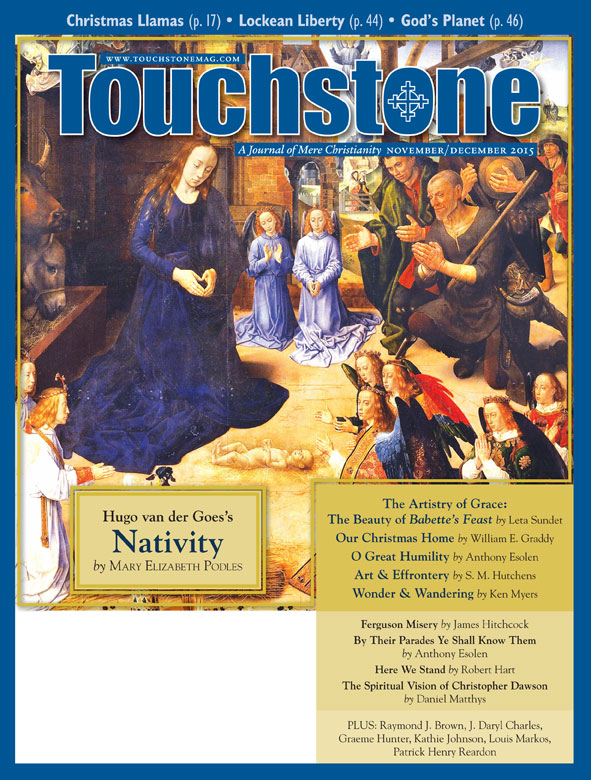

Feature

The Artistry

of Grace

The Surprising Beauty of Divine Providence in Isak Dinesen's "Babette's Feast"

When Danish short-story author Isak Dinesen (1885–1962) wrote "Babette's Feast," she was in her seventies and already dying. She had contracted syphilis from her husband early in life and likely had arsenic poisoning from the treatment. Barely able to eat, she weighed less than 80 pounds. A failed marriage and failed love affair had left her with no children; she had been nominated for but had failed to win the Nobel Prize. Malnourished and starving, under the dread necessity of making sense of her life, Dinesen wrote a story about a meal.

Luminously realistic and profoundly intricate, Dinesen's stories all celebrate physicality as something deeply spiritual. "Babette's Feast" does so in excelsis. In style it is stark but shining; in plot it is unpretentious—indeed nothing more than one long anecdote—but also a complex interweaving of characters and years. A simple story about a dinner, it is also an expansive story about the interplay of art, time, destiny, failure, and gratitude. What is more, it is a tiny masterpiece of grace.

"Babette's Feast" takes place in the small town of Berlevaag in Norway in the late 1800s, and centers around two sisters: Martine and Philippa, the daughters of the Dean of a strict Christian sect. As young women, they both were beautiful, heavenly-minded, and uninterested in marriage, but each had a failed love affair with a man from the "outside" world. Fifteen years later, the two women are still alone; the Dean their father is dead, and they struggle to hold together his splintering church.

One rainy night a fugitive Frenchwoman arrives half-dead on the sisters' doorstep. They take her in, and she lives with them for twelve years as their servant, until she wins ten thousand francs in the French lottery. She then asks the sisters for permission to cook the Dean's remaining disciples a real French dinner in celebration of his 100th birthday. The sisters warily agree and unwittingly set in motion a culinary project of wild proportions.

Some Things Are Impossible

The prelude to Babette's feast is a series of rejections in which each of the chief characters refuses some gift, some offer of grace. The story's preeminent rejection is a rejection of physicality. On page one we learn that the members of the Dean's sect have "renounced the pleasures of this world," because "the earth . . . [is] but a kind of illusion, and the true reality [is] the New Jerusalem toward which they [are] longing." The community has refused the "gift" of the present world in anticipation of a better one. Martine and Philippa similarly have a whole village of admirers but spurn earthly affection, rejecting not only physical love but also their own beauty. These rejections are to them a way of life, a way of holiness. Rejection is morally ingrained in them.

The story also describes the opposite rejection: the rejection of spiritual life. When the young officer Lorens Loewenhielm, an unabashed pleasure-seeker, sees Martine walking in the street, he has a sudden spiritual vision "of a higher and purer life . . . with a gentle, golden-haired angel to guide and reward him." Enraptured, Lorens gets himself invited to the meetings of the Dean's sect. But the more he sees and loves Martine, the more he hates himself:

[H]e loathed and despised the figure which he himself cut in her nearness. He was amazed and shocked by the fact that he could find nothing at all to say, and no inspiration in the glass of water before him. "Mercy and Truth, dear brethren, have met together," said the Dean. "Righteousness and Bliss have kissed one another." And the young man's thoughts were with the moment when Lorens and Martine should be kissing each other. He repeated his visit time after time, and each time seemed to himself to grow smaller and more insignificant and contemptible.

Lorens realizes that if he joins Martine's world, he will diminish, and he cannot bear that. When he leaves the Dean's house for the last time, he tells Martine, "I am going away forever! I shall never, never see you again! For I have learned here that Fate is hard, and that in this world there are things which are impossible." Lorens devotes himself to his career, becoming fashionable and successful. Later, he recalls the moment when, at a dinner "given in his honor at the finest restaurant in the city," a beautiful woman made eyes at him across the table; in that moment he "[saw] Martine's face before him and . . . rejected it." Lorens chooses an impressive reputation and a life of pleasure over the humiliation of love. He denies his spiritual longings.

Martine's sister Philippa makes the story's most symbolic rejection: a rejection of art. Philippa's "lover," Achille Papin, is a great Parisian opera singer who stumbles into Berlevaag one Sunday; a good and honest man, unspoiled by the "idolization of nations," he is melancholy, feeling himself "an old man, at the end of his career," and acutely aware of the vanity of his accomplishments. When he hears Philippa sing in church, he has a vision of new life; when he convinces her father to let him give her singing lessons, all his youthful confidence and optimism return. "I was wrong in believing that I was growing old," he exclaims, "My greatest triumphs are before me! The world will once more believe in miracles when she and I sing together!"

But Philippa is wary, mulling over his ecstatic predictions and pondering them in her heart. One day they sing a love duet, and Papin, overwhelmed by the music, grabs Philippa and kisses her. Philippa immediately tells her father that she doesn't want any more singing lessons. While the crushed Papin returns to France and to a dying career, Philippa slips with apparent ease back into ordinary life. But the ease is only apparent; Philippa was not simply scandalized by Papin, but "surprised and frightened by something in her own nature." Out of fear of her own desires, Philippa rejects Papin's gift of music as well as her own gift; she rejects the artist that she could be.

Philippa's rejection parallels the whole community's climactic rejection: the rejection of Babette's feast. As preparations for the French dinner escalate, Martine shares her dread with the rest of the community, warning them that for all she knows they will be participating in a "witch's Sabbath." The Brothers and Sisters promise that no matter what is set before them, "be it even frogs or snails," they will not mention it. They will not even let themselves taste it. They will "cleanse [their] tongues of all taste and purify them of all delight or disgust of the senses, keeping and preserving them for the higher things of praise and thanksgiving."Before the dinner has even been set before them, the community has already, with the best of intentions, rejected it; they have refused to let it have any effect on them—even the ordinary, desired effect of food.

All the characters behave as if they are none the worse for their rejections, as if they are content with the decisions they have made. But they are lying. In a letter to the two sisters, Papin tells Philippa that he imagines her "surrounded by a gay and loving family" while he is "gray, lonely, forgotten," acknowledging that she "may have chosen the better part in life." But this is fierce irony, whether intentional or not, because Philippa has chosen no such thing: she is just as gray, lonely, and forgotten as he. Lorens Loewenhielm, now General Loewenhielm, has "obtained everything he [has] striven for in life," but his prosperity is "jarred" by one "queer fact": he is unhappy. He has "gained the whole world," but is always "[feeling] his mental self all over, as one feels a finger over to determine the place of a deep-seated, invisible thorn." The Brothers and Sisters, dedicated to the New Jerusalem, are, as they approach it, only more and more plagued by worldly concerns.

A dying church, beautiful women grown old, great men bemoaning the vanity of their work—these images communicate the melancholy truth: no one has chosen rightly. Everyone has made the wrong decision, and—although they may have done so helplessly—refused grace.

Like a Wave Rising

In this story, grace returns suddenly and almost ominously in the form of "a massive, dark, deadly pale woman," who is "haggard and wild-eyed like a hunted animal." Babette is a "Communard" whose husband and son were both shot as revolutionaries, a fugitive who was herself arrested as a Petroleuse (fire-starter) and barely escaped France with her life. Worst of all, she is a Papist.

But as soon as she establishes herself in the sisters' home, Babette begins to move in the undercurrents of the community. Although the sisters take her in out of pity, Babette quickly becomes invaluable to them. There is something magical, almost witch-like about her abilities. As soon as she assumes the housekeeping for Martine and Philippa, "its cost [is] miraculously reduced, and the soup-pails and baskets [acquire] a new, mysterious power to stimulate and strengthen their poor and sick." Babette's "quiet countenance and her steady, deep glance" have "magnetic qualities; under her eyes things [move], noiselessly, into their proper places." She is a "conqueror" and obstinacy quails under her. Babette's presence resurrects something of the old Dean's authority; the sisters' "troubles and cares" are "conjured away" by her presence, and gradually the whole community becomes cautiously grateful for her, if not to her. They are distressed when she wins the lottery and is suddenly rich enough to return to France.

When Babette literally demands of the sisters a favor—that she be allowed to cook a French dinner and that she be allowed to pay for it with her own money—the sisters naturally refuse, as is their habit. But Babette refuses to take no for an answer:

Babette took a step forward. There was something formidable in the move, like a wave rising. . . .

Ladies! Had she ever, during twelve years, asked . . . a favor? No! And why not? Ladies, you who say your prayers every day, can you imagine what it means to a human heart to have no prayer to make? What would Babette have had to pray for? Nothing! Tonight she had a prayer to make, from the bottom of her heart.

The sisters find that despite their reservations, they cannot refuse this woman. Reassuring themselves that, "after all . . . a dinner could make no difference to a person who owned ten thousand francs," the sisters accept the offered feast and find it suddenly "coming upon them, a thing incalculable in nature and range." Babette throws herself into her project, sending for food from France, much to the sisters' alarm. One day Martine goes into the kitchen and finds a turtle, enormous and alive. She has nightmares, and anxiously warns the Brothers and Sisters, but ultimately can do nothing but "[give herself] into [her] cook's hands." For the first time, these people face something that they cannot reject, something with a mind of its own, something rising irresistibly over them like a wave.

A Kind of Love Affair

They have every reason to be afraid: Babette's feast undoes them. It is, as Lorens Loewenhielm realizes, "a kind of love affair" that marries body and soul, because both body and soul are fed. Appropriately, not only the otherworldly sect, but also the worldly Loewenhielm, by chance back in the neighborhood, sit down to this dinner. The pious who have denied their bodies and the pleasure-seeker who has denied his soul meet at the same meal. They are only shadows of what they should be; they all have barricaded hearts. They are all transformed.

It is General Loewenhielm who is actually conscious of the transformation. Because he can appreciate the physical wonder of the French dinner, he recognizes its spiritual effects; he becomes the representative of the people who have no words to describe what is happening to them.

As he sets out for Babette's feast, General Loewenhielm has his heart set on one thing: still ashamed of the fool he made of himself in the Dean's home so many years ago, he is determined to impress this time, to justify himself. Expecting to be superior and condescending, he takes a suspicious first sip of his wine; he is astounded. "'This is very strange!'" he thinks; "'Amontillado! And the finest Amontillado that I have ever tasted. . . . This is exceedingly strange. . . . For surely I am eating turtle-soup—and what turtle-soup!' He [is] seized by a queer kind of panic and emptie[s] his glass."

Meanwhile, everyone else around the table, vowed to senselessness, is eating and drinking the lavish food and drink as if they eat and drink it every day of their lives. The General wonders if he is going insane, and he empties his glass over and over because "it is better to be drunk than mad." Eating as well in the home of Puritans as he would at a restaurant in Paris, he is stricken by a childlike—and very undignified—wonder.

As the General gapes at his food, everyone around him is busy not tasting it and not being astonished by it; but something is nonetheless happening to them as well. Although as a rule Berlevaag people do not speak while eating, "somehow this evening tongues [are] loosened." They tell fond stories about the Dean and the miracles he performed. They drink what they all assume is lemonade because it "sparkle[s]," and it "[agrees] with their exalted state of mind," "lift[ing] them off the ground, into a higher and purer sphere." They "[grow] lighter in weight and lighter of heart the more they [eat] and [drink]."

And they are pleased with themselves. They feel that they "no longer [need] to remind themselves of their vow" not to taste, because "it [is] . . . when man has not only altogether forgotten but has firmly renounced all ideas of food and drink that he eats and drinks in the right spirit." Completely misinterpreting what is happening to them, they nonetheless capitulate to the power of the meal.

As the night and the food go on, relationships are restored. People who slandered and wronged each other make amends with laughter. Lovers estranged by guilt come together again. "Long after midnight the windows of the house [shine] like gold, and golden song flow[s] out into the winter air." The old Brothers and Sisters go outside and stumble around in the snow holding hands. General Loewenhielm once again walks to the door with Martine and tells her the opposite of what he told her when he left before: "I shall be with you every day that is left to me," he says. "Every evening I shall sit down, if not in the flesh, which means nothing, in spirit, which is all, to dine with you, just like tonight. For tonight I have learned, dear sister, that in this world anything is possible."

In the middle of the dinner, the General, gently intoxicated by "the noblest wine in the world," does indeed get up and dominate the conversation. But rather than avoiding humiliation, he steps right into it. What he says is so new and so astonishing even to himself, that he stutters over his words; he feels that he is not consciously forming his speech, but is "a mouthpiece for a message which mean[s] to be brought forth." His speech, an exposition on grace, simultaneously encapsulates and accomplishes the miracle of Babette's feast:

Man, my friends . . . is frail and foolish. We have all of us been told that grace is to be found in the universe. But in our human foolishness and short-sightedness we imagine divine grace to be finite. For this reason we tremble. . . . We tremble before making our choice in life, and after having made it again tremble in fear of having chosen wrong. But the moment comes when our eyes are opened, and we see and realize that grace is infinite. Grace, my friends, demands nothing from us but that we shall await it with confidence and acknowledge it in gratitude. . . . See! That which we have chosen is given us, and that which we have refused is, also and at the same time, granted us. Ay, that which we have rejected is poured upon us abundantly. For mercy and truth have met together, and righteousness and bliss have kissed one another!

The General with his words is imaging and embodying his words. Thirty years ago, he rejected Martine, rejected the "vision" of purity and humility that he saw in her house; he pursued instead soul-deadening pride. At the end of his life, he is given back the opportunity that he refused: the opportunity to make a fool of himself at the Dean's table and save his soul. This time he receives it.

The Dean's sect has put up all sorts of wary walls against Babette's gift and every gift like it. But the gift bypasses those walls, and that which they have rejected is poured upon them abundantly. Babette's dinner is inescapable; it transforms the Brothers and Sisters in spite of themselves: the aged into children, enemies into friends, the severe into the joyful. They have seen heaven on earth—on the earth they despised. They are saved by the food they refused to taste. Finally the Dean's prophecy is taking place: in Babette's love affair of a dinner, body and soul, earth and heaven, kiss each other.

It is Fate

Spanning thirty years, intertwining several narratives, and interlocking those narratives in one evening, "Babette's Feast" explores the relationship of grace and time. A favorite saying of the Dean concerning the mysterious nature of God's providence recurs several times in the story. When he grants Papin permission to teach Philippa, the Dean explains his rationale: "God's paths run across the sea and the snowy mountains, where man's eye sees no track." When Philippa tells him that she no longer wants the lessons, he adds gently, "And God's paths run across the rivers, my child."

Years later, confronted by the daunting task of bringing peace to their community, Martine and Philippa reassure each other with their father's words: "God's paths [are] running even across the salt sea, and the snow-clad mountains, where man's eye sees no track." By appealing to a divine will, they are trying to give an explanation as well as a justification for the strangeness and sadness of their lives, even the strangeness and sadness they have inflicted upon themselves.

Later, Babette subtly echoes the Dean's words as she considers her own tragedies; when Martine and Philippa try to pity her losses, she shrugs her shoulders and says, "What will you ladies? . . . It is Fate." Babette's appeal to fate silences questions. There is a brutality to her belief absent from the childlike trust of the Dean and his daughters. But the intractable nature of Babette's "Fate" intensifies its glory when Fate proves kind.

It was Fate, it was the God of crooked paths, who made Lorens Loewenhielm stumble upon Martine in the street, who made Papin wander into the Dean's church, who made Babette the chief chef at the best restaurant in Paris. It was Fate, the God of crooked paths, who hardened Lorens's heart, who let Philippa fear, who had Babette's husband and son shot. It was Fate, it was the God of crooked paths, who drew them all along the paths of their losses to be the means of each other's restoration. Even the ignorant Brothers and Sisters of the Dean's sect receive this epiphany of the fundamental graciousness of reality:

They realized that the infinite grace of which General Loewenhielm had spoken had been allotted to them, and they did not even wonder at the fact, for it had been but the fulfillment of an ever-present hope. The vain illusions of this earth had dissolved before their eyes like smoke, and they had seen the universe as it really is. They had been given one hour of the millennium.

On the night of Babette's feast, the illusions of failure and despair fall away; the feasters are enabled to forgive and be forgiven because they have seen the world for the first time "as it really is": a place where destiny itself is gracious.

One Long Cry

And yet: destiny does not seem to treat everyone with equal kindness. The story of "Babette's Feast" is told so delicately that it is easy to miss the razor edge of irony. The "greatest culinary genius of the age," the woman whose dinners are love affairs, lives out the rest of her days among Puritans. She cooks her last great meal for a dozen old people who cannot taste the food. It is an irony that Babette herself is acutely aware of: she mourns to the two sisters that her old customers in France, even and especially her aristocratic enemies, had been dear to her, had "belonged" to her, because she "could make them perfectly happy"; they had been trained to appreciate her artistry and to receive it with gratitude. Even at the end of the story, their hearts softened like candle wax, the Brothers and Sisters of the Dean's sect can do no such thing; they do not credit the food Babette cooked for anything that happened to them that night. And so the climax of "Babette's Feast" must be Babette's artistic justification, Babette's own reconciliation with Fate.

After the feast, Martine and Philippa go into the kitchen and find Babette white and exhausted. They tell her that the dinner was "quite nice," even though neither of them can recollect what they ate, and they reassure her that they will all remember this dinner after she goes back to Paris. Babette informs them sternly that she will not be going back to Paris: all ten thousand francs were spent on the French dinner they cannot remember eating.

Martine is horrified; but Philippa, deeply moved, sees Babette's gift as a splendid act of self-sacrifice. "You ought not to have given away all you had for our sake," she says. Babette gives her a "strange glance," with "pity, even scorn, at the bottom of it," and answers, "For your sake? . . . No. For my own." When they wonder at her, Babette tells the sisters something that Achille Papin once told her: "It is a terrible and unbearable thing to an artist . . . to be encouraged to do, to be applauded for doing, his second best. . . . Through all the world there goes one long cry from the heart of the artist: Give me leave to do my utmost!"

Every true artist's true project, Babette declares, is a self-gift, a gift of everything. But the tragedy of art is that this kind of gift is too great to receive. No one is sufficient for it. How can you receive someone pouring themselves out on the ground in front of you? The tragic nature of this world is that it is a world in which art is spent for people who overlook, ignore, refuse it.

This Is Not the End

It was Achille Papin who sent Babette to the two sisters, twelve years before. He sent her with a reference letter that was really a farewell letter to Philippa. "What is fame? What is glory?" he wrote to Philippa out of his decline; "The grave awaits us all." But he concluded the letter with a sudden volley of hope:

And yet. . . . As I write this I feel that the grave is not the end. In Paradise I shall hear your voice again. There you will sing, without fears or scruples, as God meant you to sing. There you will be the great artist that God meant you to be. Ah! How you will enchant the angels.

Then he added, as if as an afterthought, "Babette can cook."

In a sense, "Babette's Feast" is a story about artistic failure. The old Dean made an art out of saving souls; after his death, the community he formed crumbles. Achille Papin knew that he was only capable of real art in duet—in communion; Philippa's rejection cripples him. Finally, Babette's last great artistic gesture—the feast that impoverishes her, finishes her—goes unappreciated and misunderstood.

But in response to Babette's terrible challenge, the tragic cry of the artist, Philippa speaks; her words to Babette are the justification of all the frustrated artists in the story, as well as the moment of Philippa's own artistic redemption. When Babette gives her lonely cry, Philippa takes Babette in her arms. Weeping and trembling, she blesses Babette with these words: "I feel, Babette, that this is not the end. In Paradise you will be the great artist that God meant you to be! . . . Ah, how you will enchant the angels."

Twelve years before, Achille Papin had blessed Philippa with these very words. As she speaks them, Philippa makes them her own. She receives Papin's blessing and in her turn bestows it. Her words acknowledge the tragedy: she admits her own and her community's insufficiency to receive what Babette has to offer. But she proclaims that in the end it does not matter, because it is not the end. Babette's feast was a foretaste of the final and eternal return of stubborn grace; in Paradise everyone will give and receive perfectly. With this promise, Philippa herself becomes a foretaste of Babette's satisfaction.

Babette's feast was orchestrated by Achille Papin. He knew exactly what he was doing when he sent Babette to Berlevaag. He knew that Babette was a greater artist than he, and that she could accomplish the project he had been unable to accomplish: turning Philippa into an artist. The feast was his work of art and love as well as Babette's; and with her words, Philippa consummates it, declares its success, and allows both Papin and Babette to have done their utmost on her.

In this act of gratitude, Philippa becomes an artist herself, because she brings Papin's story to a good and lovely close. Her recognition of grace justifies his truncated life, the life she herself truncated. And in this she, too, is an artist, a grace-giver, a designer of lives. They become a kind of trinity, these three artists: Achille sends Babette as a gift to the community; Babette gives herself to the utmost; Philippa responds in gratitude, which is itself a gift.

Gracious Art, Artistic Grace

Dinesen's feast of a story is a celebration of food and wine, tragedy and comedy, personalities rich and ridiculous. It is also, I believe, theologically profound. This little story preaches two startling things about the nature of this world and the God of this world—two things that should, perhaps, not startle us, but that we need regularly to be startled by.

Grace does not need our permission to go to work on us. In God's economy, grace is stubborn, relentless, and inescapable: it hounds; it gets inside without permission; it rises like a wave. Our stories are written to double back and catch us unawares, to drive us again to the moments of our failure and force us to receive what we once refused.

But the reason that art can be gracious is that Grace is an artist. In our little worlds of perfect justice, we assume that our failures will frustrate God's purposes and disqualify us from joy. We therefore live as if guilt and regret are righteous, fear holy, despair a wise conclusion to draw from the mess we have made. But God has far too much at stake in us for that to be true. Grace is like Achille Papin, refusing to abandon Philippa to a life of artistic barrenness because his own life, his own art, would be meaningless if he did not complete his work in her. Grace is Babette, the culinary genius of her age, spending all her money and skill on people who cannot taste, because it is her one opportunity to do her utmost. The reason God loves us faithfully is not because we have some inherent worth or usefulness that we increase by our cooperation, undermine by our failure. It is because God is an Artist, and making something from nothing—doing his utmost—is his great desire, the one long cry of his heart.

But he is not content with that—and neither, miracle of miracles, are we. An artist has not done his utmost until he has, like Lorens Loewenhielm, given taste to the tasteless, until he has, like Achille Papin, created in duet—and God is such an artist. He will not be content until he has made us into artists, too. At our best, at our truest, we desire to justify his gift, to respond with the gratitude that is itself an artistic act.

For now, his and our project is often shockingly anti-climactic: anecdotal failures and even more anecdotal redemptions, a meal no one can taste, dying people playing in the snow. But one day—how it will enchant the angels. •

Leta Sundet is a Ph.D. student in literature at the University of Dallas and attends a Reformed Episcopal church. Her current literary interests include Shakespeare, Jane Austen, and children's books.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor