View

Carol of the Animals

Rebecca Sicree on the Burdens & Blessings of Beasts at Christmas

We should get a ferret for Christmas," my son Alec announced. I was surprised: while his younger siblings had begged for a pet, any pet, for years, Alec had seemed uninterested.

"Why do you want a ferret?" I asked.

"So we can hang our Christmas tree upside down from the ceiling," he replied. Now upside-down Christmas trees are not unknown: some medieval Germans nailed them to the rafters, just as some modern stores mount them on poles, presumably to save floor space. Alec had learned that some ferret owners use upside-down trees as well, suspending them like chandeliers, so that their rambunctious pets—which can climb but not jump—do not drink the tree water, tunnel under the tree skirt, race through the branches, tip the tree over, or eat the ornaments.

The Friendly Beasts

I was saved from both ferrets and ferret-proof Christmas trees by our landlord, who had considerately banned all pets. But I began to realize just how much animals influence how we celebrate Christmas, even for those of us who are not ferret owners. At our parish school, for example, the third-grade Christmas pageant is not complete until a succession of children wearing floppy ears crawls onstage as the class sings "The Friendly Beasts." The child in the grey sweat suit gently brays to tell you that she is the donkey; the one draped with the brown blanket sweetly hisses to tell you that he is the camel. Under his blanket is strapped a pillow, lest you mistake the friendly camel for a friendly snake.

Hissing is not the only noise camels make. It is not even their most typical noise. Camels can sound like everything from a stuttering motor to a train whistle to a cross between an elephant and a horse: they are, after all, very large animals. Fortunately for elementary teachers everywhere, most third-grade boys have no idea how unmusical camels are (nor how much they spit). Hissing is probably the only sound they make that wouldn't immediately change a reverent pageant into a slapstick comedy.

Enthroned Above the Caribou

For real comedy, however, you need reindeer. One of the high points of our school's Christmas concert, which is a bit rowdier than its Christmas pageant, is the singing of "Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer," mostly because a lucky few of the singers get to wear light-up clown noses for the song. Even without glowing noses, flying reindeer are so outlandish that we forget that little children take them seriously. We forget that to children the whole world is outlandish and mysterious. So when my daughter Teresa, who at seven had, theoretically, reached the age of reason, asked if reindeer really flew, I shouldn't have been surprised.

"No," her older brother Tom informed her. "Because if they did, you would see Eskimos flying around everywhere, and you don't."

I was heartened by nine-year-old Tom's unexpectedly logical answer, but my relief was short-lived. I soon found that he didn't so much believe that flying reindeer were impossible as that the Eskimos just didn't have any.

The Arctic appealed to Tom. "Moses," he told me later, "commanded the Israelites to make two caribou of beaten gold for the Ark of the Covenant."

"Two caribou?" I asked.

"No," Teresa corrected him, "it was two cheribou."

"Aargh!" Alec groaned. "It was two cherubim!"

Tom shrugged. "You know I can't spell." (Alas, at 22, he still can't.)

So I was left to wonder what my children really believed. Did they believe that the Lord God was enthroned above the cherubim . . . or the caribou? Caribou with wings of beaten gold? No wonder St. Nicholas with his flying reindeer seemed possible: my kids probably thought he just borrowed a team from heaven every year.

I would not have been so puzzled at my children's belief in impossible animals had I paid more attention to their father. The next Christmas Eve, there he was, out in the snow after dark, shaking sleigh bells below their bedroom windows, and hiding in the bushes when they looked out.

St. Nicholas & the Guinea Pigs

Flying reindeer, however, are not the only animals that our St. Nicholas has. He also has a white horse that he rides on December fifth, the eve of his feast day, to deliver candy in our children's shoes. And he has guinea pigs in his pockets that jump out and eat all the carrots our children leave out for his horse.

These guinea pigs used to live at our house.

The first one, appropriately, was a Christmas present.

The day had come when we finally moved and I could no longer use our landlord to protect me from ferrets. Our new lease allowed pets. And we moved just before Christmas. And my sister offered to buy our kids their first pet as a Christmas present.

I decided that the only thing that could protect me from ferrets, and ferret-proof Christmas trees, was a guinea pig.

This was not an obvious defense. Rodents, after all, do not eat ferrets: ferrets eat rodents. But that, I reasoned, was exactly the point: my children would never beg me to get one pet that would devour another one that they already knew and loved.

So we got a little guinea pig and named her Tribble, after the little alien fur balls in the 1960s Star Trek television series. In case you are not a "Trekkie," a tribble does nothing but eat, purr, and squeal at other aliens called Klingons. Now all guinea pig owners realize immediately that tribbles must be descended from guinea pigs. The only major differences between the two are that (a) guinea pigs still have vestigial legs, and (b) guinea pigs squeal at the opening and closing of refrigerator doors, there being a general dearth of Klingons in our sector of the galaxy. Also, guinea pigs, unlike tribbles, are not actually born pregnant.

This last point is not a major difference.

Sometimes life imitates art. Sometimes it even imitates Star Trek.

One morning, Tom came running into our bedroom. "Tribble has four heads!" he cried.

She didn't, of course. (This didn't even happen on Star Trek.) But it looked as if someone had beamed three full-grown hamsters into the cage with her. They were not really hamsters, of course. They were little tribbles, guinea piglets, which are born fully furred, eyes open, and ready to run. Tribble had lived up to her name.

The Moral Facts of Life

Some people say that breeding pets can teach children the facts of life. This does not work, however, if you are trying to convey the moral facts of life as well as the biological ones. This became obvious when five-year-old Maria exclaimed, "Tribble had babies! And she isn't even married!"

"Guinea pigs don't get married," I explained gently. "But there was a daddy guinea pig. He was sold to someone else at the pet store." But Maria, who obviously wanted still more baby guinea pigs, was not satisfied.

"Probably if we find another daddy guinea pig, she can have a new husband," she said, adding helpfully, "Guinea pigs don't have priests to tell them what to do." She paused. "Probably there aren't any priests who could fit into guinea pig clothes."

I tried, and failed, to picture a priest in guinea pig clothes. All I managed was a guinea pig in a Roman collar and cassock. "What," I asked weakly, "would a priest tell guinea pigs to do?"

"Probably," Maria replied, "to have only one husband."

Pigs in Pockets

The guinea pigs lived with us for several happy years, but eventually, one by one, they left us. And, one by one, they began returning on the night of December fifth, having found a posthumous career as St. Nicholas's hand-warmers. In the letter he leaves every year with the chocolate, he keeps us updated on their antics, from their visits to a prehistoric guinea pig the size of a buffalo to the complaints of his horse, whose carrots they keep stealing year after year.

Fortunately, my Christmas tree is still safe from ferrets: we now have a Chinese dwarf hamster, appropriately named Mulan, protecting us.

Barely in the Bible

Animals are so much a part of how we imagine and celebrate Christmas that we forget that they barely appear in the biblical accounts: Matthew has none in his nativity, and Luke only mentions the shepherds' flocks and the sacrificed turtledoves in passing. The beloved ox and ass only appear in the foreshadowing of Isaiah 1:3: An ox knows its owner, and an ass, its master's manger; but Israel does not know, my people has not understood. It is in the pageants and plays of Christmas that all the animals appear, most famously in the first Christmas crèche set up by St. Francis of Assisi, with a live ox and ass, in the grotto at Greccio in 1223.

The Innocence of Animals

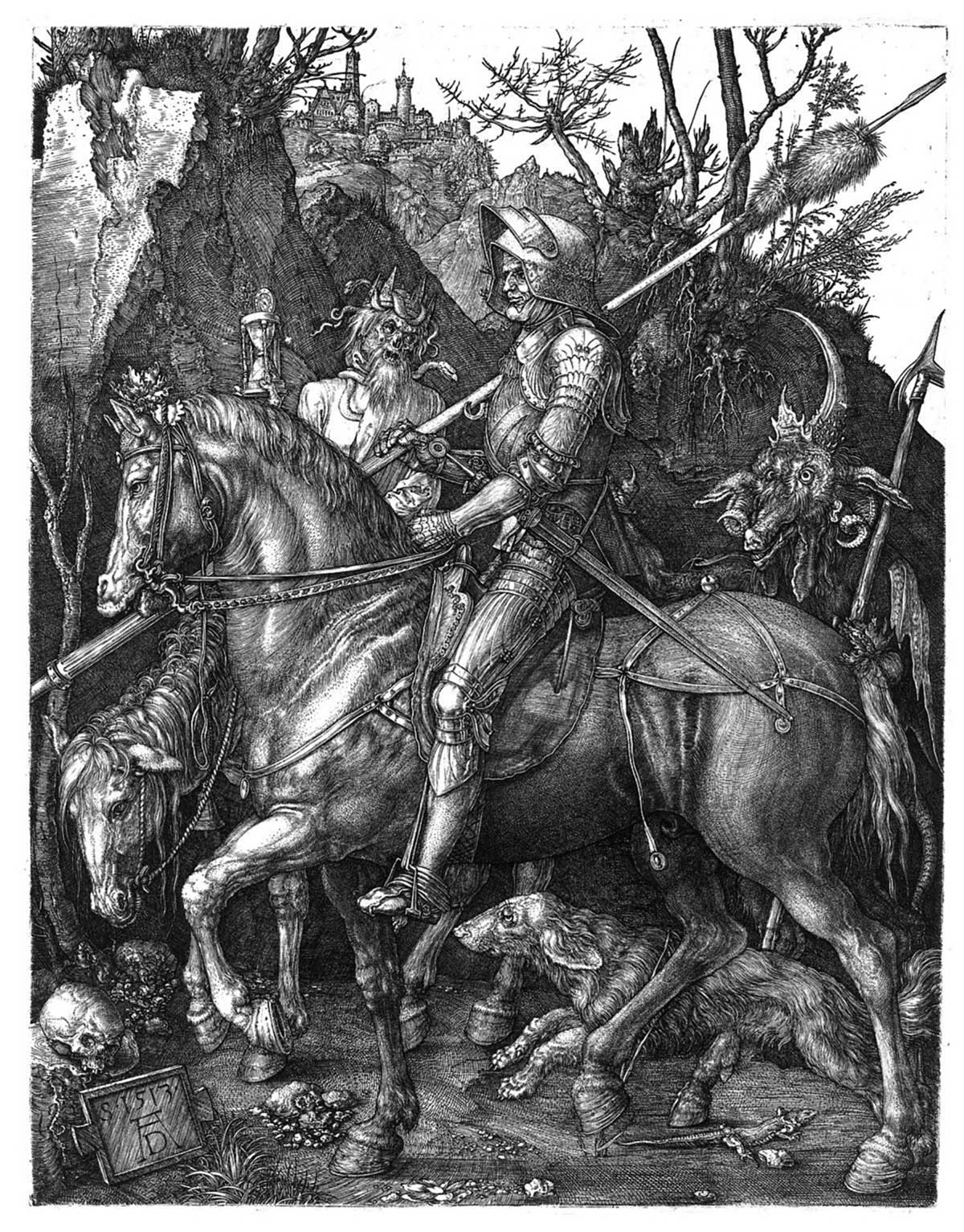

St. Francis is, of course, renowned for his love of animals, but G. K. Chesterton wrote that "the purge of paganism" had to be completed before the world could accept Francis's love of nature without mistaking it for nature worship. Maybe this is why the first crèche appeared so late in Christian history. Only when people could see a donkey and think of it bearing the Virgin Mary, instead of the satyr Silenus, could a donkey be innocent. Only then could the comic element the donkey brings with it be innocent, too.

To a Christian, man's friendship with animals is always a symbol of innocence, either the original innocence in the Garden of Eden, where the animals received their names from Adam, or the restored innocence of the Peaceable Kingdom, where the wolf will lie down with the lamb, and a little Child will lead them. Christmas pageants and crèches remind us of these ideas, and this appeal is universal: I once saw a Peruvian nativity set that had a jaguar and a tapir from the Amazon jungle paying homage to the Christ Child, right alongside the magi and the shepherds.

The Festival of the Ass

Not every Christmas tradition endures, of course, or deserves to. In thirteenth-century France, the feast of the Flight into Egypt included a procession with a donkey bearing a girl and baby to the church. The donkey was greeted with a Latin hymn, Orientis Partibus ("From the East the ass has come"), which praised "Sir Donkey" for bearing Jesus and Mary. Unfortunately, a tradition began where the congregation responded Hinham, hinham, hinham instead of Amen after the prayers. When you realize that Hinham is Latin for "Hee-haw," you can guess one reason the "Festival of the Ass" did not survive.

The song Orientis Partibus, however, continued to be sung for eight centuries. It spread to England, where Robert Davis wrote new lyrics for it in English in the 1920s.

The new carol was named "The Friendly Beasts."

The Christian Imagination

Today we live in a world that is losing the Christian imagination St. Francis helped create. None of the Christmas traditions with animals, including his crèche, are necessary to the faith, but they all help preserve the Christian imagination. And they celebrate innocence, and childhood, both of which are increasingly under attack in our world. Even a tradition that seems silly to adults can be important in this way to a child.

So when your son tries to add chariot races to your Christmas pageant (as Tom did), or your daughter dresses up as a giraffe instead of a donkey (as Isabel did), enjoy the pageantry.

And teach her to say Hinham, hinham, hinham. •

Rebecca Sicree writes from Boalsburg, Pennsylvania. She and her family attend Our Lady of Victory Catholic Church in nearby State College. She and her husband Andrew have ten children, six of whom are now adults.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor