Catharsis? Caritas!

Thomas Howard on the Crucial Limits of Art's Power to Transform

In the mid-1960s, when my wife and I lived in New York, I used to pop in to Lincoln Center to take in bits and pieces of the New York Film Festival. It was all terribly heady. One wanted to be at the cutting edge. Au courant, so to speak. (I was young.)

The then-prominent names among the directors were mostly foreign: Buñuel, Renoir, Truffaut, Bergman, Fellini, Antonioni; a lot of the films were black-and-white. One didn't really think of the festival as mere entertainment. It was serious stuff, one told oneself. And indeed it was, from a given point of view. The films constituted a keen index, as it were, of modern sensibility.

My most distinct memory of these occasions is of the cinema buffs' remarks as they tottered, all agog, back up the aisle and left the theatre. Great rhapsodic breathings. Gasps of incredulity. There's catharsis for you! Now I know what Aristotle meant. Heavy.

It all started a train of thought in me that goes on until this day. And I speak as one whose livelihood for over fifty years has been the teaching of belles lettres. The concerns in these two fields, literature (in my case, the teaching of English literature) and cinema, are virtually synonymous. Literature, film, drama, music, dance, painting, sculpture, architecture: these would constitute what we commonly call "the arts," and would themselves bespeak our awareness of the significance that seems to arch over our mortal affairs, and the immemorial human effort to find concrete shape for that awareness. Dogs don't write poems. Eagles don't come up with new choreography. Dugongs don't create operas. Such attempts seem to belong to our species alone.

And somehow such activities seem to lie very close to the center of human consciousness and aspiration—so close, in fact, that finding the exact threshold between the arts and religion is not always an easy undertaking, since both evince this rum and dogged awareness that won't leave us mortals alone. I am speaking, of course, of imagination, which insists on finding a palpable shape (incarnation, shall we say?) for its experience of existence, whereas ratiocination seeks to get things articulated in discursive, propositional terms. (The question of the shape taken by Reformed theology and spirituality, as distinct from the ancient Orthodox and Catholic outlook, looms at this point . . .)

Cleansed Sensibility

As I overheard the remarks on every side as we all left the theatre after those evenings, a piquant question began to suggest itself to me—piquant, since I was preparing for a career in teaching belles lettres, and might myself be called upon to reply to some student's views on a question I am about to raise in the following lines.

The word that stuck in my mind was catharsis. Rightly understood, of course, this refers to a cleansing, or purgation. Aristotle speaks of this.

So: a cleansing or purging of what, exactly?

If we mooted the question at, say, a round table, the participants being experts from the various arts and (perhaps more important) critics and philosophers of aesthetics whose particular concern was to locate the phenomenon of art among the truly serious human enterprises, we would find ourselves regaled with several points of view.

Perhaps the matter of sensibility would arise early on. But what a can of worms! How, for example, are we to urge that to love Bach's Goldberg Variations bespeaks a higher sensibility than to love the big band swing music of the l930s? What we'd get would be a shouting match, with sociology and politics quickly commandeering center stage.

Do you mean to attach a pecking order of taste here, with Bach higher than swing? Come. That's just la-dee-da. The highbrows versus the unwashed proletariat, eh? Us ordinary folks versus some elite is it? And who would wish to find himself defending quite such a division of things?

The same uproar would bedevil any possible discussion in this realm. Are Vermeer and Caravaggio "better" than what one sees in local art fairs? Is Architectural Digest better than Beautiful Homes? Are the waltz and foxtrot better than current "dance" forms? Is T. S. Eliot better than my verses here? Is Jane Austen better than Robert Ludlum? What a donnybrook.

We have lurched into very delicate precincts here. Obviously, we are talking about discrimination. The word has been throttled down to mere politics and sociology in our own time, but its more ancient usage, meaning the capacity to see, and to judge, a scale of values from better to worse, would be at work in the present discussion. But again, "better" and "worse" have themselves been ruled out of court in our time, in everything from taste to behavior to morals to values. The egalitarian notion presides.

Cleansed from Sin

But I have something fundamental in mind. Catharsis ultimately suggests the cleansing that will make me a better man. Schooled at the feet of Sophocles, Phidias, Orlando Gibbons, Shakespeare, Leonardo, Mozart, and Balanchine, surely I will, if I am operating on more than two watts, become a more whole man? Finer values. Breadth of sympathy. Acuity of taste. Chastened -preferences.

Yes. All of that. But now I must put my Christian cards on the table. Will any such schooling make me a better man? There's the rub. Those last four phrases in the above paragraph certainly suggest qualities that seem to mark the civilized man—no doubt the man we would all like to know—nay, to be. Isn't it axiomatic that such marks distinguish me from the oafs and churls?

Well, perhaps, in a way. But something needs to be said on the point. We must press the thing further than civility, gentility, and taste, all of which, in their order, may be prized. But who is the good man?

Alas. Without canvassing the faculties of English departments in great universities whom I have known, I need go no further than my own inner man. Alas again. No smallest tincture of vanity, irascibility, humbug, venality, cravenness, disdain, or niggardliness has been even slightly touched, much less expunged, in me simply because I love Beowulf, King Lear, Mozart, and Vermeer.

The joker in the pack is not faulty taste, or ignorance of "the best that has been thought and said" in the world. Two cheers for Matthew Arnold, Henry James, and the critics. But they leave me where I was. The interior skirmish—the war, in a word—for me remains what it was.

The joker—one hesitates to be labeled a fundamentalist fanatic—is sin. The ancient curse. The thing that has beleaguered every man ever born to woman (and before: both Adam and Eve "fell"—not into bad taste, but into sin). Pride. Rebellion against the Most High. Iniquity. Guilt. All of the old, weary, shopworn tags.

We fundamentalists used to sing "What can wash away my sin? / Nothing but the Blood of Jesus." Oh dear. So proletarian. So Salvation Army. So tacky Sunday-night-upstairs-chapel.

No. So ancient, so Orthodox, so Catholic, so Reformation, so massively universal. The wine in the chalice: that, being the Blood of Jesus, alone can wash away my sin.

Can the Arts Produce Caritas?

But how to introduce this embarrassing note into any serious discussion of aesthetics? Probably it can't, and shouldn't, be done. It's the wrong forum. But of course, every idea, every contribution, every sentence even, in such a discussion, skirts the final issue—namely, what sort of men do we want to be? Or, what is better? What is the desideratum—for the Regius Professor of Classics and for the tinker with his cart and for the farmer in the dell? Finer sensibilities? Well, that's not to be scoffed at. But what will make them all "better" men?

Surely it is, in the end, mere charity. Caritas. The greatest of these. Purity of heart. Love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, meekness, self-control, faith. Though I speak with the tongues of men or of angels. . . . Or so would urge St. Paul—not, we might object, one of the panel at the Round Table. But is that a remark -touching St. Paul, or the Round Table? The good saint is merely an apostle, however. What remarks on the topic might we get from the Second Person of the Most Holy Trinity, who was incarnate by the Holy Ghost of the Virgin Mary, and was made man?

Now you are swamping us with mere rhetoric. Revivalism. This is tendentious. Uncouth, really.

But as I left the theatre on those nights, I wondered which of us in the audience would, say, refrain from bedding down our current favorite or some chance encounter on Bleecker Street? Or would offer help to some dribbling derelict in Times Square? Or have the courage to demur in the presence of profanity? Or refrain from striking back at an insult? Or hold our tongue when calumny is being visited on someone whom we dislike intensely? Will Bunuel help? Truffaut? Fellini? Or, let's face it, Bach or Shakespeare?

Protected Spectators

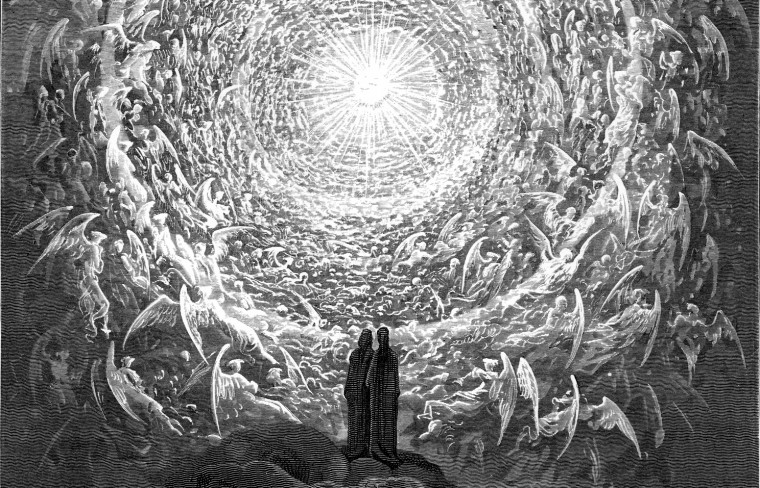

One further point has occurred to me over the years as I have mulled over such questions. I have wondered whether the claim that the arts might make us actually better (more pure in heart, more righteous) people might be stopped in its tracks by recalling that, with every one of the arts, we are spectators. We are sitting in our armchair, or across the footlights, protected. We are watching King Lear in agony on the heath. We are reading about evil and hell in Milton, or about descending to the bottom of the Inferno, and thence up Mt. Purgatory and on into Paradise, with Dante. We gaze at Van Eyck's "Adoration of the Mystic Lamb" in Ghent.

But in no case are we actually undergoing the experience. Oh, indeed, we may weep great tears or gasp rhapsodically over the splendors of the music or poetry, but the tears we shed over Lear ("'Her voice was ever soft . . .'") are nothing next to the tears we might shed over our own dead daughter. From the Christian point of view, suffering—and suffering alone?—seems to constitute the syllabus for us here in this mortal coil.

I take "the arts" seriously. The teaching of prose, poetry, and drama has been my livelihood. But I would be chasing an ignis fatuus were I to attribute to them anything that is actually salvific. Surely the Paschal Mystery alone is to be sought in that connection.

Thomas Howard taught for many years at St. John's Seminary College, the Roman Catholic seminary of the archdiocese of Boston. Among his many works are the books Christ the Tiger, Evangelical Is Not Enough, Lead Kindly Light, On Being Catholic, and The Secret of New York Revealed, and a videotape series of 13 lectures on "The Treasures of Catholicism" (all from Ignatius Press).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor