Feature

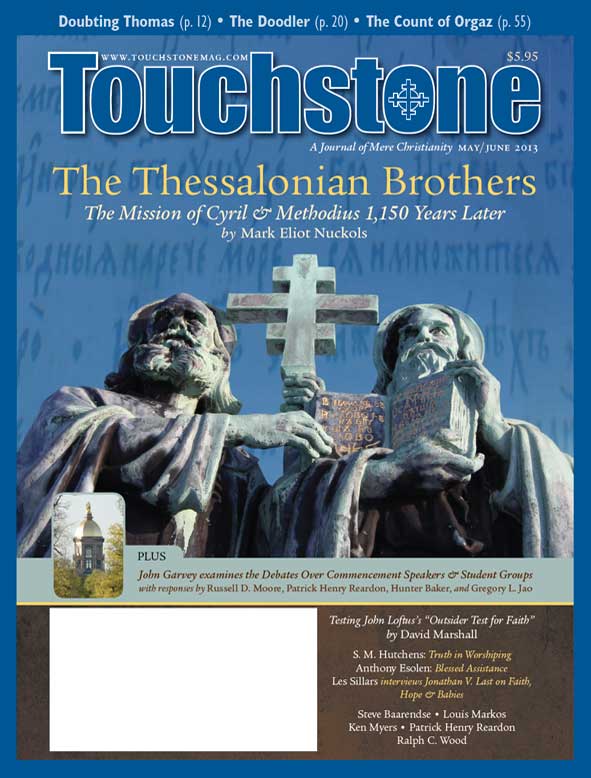

The Thessalonian Brothers

The Legacy of the Mission of Cyril & Methodius 1,150 Years Later

While Paul began his evangelization of Europe in Philippi, the most successful congregation he founded in Europe may have been in Thessalonica. The church there has a rich legacy, perhaps most greatly exemplified in two brothers, Cyril and Methodius.

The Christians of Thessalonica, 800 years after Paul, sent these two on a mission to Eastern Europe. They prayerfully and obediently abandoned their chosen paths in life and answered God's call to become missionaries to the Slavs. Their endeavors laid the cultural foundations that would enrich the lives of hundreds of millions.

The year 2013 marks the 1,150th anniversary of that mission of 863, the "Moravian Mission." The legacy of Sts. Cyril and Methodius remains strong, especially in Central and Eastern Europe. In brief, they created an alphabet and codified the first Slavic literary language, giving rise to Slavic liturgical and literary traditions, as well as a sense of Christian devotion and identity that is both distinctively Slavic and thoroughly connected with European civilization as a whole.

Named co-patrons of Europe by John Paul II in 1980, Cyril and Methodius served as an inspiration for the faithful behind the Iron Curtain. Recognized as saints by both Eastern and Western Christians, they have also inspired efforts toward Christian unity.

Historical Perspective

Prior to their mission, much of Europe was still pagan, especially in the north. The Carolingian dynasty, established by Charlemagne six decades earlier, had been divided among his descendants. The Byzantine Empire had come under increasing attack from Arabs, Persians, and even Russians, and would soon face challenges from Bulgaria. Much of the continent lived under tribal rule and was subject to invasions from less-settled peoples.

The Slavs, an Indo-European people on the move since the fifth century, could be found from the Elbe to the Balkans and east to the Volga. After 804, a number of Slavic tribes became firmly established in the central Danube region.

The most significant of the nascent Slavic states was Great Moravia, which at its height probably covered most of present-day Moravia and Bohemia (the Czech Republic) and Slovakia, and some neighboring areas in today's Hungary and Austria. In the politics of shifting alliances, conquest, and rebellion, Moravia became a vassal state of Louis the German's Kingdom of the East Franks, the eastern portion of the Carolingian Empire. Under the auspices of Frankish monks, missionary activity had already begun in this territory.

By the mid-ninth century, missions from northern Italy, Bavaria, and the diocese of Salzburg had preached the gospel in these Slavic lands, although the depth and breadth of conversions are disputable. The Moravian prince Rostislav sought missionaries to educate his people further in the faith. As recorded in the Vita Constantini (unless otherwise noted, all quotes from the Vita Constantini and the Vita Methodii are taken from Medieval Slavic Lives, Marvin Kantor, ed., Slavic Publications, 1983), Rostislav wrote to the Byzantine emperor Michael III:

Though our people have rejected paganism and observe Christian law, we do not have a teacher who can explain to us in our language the true Christian faith, so that other countries which look to us might emulate us. Therefore, O lord, send us such a bishop and teacher; for from you good law issues to all countries.

Both Michael and Photius, patriarch of Constantinople, understood the expedience of converting the Slavs: in 860, Russians had attacked Byzantium from the north. Rostislav, too, may have had political motives—a Byzantine mission might establish some measure of independence from the Franks. But he also seems to have been interested in sincere conversions, given his insistence on the linguistic qualifications.

Biographies

The men who met those qualifications were two brothers from the Balkans. Constantine (who took the monastic name Cyril only at the end of his life) and Methodius were born in Thessalonica and likely raised as Greek–Slavic bilinguals. There were a substantial number of Slavs in that city at the time; their mother, Maria, may have been one. Their father, Leo, was a man of considerable wealth and, according to the Vita Constantini, a drungarios, a high-ranking military officer.

Constantine, the youngest of seven, exceeded the others in talent. "When [his parents] sent him for instruction," the Vita Constantini tells us, "he surpassed all his fellow students in learning, as his memory was very keen. He was then a marvel." He was soon sent to Constantinople for a thoroughly Hellenic education, partly acquired under the tutelage of Photius, who later became patriarch of Constantinople.

Constantine declined marriage to a woman of high standing and sought a different path. He was made librarian to the patriarch but soon thereafter hid in a monastery. When he was found, he was persuaded to accept a chair in philosophy at the university in Constantinople. Henceforth, he was known as "the Philosopher."

On a mission to the Abbasid Caliphate, according to the Vita Constantini, he defended the doctrine of the Holy Trinity. Later, accompanied by his brother Methodius, he journeyed to the Khazar Khaganate, north of the Black Sea. To the astonishment of his debaters, he fielded questions on the Law and prophecy with ease, quoting the Old Testament knowledgeably and forcefully, but he still failed to convert the Khazars from Judaism. While in the Crimea, he found what he believed to be the relics of St. Clement, which would play an important role later in his life.

But the mission to Moravia would be the defining event of his and Methodius's life. Methodius had ruled a Slavic province for some years before taking the monastic habit, and Constantine, now in frail health, had turned from his prestigious academic work to pursue the contemplative life. But both brothers left their stations, which they had earlier accepted as the divine will, in order to answer God's call. Like other missionaries throughout Christian history, they departed a highly developed society for cultural backwaters.

The Moravian Mission

It was probably Photius, Constantine's former teacher, who selected him for the mission, although the Vita Methodii tells us that Emperor Michael did so, instructing him to take his brother: "For you are both Thessalonians and all Thessalonians speak pure Slavic." "Slavic" is appropriate in this context, as the dialects spoken by various tribes were mutually comprehensible, and there was no written standard prior to Cyril's work.

For his translation of Scripture and of liturgical books, a script had to be invented, as had been done before for nationalities such as the Armenians. Most Slavic philologists believe that the alphabet devised by Cyril was Glagolitic, and that the Cyrillic named for him was developed later by his disciples, as it is clearly based on the Greek alphabet. Glagolitic is, to the modern Western eye, "exotic," consisting of various combinations of triangles, circles, arcs, and straight lines. It bears little resemblance to other alphabets, but there are some similarities, e.g., the letter Ш (also used in Cyrillic), which represents the sh sound and is taken from the Hebrew character "shin" (). Unlike some of history's crude attempts to adapt ill-suited alphabets to foreign tongues, Cyril's Glagolitic was, according to the scholar Marvin Kantor, "an entirely new invention and showed his keen ability to distinguish and represent the phonological structure of the Slavic language very precisely."

Constantine standardized the Bulgarian–Macedonian dialect of the Thessalonian region, adapting it to more sophisticated Byzantine Greek syntax and word-formation patterns for the purpose of expressing religious and legal concepts. As Kantor comments:

He was not only a faithful translator of the Gospels, but a literary artist, and the language (which came to be known as OCS [Old Church Slavonic]) of his translations was poetic and at times more vivid and plastic than the neutral Greek original. What an incredibly powerful effect it must have had on the Slavs of Moravia when from the East these two missionaries came to them bearing books written in Slavic, and in such an impressive style!

It is perhaps no coincidence that this, the only Byzantine-sponsored mission to link literacy so strongly with the new faith, also produced what was probably the most successful conversion in that empire's lengthy history.

The brothers first arrived in Pannonia (comprising today's western Hungary and possibly eastern Austria). The Slavic duke Kocel received them warmly, according to one version of the Vita Constantini (quoted here from Alexander Schenker's Dawn of Slavic, Yale University Press, 1995), and "taking a great liking to the Slavic letters, learned them himself and supplied some fifty students to study them."

After a productive seven-month stay there, however, Constantine and Methodius moved on to Moravia proper, where they became embroiled in the growing rivalry between the Franks and the Slavic princes. The Bavarian clergy jealously guarded their jurisdiction, which was growing eastward along with Frankish territorial expansion, and they eyed the introduction of the new Slavic liturgy as an encroachment. Pope Nicholas I summoned the brothers to Rome to answer charges leveled at them by the Bavarian church authorities.

The Death of Cyril

The two brothers departed for Rome in 867. On the way, they stopped in Venice to debate Western clerics who insisted on the tradition of using only Hebrew, Greek, and Latin for worship, which the Slavonic sources deride as the "trilingual heresy" or "Pilatian heresy" (after Pilate's use of those three languages for the sign on Christ's cross). Constantine is said to have responded with St. Paul's words: "that every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord" (Phil. 2:11).

By the time they arrived in Rome, Pope Nicholas had died and been replaced by Hadrian II, who was both more favorable to their cause and more conciliatory towards the East. At about the same time, the new emperor in Constantinople removed their patron Photius as patriarch, weakening their ties to Byzantium. From this point forward, they focused their efforts on relations with Rome.

When they arrived bearing the relics of St. Clement, the new pontiff welcomed them and blessed their Slavic Scriptures. Their disciples (mostly from Moravia and Pannonia) were ordained, and a number of Slavic liturgies were celebrated there.

Constantine soon took monastic vows and the name Cyril, dying in Rome on February 14, 869. Methodius implored the pope to allow him to take Cyril's remains back to Byzantium, in accordance with their mother's wishes. Hadrian at first concurred, but at the entreaty of the Roman bishops, decided to have him interred in Rome. Seeing Hadrian's determination, Methodius offered as a compromise that Cyril be buried in the Basilica of St. Clement, to which the relics had been translated shortly before. Cyril's tomb and shrine are still found there.

Methodius in Moravia

Hadrian next sent Methodius back to Pannonia as archbishop of Sirmium, an ancient ecclesiastical province under the direct jurisdiction of the Holy See. This move, meant to keep Bavarian clergy at bay, only provoked their indignation; they claimed privileges in the region granted under Charlemagne.

In 870, the East Franks deposed the Moravian Prince Rostislav, blinding and imprisoning him and replacing him with his treacherous nephew Svatopluk. Methodius, left at the mercy of the Germanic authorities, was imprisoned for three years in Swabia. The newly elected Pope John VIII upbraided the Bavarian clergy for their actions. In a letter to Bishop Hermanrich of Passau, he wrote (quoted from Schenker):

Would the cruelty of any layman, not to say a bishop, indeed of any tyrant, exceed your temerity? Would [it] go beyond your bestial ferocity when you imprisoned our brother and fellow bishop Methodius, tortured him for a long time in open air in sharpest cold and frightful rains, removed him from the affairs of the church which were entrusted to him, and went so far in your frenzy that you would have struck him with a horsewhip . . . had you not been prevented by others?

After threats of excommunication and other consequences, the Bavarians released Methodius and allowed him to resume his work in Moravia in 874. Pope John forbade him to celebrate the Slavic liturgy, but allowed sermons in the vernacular. In 880, Methodius journeyed to Rome and secured his appointment as archbishop of Pannonia and convinced the pontiff to allow services in Slavic.

Despite political intrigues and ecclesial controversies, Methodius remained in Moravia, where he translated Scripture, completing everything except the books of the Maccabees, according to the Vita Methodii. Other sources claim he baptized the Bohemian duke Boˇrivoj, founder of the Pˇremyslid dynasty and grandfather of Wenceslas (Václav), the patron saint of the Czechs, known to English-speakers through the Christmas carol. According to Western sources, Methodius died in 885 in Velehrad, modern-day Moravia's most prominent Catholic pilgrimage site, although Eastern tradition places his burial in today's Uherské Hradištˇe.

Shortly after his death, the increasingly powerful Frankish rulers and Bavarian clergy expelled his disciples from Moravia, and the Latin rite prevailed, as Pope Stephen V forbade the Slavic liturgy. Within twenty years, a combination of Franks and Hungarians reduced the Moravian state to tatters. It must have seemed that the strivings of the brothers from Thessalonica had been in vain.

The Legacy

To this day, the Slavs who practice Western Christianity use Latin letters (with diacritics), while Orthodox (and Greek-Catholic) Slavs write in Cyrillic. This fact is due largely to the history just related.

While Cyrillic became standard writing in Slavia Orthodoxa, some Church Slavonic survived in the lands of Slavia Catholica. Even after the expulsion of the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, the Slavonic rite survived in small pockets of Bohemia, and possibly in today's Slovakia and southern Poland. The Sázava monastery of Bohemia continued its use (or revived it after some interruption) until the eleventh century. The Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV, holding court in Prague, obtained papal permission for a Glagolitic rite in 1347, but it only lasted until the monastery he founded was destroyed during the Hussite wars early in the following century. Charles renewed the Slavonic liturgy by inviting Benedictine monks from Croatia, which has maintained a Glagolitic tradition to this day, especially in the monasteries of the Dalmatian coasts and islands. Western visitors to Zagreb's Cathedral of St. Mark, for instance, will find a 1941 engraving in the wall using the exotic letters.

For the continued Church Slavic tradition in the East, we can largely thank the disciples of Cyril and Methodius, who, according to the Life of Clement of Ohrid, escaped down the Danube on a raft to the Bulgarian Empire, which had recently adopted Eastern Christianity. Foremost among them is St. Constantine of Preslav, who founded the Preslav Literary School. Here, he and another Cyrillo-Methodian disciple, Naum, developed the Cyrillic script. The school grew into a center of translation and artistic endeavors, and within a century there were scriptoria in much of Bulgaria. Another disciple, Clement, taught some 3,500 disciples at Preslav before founding a monastery at Ohrid, which became another prolific literary school. Clement of Ohrid is the patron saint of the modern-day (and former Yugoslav) Republic of Macedonia.

Serbia would also become an integral part of the Byzantine Commonwealth, particularly with the consecration of St. Sava as the first archbishop of the autocephalous Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian monks performed an invaluable service to the Cyrillo-Methodian tradition, copying and preserving manuscripts and translating Byzantine texts, most famously at the Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos. The Hilandar tradition has been expanded and preserved by the microfilming of its manuscripts (and those of several other Athos monasteries), now held in The Ohio State University's Hilandar Research Library. With several thousand documents, this library is the largest repository of Cyrillic manuscripts on microfilm in the world.

And then, of course, there is Russia. Prince Vladimir of Kiev was baptized in 988, famously requiring the baptism of his subjects and the destruction of idols of the old pagan Slavic gods. By the middle of the following century, the polity of Kievan Rus' was raised to metropolitan status. It was most likely Bulgarian monks and clergy who first brought Slavonic letters to these eastern Slavs. As the Ottoman Turks penetrated deeply into Balkan Slavic territory in the following centuries, more monks began taking refuge in Russian lands. After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, Muscovy became a leading center of the Orthodox world.

Through the later influence of the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, the Cyrillic alphabet was adapted to various non-Slavic languages, including Turkic and Uralic languages, especially in the former Soviet Union and Mongolia. Although Romanian is a Latinate language, not Slavic, Cyrillic remained an official alphabet in Romania until the mid-nineteenth century, and significant Slavonic elements are still often used in the traditional Romanian Orthodox liturgy. Today, some quarter-billion people use the Cyrillic script. Cyrillic, along with Chinese and Arabic characters, is rapidly claiming its turf on an internet once hostile to non-Latin writing.

Modern-Day Echoes

While neither Cyril nor Methodius sought fame, they earned their honors posthumously. Numerous churches, orders, and institutes, in both Europe and the United States, bear their names. Danville, Pennsylvania, for instance, is home to the Basilica and to the Sisters of Sts. Cyril and Methodius. Their feasts are national holidays in several countries: May 24 in Bulgaria, Macedonia, and Russia, and July 5 in the Czech Republic and Slovakia (although their saints' day is February 14 in the General Roman Calendar). In socialist countries, it was no coincidence that the date on which the Church had commemorated Cyril and Methodius became National Education Day.

In 1980, Blessed John Paul II, who often prayed for the Slavic countries at Cyril's tomb in the Basilica of St. Clement, declared Cyril and Methodius co-patrons of Europe (a distinction they share with St. Benedict). John Paul further extolled them in his 1985 encyclical Slavorum Apostoli (Apostles to the Slavs). One can easily imagine the symbolic significance of the brothers from Thessalonica for the Polish pontiff, who spoke of the need for divided, Cold-War Europe to "breath with both lungs." Towards the end of that encyclical, he wrote:

[G]rant to the whole of Europe, O Most Holy Trinity, that through the intercession of the two holy Brothers it may feel ever more strongly the need for religious and Christian unity and for a brotherly communion of all its peoples.

While he was able to make several pilgrimages to his homeland, John Paul II never received permission to enter communist Czechoslovakia, not even for the 1,100th anniversary of Methodius's death at Velehrad in July 1985.

That event turned into a fiasco for the regime, which tried through various obstructions to limit the number of participants. Authorities were shocked when an estimated 150 to 200 thousand of the faithful, many of them young people, turned up for the "national pilgrimage." When the minister of culture tried to co-opt the event, calling it a "peace demonstration," the crowds responded with whistling (the equivalent of booing) and chants demanding religious freedom and permission for a papal visit. John Paul finally made his first Velehrad pilgrimage in April 1990, shortly after the fall of communism.

Gospel Heritage

Dozens of events have been scheduled to mark the 1,150th anniversary of the brothers' mission. Preparations in the Czech Republic and Slovakia began in 2011. Relics of St. Cyril, a gift from the Vatican to the diocese of Nitra from the time of the Second Vatican Council, have traveled to every diocese in Slovakia, making stops in numerous parishes. In the Czech Republic, the Orthodox and Catholic churches, as well as the Czech Academy of Sciences, are collaborating on a docudrama looking back on the undivided Christianity of the brothers' times. An international congress, "Sts. Cyril and Methodius among the Slavic Nations," took place at Rome's Pontifical Oriental Institute in February. In May, special exhibits will open in Prague and Velehrad. The patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew I, is to attend an Orthodox celebration on May 25 at Mikulˇcice, the Czech Republic's most important archeological site, which contains numerous graves and the foundations of buildings from Great Moravia.

During this anniversary year, it is worth remembering the genius of Cyril, the sufferings of Methodius, and the dedication of both to bringing the gospel of Jesus Christ to the Slavic peoples. While the creation of a new alphabet was significant, millions are indebted to the brothers from Thessalonica—and their disciples—for a heritage that goes well beyond their linguistic accomplishments. Christians of all denominations and languages can be inspired by the personal sacrifice and example of these "Apostles to the Slavs."

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor