View

Our Christmas Home

William E. Graddy on the Deepest Longings of the Restless & the Lonely

It seems that every other store or coffee shop I visited three years ago this December was playing either "Rockin' Around the Christmas Tree" or "I'll Be Home for Christmas." The sock-hoppish cheerfulness of the one was even more glaringly out of key with our national mood that winter than the twilight wistfulness of the other, but the continuing popularity of "I'll Be Home" remains the greater puzzle to me nonetheless. After all, the power of this slow, quiet song lies mostly in the historical moment it captures—the weariness, the dislocation, and perhaps especially the bittersweet hope-against-hope that millions of Americans felt in 1943, when it was released. And awareness of the past, certainly any vital sense of connection with it, has shrunk to the vanishing point in our collective psyche.

At least as strikingly absent is the bond, echoed poignantly in Bing Crosby's song, between the state and the individual, particularly between the civilian and the soldier, that held strong in our grandparents' era. Rosie the Riveter's body may have been stateside, but her heart was in the Pacific, or Europe, or Africa with the troops. Fred or Eddie the GI may have just dodged shrapnel bursts or fought past exhaustion in Anzio, but give either a minute and a scrap of paper, and he'd be writing the folks back home in Ohio. In the waning months of 2012, though, we listened to the same rich but sad voice intone "I'll Be Home" scores of times over in Starbucks or Target, but we sipped our lattes and stroked our smartphones without a flicker of recognition that (a) we were hearing a song about war, and (b) we as a nation were at war—our longest war yet—right then.

The explanations for that profound disconnect are complex, but the two I'd like to posit here, our relentless mobility and its corollary, our radical identification of identity with separateness, resonate in surprising ways with the facts of Jesus' birth, facts that we've grown adept at listening past and are used to hearing spoken in inappropriately smooth voices. For the world our Lord entered over two millennia ago was in important ways as restless, disjointed, and lonely as the world our twenty- and thirty-somethings inhabit now. Recognizing this may help us see, in turn, the depth of Jesus' identification with that world, and, out of this, an authentic hope may spring.

Strangely Nested Journeys

People move, they become travelers, when their mission or their need lies somewhere other than where they are; and, taken together, Matthew's and Luke's nativity accounts give us a strangely nested set of journey narratives: An old priest, Zechariah, stumbles from Jerusalem back to his aged wife, Elizabeth, and to a house that, after decades of childlessness, will in less than a year welcome a baby son. A young and also miraculously pregnant woman, Mary, hurries from Nazareth to Elizabeth's hill-town residence in Judea, where she lodges for three months before returning home. A troubled but obedient carpenter, Joseph, travels as tenderly as poor people could from Nazareth to Bethlehem with Mary, to whom he is now betrothed and whose time of delivery has drawn near. Prompted by angels, ill-smelling and probably illiterate shepherds trudge, empty-handed and curious, from nearby fields toward the manger where Mary's baby lies. Alerted by observation and study, learned astrologers bearing perfume and gold finish their lengthy trek to Bethlehem from the Persian East.

Jew and gentile, pagan and pious, young and old, woman and man, privileged and peasant—no one in this dichotomous cast gets to stay home long, or to return to the world each had formerly taken for granted. No sooner do Mary and Joseph hear the very elderly Simeon and Anna testify that their new Baby will save Israel than they themselves have to flee Israel to save their new Baby, becoming refugees in Egypt to escape Herod's murderous jealousy and fear.

But heaven's Christmas journeys trump all those put together. In both revelation and the popular imagination, angels have wings, so Gabriel's two trips to Palestine and the heavenly host's group flight to Bethlehem may not have been arduous. For God's Son Jesus, though, it was a very different story. His journey would be from a prince's throne to a peasant's crib to a criminal's cross, and only after lying dead three days in a donated tomb would he reenter life, having made provision for the rest of us to live rather than die, and to make our own final journeys into his eternal presence.

The Vast Distance & Its Bridge

In the end, God's journey had to be radical and lonely beyond imagination ("Could you not watch with me one hour?" "My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?") because our separation is extreme. Our distance from him, from our best selves, and from each other is vast, and is bridgeable only by Christ's endurance of and triumph over the cross.

Such whisperings may come in the night's quietest or darkest hours, but pride rejects and independence revises them, and we content ourselves with resolutions to be or to do better. So we give our communities hopeful names like "Newtown," and plant excellent homes and schools in them, only to realize that Herod's two-millennia-old Massacre of the Innocents, not to mention countless other slaughters we've denied or forgotten, has been re-enacted yet again.

Shadowed by Calvary alone, the hope of Christmas would be fatuous—an antique Pixar fantasy for the toddlers, Mammon decked out in a white beard and red plush outfit for the rest of us. If God's alphabet of grace ended with Gethsemane and Golgotha, faith would be mute as well as impotent, silenced by a roll call of names we want desperately to forget: Armageddon, Auschwitz, Crimea, the Ku Klux Klan, Pol Pot, Sandy Hook. . . . But God is Omega as well as Alpha, and Calvary in fact stands flanked by two lights that darkness simply can't extinguish: the newly occupied manger and the recently vacated tomb.

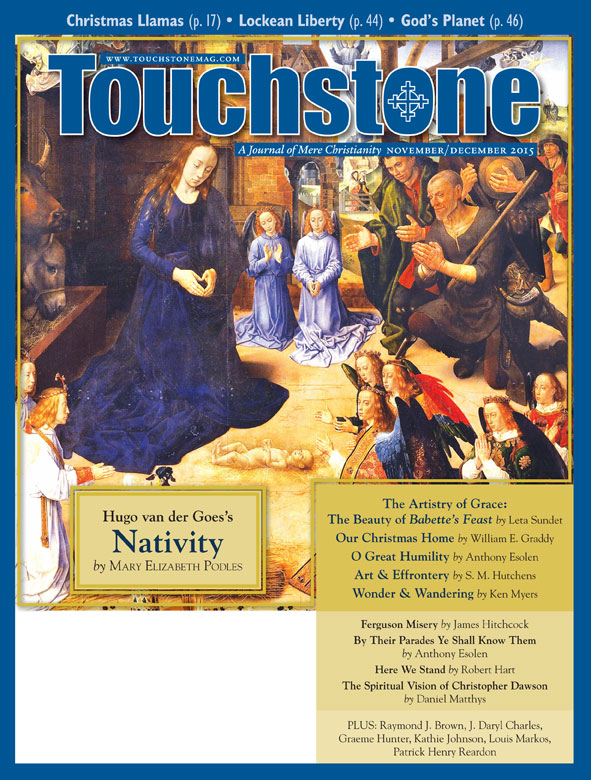

This indeed is the truth we and all generations of Christians are commanded to proclaim. Instead of making this gospel known, though, we have succeeded all too often in making it familiar. In our re-scripting, the Holy Family become travelers, not refugees, and we quickly settle them into a landscape more suggestive of a Thomas Kinkade painting than of a rocky village in a Roman-occupied land. Domesticity supplants dislocation, strangeness, and tension, so that Mary emerges as a model mother, largely spared the excruciating pain of a sword-pierced soul (Luke 2:34–35). Indeed, we plane all the rough places in the narrative, morphing Christ into a dispenser of forgiveness and reassigning all his urgent calls for repentance and warnings of judgment to his cousin John, making the Baptizer more foil than

forerunner.

Linked by Muted Melancholy

Meanwhile, the numbers of the "Nones" in America and the rest of the developed world grow. Increasingly, their connections with us and with each other are electronic. We know them mainly by their possessions and their obsessions, but they in fact spend most of their waking hours at jobs that pay less even as they grow daily more insecure and demanding. Unceasingly mobile, they view relationships as temporary, certainly as nonbinding, and they value associations in utilitarian terms.

Although self-centered, these folks are not markedly selfish. Their interests are in fact more likely to be global than were their predecessors'; and, except for their disdain of the traditional, they are quite uncynical. After all, they never really hoped in the first place. Maybe this is why they find some instinctive link with the muted melancholy of "I'll Be Home for Christmas." For the last words of that song simply make explicit what the resigned sadness of its music was expressing all along: "I'll be home . . . if only in my dreams."

The "Nones," are, in short, too well acquainted with the night to believe in our revised, artificially lighted versions of the Christmas story, and of the gospel generally. The dislocations, the pain, the puzzlements, and perhaps even the demands of the original reflect experiences far closer to their own, as they sit, like A. E. Housman's speaker, "stranger[s] and afraid, / In a world [they] never made." •

William Graddy taught literature and writing at Trinity College, Deerfield, Illinois, for 38 years. His work has appeared previously in Touchstone, several other journals, and the Eerdmans’ Handbook to American Church History.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christmas from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor