View

The Very Idea

T. L. Jernigan on Anselm's God & the Virtue of Existing

"The more you love being, the more you will yearn for eternal life."—St. Augustine

One of the more notable works of the eleventh-century Archbishop of Canterbury, St. Anselm, is his attempt at a systematic and logical proof for the existence of God. While others have made such attempts before and after Anselm's work, his is unique, particularly in that—as a man ahead of his time—he tackled the Enlightenment-era desire to discern things "by silent reasoning in his own mind, inquir[ing] into things about which he is ignorant," while mired in the cultural and intellectual context of the high Middle Ages. In doing so, he attempted to move from the knowable to the unknowable, from the interior mind or worldly viewpoint to that of the divine.

Anselm goes on to note that he sought a single, irrefutable argument to prove that God really exists, is the height of goodness, and, while needing nothing, is needed by all. His logic has been studied by hapless college students, eager seminarians, and serious scholars for close to a thousand years; yet, in this modern era, students often find his argument unsettling, for reasons they cannot quite identify.

Anselm versus Nietzsche

Anselm's argument might be summed up (at least in its early premises) as this: God is the greatest good that can be imagined, and that which exists in reality is by its nature greater than that which exists only in the mind; thus, God must exist in reality. He praises God by saying,

[W]e believe that you are the thing than which nothing greater can be thought. . . . it is the one thing to have something in the understanding, but quite another to understand that it actually exists. . . . And certainly that than which nothing greater can be thought cannot exist only in the understanding. For if it exists only in the understanding, it is possible to think of it existing in reality, and that is greater. (from The Prayers and Meditations of Saint Anselm, Benedicta Ward, trans. [Penguin, 1973], 244–245)

Of course, this small, underlying assumption of Anselm's argument is, in its essence, the foundation for his entire ontological proof: that existence in reality is, in fact, a virtue, a greatness. Quite on the other hand, Nietzsche considered existence to be a horror inflicted upon us, and much of modernity, particularly with regard to our consideration of the unborn, seems to agree. In "Nietzsche, Virtue, and the Horror of Existence" (British Journal for the History of Philosophy, Feb. 9, 2009), Philip Kain quotes Nietzsche thus:

Oh wretched, ephemeral race, children of chance and misery, why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing.

Obviously, if one were to accept Nietzsche's bias, a virtuous deity himself could not exist, for non-existence is Nietzsche's virtue.

God's Declaration Echoed by the Church

However, Scripture and the tradition of the Church argue to justify Anselm's bias, and not that of Nietzsche or his postmodern counterpart. Creation itself is declared good at each point when, obeying the pre-existing Word, it is called forth and becomes existent in reality. Earth and sky, land and ocean, and all the creatures that dwell therein, lastly humanity itself, by being is declared good, even very good. This, Anselm would argue, is the work of a God who understands that to exist in reality not only is good, but is better than to exist in the world of ideas alone. Thus God calls creation forth to share in his existence and goodness.

While Anselm derives the existence of God in reality from the greatness of Anselm's own human existence, God appears to be working the equation in the reverse direction in Genesis 1, calling forth man to the virtue of existence from the depths of his own being and reality, saying, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. . . . So God created man in his image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them, and God blessed them" (Gen. 1:26, 27). And it was very good indeed.

The Church itself has, since its beginning, echoed the goodness of existence. Anselm's bias is in no way unique to his own argument. St. Augustine of Hippo, writing six centuries earlier, is emphatic. There were men in his own era who shared Nietzsche's bias that existence was a burden or horror from which, unable to avoid having been born, the second-best solution available to a man would be, as Nietzsche remarked, "to die soon." Responding to this idea, St. Augustine notes that,

while [the suicidal man's] error makes him believe that he will no longer be, his nature makes him wish for rest, that is to say, an increase in being. It is why, since it is impossible not to love being, the fact that we are must not be a reason for us to show ingratitude toward the goodness of the creator. (quoted in Emilie Zum Brun, St. Augustine: Being and Nothingness [Paragon House, 1988], 37)

The True Desire

It is impossible not to love being. Even in the case of an existence that might outwardly be described as a horror or burden indeed, Augustine is firm that existence itself is a virtue and that the desire is not for nothingness, but for a rest from one's labors, for a fuller existence, not a diminished one. Early Christian writers seem overwhelmingly to agree—counter to a modern worldview (and indeed its ancient counterpart) that declares that some lives, if not all lives, are a burden and a horror. Life to the Christian is clearly a blessing, a joy, a good. To exist in reality is, as Anselm proclaimed, a greatness beyond mere existence in the imagination.

Even Job, from his epic misery, proclaims the goodness of existence. Surrounded by accusing friends and encouraged by his wife to "curse God and die," Job laments every aspect of his existence before stating from the depths of his suffering,

even young children despise me; when I rise, they talk against me. All my intimate friends abhor me, and those whom I loved have turned against me. My bones stick to my skin and to my flesh [a foreshadowing of the suffering of Christ if ever there was one]. . . .

Oh that my words were written in a book. . . . For I know that my redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God, whom I shall see for myself, and my eyes shall behold. (Job 2:9; 19:18–27)

Even from the depths of his suffering, following verse after verse of what might be seen as a biblical apologetic for the worldview of Nietzsche, Job proclaims that in fact his life has value and that what is now without redemption has a redeemer who lives and will stand victorious over not only Job's own suffering but over the sin-filled, suffering earth itself.

Conflict with the Modern World

Unfortunately, modern man lives in a world that no longer knows that its redeemer lives. His suffering sits outside the context of a good creator, a fallen world, and a process of redemption. He lives in a world where the prevailing attitude is that of Nietzsche: that the best thing is simply not to exist, and even that is denied those of us who now must indeed exist. In short, he sees himself as living as a victim of "wrongful birth" (a concept that did not even exist in an age more colored by a Christian worldview) in a world where a human life may be deemed unworthy to be lived, or may be judged according to its material contribution to others or in relation to some perceived level of self-satisfaction. The prevailing view, in direct conflict with Scripture and the church fathers, is that Nietzsche was right. Herein is found the breakdown in communication with our world.

Anselm's argument unsettles the modern student because it stands in conflict with what the world around him asks him to believe. If existence, as Anselm argues, is indeed a virtue, then there is no overpopulation problem—for why would one wish to deny existence to generations yet unborn?—and there is no justification for the abortion of those who appear destined to a life of disability, struggle, and suffering. The modern student is disturbed because Anselm, in concert with a biblical worldview that declares all creation good, even very good, is calling him to look aside from the modern distractions and live a life out of sync with what is believed by those around him.

The voice of the Church is overwhelming, that existence is a virtue. Anselm's claim—that a God who is the pinnacle of goodness must in fact exist or he is less than perfect good—spills forth into human life, made in the image of God and called forth into an existence divinely labeled as good. Existence becomes, as St. John Paul II remarks in Love and Responsibility,

the first and basic good for every creature. . . . All other goods derive from this basic good. I can only act while I am. Man's multifarious works, the creations of his genius, the fruits of his holiness are only possible if the man—the genius, the saint—comes into existence.

The Right Question

The question, therefore, must shift, no longer asking which lives are worthy or worthwhile, but asking how we shall live a virtuous existence in the midst of human suffering. Abortion, which seeks to deny existence to the unborn child, and euthanasia, which seeks to enact Nietzsche's secondary proposal, to die soon, cannot be on the table for a people whose existence is indeed good. •

Tara L. Jernigan is a vocational deacon in the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) and the director of deacon formation for the Anglican Diocese of Pittsburgh. She serves on the task force for Marriage, Family and the Single Life for the ACNA and as an adjunct instructor for Trinity School for Ministry. Tara and her husband have two sons at home and one in college.

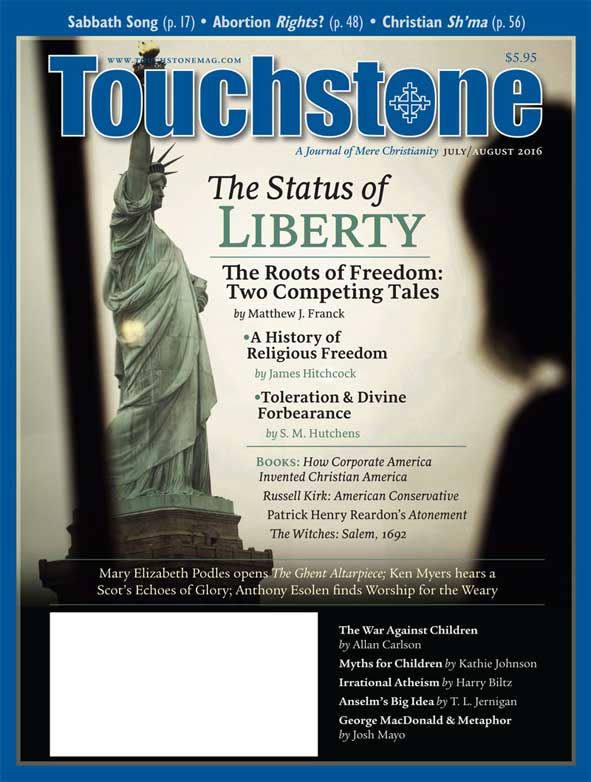

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on philosophy from the online archives

more from the online archives

14.6—July/August 2001

The Transformed Relics of the Fall

on the Fulfillment of History in Christ by Patrick Henry Reardon

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor