Feature Review

Choosing the Good Portion

Rod Dreher's The Benedict Option: A Strategy for Christians in a Post-Christian Nation

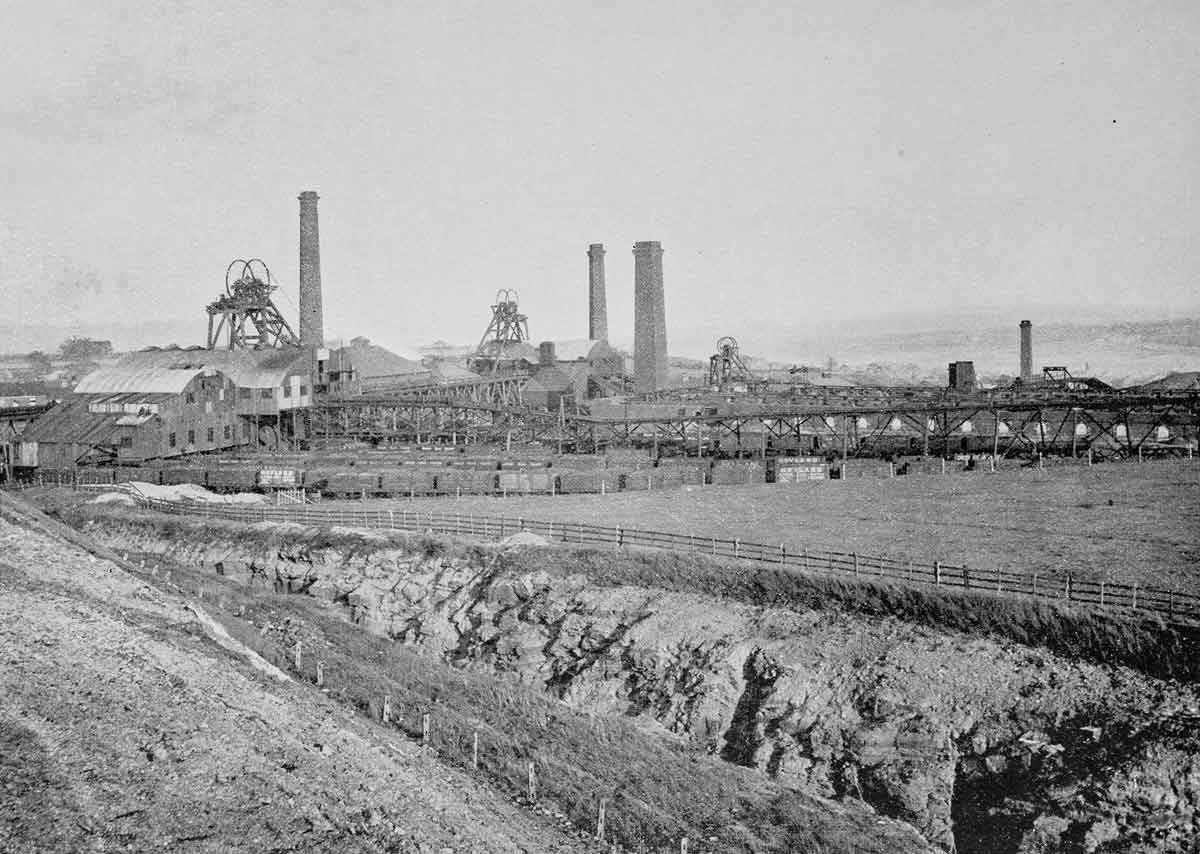

When Francis Schaeffer, the popularizer of a movement to put Evangelicalism onto a more solid intellectual footing, created his 1976 book and accompanying film series taking a longer view of the conflicts of his day, he titled it How Should We Then Live? Schaeffer was asking a question that might have seemed odd to Evangelical audiences at the time. After all, most Americans, regardless of how they did live, had not yet begun to question openly the basic moral directives of how Christianity says one should live. And many a mother in the pews would have had a sharp and pithy answer to such a question asked in isolation, with no help needed from an eccentric-looking, lederhosen-clad man. There was, however, much more to Schaeffer's question, because behind all of his work was the presupposition that his Evangelical audience didn't realize what kind of an existential threat had hit them in the 1960s and was going to go on hitting them, both in their internal theological world and in what would later become known as the culture wars.

In The Benedict Option (Sentinel, 2017), Rod Dreher asks the same basic question some forty years after Schaeffer's query, this time in a setting of what he unapologetically asserts is a time of existential threats to Christianity that are beyond anything that has been seen since the crumbling, more than a millennium and a half ago, of Roman institutions that Christianity inherited during its rapid ascendancy. Schaeffer, true to his formation, looked back to the Reformation for his answers. (I recall that when I was studying in Germany in the mid-1980s, I lent How Should We Then Live? to my agnostic Scottish flatmate, a doctoral candidate in medieval history, whose cutting response after reading it was, "If you're going to write a book that says the Reformation was good and everything else is bad, you should just say that.") For his own inspiration, Dreher looks back to the sixth-century St. Benedict of Nursia, whose Rule came to dominate all of monastic life in Western Europe.

Escape or Preservation?

While a Protestant reading the title might wonder otherwise, The Benedict Option is an ecumenical book in the best sense of the word, written for Protestants, Roman Catholics, and Orthodox alike. Part of this is because the author himself has an eclectic background, growing up in a mainline Protestant world in Louisiana, converting to Roman Catholicism as a young man, then coming to embrace Orthodox Christianity in more recent years—with each step on the journey seeming to be prompted by positive motivations rather than reactions against what came before. But perhaps more than any personal factors, it is the times themselves that drive Dreher's broadly catholic approach. For those who would be faithful to Christianity, the comforts of camaraderie can be hard to find, and kinship must be clung to wherever it can be found.

From the start, Dreher doesn't mince words about what he thinks is at stake, nor does he temper a sense of urgency in addressing it. In the introduction, he notes that Christ "did not promise that Hell would not prevail against His church in the West." Even stronger words: "There are people alive today who may live to see the effective death of Christianity within our civilization." And, "barring a dramatic reversal of current trends, it will all but disappear entirely from Europe and North America. This may not be the end of the world, but it is the end of a world, and only the willfully blind would deny it."

Some of the early critics of the concept of Dreher's "Benedict Option" reacted against what they saw as a "head for the hills" mentality. Such criticisms have provoked a strong, even irritable, response from Dreher, who correctly points out that he is advocating no such thing. In fairness to said critics, though, if one chooses to name one's proposal after a monk who quite literally fled Rome for the Apennine Mountains at the close of the fifth century to live in a cave (and when one of your chapter subheadings is entitled "Turn your home into a domestic monastery"), an author should perhaps be prepared to take such critiques in stride. Presumably, the potential distractions of choosing someone like St. Benedict as a jumping off point were worth the benefits. Or maybe Dreher didn't really think that part through.

After all, the choice of St. Benedict came to the author not through an immersion in the writings of the Fathers but rather from the closing passage of a book by Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, in which he talks about the responses of "men and women of good will" who, during a period of decline and fall in their civil society, "turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium." MacIntyre concludes:

This time, however, the barbarians are not waiting beyond the frontiers; they have already been governing us for quite some time. And it is our lack of consciousness of this that constitutes part of our predicament. We are waiting not for a Godot, but for another—doubtless very different—St. Benedict.

At the heart of Dreher's "Benedict Option" is a belief that the culture war is over and traditional Christianity has lost, decisively and permanently (for the practical purposes of anyone alive today). The tide has irrevocably turned. Not only will Christians in the future lack even passive support from a Western culture that until recently was dominated by unconscious but real remnants of Christian sensibilities, but we will be actively assaulted in ways that will make it difficult for a historically recognizable Christianity to

survive:

[W]e in the modern West are living under barbarism, though we do not recognize it. Our scientists, our judges, our princes, our scholars, and our scribes—they are at work demolishing the faith, the family, gender, even what it means to be human. Our barbarians have exchanged the animal pelts and spears of the past for designer suits and smartphones. (17)

The classification of traditional Christian teachings as bigotry and "hate speech," the imposition of sweeping bureaucratic imperatives on sex and gender that are at odds with the entire preceding history of Christian thought, an increasingly aggressive intolerance in the educational system towards any views at odds with the new orthodoxies, and technological changes in reproduction that are happening without reflection, let alone debate—seeing all this and more, it is hard to argue forcefully with Dreher on this point.

His prescription: "Rather than wasting energy and resources fighting unwinnable political battles, we should instead work on building communities, institutions, and networks of resistance that can outwit, outlast, and eventually overcome the occupation."

Movements of History

If Francis Schaeffer's L'Abri approach seemed, quite literally at times, to hold that what was needed was a cozy wayside hostel in which souls lost in the storm of the 1960s counterculture could take shelter and recover spiritually until they were strong enough to make it back home, Dreher is saying that there is no "back home" anymore, at least not one capable of withstanding gale-force winds that make that earlier storm seem like a summer zephyr.

Such a dire view of Christian prospects requires some background, and Dreher gives it a shot. His chapter entitled "The Roots of the Crisis" is a well-trodden path, with variations on general themes that have been outlined by any number of Christian thinkers and apologists concerned with the crisis: the medieval world, nominalism, the Enlightenment, the savagery of the wars that opened the twentieth century. It is one of the weaker parts of the book, perhaps precisely because it has been done before—both better and worse. Still, Dreher is to be credited for not getting lost in minutiae and qualifications that would be beyond the scope of a book like this. Some readers will remain skeptical about whether there are fundamental philosophical assumptions that can make survival hard for Christians steeped only in the intellectual juices of the modern world. They won't be convinced by this chapter, but if they do find themselves convinced by the rest of Dreher's argument, the chapter will serve as a reminder that they need to read deeply in the works of traditional Christian thinkers.

Along the way, there are some gems, such as a discussion about the ideas of sociologist Philip Rieff, who said that a culture begins to die "when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals in ways that remain inwardly compelling, first of all to the cultural elites themselves." It is hard to think of a better description of the decades leading up to our own.

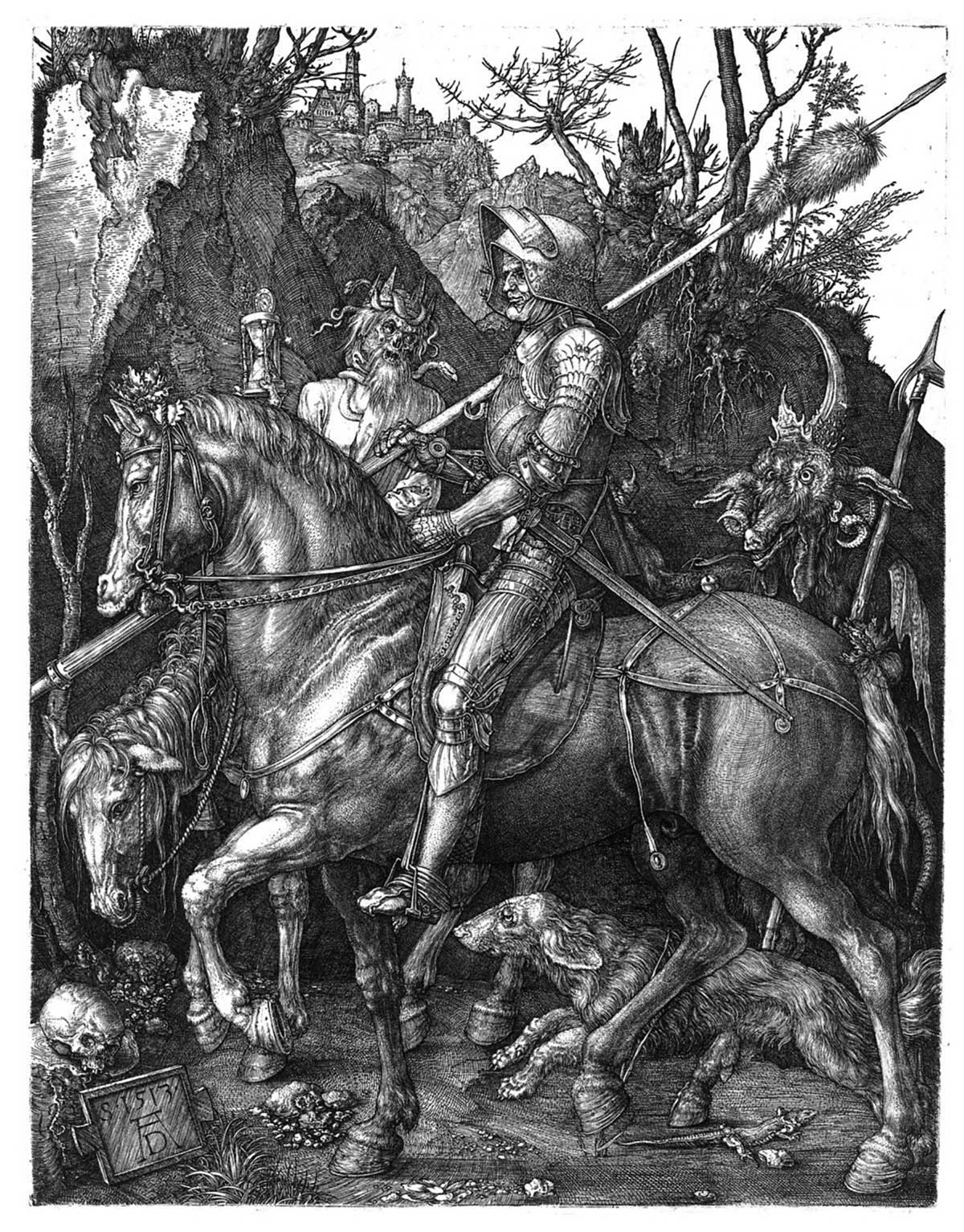

Indeed, it is this loss of self-confidence on the part of a culture that spells its doom. The world is a rough place, and to thrive in it requires courage, or at the very least, cunning laced with a bit of daring. In the context of the West, the Church itself was responsible for maintaining this self-confidence. After all, cultural elites are themselves the biggest followers of all: following each other. As long as the Church was a living spiritual presence that could not be denied, even non-pious elites went along with it and supported it. This was true in the 950s no less than in the 1950s. Some were perhaps even surprised by the fact that Christianity could change them for the better and heal them in spite of their own tepid faith. And we should not be overly restrictive in how we conceive of "elites" in this context. Church and community leaders at every level of society, down to the smallest town or congregation or parish, have found themselves sapped of will and sapped of strength by this collapse of self-confidence.

Reviving the Genius of St. Benedict

Dreher goes on to describe the Rule of St. Benedict, and the ways in which he sees that Christians of any kind could appropriate the self-conscious characteristics that made that Rule a force for preservation in the Dark Ages—not only of Christianity as a faith, but of Christian civilization itself. Regarding its emphasis on order, he writes: "To bound our spiritual passion by the rhythm of daily life and its disciplines, and to do so with others in our family and in our community, is to build a strong foundation of faith, within which one can become fully human and fully Christian."

And on through the rest: order, work, stability, community, hospitality, and balance. Dreher quotes one of the fathers at the Italian Benedictine monastery that looms large in this book: "Those who don't do some form of what you're talking about, they're not going to make it through what's coming."

To make it through, according to Dreher, we will need "Christian villages." He makes the case that unless we are in some sort of living community, the atomizing and secularizing forces of society will overwhelm us, and they will particularly overwhelm our children and young adults, choking out their spiritual and moral lives before they have a chance to begin. He sees no alternative but to be self-consciously countercultural and nonconformist—and since we are social beings, that means that we have to create our own parallel communities. Communities of like-minded Christians with a common purpose can quite literally be an actual village, or can form around a good church, a strong school, or voluntary associations and close friendships.

If we aren't together, little will happen, and instead, the places where we spend more of our time—school and work and sitting in front of screens—will dominate who we actually are. This is a part of why Dreher encourages Christians—work and life circumstances allowing—to put a priority on living closer to their churches. When people live close by, things like daily services can more readily become a part of the rhythm of life.

Sex, Liturgy & Politics

It was sadly necessary for Dreher to include an entire chapter on sex. Since so many of the hot-button issues that threaten Christian integrity today are related in some fashion to sexuality, it is a common reaction for those on the cultural left to say, "You Christians are so focused on sex!" Dreher makes the case that, far from sex being a peripheral matter to the early Church, "renouncing the sexual autonomy and sensuality of pagan culture and redirecting the erotic instinct was intrinsic to Christian culture." He quotes Sarah Ruden as saying that Christian marriage was "as different from anything before or since as the command to turn the other cheek." In short, the arena of sexuality, Dreher argues, was one in which Christians were most distinctly set apart from the pagan world in which they lived.

The encompassing moral attitudes of our own time are so pervasive that it can no longer be assumed that the faithful, especially young people, will somehow figure out what is and isn't approved by the Church, let alone why it matters so much to our spiritual well-being. This is a subject that has to be approached pastorally with tact and love, but cannot be avoided. As Dreher correctly observes, "when believers cease to affirm orthodoxy on (this) matter, they often cease to be meaningfully Christian" at all.

If there is a theme to which Dreher repeatedly returns with particular vigor, it is his condemnation of Christian involvement in politics over the last four decades. He writes: "One reason the contemporary church is in so much trouble is that religious conservatives of the last generation mistakenly believed they could focus on politics and the culture would take care of itself." And his verdict about Christian involvement in politics is that it has been a failure. While he stops just short of saying that Christians should abandon the realm of politics, his overall prescription comes close:

Here's how to get started with the antipolitical politics of the Benedict Option. Secede culturally from the mainstream. Turn off the television. Put the smartphones away. Read books. Play games. Make music. Feast with your neighbors. It is not enough to avoid what is bad; you must also embrace what is good. Start a church, or a group within your church. Open a classical Christian school, or join and strengthen one that exists. Plant a garden, and participate in a local farmer's market. Teach kids how to play music, and start a band. Join the volunteer fire department. (98)

I agree with that entire paragraph—we only have so much time and energy, and politics is, ultimately, one of the least important things in life, if one has any sort of perspective at all. But Dreher goes further: "Losing political power might just be the thing that saves the church's soul. Ceasing to believe that the fate of the American Empire is in our hands frees us to put them to work for the Kingdom of God in our own little shires" (99).

Going back to the Alasdair MacIntyre quotation, Dreher is here making a not-so-subtle correlation between the "Roman imperium" and "American Empire." It is hard to unpack everything in his argument, but I am content with saying that I am troubled by the tone and emphasis. I have largely done my own version of "seceding culturally from the mainstream," have unplugged (and as regards social media, never did plug in) from the electronic cacophony of the wired age to a degree that many today would find odd, and years ago consciously chose to disengage from my previously very active involvement in politics.

Yet I would be quite troubled if too many "men and women of good will" did the same today, and I would hold my manhood a bit cheap, to put it in Henry V terms, had I not done my own tour of duty on the political battlefield. Dreher admits that the political fight for religious liberty has importance for Christians (even if his tone implies that it is more or less already lost), but politics doesn't really work the way he seems to think it does. Meaningful influence requires comprehensive involvement. While Dreher can point to the requisite caveats in his book, one need only compare their relative tepidity with the vigor of his harsh critiques of Christian political involvement: withdrawal is Dreher's take-home message on politics. But to embrace that idea is to believe that the spread of Christianity would have played out the same way if another Diocletian, rather than Constantine, had taken the throne in the early fourth century.

Labor, Hard & Smart

In another important chapter, entitled "Preparing for Hard Labor," Dreher correctly points out that we are entering a world in which there are moral shoals in the workplace that we couldn't have imagined just a decade or two ago. "The workplace, " he writes, "is getting tougher for orthodox believers as America's commitment to religious liberty weakens." At the center of Dreher's case is the role that "diversity" on matters of sexuality is increasingly playing in corporate, government, and educational settings. Pressure is placed on employees who aren't gay or transgender to declare themselves "allies" of those who are.

Wisely, Dreher points out that "not every challenge in the workplace is a hill worth dying on," and that silence may often be a wiser and more loving approach, as opposed to being "in-your-face" about one's beliefs. Just as it is certainly true that we are kidding ourselves if we think that hard choices couldn't come our way in our particular profession or in our particular geographical location, the danger of excessive fear about particular professions and settings is that we might needlessly and prematurely close doors for ourselves.

Since I am a surgeon by profession, an example Dreher gives in this chapter particularly caught my eye. He tells of a friend of his who was a medical student but was troubled by moral and ethical choices she saw coming in her planned career path to be a medical researcher—her response was to drop out of medical school to become a hospital administrator instead. I related this story to a friend of mine who is a hospital administrator and a devout Evangelical Christian. We shared a chuckle, since we both agreed that as an administrator, he is in a far more exposed and precarious position than I am as a practicing physician—just as the engineer who knows how to run and maintain a complex power plant without burning it down is more secure in his job than is an executive in the holding company that owns it.

I make this personal observation not because I think the student made the wrong decision—it probably was the right one for her. I make it rather because I think writers, pastors, teachers, and parents should tread with great care when discouraging young people from entering a particular profession at all. As I remarked to my administrator friend, I am of the school of thought that I want "them" to have to kick me out, if my line of work is someday going to be closed to devout Christians. If they are going to cheat us, they should be made to do it to our faces, and not get to use the excuse that there aren't any Christians in a profession because none apply.

The Imperative of Classical Education

Which brings me to the broader question of education and what is perhaps the most vital section of the book. Dreher is a big proponent of a movement called classical Christian education, and I think he is right. It isn't enough to have Christian and Catholic schools, if the form and content of teaching differs little from what is in public schools. Adding a religion class and a morning prayer isn't enough anymore, if it ever was. There has to be a return to old ways of teaching and the old content that produced the great minds of the past. The fact that the classical has been seeping out of American education for nearly a century makes the task more difficult, since so much of the living tradition of that kind of education has been lost—and a living tradition, once lost, is hard to recover.

Yet as Dreher asks, "What choice do we have?" The fruits of such efforts, however imperfect at times, are obvious to those who have seen them in action. Some years back, my wife, a bit burned out after years of college teaching, accepted an invitation to teach part-time at a wonderful homeschool co-op in the city where we lived at the time. It was a traditional but "ecumenical" Christian co-op, with some parents who were serious Protestants and others who were devout Orthodox Christians. The education was broadly supportive of traditional Christian belief, yet avoided doctrinal litmus tests. It remains one of the more fulfilling things she has ever done, and the chances I got to be around those kids while they learned and grew were unforgettable. At the cathedral where I attend, there is a gem of a K–12 classical academy, dedicated to our local wonderworking saint: St. John of Shanghai and San Francisco. When I have the opportunity to be there during the week for a feast day or a Lenten service, I try to swing through the school after the Liturgy, hoping I'll have a chance to talk to some of the kids—clear-eyed, curious, and eager to engage with me about whatever they are learning. Around such life, communities can't help but form.

Dreher & Schaeffer

I began this essay by mentioning Francis Schaeffer, and I did so for a reason. I suspect that The Benedict Option will have an effect on many readers similar to the one Schaeffer's books and films had on me as a college student. They opened my eyes to things I hadn't considered, forewarned me about dangers to my faith from directions I might not have expected, helped inspire a lifelong voracious appetite for books, learning, and the life of the mind, and, in short, reassured me that there were answers out there that could allow me to keep the deep faith in which I had been reared while also having intellectual integrity.

This book, in spite of its weaknesses, will, I suspect, do something similar for a great many readers—opening eyes to the dangers to Christianity of the current and coming age here in the West, inspiring lifelong deliberate and conscious efforts to build Christian communities that are loving and mutually supportive, spurring the founding of classical Christian schools and classical homeschool co-ops, and reassuring us that yes, we really can do this, no matter how hard it may get.

Maybe a decade after I was out of college, I went back and re-watched the film series of How Should We Then Live? and picked a couple of Schaeffer's books off my shelf, and I was surprised to find them to be virtually unreadable and unwatchable—in content, argumentation, quality of writing, datedness, you name it. It wasn't just that I had converted to Orthodoxy by then, because I still delved widely and appreciatively into the writings of Protestant and Catholic thinkers alike—it was that I had read deeply in the Western Christian tradition for myself, and had moved on.

I found it hard to believe that I had been so affected by Schaeffer, and yet I had been, undeniably so—and I remained grateful. His books were for a certain place and time in our country's religious and cultural life, and for a particular setting of intellectual vulnerability from which I might not otherwise have emerged spiritually intact. I wasn't alone in how I was affected—a whole generation of conservative Protestant Christians was shaped by the same experience. It is hard to know, but I imagine others likewise shared my reaction upon returning to consider Schaeffer later in life.

The Benedict Option is a book that is going to get a lot of well-deserved press, both positive and negative. I suspect that, like Schaeffer's books, it won't hold up all that well with the passing of years. Those who are inspired by it really won't mind that, because they will by then be far down a path that changed their lives for the better.

Not to Despair

If the book deserves a warning label, it would be this: it can be easy to read about all of the alarming dangers to Christianity described in the book and to dwell on those. In spite of the earnestly delivered positive messages, inchoate anxiety lingers like a melancholy song that just won't leave one's head. In part, this is because there really are plenty of reasons for unease, and in part it is because Dreher perhaps has more of a gift for dramatically highlighting the perils that surround us than for lyrical inspiration. It would be a tragedy (and he would agree) if anyone reading the book were to be tempted to despair because the times are dark and the path seems hard to find.

Bradley W. Anderson writes from South Lake Tahoe, California. His feature article, "Kramer's Criteria," was the cover piece for the July/August 2013 issue of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on book reviews from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor