Feature

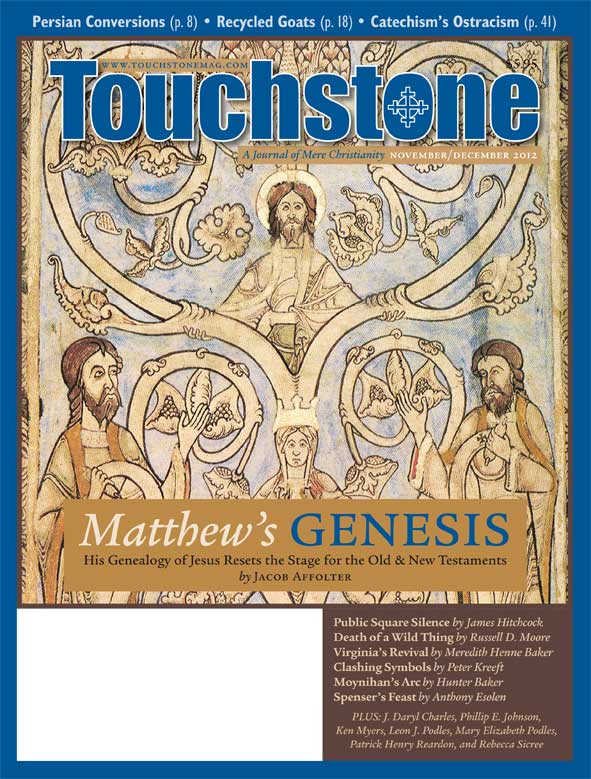

Matthew's Genesis

The Genealogy of Jesus Resets the Stage for the Old & New Testaments by Jacob Affolter

I once heard a pastor say that many people resolve to read the entire New Testament but never get past the genealogy in the Gospel according to Matthew. I am sure that many readers consider this chapter among the least accessible parts of the New Testament. They may wish that Matthew had simply stated that Jesus Christ was "the Son of David, the Son of Abraham," and then gone straight on to the Nativity story.

While I sympathize with these readers, I believe it would be a serious mistake to skim through this genealogy. It is not merely a list of names or a legal document. Nor does it simply give a bit of background to the story of Christ's Nativity. Rather, it shows us how to understand Matthew's entire Gospel—and through it all of history—in the light of Christ.

A Poetic Structure

The first thing to notice about the genealogy is that it is not just a list. Rather, it is a highly structured literary arrangement. One reason people find it tedious is that they treat it as straight prose, when they should treat it more like a poem. To see this, try reading the passage slowly and evenly, taking special care not to push through the paragraphs that frame the list. If you do this, you can see that there is a rhythmic quality to the passage. The list itself moves at a slow, formal pace, punctuated by short paragraphs that put the list of names in a larger context.

On this point, it is instructive to contrast the genealogy in Matthew's Gospel with the one in Luke. In chapter 3 of his Gospel, Luke simply gives us a matter-of-fact list of names. Literally translated, Luke says, "Joseph of Heli of Matthat of Levi of Melchi . . ." and so on (Luke 3:23–24). In contrast, Matthew says, "Abraham begot Isaac, and Isaac begot Jacob, and Jacob begot Judah and his brothers . . ." (Matt. 1:2). Matthew deliberately draws the genealogy out, for reasons I will discuss in the next section.

The second point to notice is that the genealogy is interrupted by small insertions. Matthew takes care to set up a very steady rhythm, and then, at certain points, he deliberately breaks it. He does this primarily by adding an extra detail about a particular person in the list. For example, when he writes that "Boaz begot Obed," he adds "by Ruth" (Matt. 1:5). Through these small interruptions, Matthew draws our attention to specific features of the genealogy that he wants to emphasize.

Third, after neatly wrapping itself up with a closing line about the three groups of fourteen generations, the genealogy immediately leads into a passage with a very different style. Whereas the genealogy is almost poetry, the Nativity story that follows is told in straightforward narrative prose.

I submit that these structural features are not accidental. On the contrary, they provide clues as to how we should understand both the genealogy itself and the entire Gospel according to Matthew.

The New Genesis

The first theme I would draw from the structure of the genealogy is that Matthew is presenting his Gospel as the "new Genesis." Note, for instance, that both the genealogy and the Nativity story start out with some form of the Greek word genesis: the genealogy by saying, "The book of the genealogy (geneseos) of Jesus Christ . . ." (1:1), and the Nativity story by saying, "Now the birth (genesis) of Jesus Christ was as follows . . ." (1:18). In telling us that we are reading about a beginning, these phrases immediately bring to mind the opening words of the Old Testament Book of Genesis: "In the beginning God made heaven and earth."

There is a second parallel worth noting. Some commentators, following a variant reading, have argued that there is a difference between the word translated as "genealogy" in the opening verse and the one translated as "birth" in verse 18. This difference might be important. But we should also pay attention to the similarities. By using similar terms at the opening of each passage, Matthew indicates that he is not telling us two different stories about Christ; rather, he is telling us the same story twice. Both passages are versions of the same story: the story of the beginning of Jesus Christ.

This should remind us that the first two passages of the Book of Genesis also tell the same story twice—in this case, the story of Creation. Like Matthew's Gospel, Genesis opens with a highly structured, rhythmical recitation (Gen. 1) of the Creation story, followed by a more prosaic, narrative version of the same story (Gen. 2). These structural parallels signal to us that what we are reading in Matthew is a new Genesis that is closely connected to the old Genesis.

A Key to the Old Testament

These structural points, in turn, give us a clue to one of the major themes of Matthew's Gospel: that it is a key to understanding the Old Testament. We have already noted how the first line of the Gospel tells us that we are reading "the book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ"—

a genealogy that provides us with a summary of the entire history of Israel, from Abraham to Christ. The first line of the Nativity story then tells us that we are reading about "the beginning of Jesus Christ." By establishing this parallel, Matthew is pointing to the real meaning of the Old Testament: understood properly, it is the book of the beginning of Jesus Christ.

In making this point, Matthew also makes it very clear that the New Testament does not replace the Old Testament; rather, it fulfills the Old Testament. Moreover, against later heretics like Marcion, Matthew's Gospel tells us that we still have good reason to read the Old Testament. By beginning his Gospel with a genealogy, Matthew is giving us a summary of the Old Testament in a way that presents it as a key to understanding the life of Jesus Christ. Just as the genealogy is an aid to understanding the Nativity story, so, by extension, Matthew signals to us that the entire Old Testament is an aid to understanding the significance of the life of Christ.

With this in mind, let us now look at the "interruptions" in the flow of Matthew's list of ancestors. These bumps in the rhythm of the passage draw our attention to a number of Old Testament themes that Matthew will bring into clearer focus in the Nativity story. I will focus on four of these themes.

Sinners Play a Role

The first is that God allows sinners to be part of his plan for the redemption of the world. Matthew deliberately emphasizes that God graciously included a number of sinners in the genealogy of our Lord, and even let some of their sinful actions form part of the chain of events that led to the birth of his Son.

In particular, Matthew draws our attention to Judah, Tamar, Rahab, and David. He first reminds us that the sinful actions of Judah and Tamar (Gen. 38) eventually led to the birth of David, and, through him, to Christ. He then reminds us that Boaz's mother was Rahab, a prostitute from Jericho (Josh. 2). Finally, he takes care to point out that Solomon's mother was Bathsheba. Significantly, he does not refer to her as Bathsheba, but as "the wife of Uriah," thereby reinforcing the point that David had married her after committing adultery and murder (2 Sam. 11–12).

Gentiles Are Called

A second theme is that God's plan of salvation always included a call to the Gentiles. Matthew takes care to emphasize that the Davidic kings had non-Israelite ancestors. It is instructive to note that, aside from Mary, the Theotokos, Matthew only mentions mothers who were not Israelites. Sarah is not mentioned, but Ruth, Rahab, and the wife of Uriah are. Thus, anyone who considers complete ethnic purity a requirement for service to God would have to reject David himself.

Younger Brothers Are Chosen

A third theme to note is that God does not always follow the normal human pattern of inheritance. Matthew subtly points to several occasions when there was some kind of irregularity in the normal legal pattern of inheritance, particularly noting cases in which an inheritance went to a younger son. For instance, he takes care to tell us that Judah was the father of Perez and Zerah (Matt. 1:3). We are invited to recall that Zerah stuck out his foot first, but then withdrew it, so that his twin brother was actually born first. Even prior to that, Matthew notes that Jacob begot "Judah and his brothers" (Matt. 1:2). This reminds us that Judah had three older brothers, who had lost their place in the line of inheritance due to their sins (Gen. 49:3–12).

Later, he tells us that Boaz "begot Obed by Ruth" (Matt. 1:5). This is striking for several reasons, one of which is that the Book of Ruth took care to emphasize that Boaz was to provide a child for Naomi, and by implication for Ruth's departed husband (Ruth 4:5–6,17). Yet the genealogy simply speaks of Obed as the son of Boaz and Ruth (cf. Ruth 4:21; 1 Chr. 2:12). And finally, Matthew reminds us that Solomon was not only a younger son but also the son of the woman who had been the wife of Uriah (Matt. 1:6).

By emphasizing these characters, Matthew reminds us that God was never bound to follow the normal laws of inheritance in giving his blessing. With the Lord, it was never simply a matter of passing on the privilege to the oldest biological son.

Going Beyond What's Required

The fourth theme to note is that Matthew emphasizes people who went beyond the bare requirements of the law to exercise mercy. Judah, for instance, after having sinned, recognized that he was guiltier than Tamar was, and so he refused to punish her as the laws of the time would have required. Ruth had a right to return to her family, but she refused to abandon Naomi—even when Naomi ordered her to do so (Ruth 1:6–18). Boaz was not obligated to take Ruth as his wife, but he chose to do so (Ruth 4).

And it is surely significant that Matthew does not say "Bathsheba," but "the wife of Uriah." This phrase is certainly intended to draw our attention to David's sin (2 Sam. 11:1–5, 14–17). But it also seems significant that Matthew explicitly calls attention to Uriah the Hittite, a model of the man whose behavior surpasses what the law requires. Though not an Israelite, Uriah served Israel devotedly, even refusing to sleep in his own bed while the men with whom he served were at war (2 Sam. 11:11–13). Ironically, Uriah might have lived had he not chosen to go beyond the demands of the law.

The Character of St. Joseph

These themes illustrate how Matthew conveys the message that the Old Testament tells us primarily about the life of Christ. But where the Gospel according to Luke shows us that all of salvation history up to that point was a preparation for Mary's agreement to God's plan, Matthew's genealogy may be seen as culminating in the actions of St. Joseph.

In many ways, Joseph is the main human actor in Matthew's presentation of the Nativity of Christ. So while Luke narrates most of these events through the experiences of the Theotokos, Matthew places the emphasis on Joseph. Moreover, Joseph's actions bring together some of themes found in the genealogy, and thereby underscore the continuity between the Old and New Testaments.

First, Joseph is a model of the person who both honors the law and goes beyond its requirements. "Being a just man," he did not want to make Mary a public example when he learned that she was with child (Matt. 1:19). This impulse to mercy reflected well on the man who would raise the One who constantly reminded his listeners that the law was not meant to preclude mercy. Indeed, Joseph's actions serve as a prelude to all the occasions when Christ himself went beyond justice and showed mercy. Matthew subtly underscores this point when he emphasizes Old Testament figures like Uriah, whose commitment to justice was inseparable from their love of mercy.

Second, Matthew presents Joseph as a kind of early missionary to the Gentiles. Joseph takes his wife and child to Egypt. It is also possible that he met and spoke with the Magi, although the text only mentions Christ and Mary (Matt. 2:11). Again, Matthew prefigures this point by emphasizing various Gentile ancestors of Christ.

Third, the contrast between Joseph and Herod expresses a longstanding Old Testament theme—the contrast between faithful and rebellious Israel. A poor carpenter who flees to Egypt is the one who not only fulfills justice and mercy in a small way, but also is honored with the privilege of raising the Messiah. In contrast, the official king of Israel is a usurper who tries to kill the Messiah (Matt. 2:13–23).

The Mission of Israel

Finally, all of these passages show that, in one sense, the mission of Israel was fulfilled in Joseph. Since Matthew makes it clear that the story of the Old Testament is the story of the beginning of Jesus Christ, we may regard Matthew's emphasis on Joseph as indicating that he sees in Joseph a recapitulation of the story of faithful Israel. Thus, like Abraham, Joseph has a child by a woman who should not have been able to bear a son (Gen. 18:10–15, Matt. 1:18–20). Like Jacob's son Joseph, he goes down to Egypt (Gen. 37:25–30, Matt. 2:14). Like Moses' parents, he saves a child from a murderous king (Ex. 2:1–10, Matt. 2:13–15). And like Moses, he leads Mary and the child back to the Promised Land (Ex. 13:17—15:21; 34:1–12; Matt. 2:19–23).

In taking these actions, Joseph fulfills the mission of Israel not only in type, but also in fact. The mission of Israel was always to prepare the way for the Light to the Nations to come into the world. In the process, both the nation and individual men's hearts were many times divided between faithfulness and rebellion. But in the end, Joseph fulfilled the mission by protecting his wife's child and safeguarding for us the One who would save the world.

Unlike Mary, Joseph did not live to be a bridge between the time before and the time after the Resurrection. Like John the Baptist, he fulfilled his part in the story of Redemption and died before seeing its completion. As the Epistle to the Hebrews says, "And all these, having obtained a good testimony through faith, did not receive the promise" (Heb. 11:39).

Fulfillment in Christ

As we have seen, Matthew's genealogy gives us clues to how to read the Nativity story. In turn, both the genealogy and the Nativity story give us our first glimpse of several other major themes in Matthew's Gospel. First, they tell us that Christ is the new beginning. Second, they signal to us that we are reading the final story of conflict between faithful and rebellious Israel. Third, they remind us that Christ has come as the fulfillment of the law. And fourth, they remind us that the law was never meant to preclude mercy.

As it introduces these themes, the first chapter of Matthew's Gospel also reminds us that these themes are not new. They were all present in the history of Israel for those who had eyes to see them. From the time of Abraham to the time of Joseph, there were righteous men and women who saw them and put them into practice. They were part of the story of Israel from the moment the Lord chose Abraham until the time of Christ's birth. Through his Incarnation, life, teaching, crucifixion, and Resurrection, Christ fulfills them and brings them to completion. He then entrusts them to his apostles, so that what their fathers told in the house, they can proclaim from the rooftops to all the nations.

Salvation History in Brief

This Christmas, millions of Christians will go to church and hear the opening passages of Matthew's Gospel read. For many, this reading may be just one more nostalgic tradition of the season. For others, the genealogy in particular may be only a tedious part to wade through.

But the proclamation of this genealogy is not just a nice tradition of the holiday season. Nor is it simply a lengthy reminder that Christ was born of the line of David. Rather, in this reading, we have a poetic recitation that gives us both the Old and New Testaments in brief. Moreover, it reminds us that, in an important sense, the Two Testaments are not two stories. Rather, all the history of our salvation is the story of Jesus Christ. The story of the Nativity shows us that the Old Testament is first and foremost the story of "the beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ." •

Jacob Affolter is a lecturer in applied ethics in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Kentucky. He holds a Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of California at Riverside. He attends an Eastern Orthodox parish in Lexington, Kentucky. Questions and comments are welcome and can be addressed to Dr. Affolter at jaffo001@ucr.edu.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor