stock market returns, and study the effects of medicine on disease.

Even the simpler pursuits of being entertained, learning, and cultivating earnest affection include opportunities to enhance life in the present. Through historical understanding, attention is sharpened, empathy reinvigorated, and virtues recalled. This is as true for the local historian, librarian, archivist, and amateur as it is for the well-published and prominent. Historian C. L. Sonnichsen describes the buff who scours old military posts to uncover buried cartridges and buttons, rightly noting that his interest goes deeper than just buttons:

When he looks at the button, he is trying, perhaps without realizing it, to get back to that human being and share his experiences. Can anyone doubt that this is a good thing for him to do? It makes him less of a self-centered individual and more a member of society.

Plainly, Sonnichsen's buff has a more local agenda than Balthasar has, and the listed outcomes are received (sometimes unaware) more than planned. However, the two conclusions about "what history is for" are by no means diametrically opposed. Balthasar's expansive view of creation includes Sonnichsen's observation about historical understanding; the confession of Christ includes a confession of the value of all human histories. Balthasar's theology is committed to the imago Dei and to that image operating in the created order, despite sin, in ways that bring human flourishing. When Sonnichsen observes that reflection on the past carries the possibility of understanding, generates compassion for others, and helps people be more attentive to their communities, he is well within Balthasar's views.

Balthasar's commitment to creation and the imago Dei doesn't just accommodate the view that historical understanding transforms the present and promotes human flourishing; it advocates for that view. History is the story of the human past, a narrative about the changes in human societies over time, told with as much factual truth as can be learned. Given that people have been made in the image of God and live in a grace-filled creation, secular commitment to truthful historical representation will promote human flourishing. Subordinate confessions—to nation, ethnicity, rational thought, and the like—aid the work as long as they remain subordinate and refuse the temptation to usurp the confession to Christ. Such is the nature of the created order.

Our hard-rock miners of the Front Range—as part of Creation, they are worthy of study in their own right, with no moral lesson, political agenda, or national myth needed as justification. We might make connections to larger regional or national stories, for those stories also have their own intrinsic worth; however, their narratives alone are enough. We can freely wonder, grieve, and take pleasure in the local stories, for the unique and particular has its Incarnate Champion. Finally, we need not—cannot—dismiss them as damned, lost, or inconsequential to the story as a whole, because the Eschaton pulls all the lines together and we do not know the end. Scriptural examples abound: Ruth, for one, testifies to the power of an inconsequential life. We must not bear false witness.

Balthasar's vision of time and eternity offers tremendous validation for investigation into the history of human societies of any era. The creation mandate to care for what God has made directly supports all manner of learning, formal and informal. The incarnate Christ establishes the value of the unique and the particular.

Christ's drawing all things to himself in the Eschaton, likewise, offers hope that our faithful work will find its place in the redemption to come. Experimental investigation, historical research, and rational thought are not just allowed for; they are an important aspect of being good stewards. In Wright's words: "The robust Jewish and Christian doctrine of the resurrection, as part of God's new creation, gives more value, not less, to the present world and to our present bodies." And, by extension, to others and hence to human history. Such is the contribution of a robust doctrine of Eternity: Creation, Incarnation, Eschaton.

• Narrative

Christian commitment to a particular view of time and eternity—especially to those three most important points where time and eternity join hands—clarifies the narrative of human history. Most obviously, we date our calendar from the Incarnation because this date defines Anno Domini, the Year of the Lord, the starting point of the new covenant. This may be taken emblematically as a symbol of the whole, for the importance goes far beyond just a convenient zero point for our calendar.

The life of Christ clarifies the purpose of history by revealing the narrative of the Son's action. It places the covenants, the history of Israel, creation itself, and the Fall in their place in the story of God, confirming the tradition and interpretations that preceded his Incarnation and providing assurance that history proceeds in a long arc from creation and fall to final redemption.

The narratives that we perceive, organize, and teach are small fragments of the larger narrative, and that larger history promises that the broken pieces of our shorter histories are not in vain and will be gathered up. Into the midst of God's judgment comes the new creation, a new creation that helps us understand the old and anticipate the end.

The knowledge that God acts in history does not imply that we understand his actions or can write authoritatively about them. Nor does knowing the outline of the historical narrative encourage us to be triumphant. The meaning of events can never be fully established until the entire story is told. Indeed, as Andrew Barber suggests, we might easily contend that our job is to fight the long defeat, for the notable public triumphs are rare, hard to interpret, and do not last. Conversely, small acts of love and sacrifice can lead to disastrous personal consequences, yet be of greater and more lasting value than the triumphs of the

powerful.

History is God's judgment on a humanity cast out of his presence; nothing in that idea suggests triumph. Those who agree that the Son's action is what history is for and recognize the extended opportunities to flourish have no cause to be triumphant about the course of history overall—history, burdened with sin and death, is what the Son rescues us from.

That said, though, the knowledge that God's purpose draws all of history to a divine culmination changes the way we understand the past, present, and future. The cause of human flourishing is clarified when the idolatry of self, ethnicity, and nation is minimized and human life is viewed within the narrative of divine love that endures and redeems.

• Joy

Considering Creation, Incarnation, and Eschaton together, eternity validates the study of the past with a power and certainty that nothing else can match. If we are content to say that God made those miners on the Front Range, that Jesus came to redeem them, and that the Spirit called them to the culmination and fulfillment of the Eschaton, then it seems reasonable to learn something about their historical experience, at the very least to reach towards those commands to love our neighbors, honor our parents, and bear true witness. Eternity does not repudiate time; eternity redeems time.

That's an appropriately serious and biblical way to put it, but it misses the emotional core. It is not enough to be cognitive about this; the call is more fully human than that.

Scripture elevates our vision to the hills where all the beauty comes from. The Psalmist reminds us that the works of the Lord are resplendent: "Great are the works of the Lord, studied by all who delight in them" (Ps. 111:2). In that passage the link between reflective knowing, delight, and creation is unmistakable. Knowing is personal, real, delightful, and entirely dependent on God, who created. And this is not just a matter of cognition or dogma, as Robert Capon writes in The Supper of the Lamb:

In a general way we concede that God made the world out of joy: He didn't need it; He just thought it was a good thing. . . . Creation is God's living room, the place where He sits down and relishes the exquisite taste of his decoration. Things, therefore, as things, are inseparable from God, as God. Separate the secular from the sacred, and the world becomes an idol shrouded in interpretations; creation becomes too meaningful to make love to. As religion devoured life for the pagan, so significance consumes the world of the secularist. Delectability goes by the boards, dullness reigns. . . . Poor earth, poor stars, poor flesh. Without a Giver, they never become themselves.

Nor is this delight just for the here and now. Few have captured the ongoing and eschatological brilliance of doing as plainly as Capon:

Why do we marry, why take friends and lovers, why give ourselves to music, painting, chemistry or cooking? Out of simple delight in the resident goodness of creation, of course; but out of more than that, too. Half of earth's gorgeousness lies hidden in the glimpsed city it longs to become. For all its rooted loveliness, the world has no continuing city here; it is an outlandish place, a foreign home, a session in via to a better version of itself. . . . We were given appetites, not to consume the world and forget it, but to taste its goodness and hunger to make it great.

Creation and Eschaton are linked by joy and worship, and between them walks History, with its resident goodness and its longing for redemption.

Time & Eternity Walk Together

N. T. Wright concludes, "The historical project, if it is to be successful even in its own terms, must broaden its horizons." It is not that modern historical understanding is false or a waste of time, only that it is tied to a materialist confession and thus points to parts of the human experience that it specifically excludes from historical narratives. It "points beyond," concludes Wright, but cannot go there.

The expansive vision of Christianity, older, wiser, richer, and more compassionate than the modern secular ideology that partly derives from it, asks us to imagine history that points beyond, that includes but modifies and transcends the understanding offered by modern professional historical study. The contingent, particular stories of the past are deepened and recontextualized by reflection on time and eternity, by a more fully human understanding of people, and by divine purpose that is committed to redemption and joy.

The stories from our past, small or great, exist and are worth telling because the timing of the eschaton makes room for historical action, and the coming of Christ offers hope for redemption. As Balthasar argues, the Son's redemptive work is what all the historical toil and trouble are for.

Modern thought splits time from eternity and asserts that eternity has nothing to say to time, that Creation, Incarnation, and Eschaton are so far removed from the possibility of knowing that all public discussion of them should be silenced. The human person is mere nature, struggling for survival and reproduction in a conflict that ends, finally, in complete and irrevocable loss.

Balthasar, Wright, Barth, and Capon remind us that in the Incarnate Christ time and eternity walk together in the cool of the garden. The unique, historical, but also normative model for human flourishing is not to fight for, gain, and briefly possess what ultimately will be lost, but to receive and love what ultimately will be redeemed.

David Thomas is Professor of History at Union University in Jackson, Tennessee.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

14.6—July/August 2001

The Transformed Relics of the Fall

on the Fulfillment of History in Christ by Patrick Henry Reardon

more from the online archives

28.3—May/June 2015

Of Bicycles, Sex, & Natural Law

Describing Human Ends & Our Limitations Is Neither Futile Nor Unloving by R. V. Young

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor